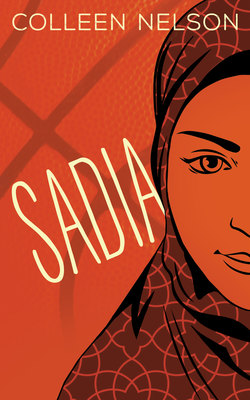

Читать книгу Sadia - Colleen Nelson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

Оглавление“Did you reply to Mr. Letner’s email about taking a camera home?” I asked my mom at dinner. She’d made one of Dad’s favourite meals, a spicy chicken dish, and our lips and fingers shone with grease.

“Yes,” she replied. “He’s an interesting teacher. Always with a new idea. You like his class?”

I nodded. “He wants us to take photos,” I explained to Dad. “About how we see the world.”

Aazim grinned at me. “The only thing you see is the basketball court.”

Since he’d started university, Aazim hadn’t been around as much as he used to be. He said he preferred to study at school, where it was quiet, as if the three of us were loud, rambunctious five-year -olds. “Not the only thing,” I said defensively.

He scoffed, wiping his fingers on a paper towel and leaving greasy smudges behind. “Your days of playing basketball are numbered, little sister.”

“No!”

“You’ll have to stop being a tomboy and become a dutiful Muslim woman, right?” He was teasing — we both knew our parents were fine with me playing sports. I kicked his shin under the table and he winced.

“Stop it, you two,” Dad said, raising an eyebrow and throwing Aazim and me a warning look that we knew better than to test. Dad’s skin was darker than mine or Mom’s, and when he did yardwork in the summer, it tanned a deep brown. His thick, curly black hair was unruly and always looked like it needed a cut.

“The email from Mr. Letner said you are supposed to take photos of things that matter to you. There’s more than just basketball. You should show your classmates what your life is like. It might be interesting for them.” I knew what Mom meant by life. She meant being Muslim. From the kitchen, I could see the small prayer mat in front of the window in the dining room. Mom used it five times a day for her prayers. Now that I was older, I’d started using it for my prayers, too. The mat had come with us from Syria and was soft from use. Dad had one in the bedroom, where he preferred to pray. He had one at his office, too.

I doubted kids at school would be interested in that, but instead of disagreeing with her, I gave a noncommittal shrug.

“Did you get your sociology exam back?” Dad asked Aazim.

Aazim shook his head. He attended the same university where Dad taught, but they rarely bumped into each other. Dad was an economics professor and spent his time in the Arts building, while Aazim was pre-med, according to my parents, or first year science, according to him. The one arts course Aazim had to take was Sociology, but he’d scheduled it to avoid bumping into Dad. “I saw you going into the Isbister Building today. I didn’t think you had any courses there.”

And that was the reason Aazim had carefully planned the location of his classes. Dad’s interest in his life was well meaning, but I knew it wore on Aazim.

“I don’t,” Aazim said with a frown. “Why were you there?” he added.

“I had a department meeting. We use the boardroom in that building.” I still wasn’t totally clear on what economics was. Dad said he sat around all day in his office, writing research papers. Sometimes, he’d teach a course if they let him. He was joking. I’d seen the letters and emails from students thanking him for being a great teacher. Dad loved to tell stories, and I had no doubt that he was able to entertain his students the same way he entertained Aazim and me. When we were kids, he didn’t read us bedtime stories, he told us tales that he’d been told by his father. A great actor, he had a different voice for each character and would play out the most exciting scenes, leaping from the bed to the floor until he had Aazim and me gripping the covers and barely breathing.

“I was just meeting some friends,” Aazim said, wiping his fingers again and leaving more greasy streaks behind. “Did you do anything today?” he asked Mom.

“Went to the grocery store, cooked, cleaned. The usual.” Mom sighed. “Although, I did see something interesting in the newspaper. The Millennium Library downtown is starting an Arabic section. There are a lot more Arabic speakers in the city now.”

“Maybe they’ll need a librarian?” I suggested.

“Maybe,” she said, although she sounded doubtful.

“Did you get any marks back?” Dad asked turning to me. Most of our dinner conversation centred around school: upcoming tests, studying for tests, and marks from tests. “No, but the tryouts for the tournament team started today.”

“Back to basketball,” Aazim mumbled.

“How did they go?” Mom asked. I saw tension flash on her face. Playing on a co-ed team was a bit of a tricky thing for us now that I was older. I knew they’d feel better once I was playing for an all-girls team, but making the tournament team was a big deal and I’d been excited when they’d agreed to let me try out.

“Fine, until I was hit in the face.” Everyone looked at me. I’d actually forgotten about it by the time I came home from school. The pain was gone, but my nose still felt swollen when I scrunched it up.

“What happened?” Mom peered at me. She wore wire-rimmed glasses that made her look even more like a librarian. Thin and tall, she had light brown eyes and wore a serious expression, like she was always thinking about something.

“A girl elbowed me in the nose. It was an accident. We were both going for the ball. It was bleeding, though, and I had to sit in the office for a while until it stopped.”

“Hmm. Maybe the game is too rough.”

I shook my head quickly. “It was my fault. I wasn’t paying attention. My scarf got in my face.”

My parents glanced at each other across the table. I held my breath. The last thing I needed was for them to decide basketball was too dangerous and tell me I couldn’t try out.

“Her nose wasn’t that great, anyway,” Aazim said. I gave him another kick to the shins as Mom and Dad laughed. Thanks to Aazim’s hilarious sense of humour, the matter of basketball being too dangerous was dropped.