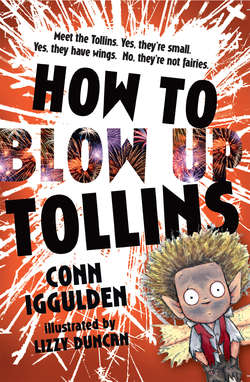

Читать книгу HOW TO BLOW UP TOLLINS - Conn Iggulden - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

THE YEAR 1922, DURING THE REIGN OF KING GEORGE V

Tollins are not fairies. Though they both have wings, fairies are delicate creatures and much smaller. When he was young, Sparkler accidentally broke one and had to shove it behind a bush before its friends noticed.

In addition, fairies cannot sing B-sharp. They can manage a very nice B-flat, in quite a sweet voice, but B-sharp comes out like a frog being run over by a bicycle. Tollins regard fairies as fluttery show-offs and occasionally use them to wipe out the insides of cups. Tollins are also a lot less fragile than fairies. In fact, the word ‘fragile’ can’t really be used about them at all. They are about as fragile as a housebrick.

Before that summer when the world changed, Sparkler had looked forward to a full life containing nothing more dangerous than wrestling angry bees off flowers, or occasionally dancing with other Tollins at the full moon. He loved to dance, even when he trod on the toes of the others, or tripped over a fairy ring. Fairies never tripped, or fell over, so when they tried to take part, Tollins always began a singing competition instead. In the key of B. If the fairies stamped their little feet and rose to the challenge, they sounded like silver bells being dunked in soup before they gave up. Tollins enjoyed that.

When Sparkler was born, his parents enjoyed a simple life of fluttering around at the bottom of people’s gardens. The most exciting thing that had ever happened to them was being chased by two little girls, until they were fortunately distracted by a pony. Adults were no danger. They just couldn’t see Tollins, even if they were really close.

At first, the Tollins had thought nothing of the serious men with large beards and even larger boots who suddenly seemed to be everywhere, measuring things with bits of string and nodding to each other. Yet in just a short time, they had transformed the little village of Chorleywood. First they had run rails for clanking trains, then they built their firework factory. It had very thick walls and an extremely thin roof, just in case.

The Tollins hadn’t minded the fireworks being tested. Some nights, Sparkler had gathered with his parents and grandparents to watch the serious, bearded men light them, one after the other. None of the fireworks went whee or had colours back then*. They just went bang and made the men jump and clap their hands together, almost like the children they had once been.

The ‘Great Firework Discovery’ had been an accident, really. One of the youngest Tollins had crept too close to a firework on the bench of the factory. While no one was around, the little one climbed into the tube of something called a ‘Roman Candle’. Just as he was tasting a pinch of the black powder inside, it all went dark and he was trapped.

The other Tollins searched for him, of course, but there was no sign. That night, the first fireworks were the usual sort, jumping and spluttering, but then the Roman Candle was lit, and the world changed forever.

Sparkler had been there, sitting on a wall with his family. He still remembered the way the Roman Candle leapt into the air, trailing a shower of blue sparks before exploding with a bang that knocked one of the men down. The man’s beard was on fire when he stood up, but that didn’t stop him cheering as he patted the flames out.

In the silence, in the night air, the Tollins heard the voice of the little one they had lost.

“Heeeeelp!” he yelled. The older Tollins looked at each other and their wings vibrated so fast you could hardly see them. They leapt up into the darkness and one of them caught the little Tollin as he fell.

He was bruised but alive, though his wings were in tatters. Those would grow back in time, but he also seemed to have gone deaf and couldn’t understand the questions they were all asking.

“What?” he kept saying. “I was in the firework! No, in it! Didn’t you see? What?”

Deep under Chorleywood station, the High Tollin had called a council of seniors together to discuss the problem. While his parents spoke at the meeting, Sparkler had tended to the burned one who kept shouting ‘What?’ The little one’s name had been Cherry, but he insisted they call him ‘Roman’ after that.

Tollins had come into contact with humans before. They were too curious for their own good and humans always seemed to be doing something interesting. Small Tillets were still told the tale of the Tollin who wrestled an apple off a tree and dropped it on the head of a young man sleeping below. The young man’s name was Isaac Newton and, as a result, he discovered gravity.

As a young Tillet, Sparkler had even spent time at a school, when he overslept in a satchel. He still cherished the memories of the little book he had brought home, full of big letters and pictures of apples and bees. The bees smiled from the page, which was surprising. In Sparkler’s experience, bees had no sense of humour.

Just taking that book had been an enormous risk. After all, the first Tollin law was that no one spoke to humans. It always led to trouble, or sometimes gravity. It was better for Tollins if humans didn’t know they existed. After all, Tollins weren’t fast, or even particularly nimble. Over the years, they had been caught by propellers, run over by lawn mowers and one had become tangled in a kite string until he bit through it. They might not have been fast, but they were tough. One of them had even been swallowed by a cat and she survived too, but the less said about that the better.

In the end, the High Tollin decided no lasting harm had been done. He couldn’t have known then that the men with beards were more excited about the new kind of firework than they were about big ships, good boots and proper penknives put together. Seeing young Roman whoosh above their heads had been the most interesting moment of their lives and they would not rest until they had managed to do it again. If the Tollins had known then about Catherine wheels, perhaps they might have flown to a different part of the country, joining the Dark Tollins of Dorset, or the Mountain Tollins of Wales. They could even have stowed away on a ferry to another country, where Tollins spoke in a strange accent and wore berets. If they had, it would have saved them from headaches, exhaustion, fallen arches and worst of all, slavery.

* Some people have suggested that Chinese Tollins were used in fireworks more than a thousand years ago. This is NOT that story.