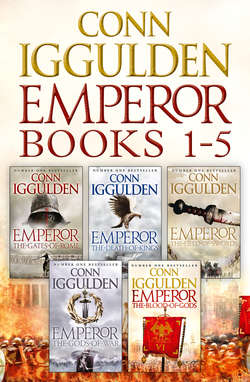

Читать книгу The Emperor Series Books 1-5 - Conn Iggulden - Страница 61

CHAPTER NINE

Оглавление‘I have no idea what you are talking about,’ Fercus said. He strained against the ropes that held him to the chair, but there was no give in them.

‘I think you know exactly what I mean,’ Antonidus said, leaning in very close so that their faces almost touched. ‘I have a gift for knowing a lie when I am told one.’ He sniffed twice suddenly and Fercus remembered how they called him Sulla’s dog.

‘You reek of lies,’ Antonidus said, sneering. ‘I know you were involved, so simply tell me and I will not have to bring in the torturers. There is no escape from here, broker. No one saw you arrested and no one will know we have spoken. Just tell me who ordered the assassination and where the killer is and you will walk out unharmed.’

‘Take me to a court of law. I will find representation to prove my innocence!’ Fercus said, his voice shaking.

‘Oh, you would like that, wouldn’t you? Days wasted in idle talk while the Senate tries to prove it has one law for all. There is no law down here, in this room. Down here, we still remember Sulla.’

‘I know nothing!’ Fercus shouted, making Antonidus move back a few inches, to his relief.

The general shook his head in regret.

‘We know the killer went by the name of Dalcius. We know he had been bought for kitchen work three weeks before. The record of the sale has vanished, of course, but there were witnesses. Did you think no one would notice Sulla’s own agent at the market? Your name, Fercus, came up over and over again.’

Fercus paled. He knew he would not be allowed to live. He would not see his daughters again. At least they were not in the city. He had sent his wife away when the soldiers came for the slave market records, understanding then what would happen and knowing he could not run with them if he wanted them to escape the wolves Sulla’s friends would put on his trail.

He had accepted that there was a small risk, but after burning the sale papers, he had thought they would never make the link among so many thousands of others. His eyes filled with tears.

‘Guilt overwhelms you? Or is it just that you have been found out?’ Antonidus asked sharply. Fercus said nothing and looked at the floor. He did not think he could stand torture.

The men who entered at Antonidus’ order were old soldiers, calm and untroubled at what they were asked to do.

‘I want names from him,’ Antonidus said to them. He turned back to Fercus and raised his head until their eyes met once more. ‘Once these men have started, it will take a tremendous effort to make them stop. They enjoy this sort of thing. Is there anything you want to say before it begins?’

‘The Republic is worth a life,’ Fercus said, his eyes bright.

Antonidus smiled. ‘The Republic is dead, but I do love to meet a man of principle. Let’s see how long it lasts.’

Fercus tried to pull away as the first slivers of metal were pressed against his skin. Antonidus watched in fascination for a while, then slowly grew pale, wincing at the muffled, heaving sounds Fercus made as the two men bent over him. Nodding to them to continue, the general left, hurrying to be out in the cool night air.

It was worse than anything Fercus had ever known, an agony of humiliation and terror. He turned his head to one of the men and his lips twisted open to speak, though his blurring eyes could not see more than vague shapes of pain and light.

‘If you love Rome, let me die. Let me die quickly.’

The two men paused to exchange a glance, then resumed their work.

Julius sat in the sand with the others, shivering as dawn finally came to warm them. They had soaked the clothes in the sea, removing the worst of months of fetid darkness, but they had to let them dry on their bodies.

The sun rose swiftly and they were silent witnesses to the first glorious dawn they had seen since standing on the decks of Accipiter. With the light, they saw the beach was a thin strip of sand that ran along the alien coast. Thick foliage clustered right up to the edge of it as far as the eye could see, except for one wide path only half a mile away, found by Prax as they scouted the area. They had no idea where the captain had put them down, except that it was likely to be near a village. For the ransoms to be a regular source of funds, it was important that prisoners made it back to civilisation and they knew the coast would not be uninhabited. Prax was sure it was the north coast of Africa. He said he recognised some of the trees and it was true that the birds that flew overhead were not those of home.

‘We could be close to a Roman settlement,’ Gaditicus had said to them. ‘There are hundreds of them along the coast and we can’t be the first prisoners to be left here. We should be able to get on one of the merchant ships and be back in Rome before the end of summer.’

‘I’m not going back,’ Julius had said quietly. ‘Not like this, without money and in rags. I meant what I said to the captain.’

‘What choice do you have?’ Gaditicus replied. ‘If you had a ship and a crew you could still spend months searching for that one pirate out of many.’

‘I heard one of the guards call him Celsus. Even if it’s not his real name, it’s a start. We know his ship and someone will know him.’

Gaditicus raised his eyebrows. ‘Look, Julius. I would like to see the bastard again as much as you, but it just isn’t possible. I didn’t mind you baiting the idiot on board, but the reality is we don’t have a sword between us, nor coins to rub together.’

Julius stood and looked steadily at the centurion. ‘Then we will start by getting those, then men to make a crew, then a ship to hunt in. One thing at a time.’

Gaditicus returned the gaze, feeling the intensity behind it. ‘We?’ he said quietly.

‘I’d do it alone if I had to, though it would take longer. If we stay together, I have a few ideas for getting our money back so we can return to Rome with pride. I won’t creep back home beaten.’

‘It’s not a thought I enjoy,’ Gaditicus replied. ‘The gold my family sent will have pushed them all into poverty. They will be happy to see me safe, but I will have to see how their lives have changed every day. If you aren’t just dreaming, I will listen to those ideas of yours. It can’t hurt to talk it through.’

Julius put out his hand and gripped the older man’s shoulder, before turning to the others.

‘What about the rest of you? Do you want to go back like whipped dogs or take a few months more to try and win back what we have lost?’

‘They will have more than just our gold on board,’ Pelitas said slowly. ‘They wouldn’t be able to leave it anywhere and be safe, so there’s a good chance the legion silver will be in the hold as well.’

‘Which belongs to the legion!’ Gaditicus snapped with a trace of his old authority. ‘No, lads. I’ll not be a thief. Legion silver is marked with the stamp of Rome. Any of that goes back to the men who earned their pay.’

The others nodded at this, knowing it was fair.

Suetonius spoke suddenly in disbelief.

‘You are talking as if the gold is here, not on a distant ship we will never see again while we are lost and hungry!’

‘You are right,’ Julius said. ‘We had better get started along that path. It’s too wide to be just for animals, so there should be a village hereabouts. We’ll talk it out when we have a chance to feel like Romans again, with good food in our bellies and these stinking beards cut off.’

The group rose and walked towards the break in the foliage with him, leaving Suetonius alone, his mouth hanging open. After a few moments, he closed it and trotted after them.

The two torturers stood silently as Antonidus viewed the wreck that had been Fercus. The general winced in sympathy at the mangled carcass, glad that he had been able to enjoy a light sleep while it was going on.

‘He said nothing?’ Antonidus asked, shaking his head in amazement. ‘Jupiter’s head – look what you’ve done to him. How could a man stand that?’

‘Perhaps he knew nothing,’ one of the grim men replied.

Antonidus considered it for a moment.

‘Perhaps. I wish we could have brought his daughters to him so I could be sure.’

He seemed fascinated by the injuries and inspected the body closely, noting each cut and burn. He whistled softly through his teeth.

‘Astonishing. I would not have believed he had such courage in him. He didn’t even try to give false names?’

‘Nothing, General. He didn’t say a word to us.’

The two men exchanged a glance again, hidden behind the general’s back as he bent close to the bound corpse. It was a tiny moment of communication before they resumed their blank expressions.

Varro Aemilanus welcomed the ragged officers into his house with a beaming smile. Although he had been retired from legion life for fifteen years, it was always a pleasure to see the young men the pirates left on his small stretch of coast. It reminded him of the world outside his village, distant enough not to trouble his peaceful life.

‘Sit down, gentlemen,’ he said, indicating couches that were thinly padded. They had been fine once, but time had taken the shine from the cloth, he noted with regret. Not that these soldiers would care, he thought as they took the places he indicated. Only two of them remained standing and he knew they would be the leaders. Such little tricks gave him pleasure.

‘Judging by the look of you, I’d say you have been ransomed by the pirates that infest this coastline,’ he said, his voice drenched in sympathy. He wondered what they would say if they knew that the pirate Celsus often came to the village to talk to his old friend and give him the news and gossip of the cities.

‘Yet this settlement is untouched,’ said the younger of the two.

Varro glanced sharply at him, noting the intense blue stare. One of the eyes had a wide, dark centre that seemed to look through his cheerful manner to the real man. Despite the beards, they all stood straighter and stronger than the miserable groups Celsus would leave nearby every couple of years. He cautioned himself to be careful, not yet sure of the situation. At least he had his sons outside, well armed and ready for his call. It paid to be careful.

‘Those they have ransomed are left along this coast. I’m sure they find it useful to have the men returned to civilisation to keep the ransoms coming in. What would you have us do? We are farmers here. Rome gave us the land for a quiet retirement, not to fight the pirates. That is the job of our galleys, I believe.’ He said the last with a twinkle in his eye, expecting the young man to smile or look embarrassed at failing in that task. The steady gaze never faltered and Varro found his good humour evaporating.

‘The settlement is too small for a bath-house, but there are a few private homes that will take you in and lend you razors.’

‘What about clothes?’ said the older of the two.

Varro realised he didn’t know their names and blinked. This was not the usual way of such conversations. The last group had practically wept to find a Roman in such a strange land, sitting on couches in a well-built stone house.

‘Are you the officer here?’ Varro asked, glancing at the younger man as he spoke.

‘I was the captain of Accipiter, but you have not answered my question,’ Gaditicus replied.

‘We do not have garments for you, I am afraid …’ Varro began.

The young man sprang at him, gripping his throat and pulling him out of his seat. He choked in horror and sudden fear as he was dragged over the table and pressed down onto it, looking up into those blue eyes that seemed to know all his secrets.

‘You are living in a fine house for a farmer,’ the voice hissed at him. ‘Did you think we wouldn’t notice? What rank were you? Who did you serve with?’

The grip lessened to let him speak and Varro thought of calling to his sons, but knew he didn’t dare with the man’s hand still on his throat.

‘I was a centurion, with Marius,’ he said hoarsely. ‘How dare you …’ The fingers tightened again and his voice was cut off. He could barely breathe.

‘Rich family, was it? There are two men outside, hiding. Who are they?’

‘My sons …’

‘Call them in here. They will live, but I’ll not be ambushed as we leave. You will die before they reach you if you warn them. My word on it.’

Varro believed him and called to his sons as soon as he had the breath. He watched in horror as the strangers moved quickly to the door, grabbing the men as they entered and stripping their weapons from them. They tried to shout, but a flurry of blows knocked them down.

‘You are wrong about us. We live a peaceful life here,’ Varro said, his voice almost crushed from him.

‘You have sons. Why haven’t they returned to Rome to join the armies like their fathers? What could hold them here but an alliance with Celsus and men like him?’

The young officer turned to the soldiers who held Varro’s sons.

‘Take them outside and cut their throats,’ he said.

‘No! What do you want from me?’ Varro said quickly.

The blue eyes fastened on his again.

‘I want swords and whatever gold the pirates pay you to be a safe place for them. I want clothes for the men and armour if you have it.’

Varro tried to nod, with the hand still on his neck.

‘You will have it all, though there’s not much coin,’ he said, miserably.

The grip tightened for a second.

‘Don’t play false with me,’ the young man said.

‘Who are you?’ Varro wheezed at him.

‘I am the nephew of the man you swore to serve until death. My name is Julius Caesar,’ he said quietly.

Julius let the man rise, keeping his face stern and forbidding while his spirits leapt in him. How long ago had Marius told him a soldier had to follow his instincts at times? From the first instant of walking into the peaceful village, noting the well-kept main street and the neat houses, he had known that Celsus would not have left it untouched without some arrangement. He wondered if all the villages along the coast would be the same and felt a touch of guilt for a moment. The city retired their legionaries to these distant coasts, giving them land and expecting them to fend for themselves, keeping peace with their presence alone. How else could they survive without bargaining with the pirates? Some of them might have fought at first, but they would have been killed and those that followed had no choice.

He looked over to Varro’s sons and sighed. Those same retired legionaries had children who had never seen Rome, providing new men for the pirate ships when they came. He noted the dark skin of the pair, their features a mingling of Africa and Rome. How many of these would there be, knowing nothing of their fathers’ loyalties? They could never be farmers any more than he could, with a world to see.

Varro rubbed his neck as he watched Julius and tried to guess at his thoughts, his spirits sinking as he saw the strange eyes come to rest on his beloved sons. He feared for them. He could feel the anger in the young officer even now.

‘We never had a choice,’ he said. ‘Celsus would have killed us all.’

‘You should have sent messages to Rome, telling them about the pirates,’ Julius replied distantly, his thoughts elsewhere.

Varro almost laughed. ‘Do you think the Republic cares what happens to us? They make us believe in their dreams while we are young and strong enough to fight for them, but when that is all gone, they forget who we are and go back to convincing another generation of fools, while the Senate grow richer and fatter off the back of lands we have won for them. We were on our own and I did what I had to.’

There was truth in his anger and Julius looked at him, taking in the straighter bearing.

‘Corruption can be cut out,’ he said. ‘With Sulla in control, the Senate is dying.’

Varro shook his head slowly.

‘Son, the Republic was dying long before Sulla came along, but you’re too young to see it.’

Varro collapsed back into his seat, still rubbing his throat. When Julius looked away from him, he found all the officers of Accipiter watching him, waiting patiently.

‘Well, Julius?’ Pelitas said quietly. ‘What do we do now?’

‘We gather what we need and move on to the next village, then the next. These people owe us for letting the pirates thrive in their midst. I do not doubt there are many more like this one,’ he replied, indicating Varro.

‘You think you can keep doing this?’ Suetonius said, horrified at what was happening.

‘Of course. Next time, we will have swords and good clothes. It will not be so hard.’