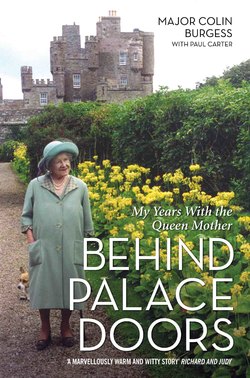

Читать книгу Behind Palace Doors - My Service as the Queen Mother's Equerry - Colin Burgess - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A SLEEPING LUNCH

ОглавлениеThe summer of 1995 had been glorious. There had been constant blazing sunshine since Wimbledon and this particular day was no different. The Queen Mother was enjoying lunch in the garden of Clarence House with her ‘home team’: her treasurer, Sir Ralph Anstruther; her private secretary, Sir Alastair Aird; her senior lady-in-waiting, Dame Frances Campbell-Preston, and me. By ‘home team’ I mean her top staff, the people she relied on day in and day out to get things done and make her life as comfortable as possible. So there we sat – I had no reason to suspect this day would be any different from ones that had gone before, but I was wrong. We had finished the main part of the meal which had consisted of an egg starter followed by chicken and potatoes, mashed potatoes because they were the Queen Mum’s favourite. The wine, a full-bodied claret which wasn’t really conducive to a hot summer’s day, had been passed round and a few bottles drunk, and conversation dipped in and out of subjects as diverse as World War II and the latest episode of EastEnders. About five minutes after we had finished our main course, though, I began to notice that the chatter was slowing down, rather like a record meanders to a gradual stop when you turn the speed off. Then I saw Ralph nodding off and I just thought, oh well, never mind. He had done this before and age was catching up with him, plus we weren’t entertaining guests or anything so it didn’t really matter. But no sooner had he started snoring than the Queen Mother closed her eyes and she was asleep. This was a first for me. I had never seen the Queen Mother fall asleep during any meal. I turned to Alastair to ask his advice because I really didn’t know what to do. I mean, what is the correct procedure for waking up a member of royalty who has nodded off during a meal? Did any exist? Alastair was unable to answer me because he, too, had fallen asleep. The next thing I heard was a gentle thud on the dining table as Dame Frances’s head hit it and she had gone as well. The four of them sat there absolutely out of it with Alastair gently buzzing as well and the Queen Mother’s head slumped forward.

I sat there for five minutes, which became ten, and all the while I was thinking, someone is going to wake up any minute, but they didn’t. All in all, I sat for a full thirty-five minutes not knowing what the hell to do. At one point, I actually got up to stretch my legs and go for a bit of a walk round before coming back to sit down again among the sleeping throng. The merest hint of an idea hit me: I imagined what it would be like to draw comedy moustaches on their faces, just as Steve Harmison did recently to Freddie Flintoff during the Ashes celebrations! The whole situation was bonkers. I was banking on a waiter appearing to clear the plates. But he wouldn’t appear until the Queen Mother rang the bell, and she wasn’t going to do that because she was gently contemplating the events of the day behind closed eyes. Eventually, it got to the point where I felt something had got to happen otherwise I would be spending the rest of the day just sitting there. So I thought, damn it, and I rang the bell that summoned the servants in a desperate attempt to rouse them. Now this was a major breach of protocol. Nobody can ring the bell unless invited to by the Queen Mother. And blimey, as soon as it rang they all sat up and just carried on from where they had left off with Ralph exclaiming, ‘And of course the Italians simply gave in once the Germans had gone.’

Alastair added, ‘You know I just don’t know, anyway…’

And off they all went, chattering away as though the whole of the previous thirty-five minutes had never happened.

I tried not to look too surprised and thinking to myself that, in all the time I had been working at Clarence House, this was possibly the most bizarre moment I had witnessed. But in the end nothing really surprised me about working in a royal household because I had met some of the most eccentric, entertaining and charming people that I had ever met in my life and the opportunity arose completely by chance.

I was about to leave the Army, in 1994, at the age of twenty-six, having spent three years in the Irish Guards. After completing the one-year Army pilots’ course, I had then flown helicopters in the UK, Northern Ireland and, finally, in Australia. I felt I needed a fresh challenge and an opportunity came up to fly with the Air Ambulance in Sydney, a challenge that I was looking forward to. But this was to pass me by with just one telephone call from my regimental adjutant. He asked if I would be interested in looking after the Queen Mother. This completely threw me. I asked him in what capacity would I be looking after her? I kept thinking: what does he mean ‘look after’? He told me the position was as the Queen Mother’s equerry. I had heard of an equerry but only in the old-fashioned sense of it deriving from the Latin eques, meaning knight or horseman. But the job had nothing to do with fillies and mares and stables. Instead, it involved being around the Queen Mother for the majority of the day as what you might call her fixer and organiser for the two years that each equerry held the post. The role itself didn’t really have a set job description, or any training as such. You couldn’t apply for it; you were invited to do it by the Army. I was a bit confused and mightily surprised. I wondered why the hell anybody would want me looking after the Queen Mother; it would be like putting Paul Gascoigne in charge of a brewery or something. I didn’t come from a wealthy background and, to paraphrase Tony Blair, I was just a regular kind of guy. Surely the job would go to someone of a much higher social standing than I had. Previous equerries had included such luminaries as Earl Spencer, Princess Diana’s father, and Captain Peter Townsend, who almost ended up marrying Princess Margaret. I then discovered that they had head-hunted two other people, both with double-barrelled surnames, and I was up against them for the job. I was sure I was only being put forward to make the process seem fairer; that is, to tick the right boxes in terms of giving everyone from each social bracket a fair whack. The other two were much more what I would term upper class in their manners; at least what I thought that was at the time. They were a bit stiff and a little aloof, things that to me seemed to be necessary requirements of the job and which therefore would make them far more suitable than I could ever be. I had a tendency to crack jokes and my experiences as a pilot, where you are left very much to make your own decisions, had made me less in-tune with the Army system, and had given me a healthy scepticism of unnecessary protocol. But I was invited to lunch with the Queen Mum’s treasurer Sir Ralph Anstruther at Pirbright Army Barracks in Surrey and I thought, well, I’ll give it my best shot and just be myself. If he didn’t like me, then it would be providence and I would simply continue with my plans to fly in Australia.

Sir Ralph, a seventy-two-year-old former Coldstream Guards Officer, was in charge of the Royal purse, which meant he oversaw the Queen Mother’s spending, and was feared by all the staff at Clarence House because he was a stickler for the rules and vigorously enforced them. I think it all stemmed from his time in the Second World War. He had fought in the Second Battalion that landed in Algiers in 1942. Some months later, in 1943, his company attacked an enemy stronghold north east of El Aroussa in Tunisia, nicknamed ‘Steamroller Farm’. As they approached in Churchill tanks, Anstruther and his men had to march the last mile towards the enemy on foot and exposed to intense enemy fire. It became obvious to him that the battalion needed cover and, despite being wounded, he refused any medical attention until his men were safely withdrawn. He achieved this with such skill and direction that there were no casualties and he personally shepherded the wounded back to safe ground to be treated. For this he won the Military Cross. But his heroism didn’t stop his commanding officer berating him from time to time for not having his tie done up properly or for having muddy shoes, and it was this attention to detail that he had somehow inherited from the Army and brought with him to the Royal Household which sometimes made the Old Etonian, who still called airports ‘aerodromes’, exude an air of crusty formality that made him seem horribly stiff and unapproachable to other members of staff. But actually, I liked him. He was ‘old school’ Army, a dying breed nowadays, and wanted everything to be done properly. That’s why he went on constantly about shiny shoes and starched collars and having the proper clips and pins. Staff would live in fear of his daily inspections. Even senior staff, including the private secretary and the equerry, were not spared the eagle eyes of Sir Ralph and we would all subtly and almost subconsciously check ourselves over before he came into the room. But, to me, that was how you did things in the Army, so I didn’t mind so much. I just utilised the things I had picked up in Her Majesty’s Forces and made sure I always had polished shoes and wore the correct apparel for each occasion. One of the few times I did see Ralph drop his guard was during a State banquet, when a young lady waltzed passed him and he turned to me and said, ‘Look how high that girl’s dress is. You can almost see her crotch.’

I remember thinking, did he just say what I think he said? This went way beyond accepted protocol and certainly was not part of the list of things an equerry had to check out! It was akin to the first time you hear your father swear in front of you in the sense of it seeming rather surreal, and I couldn’t have been more surprised than if I had woken up with my face sewn to the carpet.

So there I was sitting across the table from this fairly frail old man, who was dressed immaculately and sported a neatly trimmed moustache, and the other two men up for the job who were either side of him. I thought to myself, they have smoothed themselves into position already and I have no chance. So I relaxed completely and, thinking the job was out of my grasp, I became chattier. About half an hour into the buffet lunch, Ralph discovered that I had an uncle who was in the Coldstream Guards, and that seemed to swing the whole interview my way. The other two candidates were suddenly left out in the cold. All we talked about for the rest of the meal was Ralph’s time in the Army and my uncle’s history. At some stage during the interview, my two rivals for the job left the table to get some pudding. As soon as they were out of earshot, Ralph turned to me and said, ‘Don’t think much of those two. They’re far too oily for me.’

I suddenly realised I had moved from rank outsider to front runner and sure enough, less than a week later, I got a call to go and have lunch with the Queen Mother at Clarence House. She wanted to assess my suitability. I was told to turn up wearing a suit and a detachable, starched collar.

I had eaten with royalty before. It was at Windsor Castle where the Royals had converged for their annual winter break – they moved to Sandringham after the fire – and I was invited there as an Officer of the Guards for dinner in 1987 and had sat between Marina Ogilvy and Princess Diana. It was an amazing evening. Diana was lovely, really lovely, and we talked about life, relationships and a whole host of other fairly innocent topics. She really did come across as this very pleasant and extremely charming young girl, and if she and Charles where having problems at that stage, then she hid them very well. The experience was enjoyable, if a little daunting.

Fast forward seven years and in the summer of 1994, it appeared that I was faced with an even more daunting prospect: a mid-week lunch with the Queen Mother who was then the most senior Royal on the planet. I arrived at her London home and was led through rooms containing porcelain Limoges eggs, amazing paintings that were mainly by British artists of the early to mid-twentieth century, antique grandfather clocks and all sorts of grand objects that made you think you were walking through an old museum; but it wasn’t a museum, it was a working house where every morning a clock-winder would come round and wind up all the clocks. I fell instantly in love with the heritage of it all; it was a house that seemed lived in. Critics have said the Queen Mother allowed Clarence House to fall into disrepair in her later years. I disagree. I would compare it to a fine wine in that the more you leave it the more character it seems to develop. It was wonderful, even down to wearing those starched collars which gave me a terrible neck rash for the first year of my employment there, until I discovered I should have worn them one size too big for comfort. With the strict dress code and the antique furniture, it did very much resemble an Edwardian household and this was in some ways a tribute to its history. Historically, it has been home to some of the world’s most prestigious aristocrats. The three-storey mansion was built by John Nash between 1825 and 1827 for Prince William Henry, Duke of Clarence. The Prince lived there as King William IV from 1830 until 1837, and it was the London home of the Queen Mother from 1953 until her death. In 1942, it saw war service when it was made available for the use of the War Organisation of the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem where 200 members of staff of the Foreign Relations Department kept contact with British prisoners-of-war abroad and ran the Red Cross Postal Message Scheme. As I walked through the house, soaking up the atmosphere and the history of the place, I just thought, wow!

As I lunched with the Queen Mother in these fantastic surroundings, I wondered how many people got the chance to have even ten minutes with her, never mind enjoy a full and rather personal meal. I kept experiencing moments of sheer exhilaration during which I would be thinking, if only my family could see me now.

The Queen Mother broke the ice by saying to me: ‘So, Colin, tell me a bit about yourself. Do you have a girlfriend?’

‘Erm, no, ma’am,’ I replied, thinking this was all a bit unusual.

I had expected a much more formal kick-off, but I suppose it was a great way of putting me at ease.

‘Oh, why not?’ she asked.

‘I’m just waiting for the right girl to come along,’ I said.

And she just left it at that, no follow-up question, nothing. However, she didn’t seem displeased. The job was, after all, only given to single men on account of the unsociable hours that included late duties, entertaining and other things. So to have a full-time girlfriend would not have been easy. I felt I had somehow passed the first test. In hindsight, of course, that is exactly what it was, a test. We then went on to another subject and in her own very informal and very chatty way she proceeded to extract all the information she needed while very subtly assessing my suitability for the position. Luckily, things seemed to be going in the right direction.

For the next two hours, we talked of my family, where I lived, my education and a whole host of other personal things such as where I liked to go on holiday, whether I had pets or not, which also seemed to be quite important to her, and I remember her being keen to talk about the fact that I had boxed when I was younger. She also steered the conversation towards horse racing which I knew she loved but which I knew very little about myself, so I told her that I had the odd flutter now and then, which was a bit of an exaggeration because I only betted on the Grand National and I even missed that some years.

At the end of the first course, she showed me a rather sinister-looking pointed pearl embedded in a bejewelled box on the table. From its underside were wires trailing to the edge of the table. This was the bell that she used to summon the servants. If you pressed the pointed pearl which was on the top of it, it would ring, summoning the butlers or whoever was needed at the time. She said, ‘Now, Colin, I call this the Borgia bell.’

I had no idea who the Borgias were, but she continued, ‘The Borgias were an Italian family who lived during the Middle Ages and were famous for bumping off their guests. They would invite people that they did not like for dinner and kill them in many different ways. The Borgia bell goes back to when this family had a bell with a spike on top, which you pressed to make it ring. They would invite their guests to hit the bell to make it sound, but these guests were unaware that the tip had been spiked with poison. When they hit it, it invariably punctured their skin and killed them.’

The Queen Mother recounted this story to me in gleeful detail and then smiled and said, ‘Now, Colin, would you care to press the Borgia bell and we shall have our next course.’

I gave it a good whack, and bloody hell it was painful. I thought, what if she’s trying to poison me! Luckily, I survived, and throughout my two years at her side she would often ask me to ring the Borgia bell. It was her little joke. It came up regularly. Over the later months, she would invite various people to press the bell. Occasionally it would be a noisy guest. The Queen Mother might not tell them the story but instead would look at me with lips upturned as they pressed and winced. I felt as if I had been invited into a conspiracy, albeit just for fun. It was wonderful.

The meal itself was unmemorable, in so much as it was quite simple: a sort of eggs Florentine for starters – those eggy starters were a favourite of hers – followed by meat with boiled potatoes and vegetables, and chocolate fondant for pudding. What was memorable was her fondness for red wine, particularly heavy clarets which she loved. We must have gone through a bottle and a half at that first meeting. I was later to discover that she was a devoted drinker. That’s not to say she was an alcoholic, far from it, it was just that she loved social drinking and of course her life was very social. She would have her first drink at noon, which would be a gin and Dubonnet – two parts Dubonnet to one part gin, a pretty potent mix. She rarely went a day without having at least one of these and getting the mix right was crucial. For official engagements, I would go ahead to the venue a few days before and instruct the waiting staff on the correct way to put the drink together. On occasion, I would have to take a bottle of Dubonnet along with me. It is not a standard drink these days.

The gin and Dubonnet would then be followed by red wine with her lunch and, very occasionally, a glass of port to end it.

Later, at the end of the day, we would approach what the Queen Mother referred to as ‘the magic hour’. The magic hour was 6.00 in the evening because this was the accepted time when one could have an evening drink and the Queen Mother would sometimes say to me ‘Colin, are we at the magic hour?’

I would then rather flamboyantly look at my watch, raise an eyebrow and say to her, ‘Yes, ma’am, I think it’s just about time,’ before popping off to mix her a Martini.

Mixing a Martini was a bit of an event in itself. It consisted of gin with a sensation of vermouth. I would fill a glass with ice before pouring in the gin. Then I would squeeze lemon rind all round the edge of the glass before twisting some of the lemon juice into the gin. The vermouth would be poured into the screwcap of the bottle and the contents held over the glass (the right way up so that it didn’t spill) so that some of the fumes from the vermouth would somehow miraculously waft into the gin and be absorbed into it. I would then pour the vermouth in the cap back into the bottle. After a couple of these, the Queen Mother would sit down to dinner and drink one or two glasses of pink champagne. This was always Veuve Clicquot, which she insisted on, and she would never have more than about two glasses, leaving the rest of the bottle to be collected and finished off by the staff backstairs. She stuck to this routine the whole time I was there.

I went away after my first meeting with the Queen Mother thinking, this is going to be quite a thing to get through, especially with the amount I would have to drink. I have never really been much of a drinker and anything more than a glass or two, particularly at lunchtimes, finishes me off. And I had also never been for an interview like that before. It was very chatty, but also quite subtle. In her own very informal way the Queen Mother had found out exactly what she needed to know about me. But in return, I was certain I had blown my chance because the whole thing just seemed a bit too relaxed. All this changed when, a week later, I got a call to say that I had got the job. All I could think was, well, I can always return to flying helicopters, but this job will never come round again. And so it began.

My predecessor as equerry was a young Australian chap called Edward Dawson-Daimer, who was the son of Lord Portarlington and also an Irish Guards officer, as all the Queen Mother’s equerries are. He loved all the schmoozing and meeting people and on my first day he told me, ‘This is a great place to meet eligible girls. They’re everywhere here at the Palace.’

Sure enough, he would organise the occasional drinks party at Clarence House where the only invitees seemed to be tall, blonde-haired and short-skirted personal assistants and secretaries from places like St James’s Palace and other royal households. In they would trot and he basically got the pick of them, not bad if you were into Sloaney pony types. So for the next three months this cross between Alfie and Austin Powers acted as my guide, as I was gradually introduced into my new role which started just before the Queen Mother’s birthday in August 1994.

I remember my first day quite vividly because a lunch was being held for the handover to a new commanding officer of the Black Watch, which the Queen Mother was endorsing. Whether I was still on a high at landing the job, I do not know, but what I do remember is sitting there eating, observing what was going on and drinking and drinking and drinking. I was encouraged to keep the guests company measure for measure and over the long afternoon this meant rather a lot of alcohol. I became quite the worse for wear.

At the end of October the handover took place and I was on my own.

There then followed a two-year rollercoaster ride of trips to important places of massive historical interest that, to this day, I would never have had the chance of seeing if I had not landed this dream role – I stayed at the Royal Lodge in Windsor Great Park, Sandringham, Balmoral, Birkhall, the Castle of Mey and Walmer Castle to name but a few places.

On my first day alone in the job, I was collared by a slightly stern member of the Queen Mary Knitting Guild, who said to me, ‘Who are you?’

I explained that I was Equerry to the Queen Mother and she said very disparagingly: ‘Well, you probably don’t understand what pressure is just doing lunches here and dinner parties there. I have to arrange thousands of knitting patterns a year and co-ordinate lots of ladies all round the country. The pressure of the whole thing you probably would not be able to understand.’

I had just spent the last few years flying helicopters with the Army, some of which was spent in Northern Ireland ferrying casualties to hospital. I remember standing there looking at her and thinking, what sort of world have I just walked into? I felt a sudden desire to get into an argument with her, but that would not have been the most auspicious of introductions to this life of duty.

Generally, life at Clarence House was very pleasant. There wasn’t much running around and there were few, if any, raised voices. It was all very relaxed. I was accepted into the Queen Mother’s inner circle – the treasurer, private secretary and the ladies-in-waiting – virtually straight away, which was important because this had not always been the case with previous equerries, and they ended up struggling to cope with the role and found themselves somewhat ostracised. For some barmy reason, one young chap took it upon himself to pick arguments with the Queen Mother, so that within a couple of months of being installed in the post he was told that there was an urgent need for him to return to his regiment for ‘operational’ reasons. He was fired, basically. But the whole point of the job was that no equerry was ever fired. If the Queen Mother found your face didn’t fit, you would be told your regiment needed you to take up a posting in Northern Ireland, or somewhere like that. These days it would probably have been Iraq. It was all done by nods and winks. If you upset the Queen Mother, there was a whole number of exciting reasons for returning to your unit, or being given an RTU, as it was known. One equerry narrowly escaped an RTU after being constantly late. The penny dropped after the Queen Mother got him an alarm clock as a Christmas present!

But I made sure I was never late by getting in at 9.45 every morning to start work at 10.00. It was fifteen minutes by motorbike to Clarence House from my one-bedroom flat in Stockwell, and on arriving I would be given tea and biscuits by an orderly before consulting the desk diary to see what needed to be done. For the next hour or so, I would be on the telephone organising the Queen Mother’s week and then it would be lunchtime. We would sit down to eat between 12.30 and 1.00 and this would last for a couple of hours, if I was lucky, and then there would be more phone calls to make and enquiries to follow up as a result of lunch before afternoon tea at 5.30 in the lady-in-waiting’s office.

These meetings were not compulsory, but they were vital in the sense that it was the only time the inner circle of equerry, treasurer, private secretary and lady-in-waiting could get together and have the sort of conversation that they wouldn’t normally have in the presence of the Queen Mother on topics such as newspaper reports and general staff gossip. If you missed these meetings, you could bet your life that the subject of the conversation would be you. It was at these get-togethers that Ralph would always ask me who I had booked in for lunch for the coming weeks and you could guarantee that if I named someone he wasn’t aware of, he would reply, ‘Do we know them?’

This could have been his catchphrase, but it wasn’t said in a snobbish way. It was a way of making connections and a way of making introductions easier when these guests arrived at Clarence House. Ralph would always want to know a person’s status or social background, so he could tell the Queen Mother in order for her to bring it up when she met them. It was a way of breaking the ice and making guests feel comfortable and at ease. It was another way of saying, can I have a background check on this person so that I can pass it on to the Queen Mother.

Following afternoon tea, I would generally fix the Queen Mother a drink before leaving. I very rarely stayed for dinner at Clarence House.

So I was learning the ropes and generally getting on well, when a few days after the handover, I almost came unstuck over the sticky problem of how one addressed other members of staff. My initial intuition was to treat the lower orders as subordinates and address them as such, much in the same way as I had learned in the Army. Thus an early encounter with one of the Queen Mother’s chauffeurs had me telling him, ‘Okay, the Queen Mum needs to leave at nine. Be here at eight forty-five prompt, ready to leave.’

To which he replied, ‘Well, not if you ask me like that.’

I was astounded. ‘What do you mean?’ I spluttered. ‘It’s your job.’

‘Well, not if you just tell me what to do it’s not.’

This was absurd. How the hell was I going to get the Queen Mother from A to B if the staff were going to ignore my orders? So I gave it to him straight: ‘You are the chauffeur, it’s your job. Be there fifteen minutes before departure to collect the Queen Mother.’

‘No!’ he replied.

I walked away in despair. Twenty minutes later, I was being ticked off by the private secretary over how I had spoken to the chauffeur. Alastair said, ‘Look, you can’t speak like that to the chauffeur; he is a very emotional person.’

‘But it’s his job,’ I pleaded.

‘I know it’s his job,’ he said, ‘but you just have to approach it in a very nice kind of conversational way.’

It ended up with me going back to the chauffeur with my tail between my legs and saying to him ‘Well look, erm, John, the Queen Mother needs to be at this place at ten past nine. Could you possibly see your way to picking her up at, ooh, I don’t know, maybe ten to nine perhaps. How does that fit in with you? Would that be okay?’

To which he responded, ‘Of course I will, it’ll be a pleasure!’

I walked away thinking that the whole place was utterly mad.