Читать книгу Little Princes: One Man’s Promise to Bring Home the Lost Children of Nepal - Conor Grennan - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter One

THE BROCHURES FOR VOLUNTEERING in Nepal had said civil war. Being an American, I assumed the writers of the brochure were doing what I did all the time—exaggerating. No organization was going to send volunteers into a conflict zone.

Still, I made sure to point out that particular line to everybody I knew. “An orphanage in Nepal, for two months,” I would tell women I’d met in bars. “Sure, there’s a civil war going on. And yes, it might be dangerous. But I can’t think about that,” I would shout over the noise of the bar, trying to appear misty-eyed. “I have to think about the children.”

Now, as I left the Kathmandu airport in a beat-up old taxi, I couldn’t help but notice that the gate was guarded by men in camouflage. They peered in at me as we slowed to pass them, the barrels of their machine guns a few inches from my window. Outside the gate, sandbagged bunkers lined the airport perimeter, where young men in fatigues aimed heavy weapons at passing cars. Government buildings were wrapped in barbed wire. Gas stations were protected by armored vehicles; soldiers inspected each car in the mile-long line for gas.

In the backseat of the taxi, I dug the brochure out of my backpack and quickly flipped to the Nepal section. Civil war, it said again, in the same breezy font used to describe the country’s fauna. Couldn’t they have added exclamation points? Maybe put it in huge red letters, and followed it with “No lie!” or “Not your kind of thing!” How was I supposed to know they were telling the truth?

As we bounced along the potholed road, I turned longingly to the other opportunities in the volunteering brochure, ones that offered a six-week tour of duty in some Australian coastal paradise, petting baby koalas that were stricken—stricken!—with loneliness. I never could have gotten away with that. I needed this volunteering stint to sound as challenging as possible to my friends and family back home. In that, at least, I had succeeded: I would be taking care of orphans in one of the poorest countries in the world. It was the perfect way to begin my year-long adventure.

Nepal was merely the first stop in a one-year, solo round-the-world trip. I had spent the previous eight years working for the EastWest Institute, an international public policy think tank, out of their Prague office, and, later, the Brussels office. It had been my first and only job out of college, and I loved it. Eight years later, though, I was bored and desperately needed some kind of radical change.

Luckily, for the first time in my life, I had some real savings. I was raised in a thrifty Irish-American household; living in inexpensive Prague for six years allowed me to save much of my income. Moreover, I was single, had no mortgage or plans to get married or have kids any time in the next several decades. So I decided— rather quickly and rashly—to spend my entire net worth on a trip around the world. I couldn’t get much more radical than that. I wasted no time in telling my friends about my plan, confident that it would impress them.

I soon discovered that such a trip, while sounding extremely cool, also sounded unrepentantly self-indulgent. Even my most party-hardened friends, on whom I had counted to support this adventure, hinted that this might not be the wisest life decision. They used words I hadn’t heard from them before, like “retirement savings” and “your children’s college fund” (I had to look that last one up—it turned out to be a real thing). More disapproval was bound to follow.

But there was something about volunteering in a Third World orphanage at the outset of my trip that would squash any potential criticism. Who would dare begrudge me my year of fun after doing something like that? If I caught any flak for my decision to travel, I would have a devastating comeback ready, like: “Well frankly Mom, I didn’t peg you for somebody who hates orphans,” and I would make sure to say the word orphans really loudly so everybody within earshot knew how selfless I was.

I looked out the dirty taxi window. Through the swarm of motorcycles and overcrowded buses, I saw a small park that had been converted into a base for military vehicles. Some children had gotten through the barbed wire fence and were playing soccer. The soldiers merely watched them, hands resting on their weapons. I took a last look at the photo of the lonely koalas, sighed, and put the brochure away. In two and a half months I would be far away from here, preferably on a conflict-free beach.

After a half hour of driving through choking traffic over a pockmarked slab of highway known as the Kathmandu Ring Road, then through a maze of smaller streets, I noticed the scene outside had changed. Moments earlier it had been a chaotic mass of poverty and pollution; this new neighborhood was almost peaceful in comparison. There were very few cars, save the occasional taxi. The shops had changed from selling household necessities like tools and plastic buckets and rice to selling more expensive, tourist-oriented things like carpets, prayer wheels, and mandalas, the beautifully detailed paintings of Buddhist and Hindu origin used by monks as a way of focusing their spiritual attention. Vendors leaned in the window as my taxi edged its way through them, offering carvings of elephants or wooden flutes or apples perched precariously on round trays. Bob Marley blared out of tinny speakers.

The biggest change was that the pedestrians were now overwhelmingly white. They fell into two broad categories: hippies in loose clothing, with beaded, kinky hair, or sunburned climbers in North Face trekking pants and boots heavy enough to kick through cinder blocks. There were no soldiers to be seen. We had arrived in the famed Thamel district.

There are really two Kathmandus: the district of Thamel and the rest. In the general madness of Nepal’s capital, Thamel is a six-block embassy compound for those who want to drink beer and eat pizza and meat that they pretend is beef but is almost certainly yak or water buffalo. Backpackers and climbers set up camp here before touring the local temples or hiking into the mountains for a trek or white-water rafting. It is safe and comfortable, with the only real danger being that the street vendors may well drive you to lunacy. It was like the Nepal that you might find at Epcot Center at Disney World. I finally felt at ease. I would spend my first hours in the Thamel district, and by God I was going to enjoy it.

Orientation for the volunteer program began the next day, held at the office of the nonprofit organization known as CERV Nepal. I sat with the other dozen volunteers, mostly Americans and Canadians, and tried to focus on the presentation. The presenter was speaking in slowly enunciated detail about Nepalese culture and history. The presentation was frightfully boring. I found it impossible to keep my attention focused on the speaker, even when I concentrated and dug my nails into the palms of my hands. By the second hour, I would hear phrases like “Remember, this is Nepal, so whatever you do, try not to—” and then notice a leaf flittering past the window and get distracted again.

That changed about an hour and a half into the presentation when the entire group visibly perked up at the mention of the word toilet.

Travel to the developing world and you will quickly learn that toilets in the United States are the exception rather than the rule. I readily admit to my own cultural bias, but to me, toilets in America are the Bentleys of toilets, at the cutting edge of toilet technology and comfort, standing head and shoulders above what appeared to be the relatively primitive toilets of South Asia. Unfortunately, those toilets are often first discovered at terribly inopportune moments, sometimes at a full run after eating something less than sanitary, bursting through a restroom door to discover a contraption that you do not quite recognize. If there is ever a moment for panic, that is the moment.

So when I heard Deepak say “You may have noticed toilets here are different” my ears twitched. Deepak then took a deep breath and said, “Hari will now demonstrate how to use the squat toilet.”

I wondered if I had heard that correctly.

Hari walked to the middle of the circle of suddenly alert volunteers. Jen, a girl from Toronto sitting a few feet away, summed up what everybody must have been thinking with a panicked whisper: “Is he gonna crap in the room?”

Hari reached for his belt. I heard somebody shout “Oh no!” but I couldn’t take my eyes off the nightmare unfolding in front of me.

But wait—he was only miming undoing his belt. He then mimed lowering his trousers, mimed squatting down, mimed whistling for a few seconds, then mimed using an invisible water bucket to clean the areas that shall not be named. He stood up and gave a little “voilà!” flourish, then quickly left the circle and walked past Deepak out the door, his face bright red.

Clearly Deepak outranked Hari.

I wanted to applaud. It was the first truly practical thing we’d learned. For months afterward, I often thought of Hari at those precise moments, and I silently thanked him every time I watched a hapless tourist step into a bathroom and saw their brow furrow as the door closed behind them.

The in-office orientation lasted just one day, and then we piled into the backs of old 4x4s and drove south out of Kathmandu toward the village of Bistachhap, where we would continue our week-long orientation. We would be placed with families, one volunteer per home, to get acclimated to village life in Nepal.

Bistachhap is a tiny village on the floor of a valley surrounded by what I would have called mountains back in the United States, rising about two thousand feet above the village. With the Himalaya in the background, though, they looked like good-sized hills. These hills formed the southern wall of the Kathmandu Valley. The valley floor was covered with rice paddies and terraced mustard fields, blooming in bright yellow. Bistachhap itself was little more than a small collection of about twenty-five homes, mostly mud but some concrete, a dirt path connecting them like the wire on a set of Christmas lights. The houses sat on the north side of the floor of the valley, each one providing a view of the rice paddies on the other side of the path. I was assigned to a concrete yellow house, which looked pretty snazzy sitting next to the mud ones, though inside revealed a simple structure. I had my own bedroom, a simple affair with a single bed on a mattress of straw and a swatch of handmade carpet spread out on the floor. It was clear that somebody else in the house had vacated their room for me.

After dropping my backpack in the room, I went to formally introduce myself to my host mother, proud to be able to use one of the three expressions I had learned in Nepali: “Mero naam Conor ho.” My host mother, in the middle of her workday, was caught off guard by my apparent comprehension of her language. She dropped her water bucket and raised her hands over her head in excitement and launched into a monologue about God knows what. I took a step back and held up my hands, saying “Whoa whoa whoa whoa!” for the entire time she spoke. In Nepali that must mean “Continue! I completely understand you, and I enjoy this conversation!” because damn if she didn’t go on for several minutes, getting more and more excited, until her daughter, a little girl of perhaps six or seven, took my hand and dragged me away.

The daughter, whose name I would learn was Susmita, walked me out to the front porch and plopped down on a straw mat, inviting me to do the same. She pointed to the mat and said a word in Nepali, waiting for me to repeat it. I did so. Then she repeated this with the house, the door, the garden, and anything else she could think of. I repeated each word and let her correct me until I had nailed it. Her face lit up. She was going to teach me Nepali, and I was going to learn. She disappeared, returning a few moments later with her homework, wherein she drew a single character in Sanskrit over and over, as one might practice a capital B, pointing to each one for my benefit until her mother fetched her to help with dinner preparation.

Unsure of what to do, as I could see no other volunteers anywhere, I took a walk through the village. I called out “Namaste!” to every villager I passed, and usually received a “Namaste” in return, though they seemed oddly reluctant.

This turned out to be, not surprisingly, my own fault. I had thought “Namaste” was like “Hey there!” or “What’s up?” but I would later learn that it was a far more formal greeting than this. Yoga enthusiasts will recognize it and may even know the translation, which is along the lines of “I salute the God within you.” Heavy stuff. Yet I yelled it to everybody, the same way you might yell “Dude!” or “My man!” to your buddies. I accompanied it with a big friendly wave. I said it to children. I said it to people I’d just seen four minutes earlier. I saw a stray dog and bent down to give him a scratch behind the ears and saluted the God within him. I saluted the God within a mother carrying a baby, then saluted the God within the baby.

Down the path, I saw my host mother outside looking around for me. She recognized me from a distance and waved me in. I was late for dinner. I followed her into what I supposed was the kitchen. There was a mud floor, an open fire in the corner, and two boys of perhaps nine years old sitting Indian style on the floor next to Susmita, who sat next to their father. The boys patted the ground next to them happily, pleased that I was joining them. The mother, meanwhile, had squatted next to the large pot. She picked up a metal plate and dumped what looked like several pounds of rice onto it for the family, and placed it in front of me. I was about to take some and pass it along, when I saw her preparing an even bigger mountain of rice and placing it in front of the father.

After placing similar plates in front of her children, she took a ladle out of the other pot and poured steaming hot lentil soup over the rice on our plates: daal bhat, literally, “lentils with rice.” Daal bhat is eaten by about 90 percent of Nepalese people, twice a day. The mother added some curried vegetables to my plate, at the same time shooing away a stray chicken.

When everyone was served, the mother put her hand to her mouth, indicating that I should eat. I nodded in thanks, then looked around for some kind of utensil. There was no utensil. I watched the rest of the family stick their hands into the hot goo, mash it up, and begin shoveling it into their mouths.

After maybe half a minute watching my host family eat, my jaw hanging slack near my collarbone, I noticed that they had stopped eating, one by one, and were staring at me, wondering why I wasn’t eating. I came to my senses. I had been with my host family for all of ten minutes and was on the verge of causing some irrevocable offense. I forced a smile, took a chunk of rice and daal and a smidge of some kind of pickled vegetable, and placed it gently into my mouth.

It was spicy. Spicy in the way that your eyes instantly flood with tears and your sinuses feel like the last flight of the Hindenburg, as if somebody inside my skull had ordered a full evacuation. The children started giggling. Even the chicken stopped pecking to watch what would happen next.

What happened next was that I opened my mouth to breathe, but the back draft only fanned the flames in my throat. I grasped for the tin cup of water next to me, oblivious to the shouts of the father, mother, and three children, and realized, too late, that my hand was burning because the water in the tin cup was still boiling.

I opened my mouth and let out a kind of “Mwaaaaaaa” sound, very loudly, and used my hands, so recently used as eating utensils, to fan myself, spraying a light mist of rice and lentils into my face and hair. I opened my eyes to see the family trying to decide if I needed assistance, and if so, what that assistance might look like.

You can’t go through that experience with a family and not become closer. The older of the two boys, whose name I learned was Govardhan, had a Nepali-English phrasebook with him, and we had the most basic of conversations, the one where you say Nepal is beautiful, then, because this is a phrase that I apparently got right, they began asking if the house was beautiful, if the mountains were beautiful, if the chicken was beautiful, if their mother’s hair was beautiful, and so on until everybody had finished their pile of rice.

I had eaten as fast as I could through all this; my stomach felt like I’d swallowed a bag of sand. I looked down to see that I had made it through just over a third of my food. I pointed at the rice and told the mother that the rice was truly beautiful, but that my stomach (I pointed at my belly button) was not beautiful. She laughed and with a wave of her hand excused me. I waved a good night “Namaste!” and headed up to my room.

I walked outside later to brush my teeth from the water bucket, as there was no running water. I was careful not to swallow any. I brushed slowly under the thick coat of stars. The quiet was absolute. The neighbors’ homes were lit by candles, with an occasional lightbulb shining in the windows of the wealthier houses. I could just make out another volunteer two houses down, also brushing his teeth using an old water bucket, also staring straight up at the stars, and maybe also wondering if he was really here, if he was really standing on the opposite side of the planet from his home. This was one of those moments I wanted to capture, to hold on to and to stare into like a snow globe. This world was already completely different from anything I had ever experienced—and this was just day one.

The immersion week was useful in getting us at least partially accustomed to this strange new culture. The most valuable part of it was practicing Nepali with Susmita. She made sounds slowly, pointing at pictures, and I repeated them. When I tried to show off my knowledge of animal names for the rest of the family on my final night in Bistachhap, they frowned and consulted each other, trying to work out what I was saying.

Finally I took Govardhan out behind the house, next to the outhouse, and pointed at the goat. I said my word, which sounded like “Faalllaaaagh.” He shook his head: “Hoina, hoina,” he said, which I knew meant “no.” He pointed at the goat. “Kasi,” he said.

Kasi? That sounded nothing like faalllaaaagh. Had I gotten the wrong animal?

“Who say?” Govardhan asked in English. It was the first English he had spoken.

I told him Susmita, his little sister, had told me. His eyes popped wide, and he literally doubled over laughing and ran in to tell his family. I discovered later that Susmita, my lovely little teacher, was deaf.

HARI, OF TOILET-MIMING FAME, picked me up from Bistachhap in the jeep and threw my backpack in the back. He pointed across the valley.

“That is Godawari,” he said, pronouncing it go-DOW-ry. “That is where you will be volunteer. I will see you very often there—I work there also. I am part-time house manager for the orphanage where you go.”

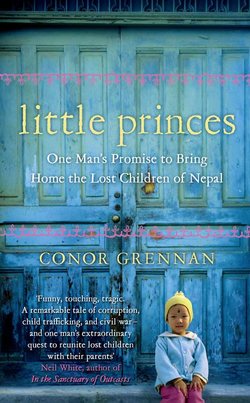

I had seen the house from a distance during a trek up one of the large hills, but I knew little about it. The orphanage was called the Little Princes Children’s Home, named after the French novella by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince. It had been started by a French woman in her late twenties.

I nodded and made a vague comment about how excited I was to get started. But my mind was elsewhere. It would be two weeks before I would actually show up for orphan duty; before that, I would be fulfilling my dream of trekking to Everest Base Camp. I had been moved by Jon Krakauer’s harrowing account of climbing Mt. Everest in a storm in 1996, on a day when eight climbers perished. The summit of the world’s tallest mountain is just shy of thirty thousand feet—the cruising altitude of a Boeing 747. I would never in my life have the strength to climb the mountain, but I was dying to see it. When I learned that Everest was in Nepal (a country that I had previously confused with Tibet), I decided it was the perfect country to volunteer in—I could combine my volunteering experience with a trek to Base Camp. I was in good physical condition, so it wasn’t as if I was going to keel over from altitude sickness. I couldn’t wait to get started.

WHEN I WASN’T LYING on the side of the trail, winded and dry-heaving from altitude sickness, I managed to take a lot of photos. There was no shortage of things to photograph: the trek up to Base Camp was spectacular. Every step is a step skyward, through simple Buddhist villages that seem to be glued to the sides of impossibly tall mountains. The Sherpa people are native to that region, having come over the mountains from Tibet hundreds of years earlier. They are traditionally Buddhist. In every village you could see carved oversized Sanskrit prayers chiseled into boulders and blackened, like tattoos. Trekkers were expected to walk to the left of these Mani Stones, clockwise, to respect the faith of the local community.

With the extraordinary Himalayas taking up most of the sky, it was difficult to keep an eye on the trail. Yet keeping an eye on the trail was essential to survival. Enormous, shaggy yaks, laden with hundreds of pounds of climbing gear, would come barreling down the trail, seeming not to notice humans at all. The first few I saw were a novelty, but after that we loathed them as dangerous pains in the ass.

But there were bigger dangers. In the village of Lukla, the start and end point of the Everest Base Camp trek, a few dozen soldiers manned an outpost. Everest National Park (known in Nepal as Sagarmatha National Park) was one of the few regions left in Nepal over which the royal government claimed control, but even that was under constant threat by Maoist rebels who controlled the surrounding area. As I waited for a small plane to take me back to Kathmandu, sirens blared and soldiers ran past the door of the tea shop, automatic weapons in hand. There was no fighting, and I got the impression that it may have all been a drill. But when I got back to Kathmandu, I decided I had seen just about enough of the rest of this country. The Kathmandu Valley was safe from rebel attack; I wouldn’t leave again for the duration of my three-month stay in Nepal.

I HAD ONE FULL day to relax in the Thamel district of Kathmandu. But there was no more putting it off. I reported for duty the next day at the CERV office.

“We’re ready to go—are you excited?” Hari asked.

“I sure am!” I practically shouted, because I believed that to be the only answer I could give without sounding like I was having second thoughts about this whole orphanage thing.

We drove to the village of Godawari. It was only six miles south of Kathmandu, but it felt like a different world. Inside Kathmandu’s Ring Road, people, buildings, buses, and soldiers were all crammed into a small space. There was almost nothing peaceful about the city. But outside the Ring Road, the world opened up. Suddenly there were fields everywhere. The roads disappeared, save for the single road that led south to Godawari, which ended at the base of the hills that surround the Kathmandu Valley. The air was cleaner, people walked slower, and I started to see many homes made of hardened mud.

When the paved road ended, we turned onto a small dirt road and took it a short distance. Hari stopped in front of a brick wall. There was a single blue metal gate leading into the compound. He lifted my backpack out of the back, and held it while I put it on, strapping the waist buckle. With a hearty handshake, he bade me farewell, wished me luck, and climbed back into the jeep. He backed out the way we had come in.

I watched Hari drive away, then turned back to the blue metal gate that led into the Little Princes Children’s Home.

I hadn’t realized until that moment how much I did not want to walk through that gate. What I wanted was to tell people I had volunteered in an orphanage. Now that I was actually here, the whole idea of my volunteering in this country seemed ludicrous. This had not been lost on my friends back home, a number of whom had gently suggested that caring for orphans might not be exactly what God had in mind for me. They were right, of course. I stood there and tried to come up with even a single skill that I possessed that would be applicable to working with kids, other than the ability to pick up objects from the floor. I couldn’t recall ever spending time around kids, let alone looking after them.

I took a deep breath and pushed open the gate, wondering what I was supposed to do once I was inside.

As it turns out, wondering what you’re supposed to do in an orphanage is like wondering what you’re supposed to do at the running of the bulls in Spain—you work it out pretty quickly. I carefully closed the gate behind me, turned, and stared for the first time at a sea of wide-eyed Nepali children staring right back at me. A moment passed as we stared at one another, then I opened my mouth to introduce myself.

Before I could utter a word I was set upon—charged at, leaped on, overrun—by a herd of laughing kids, like bulls in Pamplona.

THE LITTLE PRINCES CHILDREN’S Home was a well-constructed building by Nepalese standards: it was concrete, had several rooms, an indoor toilet (huzzah!), running water—though not potable—and electricity. The house was surrounded by a six-foot-high brick wall that enclosed a small garden, maybe fifty feet long by thirty feet wide. Inside the walls, half the garden was used for planting vegetables and the other half was, at least in the dry season, a hard dirt patch where the children played marbles and other games that I would come to refer to as “Rubber Band Ball Hacky Sack” and “I Kick You.”

All games ceased immediately when I stepped through the gate. Soon I was lugging not only my backpack but also several small people hanging off me. Any chance of making a graceful first impression evaporated as I took slow, heavy steps toward the house. One especially small boy of about four years old hung from my neck so that his face was about three inches from my face and kept yelling “Namaste, Brother!” over and over, eyes squeezed shut to generate more decibels. In the background I saw two volunteers standing on the porch, chuckling happily as I struggled toward them.

“Hello!” cried the older one, a French woman in her late twenties who I knew to be Sandra, the founder of Little Princes. “Welcome! That boy hanging on your face is Raju.”

“He’s calling me ‘brother.’ ”

“It is Nepalese custom to call men ‘brother’ and women ‘sister.’ Didn’t they teach you that at the orientation?”

I had no idea if they had or not. “I should have put down my backpack before coming in,” I called back, panting. “I don’t know if I can make it to the house.”

“Yes, they are really getting big, these children,” she said thoughtfully, which was less helpful than “Children, get off the nice man.” One boy was hanging by my wrist, calling up to me, “Brother, you can swing your arms, maybe?”

I collapsed onto the concrete porch with the children, which initiated a pileup. I could see only glimmers of light through various arms and legs. It was like being in a mining accident.

“Are they always this excited?” I asked when I had managed to squirm free.

“Yes, always,” said Sandra. “Come inside, we’re about to have daal bhat.”

I went upstairs to put my stuff down in the volunteers’ room, trailed by several children. We were five volunteers in total. Jenny was an American girl, a college student, who had arrived a month earlier. Chris, a German volunteer, would arrive a week later. Farid was a young French guy, thin build and my height, twenty-one years old, with long black dreadlocks. I first assumed Farid was shy, since he was not speaking much to the others, but soon realized that he was only shy about his English.

I was the last to arrive for daal bhat. I entered the dining area, a stone-floored room with two windows and no furniture save a few low bamboo stools reserved for the volunteers. The children sat on the floor with their backs against the wall, Indian style. They were arranged from youngest to oldest, right to left against three walls of the room. As they waited patiently for their food to be served, I got my first good look at them.

I counted eighteen children in total, sixteen boys and two girls. Each child seemed to be wearing every stitch of clothing he or she owned, including woolen hats. I had not worn a hat to dinner and was already regretting it. The house had no indoor heating and I could practically see my breath. Most of their jackets and sweaters had French logos on them, as the clothes were mostly donations from France. I studied their faces. The girls were easy to identify, as there were only two of them, but the boys would be more difficult to distinguish. A few really stood out—the six-year-old boy with the missing front teeth, the boy with the Tibetan facial features, the bright smile of another older boy, the diminutive size of the two youngest boys in the house. But otherwise, the only identifying features to my untrained eye would be their clothes.

Before daal bhat was served, Sandra asked the children to stand and introduce themselves, beginning with the youngest boy, Raju. He was far more shy now than when he had been clinging to my face. The other boys whispered loud encouragements to him to get up, and his tiny neighbor, Nuraj, dug an elbow into his ribs. Finally he popped up, clapped his hands together as if in prayer, the traditional greeting in Nepal, said “Namaste-my-name-isRaju” and collapsed back into a seated position flashing a proud grin to the others. The rest of the kids followed suit, until it had come full circle back to me.

I stood up and imitated what they had done and sat back down. They erupted in chatter.

“I do not think they understood your name,” Sandra whispered to me.

“Oh, sorry—it’s Conor,” I said, speaking slowly. I could hear a volley of versions of my name lobbed back and forth across the room as the children corrected one another.

“Kundar?”

“Hoina! Krondor ho! Yes, Brother? Your name Krondor, yes?”

“No, no, it’s Conor,” I clarified, louder this time.

“Krondor!” they shouted in unison.

“Conor!” I repeated, shouting it.

“Krondor!”

One of the older boys spoke up helpfully: “Yes, Brother, you are saying Krondor!”

Trust me—I wasn’t saying “Krondor.” The children were staring earnestly at my lips and trying to repeat it exactly.

“No, boys—everybody—it’s Conor!” This time I shouted it with a growl, hoping to change the intonation to a least get them off Krondor, which made me sound like a Vulcan.

There was a surprised pause. Then the children went nuts. “Conor!!” they growled, imitating the comical bicep flex I had performed (instinctively, I’m sorry to say) when I shouted my name.

“Exactly!” I said, pleased with myself.

Sandra looked around and nodded in approval. “I think you will get along with these children very well,” she predicted. “Okay, children, you may begin,” she said, and the children attacked their food as if they hadn’t eaten in days. They spent the rest of dinner with mouths full of rice and lentils, looking at each other and growling “Conor!!!” flashing their muscles like tiny professional wrestlers.

There was no way to keep up the blistering pace set by the kids when they ate. They had literally licked their plates clean when I was maybe half finished. I would have to concentrate in the future. No talking, no thinking, just eating. There was far too much food on my plate, albeit mostly rice. The worst part about it was that I couldn’t give the rest of mine away, since once you touched your food with your hands it was considered juto, or unclean, to others. The very idea of throwing away food here was unthinkable, especially with eighteen children watching you, waiting for you to finish. I force-fed myself every last grain as fast as I could, guiltily replaying scenes from my life of dumping half-full plates of food into the trash.

When I had finished, Sandra made a few announcements in English. The children understood English quite well after spending time with volunteers, and the little ones who didn’t understand as well had it translated by the older children sitting near them.

The big announcement of that particular evening was the introduction of three new garbage cans that had been placed out front, one marked “Plastic and Glass,” one “Paper,” and one “Other.” Sandra explained their fairly straightforward functions. She was rewarded with eighteen blank stares. Trash in Nepal, like all Third World countries, is a constant problem. Littering is the norm, and environmental protection falls very low on the government’s priority list, well below the challenges of keeping the citizens alive with food and basic health care. Farid took a stab at explaining the concept of protecting Mother Earth, but the children still struggled to understand why anybody would categorize garbage.

“Maybe we should demonstrate it?” I suggested.

Sandra smiled. “That is a great idea. Go ahead, Conor.”

This was a big moment. I had never interacted with children before in this way; I had no nieces, no nephews, no close friends with children, no baby cousins. I steeled myself for this interaction. Fact: I knew I could talk to people. Fact: Children were little people. Little, scary people. I took solace in the fact that if this demonstration went horribly wrong, I could probably outrun them.

“Okay, kids!” I declared, psyching myself up. I rubbed my hands together to let them know that fun was on the way. “Time for a demonstration!”

I picked up a piece of paper leaning against my stool and crumpled it up. I walked over to Hriteek, one of the five-year-old boys, and handed it to him.

“Okay, Hriteek, now I want you to take this and throw it in the proper garbage can!” I spoke loudly, theatrically.

Hriteek took the paper in his little hand and held it for a few seconds, looking at the three green bins lined up with their labels visible. Then he started to cry. I hadn’t expected that. But I knew that kids sometimes cried—I had seen it on TV. This was no time to quit.

“C’mon, buddy,” I urged him. “It’s not tough—throw the trash in the right bin,” I said, nodding toward the “Paper” bin.

No luck. Finally I took it from him, giving him an understanding pat on the shoulder, and walked over to throw it in the proper bin.

“Brother!” called out Anish, one of the older kids sitting opposite us. “Brother—wait, no throw, he make for you! Picture!”

I uncrumpled the paper to discover a crude but colorful picture of a large pointy mountain and a man—me, judging by the white crayon he used for skin tone—holding hands with a cow. On the bottom it was signed in large red letters: hriteek. Uh-oh.

“Hriteek! Yes! Great picture! Not trash, Hriteek! Not trash!” I said quickly. He cried louder.

Sandra leaned over to me. “It’s no problem, Conor,” she said, and took Hriteek’s hand. “Hriteek, you do not need to cry. Conor Brother is still learning. He doesn’t understand much yet. You will have to teach him.” This brought a laugh from the children, and Hriteek, despite himself, started giggling.

“Sorry, Hriteek!” I said over Sandra’s shoulder. “My bad, Hriteek! Your picture was very beautiful, I’m keeping it!” I smoothed it out against my chest as Hriteek eyed me suspiciously.

“Okay, everybody,” Sandra said, clapping her hands. “Bedtime!”

The children leaped up, brought their plates to the kitchen, cleaned up, and marched up to bed. Anish, the eight-year-old who had informed me of my traumatic error, lingered in the kitchen to help wash the pots at the outdoor tap. By the time he finished helping clean up, the rest of the children had already gone up to their rooms. He lifted his arms to me to be carried upstairs. “We are very happy you are here, Conor Brother!” he said happily.

“I am very happy to be here, too,” I replied, stretching the truth to its breaking point. I was relieved, at least, to have the first day over with. I lifted Anish and carried him up the stairs.

That night, huddled in my sleeping bag wearing three layers of clothing plus a hat, I slept more soundly than I had in a long time. I was more exhausted than I’d been after trekking to the foot of Everest, and I’d only spent two hours with the children.

I WOKE THE NEXT day to the general mayhem of children sprinting through the house, half-crazed with happiness. I dove deeper into my sleeping bag and wondered what in human biology caused children around the world to take such pleasure in running as fast as they could moments after they had woken up. Unable to fall back to sleep, I nosed just far enough out of my bag to peek through the thin curtains. The sun had not yet risen above the tall hills behind the orphanage. The only source of heat in the village was direct sunlight, so I waited. At exactly 7:38 a.m. the sun flashed into the window. I got up and wandered downstairs.

Farid was sipping milk tea outside in the sun, his breath steaming in the morning chill. As I sat down next to him, a woman entered the gate, straining under the weight of an enormous pot, filled to the brim with what looked to be milk.

“Namaste, didi!” he called to her, lifting his tea in greeting. “She is our neighbor,” he explained. He had a thick French accent that took me a minute to get used to. “She brings milk every day from her cow for the children to put in their tea.”

“What did you call her? Dee-dee?”

“Didi. It means—do you speak French?”

“A little. Not very well I’m afraid,” I apologized.

“It is okay—I must improve my English, I know it is very bad,” he said. “So I saying? Ah yes—didi. It means ‘older sister,’ it is a polite way to greet a woman, as we might say madame or made-moiselle. The children call you ‘brother,’ yes?”

“Yeah.”

“In Nepali, they call older men dai—it means ‘older brother,’ but it is a sign of respect, like didi. We taught them the English word brother, so they use that.” He took a sip of his tea. “You know, it is quite useful, saying brother. It means you do not have to remember everybody’s name.”

That was useful, and prophetic. One of the boys came outside at that moment and plopped himself down on my lap.

“You remember my name, Brother?” he asked with a grin.

“Of course he remembers your name, Nishal!” Farid said. “Go get ready—we’re going to the temple soon for washing.”

I liked Farid immediately.

Going to the temple was, I learned, a Saturday tradition. Weekends in Nepal were one day only and the children savored them. Each Saturday they would begin the morning by cleaning the house together. The bigger boys would drag the carpets outside and the little boys would sweep with brooms made of thin branches tied together with twine. Then another group would finish by mopping the floor, which made the concrete at least wet if not exactly clean. Sandra told me that it was the act of the chores themselves that was valuable. If these children had been with their families, they would be tending to their homes and fields many hours per day.

With the house marginally less dirty, we walked to a nearby Hindu temple, a fifteen-minute stroll through the royal botanical gardens that happened to be just down the path from the orphanage, past the mud homes that made up the village of Godawari.

The temple was housed in a walled courtyard a little larger than a basketball court. Taking up half of that space was a shallow pool about three feet deep, constantly refilled by five spouts carved into the stone wall. Several villagers were already there, all men, leaning over to wash themselves under the spouts. (Washing at public taps, naked except for underwear, was the most common way of bathing. In Bistachhap, I had washed myself wearing only a pair of shorts at the single public tap in full view of the village, while local women waited patiently with a basket of laundry, giggling to one another and pointing at my pale skin.) Once finished, the men would dry off and go through a small gate in the back of the courtyard, where there was a grotto that housed the Hindu shrine. They would reemerge with a red tikka—rice with sticky red dye—on their forehead, then ring a large bell before leaving the temple.

The children obviously loved this place. They stripped down to their underwear, except for the two girls, Yangani and Priya, who watched from the sidelines. The boys dove in, splashing around and trying to dunk one another. One by one they would pop out and run to Farid, who would dole out a dollop of liquid soap to the older boys. The younger ones would wait patiently while Farid scrubbed them down himself. When they had completed that stage successfully, they ran to me, the Keeper of the Shampoo. Raju was the first to reach me. I squeezed a dose of shampoo the size of a quarter into his palm. His eyes grew wide at the apparently enormous pool of shampoo in his hand. I realized my mistake and started to take some back, but he sprinted back to the pool, yelling to his little friend Nuraj.

Farid noticed. “I think maybe a little less, Conor,” he said, thumb and index finger indicating a tiny amount. “I learned this lesson my first time also. You will see.”

Raju had rubbed the shampoo into such a thick lather that he looked like he was wearing a white afro wig. The others went bananas when they saw this, scrambling out of the pool and begging me for shampoo.

“I see what you mean,” I called over to Farid.

Farid shook his head, marveling at Raju. “They are very resourceful, these children,” he called back. “You will find they do very much with very little.”

After twenty minutes or so, the children began to exit the pool. One of the boys—maybe seven years old, with what I thought of as Tibetan facial features—approached me.

“Brother, where you put my towel?” he said, putting his hand on my knee and twisting his torso to scan the courtyard.

To identify the children, I had memorized the outfits of a few of them. They wore the exact same thing every day, as they only had two sets of clothes each. But now, this little brown body in front of me, clad only in his underwear, looked exactly like the other seventeen children.

“Uh . . . are you sure I had your towel, Brother?” I said slowly, buying time, hoping he might accidentally yelp out his own name. The word brother was going to save my life here.

The boy spun back to me and his hands went to his head. “Brother, you had one minute before! You say you take before I swim!”

Time for a stab in the dark. “Oh . . . right! Sorry, Nishal, I forgot, I put your towel over—”

“Nishal?! Ahhhh! I no Nishal, Brother!”

“I never said you were, Brother!”

“You say ‘Nishal’!”

“No, no, I said ‘towel.’ ” Didn’t you hear me say ‘towel’?” This blew his mind.

Farid walked up just at that moment. “Come on, Krish—we’ll find your towel,” he said, turning him around by his shoulders and leading him away. He turned back and gave me an empathetic little shake of the head, not to worry.

I sat down near the edge of the pool, trying to blend into the stone and praying no other children would come up to me. I felt a tap on my shoulder. Anish was standing there. I recognized Anish because his skin was slightly lighter than the others, he was quite tall for an eight-year-old, and he had a distinctively round face with a smile that curved sharply up at the edges, almost cartoonish.

“Brother, you no remember names,” he said. It was an observation rather than a question.

“Yes I do!” My protest was both instinctive and absurd, like a schoolboy in trouble.

Anish sat down next to me, facing the shallow pool where the boys were splashing around. He pointed at one of the boys.

“That is Hriteek. You know because he is always climbing,” he said. Sure enough, Hriteek, whose picture I had crumpled up the day before, was trying to climb the entrance gate. Anish pointed at another boy. “That is Nishal, looking like he will cry right now. With the towel is Raju, he is most small boy here. That is Santosh, the tall boy. . . .”

This lesson continued for the next ten minutes, Anish slowly drying on the flagstones in the hot sun, me beside him in the shade so I wouldn’t burn. When he had named all the boys and the two girls twice, he quizzed me on a few of them, all of whom I got wrong except for when he asked, slightly exasperated, if I knew his name.

“Yes! Anish!” I said proudly.

He smiled. “Okay, Brother. You pass,” he said, and went to get his clothes.

Soon everybody was out of the pool. Then it was laundry time for all the clothes that needed washing. The children had stuffed their clothes that needed washing in small plastic bags that they had found discarded around the village. When the plastic bags tore, the children would find tape and repair them. I thought of my local grocery store double-bagging a can of soda and felt another stab of guilt over my wastefulness.

The children carried their clothes across the path to where the water flowed out of the pool and down a two-foot-wide shallow canal to a stream. Working together, they used soap to scrub their pants and shirts. The youngest boys, Raju and Nuraj, didn’t have the arm strength to tackle such a project, so they concentrated on their little socks, laying them on the concrete and scraping them with a small chunk of soap. The orphanage had a woman who washed the boys’ clothes for them (a washing didi), but this was another way of teaching the children to take responsibility for themselves, of keeping them in as normal a life as possible considering they had been robbed of their families.

Back at the orphanage, the children hung their clothes to dry, then resumed their yelling and bouncing off each other. They had boundless energy. My own energy level was not nearly so high. But as luck would have it, the most popular game at Little Princes was a board game called carrom—or carrom board, as the children called it. The children (indeed, all of Nepal) were obsessed with this game. It is played on a square board with holes in the four corners. The object of the game is to flick a blue disc across the board at the black-and-white discs in an attempt to knock the discs into the holes. It’s like a cross between billiards and shuffleboard.

Every child in the house not only wanted to play this game, but they wanted to play it against me. I was first taught the rules by Santosh, who at nine years old was one of the older boys in the house.

“Look, Brother, you hit with your finger, yes, like this. See, I score, so is my turn again. And I hit again . . . and I score again, so my turn again. . . . And I score again, so my turn—”

“I get it, Santosh,” I interrupted.

“You try now, Brother!”

I flicked one of the discs, which ricocheted off the board. Santosh watched it fly past him and slide under the couch. Then he looked back at the board.

“Okay, Brother, you miss, so my turn again. . . . And I score, so my turn again.”

He beat me in six minutes flat; I had put up about as much fight as a loaf of bread. The children were eager to play me, not to see if they could win—they all won—but to time one another to see how quickly they could shut me out. The fact that I was trying as hard as I could to just score a single point was a severe blow to my ego. Nuraj was hardly even paying attention, and that little four-year-old ran the board on me.

I came closest to beating Raju. After initially refusing to play him a third time, citing a broken hand—it was the first excuse that came to mind—I finally played him only after he agreed to let me have the first fifteen shots in a row. I scored twice before Raju’s turn. He promptly scored continuously until all his discs had disappeared down the holes. The children gathered around for that match, jabbering away in Nepali. Anish leaned over to me.

“Brother,” Anish said in a loud, hoarse whisper that was louder than his normal speaking voice. “Everybody saying they never have seen Raju win this game before, Brother.”

“Thanks for that translation, Anish—that’s very helpful.”

“You are welcome, Conor Brother,” he whisper-yelled.

This loss was still fresh in my mind when Raju and Nuraj asked me to play Farmyard Snap. I felt like this was my chance to redeem myself. I smiled to myself when they challenged me, and told Raju to bring it on.

“What means ‘bring it on,’ Brother?”

“It means we can play.”

“Brother, remember I give you many many hits and I win you in carrom board, Brother? Very funny, yes, Brother?”

“Just get the cards, Raju.”

Farmyard Snap, as you may recognize from the name, is the same game as Patience, Memory, or Concentration. You turn the cards facedown, mix them up, and try to match the pairs. In this case, the pictures on the other side were of barnyard animals. It was a well-worn deck of cards, clearly used by other volunteers to help the children learn the English words for the various animals. English was an excellent skill for them to learn, and furthering the education of the children was one of the main reasons for being here. And as we laid out the cards, I tried to remind myself of that. Truly I did. But all I could think about was how badly I was going to crush these kids in Farmyard Snap.

I won the first game handily. To my slight disappointment, they both just laughed every time I uncovered a match, clapping for me as if they were letting me win. They even cheered for me when I won; Nuraj went out to tell some of the other boys like a proud father. When he returned I challenged them to a rematch to show my victory was no fluke.

“What means ‘rematch,’ Brother?”

“We play again—if you don’t mind me winning.”

“Yayyyyy!” they cried together.

Games two, three, and four didn’t go as planned.

Raju and Nuraj held a quick tête-à-tête following their loss in game one and decided they would play as a single team. I consented. Their game-time chatter sounded innocuous enough. It was unclear if they were even talking about the game at all, as I noted during one particularly animated debate between them, which ended when Nuraj put his entire fist in his mouth and Raju sullenly conceded some point. Still, I couldn’t trust them, and I was soon proven right. The cards were bent from extensive use, and they were able to push their little faces against the floor to see what was on the other side. Since they never actually touched the cards, I wasn’t able to penalize them, nor could I get my huge head low enough to see the other side myself—though I did try, which was a source of much amusement for them. They also pointed out to each other where the other donkey was, or where they remembered seeing the ducks. When it was my turn, they tried to distract me by loudly singing Nepali songs or climbing on my back and tugging on my hair. There was nothing in the Farmyard Snap rules against this per se, but it put me at a disadvantage that I was unable to overcome.

“Remash! Remash!” they chanted after the sixth game.

“I can’t—remember my broken hand?” I reminded them.

“Brother, I no think hand broken,” Nuraj said, poking at my hand.

“Let’s go find the other boys outside,” I suggested.

“Yayyyyy!”

The rest of the boys were playing soccer next to a nearby wheat field, and I sent the two little cheaters off to join them. Then I sneaked back to my bedroom and lay down, hoping for an early-afternoon rest. I leaned over to see my travel clock. It was only 10:30 a.m. I groaned and collapsed back on the bed.

I HAD FIRST ARRIVED at Little Princes when the children had a few days off from school. They returned to school only on Wednesday, four days later. That Wednesday will forever rank as one of the most peaceful days in my entire life. I took a walk through the village for the first time, along the single-track paths that led through the rice paddies and mustard fields, past the women working the fields, the men weaving baskets out of dried grass on their mud-hardened porches, the mothers carrying babies in slings as they washed their clothes at the public water tap. Everywhere I walked, people would stop what they were doing and watch me pass by. There was always time to stop what you were doing in Nepal—nobody punched a clock or tried to impress anybody else by working through lunch. They woke up, they worked until they had to prepare the fire to cook rice for dinner, then everybody came inside and ate before going to sleep. You wouldn’t find a soul outside after dark.

A week after I arrived, I walked into the children’s bedroom, expecting to help them get ready for school. Because they wore identical blue and gray school uniforms, the young ones needed some extra help in sorting out which pants belonged to whom. They also had trouble with their buttons and clipping on their little ties. The room was empty, so I went straight to the small cardboard box that said raju on the side of it to get a head start looking for his gray socks. The last two school days he had been unable to locate the pair; he was forced to wear one red sock and one gray sock, an event traumatic enough to leave him in tears. His sister, Priya, all of two years older than him but always dressed before anybody else, was by his side in an instant, holding his head as his tears stained her button-down shirt.

“It is okay, Brother, I talk to him,” she said, gently waving me away.

I had found one gray sock when a boy came flying down the stairs from the rooftop terrace and raced past the door. There was a screech of bare feet against the hard floor, and Anish poked his head into the room.

“What you look for, Brother?” he asked, puzzled.

“Raju’s socks . . . where is everybody?”

“No school today, Brother!” said Anish. “Today is bandha!”

“What’s a bandha?”

“No school, Brother! Come, we play on the roof! Come!” he took my hand and leaned his body weight toward the stairs for leverage.

I learned from Farid that a bandha was a Maoist-instigated strike. The Maoist rebels had been locked in a civil war against the monarchy in their bid to establish a People’s Republic of Nepal, to be founded on Communist principles. Bandhas were a common tactic used by the rebels, intended to bring the entire country to a standstill. They were extremely effective. When the Maoists called a bandha, everything was forced to close: schools, shops, and most offices. No buses, taxis, or cars were allowed on the street, so the only way around was on foot or bicycle. Strikes could go on for days, and came with virtually no warning.

Bandhas were known to turn violent if the prohibition was not respected. Buses and cars were overturned and set ablaze in the middle of the streets during the strikes. A few taxis did still operate, despite the risk. In a country as impoverished as Nepal, the extra money they could make during a bandha was too valuable to pass up. These daredevils covered their license plates with paper so as not to be identified and drove as fast as possible, stopping only to pick up and drop off passengers. Those who were caught were often physically assaulted or had their cars smashed by Maoist sympathizers. Our village, Godawari, was thirty minutes from the Ring Road of Kathmandu; thankfully, we saw very little of that violence.

The frequent bandhas led to shortages of food and kerosene. The food shortages were difficult for us, as prices for vegetables could quickly double during these times. For families barely surviving, though, it was far worse. Finding kerosene was impossible at any price, so our twenty-two-year-old cooking didi, Bagwati, who lived in the house with us and helped care for the children, would cook the morning and evening daal bhat on an open fire in the garden, helped by the children. Cooking rice and lentils for more than twenty people on an open fire takes several hours.

For the children at Little Princes, the biggest effect of the bandhas was that school was closed. School closings were not the euphoric celebrations they were in America, where children pray for crippling snowstorms. Children in Nepal, while they would certainly rather be playing, actually enjoyed school. I attributed that to the fact that going to school was not the inevitable daily event that it was back in the States.

Even when there was no bandha, classes were frequently canceled at the public schools like the one the children attended. The school looked, from the outside, like an abandoned single-floor building, a long mud hut painted white on the outside with a tin roof and a broken slide outside. Teachers were paid almost nothing by the government, and thus had little incentive to even come to school. Chris, the German volunteer, worked in the public school two days a week, and was often asked to stand in for teachers who didn’t show up. If there were no volunteers and the teacher for the five-year-olds’ class was absent, one of the seven-year-olds was sent in to teach.

With frequent school closings, we had a responsibility to keep up the children’s education at the orphanage. This was probably a good thing. I saw one of Anish’s English homework assignments, where he had answered questions about pictures in a book, and the teacher had marked each question correct with a green checkmark, including one picture that showed a man realizing he had forgotten his umbrella at home. Anish’s sentence read: “Man housed umbrella.” I was pretty sure that was wrong.

Chris, Jenny, Sandra, Farid, and I split the children into groups by age, and we each took a room. The children would rotate through our rooms and we would give them a thirty-minute class in a particular subject. Sandra would teach them basic French, Chris and Jenny would help them with reading, and Farid was going to help them not only with their writing skills but with their computer skills as well, using the ancient laptop in the office, one with a huge tracking ball that you rolled around to move the cursor.

I had no idea what to teach them. But everybody else had chosen something and they were looking at me expectantly, and I heard myself blurting out that I would teach them science. Immediately after I said it, I regretted it. Science! My God, if there is something I know less about than science, I wouldn’t be able to name it.

Thankfully, my first group was the youngest boys: Raju and Nuraj. That, at least, was easy. We played Farmyard Snap again. The first card they flipped over was a goat, and I got them to repeat the word. In the village there was real relevance in learning the English word for goat.

“We no learn science, Conor Brother?” asked Raju.

“Goats are science, Raju.”

I saw Nuraj turn to him to ask for a translation, and Raju translated for him that goats were science. Nuraj nodded, and we got back to the game.

Those thirty minutes passed far too quickly, and then a far bigger challenge presented itself. The bigger kids came in. This was trouble—they knew what science was. I once tried to help Bikash, the eldest boy, with his biology homework; he had asked me to explain the male and female parts of a flower.

“Flowers don’t have male and female parts, Brother—that’s just animals,” I informed him.

He looked confused. “Oh . . . but Conor Brother, it says in my textbook that they have . . .” and he opened his textbook to a photo showing the anatomy of a flower, with male and female parts clearly labeled by authors who likely understood a thing or two about the subject.

The boys came in saying “Bonjour, mon frère!” which they had learned from Sandra. Dawa, without preamble, read out loud the story he’d written in Farid’s class.

“There was tiger in jungle and he eat Nishal’s goat. Finish.” He looked up at me expectantly. “You like, Brother?”

“Yes I do, Dawa. Thank you for sharing that,” I said. I waited, hoping somebody else might have something to kill some more time. Nobody had any more stories—apparently they had collaborated on the story about the tiger eating Nishal’s goat.

Unsure what to do, I asked them to sit down in a semicircle. I rearranged them thoughtfully, buying myself time as I thought frantically about something scientific I could tell them about. What did I know? I could tell them that rocket ships went to the Moon, provided they had no follow-up questions. That would take up about sixty seconds.

“Okay, boys, so, you know how—” I began slowly, drawing out my words. Then, miraculously, I was interrupted by Santosh.

“I teach, Brother!” he said, leaping to his feet.

“Yes! You teach, Santosh!” I shouted, my arms shooting skyward in jubilation. “What would you like to teach?”

“I teach water, Brother!”

“Yes! Yes! Water! This is excellent, Santosh! Water is science! You are doing very well! Go!”

I did not care what Santosh did at that point. He could have eaten paper and I would have cried “Behold! Science!” All that mattered was that all eyes were focused on him, not me, and that the clock was ticking.

Santosh was incredibly bright. I had seen him invent toys for the other kids to play using only the bamboo shoots in the garden. When I needed to fix something in the house that was broken, I would ask Santosh how to do it. Even knowing that, I was blown away when he started talking. He taught the group about the water cycle, from start to finish, about the importance of evaporation and what causes dew, and how pollution affects the cycle. I was listening along with everybody else, thinking Really? I had no idea!

The thirty minutes sped by, and I dismissed the class to general applause. The next group came in, the middle kids, the seven- and eight-year-olds.

I waited for Santosh and the others to leave. Then I closed the door and again arranged the children in a semicircle.

“Okay, everybody, today we’re going to learn about the water cycle!”

The children cheered, and I silently thanked Santosh.

THE CHILDREN WERE OFTEN surprisingly independent. Bedtime, however, was not one of those times. In one bedroom, the six youngest boys slept together in one king-sized bed on a thin straw mattress, just like the one I used. Getting each of the six children into bed presented its own challenge. Raju would recount his entire day in painstaking detail, oblivious to your efforts to get him to raise his arms so you could get his T-shirt off. Nuraj would stand completely still, head and eyelids drooping, and allow you to undress him and outfit him in a full teddy-bear suit. After struggling to get his legs and arms into the appropriate holes and triumphantly zipping it up from ankle to neck, his eyes would pop open like an android snapping to life and he’d yell “Toilet!!” and he’d start thrashing around like Houdini in a straitjacket while you picked him up and raced him to the bathroom.

Evenings were a difficult time for Nishal, who was often sulking, if not outright wailing, about some injustice. Volunteers took turns comforting him, but I soon began taking care of Nishal every night. Sulking and wailing at bedtime was one of my defining traits when I was Nishal’s age. I needed constant attention, and I figured the quickest way to achieve it was by sulking. Now I struggled, as my parents must have, to find the right balance between being loving and being strict. It was strangely healing for me; I had never quite gotten over a sense of guilt for my childhood temper tantrums. My mother must have had the patience of . . . well, of a mom, I guess. Making sure Nishal went to bed, absorbing that energy from him, did wonders for both my patience and peace of mind.

One by one we would round up the rest of the children and plop them into bed. When they were all lying down, covered with a large blanket with their little heads lined up in a row like a rack of bowling balls, we would give them all little hugs good night and turn off the lights, then head over to the bigger kids’ room.

There were ten boys in the other room, two kids per double bed. (The two girls, Yangani and Priya, slept downstairs in a room with Bagwati, our live-in cooking didi.) I would come in to find Farid moving from bed to bed, getting one pair to lie down as the pair across the room popped up, a life-sized version of Whac-A-Mole. When the children saw me walk in they would leap up and yell “Conor!!” in the roar I had taught them on the first day, and I would assist Farid with the take-downs. Eventually the pairs of children would huddle together under the blanket for warmth; lights went out at 8:00 p.m. I heard them whisper for a few minutes before sleep took them. The house would fall silent for the first time all day. Then, each night, volunteers would gather in the living room, relax and drink tea, and tell stories about what the kids had done that day.

I recalled times when I had listened to parents speak about their own children, laughing hysterically about seemingly inconsequential things their child had done. I was beginning to understand that sentiment. We took enormous pleasure in recounting something a particular child had done, at how predictable they were and yet how they could continue to surprise us. It made each day completely different, and, at the same time, exactly the same.

I WAS WOKEN UP one night in early December by a loud groaning. It was coming from the boys’ room. I put on my head torch, which I kept near my bed, turned on the powerful beam, and ran into the boys’ room. I scanned the ten beds. I heard the groan again. I moved closer, stopping again to listen for the next sound, like a game of Marco Polo. It was coming from Dawa’s bed. I pulled back the covers to find Dawa drenched in sweat.

“Dawa—what is it? What’s wrong?” I whispered frantically, my face just inches from his.

“Eyes, Brother!” he pleaded, blinking.

“Your eyes? What’s wrong with your eyes?”

“Your light, Conor Brother!”

I was shining my high beam directly into his face. I turned it off and swept him up. He was shaking. I carried him to a spare bed in the volunteers’ room. As I put him down, more groans came from across the room. A moment later I saw Sandra dart into the room, straight for Santosh’s bed. She scooped up the groaning boy, who was clutching at his stomach, and carried him to another spare bed in the volunteers’ room. There was no way to go to a doctor at that time of night, not out here in the village. We sat up with them and soothed them until they finally fell back to sleep a couple of hours later.

The next morning Farid and I took both boys to Patan Hospital in Kathmandu, a forty-five-minute bus ride from Godawari. Inside, we navigated the dense crowd. I kept my head up, looking helplessly at the signs in Sanskrit hoping for a clue as to where to go. I found the admissions desk, and told the woman on duty that we had two boys who needed to see a doctor. She called over a colleague who knew a few words of English, and we struggled to understand each other while an impatient line grew behind us.

The hospital itself was a terrible place. It felt more like an abandoned bus station than a medical facility. Everywhere patients sat or lay down with wounds covered in dirty bandages. We were shuttled between various doctors and made to wait for several hours over the course of the morning. Farid had taken Dawa to another wing to get him checked out, while Santosh and I sat together. Other patients stared openly at us, looking back and forth from me to Santosh, back and forth, until slowly making the connection, and then smiled kindly at me.

We were directed to yet another room, where we were told to take a number and wait our turn. The number on the screen was six. I looked at the number on my piece of paper. Seventy-nine. Ten minutes later, the number on the screen changed to an eight.

After having waited five hours just to get a number, I’d had about all I could take. I sat Santosh down in the recently vacated wooden chair. The doctor glanced up at me and did not ask to see my number. He set to work examining Santosh.

After six hours in the hospital, nobody could find anything wrong with him, and he was released. We found Farid and Dawa waiting outside, holding a small bag of antibiotics for Dawa’s fever, and together we walked back to the bus that would take us the forty-five minutes back to Godawari.

THE MORE TIME I spent with the children, the more I got a sense of how I was going to survive these two months. The key to sanity, I discovered, was understanding that the children did not need to be supervised every second of every day. If Hriteek climbed the small tree in the garden and was hanging by his knees, for example, I told myself that he had probably been doing that before I got there, and that he still had all his teeth and limbs. When we went to the botanical gardens, the lovely enormous park next door, the kids climbed all kinds of trees, fished in the stream, and had sword fights with fallen branches. It was like hanging out with eighteen little Huckleberry Finns.

Even around the house, the children at Little Princes could entertain themselves far more efficiently than I ever could. I made a mistake early on of buying them toy cars during one of my trips to Kathmandu—eighteen little cars, one for each of them. They loved them so much they literally jumped for joy. I felt like a Vanderbilt, presenting gifts to the less fortunate. The longest-surviving car of the eighteen lasted just under twenty-four hours. I found little tires and car doors scattered around the house and garden. Nishal and Hriteek, the pair of six-year-olds, shared the last car between them, sliding the wheel-less chassis back and forth across the concrete front porch a few times before running out to play soccer with a ball they had made out of an old sock stuffed with newspaper.

Though they would never admit it, the kids had far more fun with the toys they made themselves. One boy, usually Santosh, would take a plastic bottle from the trash discarded throughout the village. To this bottle he strapped two short pieces of wood, binding them with some old string. He collected four plastic bottle caps and some rusty nails and pounded them into the wood with a flat rock. And voilà! he had built a toy car. When it wobbled too much going down the hill, he discovered that he could stabilize it by filling the bottle with water. Soon it was racing down shallow hills and crashing into trees. Because he had constructed it, he was also able to fix it. By the end of the day, all the children had built their own cars.

I never bought them anything after that. Instead, I helped them search for old bottles or flip-flops they could use, or saved for them the toothpaste boxes. Those boxes were so popular that we had to set an order in which each child would receive his discarded box. They didn’t really do anything with them except keep them, to have something to call their own. The cars they made, or the bow and arrows they made out of bamboo, or the little Frisbees they made out of old flip-flop plastic—those things were all individual possessions. They happily shared them with others in Little Princes, but at the end of the day the toy or the piece of prized rubbish would go into their individual cardboard containers that were large enough to hold their two sets of clothes and everything else they owned in the world.

A MAN WAS LEAVING the orphanage.

I was a good distance away, walking back to the house after a hike into the hills, but I could see him well enough to know that I didn’t recognize him. That was unusual; we restricted the number of people who could enter the house for the protection of the children. As safe as the village felt, and as protective as the neighbors were of the children, we could not forget the civil war. We were situated on the southern border of the Kathmandu Valley. Just over the hills were villages under Maoist control. When soldiers in single file patrols came through the village searching houses for weapons, our neighbors convinced them to skip Little Princes Children’s Home so as not to disturb the children. To their credit, they always respected this.

Now, a strange man in the house made me nervous. I ran the rest of the way. Inside, I found Sandra and Farid speaking with Hari, the part-time house manager, who had just arrived from his other job over at CERV Nepal. They stopped when I came in, reading my concern. Sandra waved me to sit down with them.

“That man who just left,” she said, nodding out the door. “His name is Golkka.”

“Who is he? I thought we didn’t let strangers visit the children,” I said.

“He’s not a stranger. The children know him,” she said. Farid snorted derisively. Hari said nothing. I waited.

Sandra continued, “The children know him because he is the man who took the children from their villages. He is a child trafficker.”

Then, for the first time, I learned the story of how the children at Little Princes had arrived in the small village of Godawari.

Golkka, like the children, was from Humla, a district in the far northwest corner of Nepal, on the border of Tibet—the most remote part of an already remote country. It is completely mountainous, with no roads leading in or out. Most villages there have no electricity or phone service. There is a single airport; from there, the entire region is accessible only on foot or by helicopter. Many children growing up there have never seen a wheeled vehicle. It was in Humla, impoverished and vulnerable, that the Maoist rebels had created one of their first strongholds.

Golkka found that there was opportunity in such a place: he could have access to cheap child labor. He rounded up children orphaned by the civil conflict, a conflict that had thus far resulted in the deaths of more than ten thousand soldiers, rebels, and civilians. He forced the children to walk many days along narrow trails through the hills and mountains—trails that must have resembled the challenging paths up to Everest Base Camp. They walked until they reached a road, where they could catch a bus to Kathmandu. Once there, he kept them in a dilapidated mud house, offering them up for labor. If they wanted to eat, they were forced to beg on the streets.

When tourists discovered the children, they came to the house and asked what they could do to help. Golkka realized he had something much more lucrative on his hands than a mere work-force. He began bringing in volunteers to visit and care for the children. When they bought mattresses so the children would no longer have to sleep on the cold mud floors, Golkka thanked them, and then promptly sold the mattresses as soon as the volunteers left the country. Clothes brought for the children were similarly worn until volunteers left, then taken from the children and given to the trafficker’s family.

Sandra met these children while volunteering. She vowed to break the cycle of corruption. She raised money from France and offered to take the children off his hands. Golkka sensed another opportunity. He demanded payment, about three hundred dollars per child. This would be a small fortune in a country where the average annual salary was around two hundred and fifty dollars. Sandra refused to pay, but continued working with the government and other nonprofit organizations to secure the children’s release. Eventually, pressure from the Child Welfare Board and other organizations grew too much for him, and he let them go with her. Those eighteen children became the Little Princes.

Three months after the rescue, neighbors reported that Golkka’s crumbling home was filled again. He had gone back to Humla and gotten more orphaned children.

“Why wasn’t he arrested? Didn’t the Child Welfare Board know what he was doing?” I asked.

“They know. But Nepal’s laws are weak. He was the legal guardian of the children—he had found family members to sign custody to him. He could do almost anything he wanted with them,” said Sandra.

“So we can do . . . what, nothing?”

“You have to understand, Conor, this is very serious,” Sandra said, leaning forward. “We had a volunteer here four months ago. She tried to build a case against him with UNICEF and the Child Welfare Board. Golkka found out, and he came to the home and threatened physical violence against her and the children if she continued. She had to leave the country, for her safety and for the children’s safety.”

I didn’t say anything. I was out of my depth. I was only here for another month; this wasn’t my battle. But I found it difficult to control my anger against this man who seemed to be getting away with this, making a profit off the lives of the children. It wasn’t my fight, maybe, but I wanted to join it anyway. I read in Farid’s face a similar sentiment.

“What will happen to the children?” I asked.

“We keep them here, we raise them, and we educate them. They have no family to return to, or at least no family that we know of, except maybe distant relatives who may have signed them away, I suppose,” Sandra said sadly. “Many people—many family members—have been killed in this war.”

“But this guy, we have to let him in when he comes?”

“He’s not just any man,” Hari said, before Sandra could speak. “I know him well. His connections are powerful. He was arrested once, months ago, and he got out of jail after three days because his uncle is a politician. I do not want him here, but we cannot prevent him. He can take the children away from us.” He added, his voice apologetic, “It is Nepal. It is difficult.”

I went to see the children, up in their bedrooms. I was concerned that the visit from a man who had kept them as veritable slaves for two years had traumatized them. Incredibly, they were playing cards and jumping on their beds as if nothing had happened. These were the same kids who cried if they couldn’t find a flip-flop. It was my first glimpse into just how resilient these kids really were. Beneath the showing off, the sulking, the hilarity, there must be an imprint of the terrors they had lived through in Humla—the killings, the child abductions by the rebel army, the starvation. I imagined a steel lockbox at the center of each of them, inside of which they quarantined these memories so that they could live seminormal lives.