Читать книгу Irish Days, Indian Memories - Conor Mulvagh - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

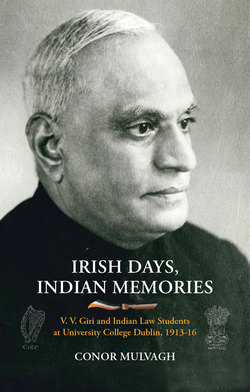

In writing a history of the intersections between Irish and Indian nationality, this book is intended to appeal to two different audiences. To Irish readers, this short book offers an insight into a virtually unknown section of Dublin’s political and student life between 1913 and 1916. Among them was V. V. Giri, fourth President of India (1969–74) who would later say of himself ‘when I am not an Indian, I am an Irishman’.1 The diversity of Dublin in this era is something which still warrants analysis and it is hoped that this study will incorporate the story of Indian students into Ireland’s wartime and insurrectionary experiences. In charting the social history of Dublin as lived by Indian students in this era, I have endeavoured to present the positive and negative aspects of these interactions without dilution and, I hope, with a balance that reflects accurately the realities of the time. I am conscious that the negative aspects of encounter have a propensity to be over-represented in the archive. It is thus important to state that the best overall evidence of how well Indian students integrated into Irish life can be found in the fact that so many of their contemporaries and classmates treated them as equals and that they progressed through their studies in Dublin as peers, finding acceptance and friendship not only in the lecture theatre but in student societies, at the dinner table and in the social outlets of the city.

To Indian readers, it is hoped that what is offered here is a detailed insight into the Irish experiences of V. V. Giri, whose three-year stay in Dublin to study law between 1913 and 1916 left a lifetime legacy. Giri was one of UCD’s first identifiable groups of international students. He arrived in Dublin in the late summer of 1913 along with twelve other Indian students. While the fact that Giri studied in Dublin is well known in India, the details of his time here remain impressionistic in the historiography. Furthermore, the retrospective prominence of Giri among Dublin’s Indian students has served to eclipse his compatriots who joined him here to live and study. I hope that this book goes some way to uncovering some of those occluded stories and, by so doing, adds depth and context to the story of V. V. Giri’s Dublin days.

Writing the history of Indian students in pre-independence Ireland has been a challenging but highly rewarding exercise. For one accustomed to standing on firmer historical ground, this study has forced me to venture further away from archival terra firma than usual. On the face of it, the persons at the centre of this study are almost ghosts. They have left their names in the records of the institutions in which they studied, their lodging houses have been found, and other valuable snippets of functional contemporary detail about their lives have been uncovered. However, as to their lived experiences in Dublin of a century ago, the author has been forced to rely on very scant material indeed. Thankfully this has been enhanced by the existence of a variety of memoirs and oral testimony written and recorded decades after the fact.

It is important to emphasise that this is by no means a definitive study of Indian law students in Dublin. Really, it only represents a starting point which I hope will be of benefit to scholars working on the diversity of Dublin life in this period and also to those interested in the history of international education in Ireland. Only those students who attended UCD are included in this study. By definition, these students also studied at the King’s Inns but, as will be shown, a number of Indian students combined their studies at the King’s Inns with periods of study at Trinity College Dublin and, it seems, British universities as well. This study finds a logical end-point in 1916. However, Indian law students built lasting associations with Dublin. It stands to future scholars to write a fuller history of these connections and to write the history of international legal education in Dublin more generally.

V. V. Giri, the figure at the centre of this study, left a vivid and lively account of his Dublin days in his autobiography, written in the 1970s. It was difficult to substantiate much of what Giri recounted in this memoir. On first reading, much of what he claimed seemed too fantastic to be true. The fact that Giri’s presidential staff had written to the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs in 1972 and 1973 requesting books on Irish history to assist Giri in the composition of his memoirs raises a question mark over the originality of Giri’s recollections. However, time and again, the claims made by Giri have been substantiated, often in unlikely places. A catalogue of Indian proscribed tracts proved the existence of a pamphlet of which Giri claimed to have been one of the leading organisers; the claim that Thomas MacDonagh lectured Giri has been supported by minutes in the records of UCD’s Academic Council; furthermore, links between Indian students and the Irish Volunteers have also been verified. In this light, those elements which remain unsubstantiated by archival sources such as police raids and the facts around Giri’s deportation become less far-fetched. Despite the amount of time which has elapsed since Ireland’s revolutionary decade, new material continues to surface or be released which will perhaps shed further light on aspects of Giri’s story in years to come. In uncovering links between Irish and Indian nationalists, the release of the Bureau of Military History witness statements by Ireland’s Military Archives in recent years has provided essential substantiating evidence. This army-led oral history project about Ireland’s revolutionary period was conducted in the late 1940s and early 1950s but only made public in 2003. These types of source provide new information about the nature and depth of Irish–Indian connections.

Although Giri takes centre stage in this study, to position him thusly is to read history backwards. While in Dublin, his greatest achievements were yet in front of him and he represented just one among fifty Indian students who studied between the King’s Inns and UCD in the years 1913–17. Prior to putting flesh on the bones of Giri’s compatriots, one methodological error to which I must confess is that I initially regarded Giri’s Indian classmates as a monolith. This was a false conception reinforced by archival sources which so often referred to these scholars as ‘Indian students’, ‘a number of students from Madras’, and in other such terms. Even in his memoir, Giri is guilty of conflating the ‘I’ and the ‘we’ when referring to the actions of himself and his comrades. What became clear once I began to extract personalities from the list of names before me was the point which should have been obvious from the beginning, that in these fifty students held at least as many different outlooks. I began to account for the seeming incongruities between the stances of one and another anonymous Indian author appearing in the various contemporary Dublin newspapers and magazines. Through this, I realised the diversity of opinion existing among Dublin’s small Indian student community. Ranging from reformers to radicals, these students held a wide cross-section of opinions. What did unite them was the need to act collectively to overcome some of the challenges they faced in Dublin. Beginning with administrative obstacles and the conservativism of members of the educational establishment and concluding with the fears over their being singled out among Dublin’s citizenry, the experience of Indian students in Dublin was not without its challenges.

This book is thus as much a study of students and migration as it is one about Irish–Indian relations. The issues and problems it considers echo the questions about student activism and the difficulties of assimilation and the isolation faced by minority ethnic student communities across European cities in the same period. The longer history of Indian students in Britain and Ireland opens revealing insights, especially into the attitudes of host communities where everything from housing, moral crises, inter-racial relations, political subversion, intelligence gathering and political violence come under the spotlight. These same tropes emerge in Goetz Nordbruch’s study of Arab students in Weimar Germany and Thomas Weber’s Our Friend ‘The Enemy’: Elite Education in Britain and Germany before World War I.2 Similar issues can be found in older studies on the experience of African students in the USSR, Filipino students in 1940s Chicago, and even the reaction to American (male) students in Paris during and directly after the First World War.3

Antoinette Burton has done important work in challenging the conception ‘that the phenomenon of colonial “natives” in the [British] metropole is a twentieth century phenomenon from which the Victorian period can be hermetically sealed off.’4 Early twentieth-century Dublin, although by no means as culturally diverse as London and British port cities such as Liverpool and Southampton, is nonetheless another example of a city in which the ethnic diversity of the metropolis has not been fully incorporated into general narratives by historians.5 While fictional non-natives such as Leopold Bloom have earned their place in Irish public perceptions of the past, real-world analogues such as the Jewish solicitor Michael Noyk, who moved to Ireland in 1908 and became a trusted friend and confidante of advanced nationalists including Arthur Griffith, have been less readily embraced in the grand narrative of Irish history.6

The students under consideration here are those who came to study at University College Dublin, an institution in its infancy in this period. Building on an educational tradition which stretched back to the 1850s, UCD was still in the process of asserting and articulating its identity as the ‘national’ university when its first influx of international students applied to enter in the autumn of 1913. UCD was the successor to the ‘University College’ of the Royal University of Ireland (1882–1908) and, before that, the Catholic University founded by Cardinal John Henry Newman in 1854.7 University College was re-constituted in 1908 with the passage of the Universities (Ireland) Act. The Act established a new National University of Ireland, replacing the old Queen’s Colleges of Cork, Galway and Maynooth as well as the Royal University of Ireland, alma mater to James Joyce and other notable alumni of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Additionally, the Universities (Ireland) Act established a second new university, Queen’s University Belfast, which descended from the former Queen’s College there.

Returning to Dublin, the newly constituted UCD stood on the site of its predecessor but the organisational structure of the university had been changed dramatically. New professorships and faculties were established and the ‘national’ character of the new university was asserted in subjects such as history and the Irish language. In an important change in the new university, the Irish language also became a requisite subject for matriculation. This condition of entry lent a distinctive nationalistic character to the new university. Enthusiasm for the Irish language tended to be strong among those of a nationalist political persuasion. Before the radicalisation and transformation of Irish politics that occurred in the latter half of the First World War, the student body of UCD was, like the majority of Irish society, largely supportive of the peaceful and constitutional Irish Home Rule movement which boasted consistent control over roughly three-quarters of Ireland’s 103 seats in the House of Commons between 1885 and 1918. Among the new university’s staff the Professor of National Economics, Tom Kettle, and the Professor of Constitutional Law and the Law of Public and Private Wrongs, John Gordon Swift MacNeill, were both Home Rule MPs in this period.8

In spite of the prevailing dominance of orthodox nationalist politics in UCD, between 1913 and 1914, the fledgling university also produced new militant movements. While ideologically loyal to the Home Rule tradition, these individuals and groups inaugurated a radical departure from constitutionalism in their tactics. In November 1913, Eoin MacNeill, Professor of Early (including Mediaeval) Irish History, became the leader of a newly founded paramilitary organisation, the Irish Volunteers. The force was pledged to the defence of Irish Home Rule. In April of 1914, MacNeill’s initiative was followed up by his colleague, Agnes O’Farrelly, lecturer, and later professor, of Irish at UCD. O’Farrelly was a leading founding member of Cumann na mBan, the women’s auxiliary to the Irish Volunteers. Both the men’s Irish Volunteers and the women’s Cumann na mBan trained their members in the use of arms. Although the university itself was keen to show its support for the war effort after Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, individual members of the college staff were heavily involved in more radical politics. In April 1916, an insurrection broke out in Dublin and an Irish Republic was proclaimed; the University found itself in the unusual situation of having to formulate a response to the fact that several of its staff had been arrested for their role in the rebellion.9 Among the leadership of the rebellion was Thomas MacDonagh, assistant lecturer in English at UCD and commandant of the 2nd Dublin Battalion of the Irish Volunteers. As a signatory of the document proclaiming the Irish Republic and as commander of one of the rebel garrisons, MacDonagh was among fourteen executed in Dublin following the surrender of the self-proclaimed provisional government.

As to the student body in UCD, taking the figures for 1915, there were 946 students in total: 722 men and 224 women. The largest faculties were Arts-Science-Commerce, which had an enrolment of 437, and Medicine which – even with the diminution of student numbers during the First World War – had 292 students.10 The Law faculty in 1915 numbered sixty-six students of whom only one was a woman, women being ineligible to membership of the Honourable Society of King’s Inns at the time thus precluding them from practicing law as barristers.11 Of these sixty-six, thirty-four were studying for a full degree course in Law at UCD while the other forty-nine, including twenty-four Indian students, were attending lectures at UCD for the period of a year in order to fulfil the requirements of the King’s Inns which conferred and governed membership of the outer and inner Bars of Ireland.12 This, the highest year of Indian enrolment at UCD, saw Indian law students constituting more than a third of all law students and just less than half of the ‘other’ law students at UCD.

These Indian students also undertook legal studies in order to qualify for the Bar at the Honourable Society of the King’s Inns, Dublin. A much older institution than UCD, the Honourable Society of King’s Inns had been established in 1541 and had moved to the site it presently occupies on Constitution Hill in the 1790s. Up until 1867, the King’s Inns catered for barristers, solicitors, attorneys and law students. However, from 1868 onwards, it only represented the barrister profession and students wishing to be called to the Bar.13 Up until 1885, students studying to be called to the Irish Bar were obliged to reside at one of the four English inns of court at London as a prerequisite to qualification.14

In a final note, while this restriction had been lifted prior to the period during which Indian students travelled to Dublin to study at the King’s Inns, one other major reform was yet on the horizon. Whereas both UCD and TCD were open to female students by 1913, the King’s Inns maintained a strict gender bar. The Benchers, who acted as the governing body of the King’s Inns, were resistant on this front. Ultimately, external legislation changed the regime at the Inns and the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act (1919) facilitated the entry of women students. The first woman to be called to the Irish Bar was Frances Christian Kyle, who was called in November 1921.15 While Indian students were arriving at King’s Inns in the autumn of 1913, the Irish Womens’ Reform League wrote to the Benchers requesting that a deputation be received to appeal to the Society to admit women. The Benchers informed the Under-Treasurer of the Society to acknowledge the correspondence received ‘and to inform the League that the law does not allow women to become students or Barristers-at-Law, and that as no good purpose would be served by receiving a deputation the Benchers must decline according to the request’.16 At a time when the first large-scale influx of Indian students was occurring at the King’s Inns, it is interesting to see the resistance of the Society to a further diversification of the student body.