Читать книгу Rites - Cora Bissett - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCO-CREATORS’ NOTES

Rites began as an idea in 2013 when I was chatting with a friend from the Scottish Refugee Council. As a Children’s Officer there, she was at the forefront of issues which were arising in Scotland. She pressed upon me an urgency to create a new piece which somehow shed light on the practice of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

She had seen various young girls presenting at the Scottish Refugee Council who had suffered extreme forms of FGM. These girls were now in Scotland and they deserved to be supported as any other child would.

But it also raised the question; “HOW do we help?” If these girls are coming from communities which deem FGM not as a ‘wrong’, but as a deeply and dearly held ritual, how does a society wade in and stop that without doing more damage?

I thought a lot about how I should tackle the subject, and the more I read, the more I realised that you cannot talk about FGM without talking about race, cultural understanding, gender politics and the whole continuum of gender violence across the world. I strongly felt that I needed to work with someone from a cultural background which was closer to the subject than my own.

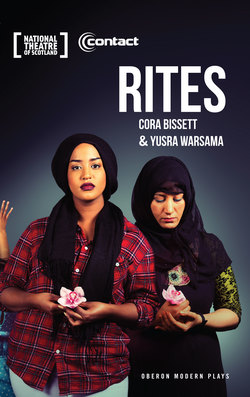

Fortuitously, I met Yusra Warsama when she was performing her beautiful poetry at the Edinburgh Fringe and we connected. I tracked her down and asked if she would like to co-create this piece with me.

That began a long and complex journey which has seen us interview people up and down the UK: FGM survivors, doctors, midwives, lawyers, MSPs, social workers, activists, campaigners. It has taken us from Edinburgh to Manchester, Glasgow to Bristol, Birmingham to Cardiff and places in between. We have tried to reflect myriad voices and experiences. We have tried to convey for an audience why it happens, and how difficult it can be to change. We want to give voice to those people who feel stigmatised by the current intensity and focus of the anti-FGM campaign; we have tried to give balance where tabloids scream horror. We have tried to extend compassion and understanding where media screams demonisation.

I hope Rites provokes thought and debate. There are no easy answers, but by putting a taboo subject out in the public domain, and trying to shed light on the people who practise and the reasons they do, I hope we can offer something useful to the current discourse on the best way forward.

Cora Bissett, Director and Co-Creator

The awareness of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting is very present for us all at the moment with increased media attention through the work of great campaigns, invariably connecting us to the world and to a massive human rights issue.

Being a Somali woman, and someone who works in the theatre industry I have been invited to explore the issue several times over the years, but I wasn’t sure if the complexities surrounding FGM/Cutting could be communicated.

There was also a question for me as a theatre-maker about never having seen people from cultures that practise FGM being presented in theatre before. So…where do you start?

How do you present, for example, African women on the British stage through a truthful lens, beyond the stereotypes and archetypes that we know? When I hear about FGM/Cutting is it our narrative projected on to these women? Or is it their own narrative told to us?

By chance I met Cora Bissett at the Edinburgh Festival 2013. Here was a talented woman passionate about telling people’s stories on stage, and I thought this may be the time so to speak. The world’s gaze is on FGM.

After an attempt to give voice through storytelling to those directly affected and those working on the issue, it became apparent that verbatim was the best way to tell this story, the most honest way to articulate the complexities and detail, the way to do justice to very real life experiences.

This set us on a journey of research and interviews and how detailed the truth became once we begun…

In my ‘community’, FGM/Cutting has thrown up a lot of issues along the way. I think about some of the women I see around me; they are wonderful beings that are moving forward despite this thing that has been inflicted on them.

So for me approaching this subject for a theatre piece raised even deeper questions. Who are these women who live with this and amazingly get on with their day to day lives, and the ones who can’t? How do you show the honest textures of these people?

Using verbatim text has allowed us to do something that is based in truth from actual people that no writer could invent, giving us the opportunity to see the nuances of truth. I could go on about the power of the edit and how this works in collaboration, how a single “cut and paste or delete” can reduce someone’s thinking or enhance them like angels…..

But to put it briefly, it has been difficult taking from women’s experiences and it has been joyous hearing powerful women and it has been affirming hearing the people who have taken the issue up in their work as humanitarians.

I hope that what you experience narratively is reflected in the two quotes below;

I think I am safe in saying that none of us who has studied the practice in its context are so theoretically myopic or inhumane as to advocate its continuance…understanding the practice is not the same as condoning it. It is, I believe, as crucial to effecting the operation’s eventual demise that we understand the contexts in which it occurs as much as its medical sequelae.

Janice Boddy, Body Politics 1991

Truth and beauty.

Amiri Baraka, 1934–2014

Yusra Warsama, Co-Creator