Читать книгу Cloris - Cloris Leachman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

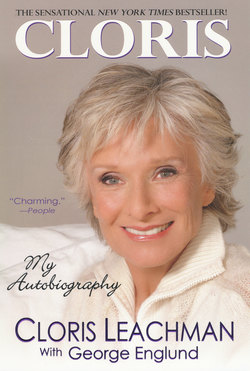

Autobiography

ОглавлениеI had to smile. Writing your autobiography is something you do in contemplation, isn’t that so? It’s a look back at the traffic of your life, the places you’ve been, the people you’ve known and loved. But I can’t get out of the traffic of my life today.

Recently, I won my ninth Emmy (the most ever earned by an actor), and I became a great-grandmother. In the last six months, I’ve made four films: The Women, with Annette Bening, Meg Ryan, and Bette Midler; American Cowslip, with Peter Falk and Val Kilmer; New York, I Love You, with Eli Wallach and many others; and a Hallmark Theater film. I’ve also traveled to New York, Rome, Cabo San Lucas, and Tempe, Arizona; had to cancel a cruise from India to Italy; been touring my one-woman show; celebrated my eighty-second birthday; and, oh yeah, been on Dancing with the Stars. I’ll come back to that.

That’s a life with some real bang and smash in it, but you know what? I like it this way; I like life to be exciting. And actually, in the middle of all that’s been going on, I did begin to write my autobiography. I really wanted to get it right, and I started off determined. I picked a chair, sat in it, with a pen and a pad, and it was “move over, Shakespeare” time.

Then, like autumn leaves, thoughts began to fall on me; they touched my soul. Emotions streamed through me: hilarity, tenderness, amazement, then sadness. It’s too late, a voice inside me said. It’s too late to collect the little girls who were you and herd them into the tale of your youth. It’s too late to walk again through those febrile high school years, when you were holding three jobs and studying piano and dance all at the same time.

It’s too late to recall the roles you played; the stars, the comedians, tragedians, and vaudevillians you shared the stage with; the costume and make-up men and women you became so fond of; the playwrights and presidents you dined with. It’s too late to remember the early morning when Adam, your fair firstborn, came out of you and entered the world, and the unbearable hour when Bryan, your handsome second son, left the world.

Then a different voice spoke. It’s too soon, too soon to peer into yesterday, when your eyes are so expectantly fixed on tomorrow, when your children, grandchildren, and great-grandchild are growing up around you. It’s too soon to look back on your life, as if you’re nearing the end of it.

Sitting there, utterly still, tears slipped from my eyes as the times of my life gathered around me. I thought, What’s the best way to tell the story of your life? Do you begin at the beginning and follow the calendar to where you are now? Or would it be better to begin with a particular event, the day you were married or the day you won the Oscar or the day your son died, and work backward and forward from there?

Or you could sum it all up in numbers. I was one of three daughters; I gave birth to five children; I have one Oscar, nine Emmys, and sixty-eight other awards. I have seven grandchildren, I am eighty-two years old, I’ve been on six of the seven continents, and if they produce a television series on McMurdo Sound, I might soon visit Antarctica.

Enough of this inner dialogue, I thought. I’m just going to write it. I’ll start easy. I’ll tell about what I’ve learned and what I still don’t know. Right away that brought up something big, I still don’t know if there’s a God. From the unkindness and slaughter in the world, it’s hard to believe He’s the good guy portrayed in the paintings. I tend not to believe in Him or Her. And yet, sometimes when my grandchildren and I are together—out with the dogs on a sunny afternoon or in my living room, playing the piano—such joy surrounds us, such tender emotions swell, that I feel we’re not alone, that some dear, loving presence is there, too.

Right here, at the beginning, I want to say some things about myself I know to be true. I’ve lived my life; I haven’t trotted alongside it. I’ve opened the doors of opportunity wherever I’ve seen them. I’ve walked into discoveries and dreams, disappointments and death. I bear the scars of not having obeyed rules made by others, and I wear the deep satisfaction of knowing I never bent to conventions I didn’t believe in.

I never wanted to conform. I haven’t conformed. I’ve tried, but I couldn’t. I’ve never put a label on myself. I find it distasteful that people put labels on other people and say that’s who they are, that one thing. When I was forty-six, people said I was in middle age. I shrugged off that designation. I didn’t want to be lumped into a group. Here’s something I said in an interview with Playgirl magazine in 1972.

I knew from the very beginning that I didn’t belong in Iowa. When I went into town for my first piano lesson, I took a streetcar to the teacher’s studio. It was the most staggering cultural shock of my life. There were all those gray people, the nine-to-fivers, sitting in a stupor. Right then I determined with every fiber in my being that I would never be ground down into a gray person. I’m not going to adopt any wholesale anything. No organized religion, no organized anything. I have never known depression. Depression means there is no way out. I have been deeply saddened, heartbroken, hysterical, exhausted. But I never felt there was no way out. I’ll make a door.

Having written this much, I decided it would be wrong to write my autobiography in chapters, because I didn’t live my life in chapters. The long walk I’ve taken wasn’t divided into tidy sections. It came in arcs and rainbows, sprints and marathons, clouds and clear places.

Something else came into focus with razor sharpness, that everything I’m going to write about, every minor event, every major accomplishment, took place in the past. As I absorb that thought, I see I am in a softly lit world. My mother’s voice speaks behind me…Music from my twenties starts over there…In the middle distance, a piano solo begins, Beethoven’s “Für Elise.” Emotions rise in me, because piano music has filled my life since I was seven years old…Now an odor, alien and foreign, oh yes, gunpowder, from when I took that course in marksmanship at the armory to get Daddy’s attention.

There I am with Mama, carrying buckets of water from the well because we don’t have enough water at home for wash day…Laughter erupts. There I am as Nurse Diesel in High Anxiety, with those conical breasts…and, oh, remember, there I am at nineteen, holding the trophy I won as Miss Chicago.

I could start my book with any of these memories…but I think I won’t. I think I’ll start where I didn’t think I would start, at the beginning.

In April 1926, Cloris and Buck Leachman were about to have their first child. Buck was in the early stages of building his business, the Leachman Lumber Company, and there was no extra money. Nevertheless, when their first offspring was about to enter the world, they wanted to make a proud announcement. Daddy decided he’d send a telegram. That was a huge notion, because telegrams were costly. You paid by the word. Mama really didn’t think they should go that far, but Daddy was heady and reckless. He went out the door like a riverboat gambler and sent a telegram announcement to his sister, who lived in another part of the state. GIRL was the entire message. That fanfare played me onto the stage of life.

Our house sat in an area called Lone Tree, three miles outside the Des Moines city limits, on Route 6, a two-lane highway. There were places for other houses, but only a few had been built, so there was a lot of space in which I could roam. We had a huge vegetable garden and some animals—a pig, sheep, ducks, and geese.

Mama had an inventive streak, sometimes we made our own soap out of bacon grease. We didn’t have to. Mama just wanted to experiment. And, my younger sisters, Mary and Claiborne, and I were always wearing strange-looking dresses because Mama made them from Vogue patterns, and the fashions hadn’t reached the Midwest yet.

Some of the ways Mama and Daddy interacted with each other sculpted the way I see the world. Memories of how they were together come back to me now with great clarity. There was never a cross word between them. Somewhere, sometime they had worked out a system of dealing with their differences. When they felt an argument was imminent, they would sit down, and Daddy would stay silent while Mama reenacted the incident, playing both their roles. She would begin by stating Daddy’s position in her version of his masculine voice. Then she would recite her view in her own voice. Then she’d respond in his voice to what she’d said in her voice. Somehow things got worked out in the end. Maybe Daddy was sedated by the process.

On a lighter note, Mama and Daddy would sometimes argue about how a word was pronounced, and they had a system to handle that. They’d each put up ten dollars, and then Mama would go to the dictionary and read out loud which syllable of the word was to be emphasized. The loser paid up.

The family sat down at the same time every night for dinner, and each of the girls had a dinnertime job. Mine was to set the table. I remember how I did it one particular night. I put a little green lettuce cup on each of our five plates, then added half a pear. I put some cottage cheese next to the pear and an English walnut on top. To finish, as Mama had taught me, I put the forks to the left and the knives and spoons to the right of the plates.

I hated to get my hands dirty in the kitchen, so I was happy to set the table, which I considered the most sanitary way to be helpful. I remember thinking that when I got married, I’d wear rubber gloves so I’d never be touched by anything. Want to know about crazy, want to know about upside-down thinking? My other job was to clean the bathroom. I thought that was a nice, tidy thing to do.

Daddy and my two sisters did the dishes after dinner, and I practiced the piano. I felt guilty about not helping, but I just couldn’t put my hands in dishwater and there were plenty of wipers, and we had very little water, anyway, so, okay, Cloris will practice the piano.

In the winter we’d go from the freezing cold outside to the freezing cold inside our house. Daddy would put the coal in the furnace and get it going, and Mama would start getting dinner ready. Usually she had put something on ‘pre-bake’ in the morning and she heat it to the finish when we got home. If we’d all been out in the car, we’d be singing all the way home. Mama would sing with us, but Daddy didn’t. Daddy didn’t nurture his relationship with us, we had no kind of physical contact with him. There were no hugs or cheek kisses or pats on the back. He’d get up in the morning, shave, take a bath, put on his Mennen aftershave lotion, comb his hair, part it, and go to work in his black, four-door Buick. When he came home, he’d say hello to all of us, then sit down and read his newspaper.

Generally, I saw Daddy at the end of the day. After I’d finished my lessons, I’d take the streetcar out to the lumber company, and we’d drive home from there. It sticks in my mind that when Daddy got out of the car, one shoulder was always lower than the other. I don’t think it was due to an injury. Maybe all he needed was to go to the chiropractor. I just watched him. I didn’t know my father.

When I was a little girl, I didn’t know anything about Mama and Daddy’s courtship, but one time when Mary and Claiborne and I were up in our attic, we saw this little valise, which we hadn’t noticed before. We opened it, inside there was a beautiful dark blue dress. I asked Mama about it, and she said that she got married to Daddy in that dress. Apparently, she’d been pregnant with me at the time, but I didn’t learn that until years later.

I think I was twelve when I looked through that valise again. I felt something underneath the photographs and jackets and pulled it out. It was a beautiful silver tray, and on it was inscribed: NOVEMBER TWELFTH, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND TWENTY-FIVE. ON THIS DATE CLORIS WALLACE MARRIED PAUL WHITE. Oh my god, I thought. My mother was married to someone else before Daddy, and she never told me. I’m not Daddy’s daughter. I’m Paul White’s daughter. That was an unmanageable drama, and I was crying when I spoke to Mama about it.

“Who am I related to?” I asked. “Who do I belong to?”

Mama told me right away that I was Daddy’s daughter. She said that when she was nineteen and at Drake University, she’d gotten married to a darling guy who was president of his fraternity. They’d lived in an apartment, but then, suddenly, they’d had to move. Mama hadn’t known why, but she’d thought that the problem was financial. Right after that, her new husband disappeared. And right after that, movers came and took their furniture away. Mama’s father brought her home and got her a divorce.

Daddy and Mama met when she went back to Drake. Daddy began his college career there, but his father contracted what we now call Alzheimer’s, so Daddy had to quit college and support the family. Right after he and Mama got married, Mama was in a very unhappy state because Grandma Leachman was totally against the marriage. She said that Buck had married a divorced woman. That was close to being a capital sin in Des Moines, Iowa, in those days, so Mama was deeply concerned and deeply hurt. But, crazily, it turned out that Grandma Leachman came to love Mama and became closer to her than anyone else in Daddy’s family.

Mama was completely different from Daddy. She’d read a story to us, and her voice would be so interesting: she would become all the characters. She’d make them come alive for us. Mama always made dinnertime fun. She’d ask, “What was the worst thing that happened to you today?” Then we would all recount whatever terrible thing we could think of that had happened. Then she’d say, “What was the best thing that happened today?” It made us think. We’d all take a moment to come up with our answers.

Every day, when I came home from school, Mama would tell me something to let me know she had been thinking of me. She would advise me to do this or that. And I’d think to myself, Oh my goodness. She’s been thinking of me. It was usually a good little idea, one that eventually helped in some way to build my career.

Mama was funny, too. She liked to tell this story about herself.

We always had a charge account at Younkers, the big department store in Des Moines. Mama went there rarely, because it meant taking the bus, and when she got there, she couldn’t buy anything, because what money we did have would go back into the business. Anyway, one day she found herself there, walking through the millinery section, and she noticed a little pillbox hat with a veil on a stand, a pretty little thing.

The saleswoman said, “How are you today, Mrs. Leachman?”

“Oh, fine. Thank you.”

“Isn’t that a darling little hat?”

“Oh yes. It caught my eye.”

“Would you like to try it on?” Noting the hesitation in Mama’s face, the saleswoman added, “Oh, come on. Let’s just try it.”

So Mama sat down on a little stool before three mirrors, one in front and one on each side, but her head didn’t come up high enough for her to get a good look. In those days you didn’t handle the hats; the salesladies did. So, the saleswoman picked up the hat ever so carefully and brought it over to Mama. Then she handed Mama the little hand mirror so Mama could see the hat from all angles.

She asked Mama, “What do you think? It’s certainly a pretty little hat, isn’t it?”

Mama said, “Well, yes, it is a very pretty little hat, but my face is so round.”

The saleswoman said, “I didn’t notice that so much, Mrs. Leachman, but you don’t have any neck.”

Everybody loved Mama. She provided laughter and good food, and she was never judgmental and always inventive. When I was little and Mama’s sister Lucia would visit, she and Mama would give me a bath and put my pajamas on and make a lip-smacking homemade noodle soup. Mama made her own noodles and hung them to dry on the towel rack. Then, when she needed them for dinner, she’d cut them up.

Another of Mama’s stories goes like this: Each year a major contractor invited all the lumber dealers from different parts of the state to go hunting in Arkansas. Daddy went every year. It was the high point of his life. He’d bring home pheasant and duck and quail. Mama would have a series of dinner parties and serve these special dishes. It was a big event, she even had little wooden ducks hung on strings over the center of the table.

Even though I was a little girl in the middle of the country, I knew there were very big things ahead for me. In a way, I came from privilege, and by that I don’t mean money so much. We were privileged because we spoke well. We didn’t say “ain’t.” At school the teacher would ask me to read in front of the class. It wasn’t big-time show business, but the little cues around me told me I could do things well. My behavior didn’t come out of discipline, it came out of enjoyment. Everyone took an interest in me, and I enjoyed the idea of excellence.

Daddy was the trunk of our family tree. We were warm and safe because of him. We never went hungry because of Daddy’s care. I don’t like to keep mentioning the same point, but even now when I think about him, he’s always at a distance. I guess the most accurate word to describe him is remote. Mama was so different. She was as close to Mary, Claiborne, and me as a mother could possibly be, always embroidering our lives.