Читать книгу The Enigma of Arthur Griffith - Colum Kenny - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Ballads, Songs and Snatches

Griffith had a musical ear, and it heard not only pleasant harmonies but also the voices of Irish people articulating in song their grief and scorn. He often crossed the Liffey to the Liberties, an old area of the city adjacent to Cook Street where his future wife lived until 1900. He met friends in the convivial surroundings of McCall’s ‘quaint old tavern’ at 25 Patrick Street. There, near St Patrick’s Cathedral, he would ‘listen to good talk about ballad poetry and old Dublin streets and people’. James Clarence Mangan had once frequented the pub, being a friend of an earlier McCall. At the time that Griffith used to go there ‘one could still be shown the actual place once favoured by Mangan, and even occupy his accustomed chair or bench’.1 Outside during the day, as an old photograph shows, a variety of street traders sold vegetables, shellfish and clothing among other items. Griffith also liked The Brazen Head pub nearby, with its table at which the patriot Robert Emmet was believed to have written. One of his earliest and strongest memories was said to have been of an ‘ancient’ female relative ‘who saw the dogs of Thomas St lap up a martyr’s blood [Emmet was executed there in 1803]’ singing defiantly ‘When Erin First Rose’.2

From an early age then Griffith was attuned to street ballads, which were a form of popular culture and a way to get a political message out. One of the first discussions of the Irish Transvaal Committee, when Griffith and Gonne decided to oppose Britain’s involvement in the Boer War, concerned ‘the practicability of utilising local ballad singers in singing appropriate songs against enlistment’.3 Griffith himself composed ballads for that purpose, with McCracken noting that, while ‘the Boer war did not throw up enduring works of literature, it did produce a rich literary legacy in the form of ephemeral doggerel. Much of this was written by Griffith’, some under his pen name Cuguan.4 He distinguished ballads from what he saw as the commercial vulgarity of music-hall singers with their English airs, complaining ‘They [our readers] have seen the old music forsaken for the jingles of Cockneydom, the songs that made men neglected for the things that reduce men to mere animals.’5

Patrick Street, Dublin, looking north, c.1895. McCall’s tavern is on the left (National Library of Ireland [L_ROY_05934]).

When he was fourteen, Griffith won copies of two books of Irish songs and ballads. They were awarded for his attendance and performance at Irish history classes of the Young Ireland Society, and were presented to him by the society’s president, veteran Fenian John O’Leary. According to a contemporary report, the books were Barry’s Songs of Ireland and a collection of ballads and poetry by ‘Duncathail’.6 On that day, O’Leary urged the rising generation to seek the ideal of Thomas Davis, whom Griffith was long to champion. It had been intended that Davis would, had he lived longer, edit the volume of ballads that Barry actually edited and that was first published in 1845. Barry, of whose collection Griffith now had a prize copy, informed readers that he ‘of course, rejected those songs which were un-Irish in their character or language, and those miserable slang productions, which, representing the Irishman only as a blunderer, a bully, a fortune-hunter, or a drunkard, have done more than anything else to degrade him in the eyes of others, and, far worse to debase him in his own’.7 Barry, like many other nationalists in the nineteenth century, contended with the stage-Irishman, with ‘humourous’ or other representations of his countrymen that were not merely a matter for literary critics to address. For, together with some cartoons in Punch magazine that represented Irish people as ape-like, such stereotypes served to pander to prejudice and imperialism.

Young Ireland had utilised ballads and song as a means of protesting and of galvanising support, and the Fenians of 1867 did likewise.8 In 1889 Griffith, aged eighteen, read to the Leinster Debating Club a short but entertaining paper on the topic.9 One striking feature of it was that the first and oldest ballad he cited was not nationalist in sentiment. He used this to make a point about street ballads generally:

Their influence at times has been remarkable. For instance, a ballad written by a noble lord in James II’s reign is said to have contributed not a little to his overthrow [by King William of Orange] – here is a verse:

There was an old prophecy found in a bog

Lillabulera Ballera la!

That Ireland would be ruled by an ass and a dog

Lillabulera Ballera la!

And now this old prophecy has come to pass

Lillabulera Ballera la!

For Talbot’s the dog and King James is the ass

Lillabulera Ballera la!

Griffith was quoting a song that became widely known before the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, and that his Ulster Protestant ancestors may well have sung. ‘Lillabulera’ (also ‘Lilliburlero’) is thought to have played a significant role in eroding public support for King James II. Its satirical, taunting lyrics were put to an old jig that Henry Purcell arranged and were sung by the supporters of ‘King Billy’. Its words were written in 1688 by Thomas Wharton, later a lord lieutenant of Ireland, and they satirised sentiments of the Catholic Irish that were then being voiced by royalist balladeers. Its opening line sets the tone: ‘Ho! Broder [brother] Teague, dost hear de decree?’ As seen above, the ballad has a sting in the tail for King James and his lord deputy Richard Talbot, earl of Tyrconnell (there was then a breed of dog used for tracking, especially on the battlefield, that was known as a Talbot). The refrain of the song may be an anglicised version of Irish words, perhaps ‘Lilly ba léir dó, ba linn an lá’ meaning ‘Lilly foretold it, this day would come.’ William Lilly (1602–81) was an immensely popular English astrologer.10 The air is played, to this day, by Orange bands, although with different lyrics and known as ‘The Protestant Boys’. A version of it also long served as the signature tune of the BBC World Service, despite the poet Robert Graves objecting to it.11 Such was its significance in Ireland under the Stuarts, that Bagwell equated its effect to that of The Marriage of Figaro in France before the French revolution and of John Brown’s March in the American civil war.12 It was said that forty thousand copies were circulated by the end of the 1680s and that the taking of Carrickfergus and the crossing of the Boyne were accompanied by the playing of it.13 It was not usually sung by nationalists.

As an editor, Griffith promoted the recovery and playing of Irish music and airs. His taste encompassed all sorts of ballads that he picked up on the streets. Any suggestion that Griffith was solely interested in the political content of his papers, while others took care of cultural or literary matters in them, is far too reductionist. Soon after Griffith’s death, George Lyons wrote ‘Among the most important and most beautiful achievements of Griffith was his “Ballad History of Ireland” which ran through the pages of The United Irishman from January 1904 till February 1905.’ Griffith’s brother Frank claimed that Brown’s Historical Ballad Poetry of Ireland was a ‘piece of piracy’ of Griffith’s work in the United Irishman.14 Griffith’s series was by no means all that he published on the topic of ballads, or on music more generally, and his body of work in that and other respects awaits further attention.15

Griffith’s friend William Rooney went to great lengths until his early death to find and have sung as many old Irish songs as he could discover, and Griffith kept up a campaign in support of Irish compositions and airs. As always, Griffith’s objective was to reinforce national self-esteem and to develop Irish economic and cultural activity. It is evident from reading his pieces in the United Irishman that he believed that some ostensibly highly cultured people patronised or scorned what was indigenous, and he would have none of it. On St John’s Eve 1910 young nationalist people gathered in Donnycarney near Dublin to celebrate midsummer, consciously adopting what they understood to be traditional customs of the old Irish on such special occasions. These included jumping over bonfires, which was perhaps once a fertility rite. They also sang popular nationalist songs, including ‘God Save Ireland’, ‘The Memory of the Dead’, ‘The Green Flag’ and ‘poor Fear na Muintear’s [the late William Rooney’s] “Men of the West”’. The United Irishman reported ‘we thought of the dark days of ten or twelve years ago, when William Rooney and his little band of comrades were sneered and jibed at as foolish dreamers and mad enthusiasts by the “practical men”’.16 James Joyce remembered a quieter visit to the same district:

O, it was out by Donnycarney

When the bat flew from tree to tree

My love and I did walk together;

And sweet were the words she said to me.17

Griffith’s private secretary during the treaty negotiations in London wrote that ‘Griffith liked good music, and had a sweet, weak singing voice … He liked patriotic love songs such as The Foggy Dew or Maire my Girl’.18 Interned with him in England, a future minister for finance, Ernest Blythe, discovered that ‘Griffith had an extraordinary knowledge of Irish music. No matter what tune was mentioned in any discussion he was able to whistle it. He must have had at least hundreds of tunes in his mind.’19 Griffith also liked arias from some of the well-known operas that were performed regularly in Dublin, with patrons of different social classes mingling at performances. He could be heard singing them aloud. James Joyce had a better singing voice than Griffith and even came close to winning the tenor competition of the annual Feis Ceoil. He shared with Griffith a taste for the everyday and is said to have known hundreds of songs ‘composed by Irish men and women … about wars, battles, patriotism, nature, love, drinking, all in an Irish context … known and sung by the Irish’. They included ‘The Memory of the Dead’ and some other pieces that featured in the talk about the ‘songs of our fathers’ that Griffith gave publicly in 1899.20 Joyce’s short, well-known story ‘The Dead’ poignantly evokes the kind of recreational evening of mixed song, piano accompaniment and recitation that was long a feature of Dublin life, especially at Christmas even into the present author’s youth, and that Griffith and his friends enjoyed in their societies.

Imprisoned with Griffith in Gloucester during the Irish War of Independence, Robert Brennan was fascinated by his knowledge of song:

There was no opera which I had seen, up to that time, which was strange to A.G. Now and again he used to sing snatches from The Barber of Seville or Faust, but never for an audience. He had rather a poor baritone voice, but he whistled very well. He was a typical Dubliner in his fondness for Wallace and Balfe, and as for drama, he knew his Congreve, Sheridan, and Goldsmith very well. He had a keen appreciation of Shakespeare and Beaumont and Fletcher. He knew and loved every melodrama that had been produced in the Queen’s Theatre for a generation.21

Later, during the strained weeks in London embroiled in negotiations for an Anglo-Irish Treaty, Griffith took himself off as a respite to the Hammersmith Theatre to enjoy its new production of The Beggar’s Opera. On 27 October 1921, he did so with Michael Collins and Kitty Kiernan.22

Across the table from Griffith at the negotiations in Downing Street sat Winston Churchill, whose father and Arthur Balfour had both featured in a satirical ballad which, in 1889, Griffith had quoted in his paper for the Leinster Debating Club – but he presumably did not sing this to his select audience in Whitehall.23

After Griffith died, Piaras Béaslaí edited a pamphlet containing two dozen ballads that Griffith himself had composed. These ranged from the fiercely political ‘Twenty Men from Dublin Town’, which sings of United Irishmen who left Dublin after the 1798 insurrection and joined the rebellious Michael Dwyer in the mountains, to his humourous ‘Thirteenth Lock’. This features the drunken skipper of a canal barge negotiating Dublin’s Grand Canal by Dolphin’s Barn and Inchicore. It takes sideswipes along the way at certain Trinity College professors who were hostile to the Irish language.

Visiting Paris, Griffith was impressed by J.B. Duffaud’s painting ‘Les Anglais en Irlande 1798’, referencing the French-backed rebellion in Ireland that year,24 and a number of times called for Irish artists to paint significant historical scenes. He thought that the Irish also deserved new theatrical works of art that that would be accessible. Referring to those ‘known in England as the lower-middle-class and bred on Poe, Cowper and Macaulay’, he wanted for their Irish counterparts ‘[a] few simple farces and ordinary plays on conventional lines, with an Irish flavour … Shapespeare wrote Julius Caesar and his Lucretia for this class, and his Hamlet and his Sonnets for the other’. Griffith warned in fatherly fashion that as regards such Irish people, ‘symbolism affrights them as darkness does a child’.25

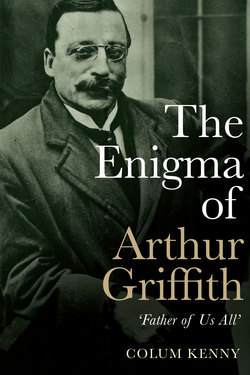

Some of Griffith’s verses, published after he died. On the cover is the portrait of Griffith by Lily Williams now in Dublin City Gallery/The Hugh Lane.