Читать книгу Weird Tales 359 - Conrad Williams - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

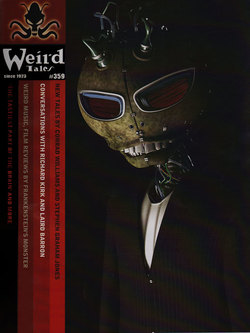

ОглавлениеRICHARD KIRK: WEIRD VISIONS, interview by Ann VanderMeer

Richard A. Kirk’s official bio describes him as “a visual artist, illustrator, and author living in Canada.” But take a closer look and you’ll see so much more. His influences are wide and varied. He takes his cue not only from other visual artists but from all creative endeavors as well as the natural world around him. Kirk’s attention to detail allows the viewer to see wondrous things in the most ordinary of objects as well as the beauty in the weird. And it is important to take a closer look, because that is when his work truly comes to life.

WT: Have you always known you would be an artist? What is your earliest memory of creating art and what did you create?

RAK: I have one piece of early artwork, a crayon drawing called “Fish” that I did in public school. Unfortunately I have no memory of making it. My earliest memory of drawing is sitting in the kitchen, in the very early morning before anyone else was up and around. I used to make a pot of tea and draw monsters on pads of cheap Manila paper. My obsessions as a kid were insects and Daleks, no doubt much to the general misery of the insect population. I can’t speak for the Daleks.

After reading Gerald Durrell I decided I basically wanted to be Gerald Durrell, and spent hours drawing imaginary zoo plans. Drawing was always a way for me to create worlds. For the longest time I clung to the idea that my future would have something to do with insects but art won the day.

When I was young, English comics were my introduction to art. Later, I discovered many of the classic illustrators such as Aubrey Beardsley and Ernest Shepard. I think my work now has such a strong connection to my love of books because of those early illustrations. It was book illustration above all else that made me want to start drawing in the first place. That is why I see such a tragedy in the current trend in cutting back on school libraries.

WT: Would you describe your workspace?

RAK: My studio has moved around the house, but for the past few years it has occupied what normal people would describe as a dining room. It contains one of my drawing tables, an old library card catalogue and atlas stand that I use to store supplies, a paper rack, way too many books for the space, and a cabinet full of found bones, skulls, fossils, and other oddities. There is also a small dog that, given half a chance, loves to sleep on my drawing table. The studio has two windows facing south and east so the light is good. It is a good place to be and central to the rest of the house, which means I can be an artist and still see my family.

WT: You work in a variety in mediums, one of them being silverpoint. Can you tell us a something about this process and why you work in it?

RAK: I discovered silverpoint when reading Patrick Woodroffe’s book A Closer Look. It seemed ideally suited to my style so I immediately investigated the technique. Essentially, it consists of drawing on a prepared ground (with a slightly toothy finish), using silver wire. I load a piece of wire into a 0.5 mechanical pencil to use as a stylus. Silverpoint offers unparalleled beauty of line and detail. As the drawing ages, the silver particles tarnish and give the image a nice brownish hue that is often described as “smoky.” I could happily work in nothing but silverpoint. I never tire of it.

WT: How do you decide what method/ medium to use for each project?

RAK: How the piece will be used usually dictates the medium. If the drawing is slated for use as a book illustration, I use ink as a medium because it reproduces well, whereas silverpoint is difficult to reproduce. When I am working on a personal piece, or a piece for a show, I let the subject guide me. I love the tension of making grotesquely beautiful images with a refined medium like silverpoint, but watercolor and oil are fun too. Some subjects require a more delicate touch than others.

WT: What is the most unconventional material you have used in your work?

RAK: I tried to incorporate wasp paper and mouse bones into a drawing once, with mixed results. I like to make assemblages out of found materials. This is where I am most likely to use unconventional materials. I like bones, paper, wire, certain kinds of weathered plastic, all manner of detritus that you find on the parts of the beach most people would rather not go. That aspect of my work, which I don’t get to indulge in nearly enough (though I am slowly piecing together a workshop with assemblage in the back of my mind), is influenced by the work of Rosamond Purcell and Jan Svankmajer in its concern for decay, or the effect of time on objects. When I get old and unable to draw, I fully intend to start filling rooms with crazy Quay Brothers-like sculptures!

WT: Does music influence your work?

RAK: I am a big music fan and always listen to it in the studio. It helps me go to the “other” place where my mind needs to be in order to work. The rhythm helps me keep motivated. I listen to a lot of different kinds of music, but when I am really focused on a drawing, I like strange abstract electronic music that takes unpredictable turns. Lately I have been listening to Seefeel, Black Dog, Vex’d, Blackfilm, Autechre, Hecq, and, of course, The Residents. On the other hand, I like Kathleen Edwards, Fleet Foxes, and Muse. The main thing with any creative environment for me is to establish a space, however fleeting, where the “otherness” that resides in my drawings can exist with minimal interruption. I’ve never been someone who is inclined to whip out a sketchbook on a bus and start drawing. Music helps creates a nice creative bubble.

WT: In addition to being a visual artist, you are also a writer. How do these two different forms of artistic expression influence each other in your work? Which comes first when illustrating your own work?

RAK: Umberto Eco writes that he begins each novel with a seminal image. That idea resonated with me because it is also how I approach my writing. For example, with my novella, The Lost Machine, I had the image of a man standing before a large block-like prison in the middle of nowhere. His head was wrapped in cloth and he had stones floating around him. Obviously the image is just a starting point, but it was enough to unpack the whole story. The process is very similar for both image making and art. I begin with an image, and then begin building that image out from the center. My drawing “The Seed,” is about this process. Imagine that the seminal idea is something super dense that keeps pushing more and more information out. When I can feel that creative surge, I know I am on to something. When I am writing, I am always thinking in terms of images. It is very cinematic in a sense. I do have to keep a leash on things or I can spend three pages describing the rust on a padlock. In terms of process, when illustrating my own writing, I do the writing first, and then the finished illustrations. Until that point most of the images are in my mind though and there is constant interaction.

WT: A lot of your work is influenced by nature. What is it about the natural world that intrigues you?

RAK: There are certain places where I can feel myself relax, bookstores and libraries fall into this category, and so do gardens. It is just a place I love to be because thoughts and ideas seem to come easily there. The forms of plants and creatures are endlessly inspiring. We’ve never used insecticides or herbicides so the insect life in our garden is very rich and the plants tend to get a little overgrown. Of course the garden conjures up a sense of childhood and magic. All these things are very good for an artist with my interests. Although I know to a certain extent it is an illusion—a garden is a human invention—the magic of it is that it feels like it is outside of human concerns. It is a respite from the relentlessly mediated systems and structures outside of the garden. I would love to write a book on the garden in literature and art. There are so many great ones, from Mary Norton’s The Borrowers series to “Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

WT: What was one of the most frustrating projects you worked on and why? What was the most exciting project?

RAK: Well I have to say the most frustrating project was a book cover for a publisher who shall remain nameless. I did a beautiful monochromatic oil painting, which was approved at every stage and then rejected for no good reason on delivery. I was mostly disappointed because I knew in my heart that it was a cool piece. In the end I sold it for a very satisfactory sum to a woman who had never even read the book. My most exciting project to date, wow, that is a really tough one. I think I would have to say the album cover work I did for Korn. Of course it was great to work with the band, but really it is just about having a great memory of being at home in my studio in the summer, with the windows open, my dog in the studio and my wife and daughter doing their own creative things nearby. I was feeling really energized. It is great when that happens.

WT: Although most of your work is quite dark, it’s also very beautiful. How do you find beauty in the grotesque?

RAK: That is a very interesting question and goes to the heart of what we consider beautiful or grotesque. Is something inherently grotesque/ beautiful, or is it something that we construct? I think the latter. When I’m working on an image I try to find and reveal the heart of what I am depicting so that the viewer can feel a connection. Sometimes that relationship is based on humor or absurdity, other times through contemplation, or a mood such as sadness and melancholy. I want the viewer to feel something of themselves in the subject. By disrupting the ordinary I try to guide the viewer into an unexpected relationship with the image.

Notions of the grotesque are rooted in a fear of disorder, things not as they should be. Beauty lives there too; all true beauty has a flaw. My favorite quotation is “there is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion” by Frances Bacon. My artistic production is centered on finding that liminal space between the two, where you can feel the beautiful and grotesque as a simultaneous thing.

In terms of technique, I like to render subjects in a way that privileges composition, balance, beautiful line and unhurried execution. I never create original art on the computer. That is not to denigrate the efforts of other artists that do, I simply feel that you use another deeper part of your brain when you are making the marks with your hands. I think most viewers will take the time to look and spend time with your image, if they see that you are engaging them aesthetically and honestly.

WT: What’s next for you? What are you looking forward to?

RAK: In the short term I’m working on a number of book projects. I’m doing thirty illustrations for the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Clive Barker’s Weaveworld, and an early Barker novella called Candle in the Cloud. I’m also doing a book project with Jeff VanderMeer where I will produce illustrations inspired by his Ambergris universe and then he will write short fiction riffing off the art.

In addition, I am writing and illustrating a novel called Necessary Monsters, which is a follow-up to an earlier work The Lost Machine. I want to do a lot more writing. It is an area that I am creatively drawn to and the process of designing and creating books is very interesting. My wife and I started Radiolaria Studios in 2010, which will produce interesting small run books based on my art (we did The Lost Machine in 2010). And eventually I would like to secure a literary agent and sell a novel to a commercial house in order to engage a broader readership.

One the visual art side of things, I am going to be creating some larger works for a gallery show, and produce an art book. I am looking forward to being the artist guest of honor at the 2012 World Fantasy Convention in Toronto. It seems like something new is always popping up, and so I have to say I am looking forward to the unknown!