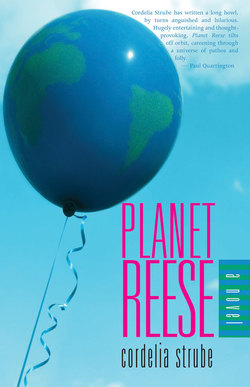

Читать книгу Planet Reese - Cordelia Strube - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

8

ОглавлениеSerge Hollyduke asks to speak with Reese privately regarding Marge Stallworthy, the kindly senior citizen whose walker bumps the chairs of the other callers. “She stinks of shit,” Serge explains, “nobody wants to sit beside her.”

“Since when?”

“It’s been getting worse, it’s because she spends too long on the phone.”

“She gets pledges.”

“She slows things down. Anyway, nobody’ll sit beside her. They’re threatening to quit.”

Reese surveys the pool of callers. Aside from the truly desperate who barely speak English, he sees mostly adolescents without humility or tact, who will undoubtedly spill Coke on their consoles and short the computer. He despairs when he considers that it is entirely possible that he will spend the rest of his life managing adolescents. The ones in Marge Stallworthy’s vicinity have angled their chairs away from her. Some of them pinch their noses.

Serge runs his hands over the short hairs on his head. “I’ve got ten callers on the Crohn’s and Colitis program. They’re supposed to spend ten seconds per call, Marge is at like six hundred.”

“She’s doing two hundred percent better than the ones zipping through,” Reese says. “It balances out.”

“I’m talking mutiny here. Nobody wants to sit beside her.”

If possible, Reese would like to shield Marge from youthful cruelty and scorn. He watches the live display that tracks the callers’ performances. She continues to out-perform the boy in dreads and the halter-topped girl who regularly presses disconnect when the dialler beeps because she’s in deep discussion with her halter-topped neighbour. Surprisingly the team, overall, is not doing badly. Crohn’s and Colitis are not easy sells. Marge may have an edge because she’s incontinent herself and can genuinely plead the cause. “I’ll talk to her,” Reese says. In the meantime he sits down with his technician to look at donor history and establish exclusions for the Voice of First Nations campaign. “I’d stay away from the Conservative party,” he says. The technician, Wayson Hum, nods as though Reese has given the correct answer. Wayson Hum rarely speaks or makes eye contact with anything but monitors. His father is a grocer in Chinatown. Wayson frequently nibbles on fruits and vegetables Reese doesn’t recognize.

“What about geography?” he asks. “Have you set up the time zones?”

Wayson nods as though Reese has given the correct answer.

“Let’s suppress all donors who haven’t given for two years,” Reese suggests. “And suppress all donors who gave over fifty dollars, we’ll do them when the team’s up to speed.”

He spies Marge leaving the washroom and heads her off. “Marge,” he asks, “do you have a minute?”

“Certainly. Queer weather we’re having. I had to turn up my thermostat to get the damp out of my bones.”

He opens the door to the boardroom for her, noticing that she does stink of shit, and waits as she hobbles over to the table. He pulls a chair out for her. “You know how the dialler works, don’t you, Marge?”

“The what?”

“The computer that makes the calls.”

“Oh yes, very clever.”

“The thing is, if one person is spending a long time on the phone it confuses the machine. It reduces the average.” Marge blinks, clearly having no idea what he’s talking about. “The machine works on averages to time calls,” Reese clarifies. “If the average is reduced, the dialler assumes callers won’t be ready, which means people are sitting around with nothing to do.”

“The young people.”

“That’s right.”

“I do so enjoy them. They’re quite lively, aren’t they?”

He tries to imagine her young, without humility or tact, in a halter top. She has seen twice as much life as he has and she is still going, still smiling, still talking about the weather. Twice as much life as he has had would kill him. “I was wondering if you’d like to sit by the window,” he says. “It’s a corner seat, you’d have more privacy.”

“Oh that’s quite alright, I like being with the young people.”

“I understand, but the thing is, we’re starting a new campaign and I don’t want to mix up bowel disease with Indians, and you’re doing so well with bowel disease.”

“Yes, well, I do my best.”

“I know you do.” He can see that she’s disappointed, that she doesn’t understand why she is being ostracized. “Let’s get you set up. I think you’ll like it, you’ll be able to see daylight.”

On the floor, a new caller who works nights at a bakery is distributing day-old Danish, unaware that food on the floor is prohibited. “They’re a bit sawdusty,” he admits, “but what do you want for free.” The adolescents grab at the pastries as though they haven’t eaten for weeks. Reese sees Serge Hollyduke fast approaching, his jaw clenched, to enforce discipline. The caller offers a lemon Danish to Avril Leblanc. “Hi, I’m Holden, would you like one?”

“I don’t do wheat,” she says. “But it’s sweet of you to offer.”

Holden then offers the lemon Danish to Serge. “Do you do wheat, sir?”

“Food is prohibited on the floor,” Serge says.

“Really?”

Serge scowls and turns to Reese. “There’s an urgent call for you.”

Immediately Reese imagines his children mangled in a car crash. He is in his office within seconds. His mother is on the line. “It’s your father,” she says, “he’s fallen off the toilet again.” Within half an hour, Reese is dragging his father on the hall rug to the stair glider.

Betsy hovers. “Every ten minutes he’s straining. Getting himself off that chair and onto the toilet. He’s taking laxatives, stool softeners ...”

“How would you know what I’m taking?” Bernie demands.

“Tell him you can’t pee anymore, Bernard, tell him what’s going on, he’s your son, he should know.”

“What’s going on, Dad?”

“She’s driving me nuts, that’s what.”

“You do look paler, Dad, and you seem weaker.”

“Why won’t anybody leave me alone, would you tell me that?”

“Because you keep falling off the toilet, Bernard.”

Reese can’t lift his father onto the wheelchair. Two days ago his father could assist him. “You’re losing strength, Dad. Are you eating?”

“You try eating when there’s nothing coming out the other end.”

“He had Campbell’s soup made with cream. I told him to have plain broth but oh no ...”

“I can’t lift you by myself,” Reese says. “You’re going to have to make some effort here.”

His father lets out a small muffied cry of either pain or despair before collapsing onto the stair glider.

“I think we should call an ambulance and get you to the hospital,” Reese says.

“Out of the question.”

“Do you want to die?” Reese says harshly because he can’t do this anymore. “That’s what’s going to happen, you’re going to die.”

“You don’t have to shout,” Betsy says.

“How long ago did they tell him he should be on dialysis? Weeks ago. He’s losing strength, he can’t shit or piss, what do you think’s going to happen?”

“He’s right, Bernie. It’s not right. It could be serious.”

His father sits with eyes closed, shrunken.

“I’m calling Med-Merge,” Reese says.

A wild-eyebrowed Greek puts his finger up Bernie’s rectum and tells him that his bowel must be disimpacted. The doctor leaves to search for a nurse who would be willing to do the disimpacting. Reese waits for his father to sit up. When he doesn’t, he puts his hand on his shoulder. “You alright, Dad?”

“They send me a Greek.”

“He seemed alright.”

“He’s incompetent.”

“How do you know?”

“He doesn’t know what he’s doing.”

“What should he be doing?”

“Not what he did.”

“Did they do it differently in 1948 when you were in medical school?”

“Don’t act smart.”

A fierce Jamaican nurse appears, ordering them into the corridor.

“Shouldn’t we be in the room for the disimpacting?” asks Reese.

“I’m not responsible for any disimpacting. Dr. Panaglotopoulos should have done it when he did the rectal.”

“So what do we do now?” Reese inquires.

“That’s up to Dr. Panaglotopoulos.”

“Where is he?”

“As you can see we’re very busy.” And she’s gone, lost among the patients stranded on wheelchairs and gurneys, waiting for care, beds, death.

“Are you hungry, Dad? I’ve got a Crispy Crunch.”

“Save it for your mother. Maybe if she eats enough of them she’ll have a cardiac arrest. Where’s the can?”