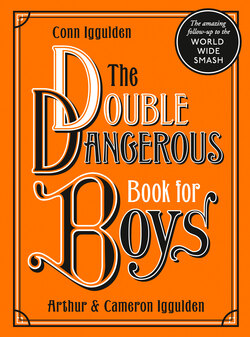

Читать книгу The Double Dangerous Book for Boys - Conn Iggulden - Страница 11

ОглавлениеOLD BRITISH COINS

Left. Ivan Vdovin/Alamy Stock Photo; Right. Simon Evans/Alamy Stock Photo

Each generation loses some old knowledge – and learns something new. Along with death and taxes, this is one of life’s certainties. Over passing centuries or millennia it can lead to great shifts in ‘general knowledge’. What was once known to all can become the knowledge only of specialists – or lost for ever.

Our task is not to preserve the past for its own sake. There are many thousands of books and plays that refer to the pre-decimal coinage of Britain. We include a brief sampler here of those coins. It would not feel quite right if no child today knew that there were once twelve pennies in a shilling, or two hundred and forty pennies in a pound.

The first coins to circulate in Britain were gold staters from ancient Gaul, imported around 150 BC. The designs suggest they were influenced by Macedonian coins of King Philip II, father to Alexander the Great. Coin production in Britain began some fifty years later, around 100 BC. These ancient coins, like those of Rome, were made of gold, silver or bronze. The three metals seem to form the basis of all ancient coin systems. Gold is eternal – it does not rust – so has always been a symbol of perfection and high value in almost every human society. Silver is attractive, but goes black very easily. Like bronze, however, silver has a relatively low melting point and is easy to mine and work. That probably explains its popularity, along with tin and copper. Those metals are all soft enough to be hand-stamped with a hammer. In the early British coins, the images stamped on them were very varied. They included horses, helmets, faces, stags, wreaths and a host of other pictures without words. Most people could not read, after all.

From the first Roman invasion in 55 and 54 BC, Britain came into the orbit of the Roman world. After AD 45, Roman coins circulated as well as native ones. The metal itself had value, so could be exchanged for others with a different design or origin. The Cantii tribe in Kent produced their own coins, as did the Trinovantes, the Catuvellauni and the Iceni in Norfolk under Boadicea, who led an uprising against the Romans in the 1st century AD.

The Roman empire produced many coins – not only for all its emperors, but also to mark military successes and key festivals. As well as gold aureus coins, they issued silver denarius coins (denarii in the plural: den-ar-i-eye) and sestertius coins (sestertii: sest-ur-tee-eye) in silver or brass. There was also a bronze coin called an as.

After the Roman legions left Britain and their last officials were expelled in AD 410, coins were still minted north and south – the silver penny became virtually the sole coin in common use for at least five centuries. It was still referred to as a ‘denarius’, or ‘d’ for short. Though it became a copper coin in later centuries, the habit of labelling a penny as ‘1d’ continued right up to decimalisation in 1971.

Rulers of small kingdoms such as Mercia or East Anglia would issue their own silver coins, as did established Viking invaders around York. By the 10th century, King Æthelstan, the first king of England and Scotland, organised the mints and closed down a lot of fake coin shops.

After 1066, King William of Normandy maintained the Anglo-Saxon regional mint system, but over time it became more centralised. Coins that could be cut into halves and quarters were a brief experiment, but not popular. In 1180, Henry II put his name ‘Henricus’ and ‘Rex’ (king) on his coins, though it did not become standard practice for his sons Richard and John.

Short-cross coin of Henry II, issued 1180–1189

AMR Coins

By the 13th century, under King Edward I, the minting of coins had become a royal activity and was restricted to London, Canterbury, Durham and Bury. In 1279, new coins were produced: the first halfpenny, a ‘farthing’ quarter-penny and a groat, worth fourpence. The name of ‘Edward’ appeared on them all.

A fourpenny piece – the ‘groat’

Courtesy of the author

In the 14th century, during the long reign of Edward III, gold coins made a return, with the introduction of the gold florin and the gold noble and half-noble. Intricate designs could be stamped on gold and they were still the symbol of great wealth. Silver pennies, halfpennies and farthings also continued to be issued. Those were the main denominations up to King Henry VI, Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses, when the wonderfully named gold angel and half-angels were also issued – a reference to the design of the Archangel Michael killing a dragon stamped on the coin.

The gold ‘angel’

Left. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, UK/Bridgeman Images; Right. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2019/Bridgeman Images

As the first Tudor, King Henry VII made changes in 1489. A pound by weight of sterling silver had been a unit of measurement for centuries, but no pound coin had ever been issued. Henry Tudor issued the first – and as the design included the king on a throne, called it a sovereign. Double- and even triple-weight sovereigns were also issued. Sovereigns have been issued by every monarch since then, a practice that continues today. They are still made of gold and are very valuable.

The first pound coin – the ‘sovereign’

Universal History Archive/UIG/Bridgeman Images

The first shillings, coins worth twelve pennies, were produced by Henry VII and known then as ‘testoons’ or ‘head-pieces’ – as they had his head printed on them. He and his son Henry VIII debased the level of silver in the coins, a practice that was just too tempting. Mixing silver with cheaper metals meant two coins could be produced for the same amount of silver – or four, or twelve … The history of coins is also the history of forgery and cheating. Queen Elizabeth I recalled many of these cheap coins and reissued higher-quality ones.

The explosion of commerce in the Elizabethan age required sixpence and threepence coins marked with a rose, as well as the shilling, groat, penny, halfpenny and farthing. She also issued crowns, worth five shillings, and half-crowns, worth two shillings and sixpence. They were issued from the brief reign of her older brother Edward to 1967.

Elizabethan shilling – a very modern coin

Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

In 1660, King Charles II was restored to the throne after the years under Cromwell. In 1663, the first machine-produced coins were made, consigning hand-stamping to history. Coins could then be milled with great precision. Some even had the words ‘Decus and Tutamen’ cut into the edge – ‘an ornament and a shield’ – to protect them from being clipped. The gold used in these coins came from Guinea in Africa, so they became known as the first guineas. Originally, they were worth twenty silver shillings. Later, they became worth twenty-one shillings, or a pound and a shilling. Guineas are still used in some racehorse auctions, where it is possible to bid a thousand pounds and have the bid raised with the word ‘guineas’ – one thousand and fifty pounds. Charles II also issued copper coinage for the first time and tin/copper coins to help the Cornish tin industry.

In 1797, the government issued copper pennies, though when copper became scarce, they changed to bronze around 1860. Still called ‘coppers’, bronze halfpennies, farthings and even third-farthings were issued as the 19th century went on.

At the start of the 20th century, the currency was stable and produced by a royal mint. King Edward VII and then King George V had their image on coins ranging from a third of a farthing up to a five-pound gold coin. Over time, smaller coins began to be less useful. The ‘inflation’ of currency meant that prices went up and money was not worth as much. Farthings were dropped around 1960.

Queen Elizabeth II began her reign in 1952 with a currency based around the number twelve, with a history stretching back to ancient Rome. When the symbols for pounds, shillings and pence were written, it was always ‘£, s and d’ – the last, as we’ve seen, for denarius. In 1970, Britain still used the halfpenny, the penny, the threepenny bit, the silver sixpence, the shilling, the florin (two-shilling piece), the half-crown (two shillings and sixpence), the crown (five shillings), the half-sovereign (ten shillings), the sovereign (twenty shillings or £1) – and the guinea of twenty-one shillings. My mother told a story of when she was a young girl and found her father asleep in an armchair. Kneeling beside him, she whispered, ‘Can I have a half-crown?’ into his ear. When there was no response, she crept around to the other side and whispered, ‘Can I have a crown?’ into that ear. There was silence for a time, then without opening his eyes, he murmured, ‘Go back to the half-crown ear.’

In 1971, the government of Prime Minister Edward Heath formally abolished the old coin values and went to a decimal system (based on the number ten). He hoped to modernise Britain, breaking those ties to the ancient past. New coins were issued, with the five-pence piece referred to as a shilling to help with the transition. A pound was redesignated as 100 pennies, so that the 5p piece was still one-twentieth. New green one-pound notes were issued, replaced in 1983 by the first pound coins. Later, two-pound coins were issued for normal use. Some special-edition five-pound coins are produced each year and gold sovereigns are still minted. The bank notes at the time of writing are for five, ten, twenty and fifty pounds.

It is worth noting that these are artificial systems. Whether a pound (or a dollar) has a hundred pennies or 60, 240 or even 360 is a matter of choice. We chose to keep 60 minutes in an hour, 360 degrees in a circle and 24 hours in a day. Yet some numbers are just more useful than others. 240 has 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 20, 24, 30, 40, 48, 60, 80, 120 and 240 itself as factors – 20 in all. In comparison, 100 has 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50 and 100 itself – just nine factors. In that way, 240 is more useful than 100, both in trade and in teaching maths.

The history and stability of a country can be read in its currency – and knowing the road behind can be useful in judging the road ahead. Of course, it is possible that before the 21st century comes to an end, all transactions will have become digital and coins will have gone the way of the dinosaurs. That would be a shame – there is something comforting about a handful of change clinking in a pocket – along with two thousand years of history.