Читать книгу Terry Pratchett - Craig Cabell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Serious Note on the Text

Оглавление(and a bit of a rant)

Once upon a time Terry Pratchett’s agent Colin Smythe walked into a well-known bookshop and asked where he could find the latest title by his author. Despite the book spending four weeks at number one in the bestseller lists, it couldn’t be found in that part of the bookshop. Smythe was informed that it could be found in the science fiction/fantasy section, giving the distinct impression that books in that department were not worthy of the bestseller bookshelves, even though the title in question had outsold all other bestsellers for several weeks.

For me, it’s not only the injustice that this narrow-mindedness conjures up, it is the superficial labelling of two genres under one heading. Although science fiction and fantasy do come under the umbrella of speculative fiction, they follow two different historical patterns. Fundamentally, science fiction has to be based upon a natural projection of current science, while fantasy doesn’t need any of that but has a strong tradition of dwarves, warriors, wizards and dragons. The greatest visionaries in both genres are a million miles away from each other, people such as HG Wells and JRR Tolkien, or Isaac Asimov and CS Lewis. People did believe once upon a time that there was life on Mars and so was born The War of the Worlds, but Wells’ masterpiece says much more about the vulnerability and scientific naivety of mankind than just speculating about creatures from another planet, and that’s what makes the book so valid today. Conversely, there is no Narnia at the back of the wardrobe, with fauns, talking lions and ice queens (well, not when I last checked), so The Chronicles of Narnia sit squarely in the fantasy genre.

One could argue that The Lord of the Rings created a history that has many parallels with our own great wars and great warriors, and involves the birth of a true language and the spirit of legend – stories passed down by word of mouth. But Hobbits are not based upon a scientific certainty, nor elves or walking/talking trees. The Lord of the Rings is a fantasy. I applaud its ‘fellowship’ and concede that the loyalty and honour Tolkien’s great novel demonstrates is at the heart of every strong friendship in the real world, but dragons don’t exist. On the other hand, Asimov’s Foundation series was based upon political tensions in a science fiction setting. It is as cerebral as Wells’ The Shape of Things to Come, but, unlike Wells’ novel, impossible to film. Asimov, like Robert Heinlein, took politics into outer space and found an even more tangled web of intrigue and malice. One can argue that Pratchett weaves politics into his fantasy novels in much the same way, but the fundamental difference is that in science fiction it could conceivably happen because it is a forward projection, whereas in fantasy it can’t, so it can only be satirical at best.

There is a discernible difference between science fiction and fantasy and that mindset is echoed throughout this book. Yes, parallels can be drawn between the two genres, but they don’t necessarily have the same audience. TV’s Doctor Who is not a fantasy series; it is a science fiction adventure series and has always been so. Conversely, a novel such as The Neverending Story cannot be classed as science fiction because it is an impossibility, something that can’t come true in the real world, so it is fantasy.

Sometimes the speculation of the writer can be thought ‘fantastic’ even in the science fiction genre, but this is normally associated with the long-term vision of the writer. Again, HG Wells offers us a classic example with The Island of Doctor Moreau, where he predicts genetic engineering decades before it was ever dreamed of. Then there is Jules Verne and his breathtaking 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; the underwater ship – the nuclear submarine – dreamed up with accuracy.

It is important to understand that there are two genres within the forum known as ‘anorak’. There are also two different audiences that cross over as much as those for detective fiction and historical fiction. ‘And what of the horror genre?’ I hear you cry. Yes, that sits next door to the double-header label of science fiction/fantasy in the high street, as it is also part of anorak heaven; but, oddly, horror fiction can sit on the bestseller shelves, so it is not as poor a relation as science fiction or fantasy in that respect. Not true? Consider this: a writer such as Clive Barker will write either a fantasy novel or a horror novel – never really a science fiction novel – and sit on the bestseller lists because he is known as a horror writer; just as Stephen King sat on the bestseller list with The Eyes of the Dragon and his Dark Tower fantasy series (and that’s ignoring the fact that certain horror novels are now labelled ‘chiller’).

Some people will argue that science fiction and horror are the same genre, or complementary genres. Indeed, I have had many an unresolved discussion about that in my days at Book and Magazine Collector. Does Alien sit alongside Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Strangely, yes – because both are science fiction. If the aliens murdering innocent people and breeding in a horribly grotesque way upset your delicate stomach, making you cry ‘horror’, then that is in itself ignoring the horrors of mother nature, such as the female black widow spider killing and eating her husband after mating. (Does the creature in Alien not behave, in some ways, like a black widow?) So science fiction is a fiction based upon science, and where’s the horror in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy? There are always crossovers, people pushing the boundaries, but essentially horror is horror, science fiction is science fiction and fantasy is fantasy. They all have their traditions, specific traits and audiences and one should accept that, or at least popular high-street bookshops should when stocking their bestseller shelves.

Going back to Pratchett not being on the bestseller bookshelves, let us observe that he is now. Like Stephen King, James Herbert et al, he is a fundamental part of the ‘establishment’ of authors who are now bankable products for the high street, but some genre writers are still being ignored. Why? A general feeling is that the problem is endemic in the UK. If a book is science fiction or fantasy it isn’t taken as seriously as ‘grown-up’ genres such as crime and historical fiction. In the US that isn’t the case, as science fiction and fantasy have a huge following and are taken very seriously. Also, the horror genre is turning slightly and becoming more true to life, which gives it more credibility and has sparked its offshoot of chiller fiction.

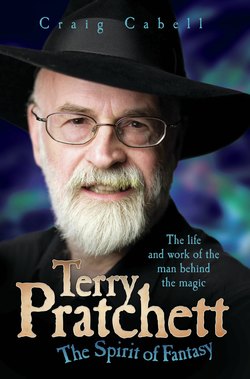

This book is about the fantasy genre and one of its greatest practitioners, Terry Pratchett, a man who has earned his place on the bestseller lists and is still continuing to break down the boundaries of his chosen genre.

‘Science fiction is a subset of fantasy.’

Terry Pratchett

The above quote cannot be overlooked. I deliberately mentioned a science fiction show called Doctor Who earlier. Pratchett has written about this show in the past, and, although he claims that he watched the very first episode back in 1963 and enjoys watching the show today, he is quite appalled by how the Doctor can expound some fast-talking reason to explain how he has just saved the universe yet again. Pratchett goes on to explain that the logic behind some of the Doctor’s solutions is just too ‘fantastic’ to be science fiction, so the stories are therefore fantasy. To my mind, this is where the genres get muddied. Doctor Who is set in outer space and is a children’s science fiction adventure series (so more pace and less explanation are accepted). It is about an alien with two hearts, not in itself a leap of faith. His ship is bigger on the inside than the outside, an interesting scientific hypothesis, and he has the ability to change his appearance – to regenerate – when his body gets tired or damaged. OK, most of that is science fiction, but ‘What about the regeneration?’ I hear you cry. Let us consider a quote from one of the greatest writers of the macabre, Algernon Blackwood:

‘The body, they assure us, changes its atoms every seven years or so, being therefore totally different at twenty-eight from what it was at twenty-one, but science does not commit itself with regard to mental changes, such changes being doubtless incommensurable… am I the man who wrote these tales so many years ago, or am I someone else?’

Algernon Blackwood (Author’s Preface, Selected Tales)

I do agree that the sonic screwdriver is overused nowadays, but the main problem I have with Doctor Who is that it is disposable. Each episode is a rush against time that has to be killed dead in just under 50 minutes (or maybe two 50-minute episodes if you’re lucky). The attention span of the television consumer has dwindled over the past 50 years. In the 1960s, Doctor Who could easily stretch a story over six or seven weeks (at least) in episodes of 25 minutes, but the present fan is apparently unable to cope with such frustrations. Life in the 21st century moves at a much faster pace; everybody wants their entertainment now. Music and movie downloads have made the younger consumer less patient: they don’t need a lyric booklet with pretty pictures with their favourite CD, they just want the music on their iPod now; they don’t want a hardback novel that has to be stored and loved, they want titles on their Kindle now. Things need to be done immediately, and society as a whole has begun to accept this.

As we move into a more computerised/virtual world, we find that taste is dictated by TV and word of mouth (that’s if you can get the headphones off your friend in order to speak to them). People have become more insular, younger folk pinned to their bedroom laptops to prod a friend on Facebook, under-age youths assassinating criminals and Nazi zombies on PS3 then gloating about it on Skype, or texting their poor little fingers to oblivion (surely bad for teenage girls’ fingernails?).

Traditional values are being reassessed. The LP lost out to the CD and now the CD has lost out to the download. Video lost out to the DVD, but the DVD has now lost out to the download too and, eventually, the time-honoured book will lose out to the download as well. But more obscure traditions are going too (evolving?). The photo album is no longer a tangible part of a family bookcase; it sits in a virtual library or on a computer backup system. The wristwatch is now a digital display on everybody’s mobile phone rather than a possession that sits on an individual’s wrist. The downside to this latter change is that it’s just a matter of time before children will not be able to tell the time on a traditional clock face.

Is what I’m saying science fiction? Indeed, some of it is. It is a forward-looking projection of the near future, but it is not a fantasy of the near future. That would be something like every house having a red dragon that told the time, televisuals plumbed straight into the consumer’s head by organic scart lead and controlled by blue pixies listening to Led Zeppelin, and a flat Discworld sitting on the back of four elephants standing on the back of a great turtle swimming through space.

My analysis of different genres in this book is based upon the beliefs set out above. I apologise to high-street bookstores for any inconvenience caused, but there are defining lines within genres, and Pratchett knows that too. But, I hear you cry yet again: the turtle in the Discworld is travelling through space, so surely Discworld is science fiction or at least a strong crossover?

I totally disagree, because the fantasy outweighs the science fiction. There is no deep exploration of space across the Discworld novels. There are wizards (even a female one), witches, dragons, dwarves, goblins, and much more fantasy imagery than there are science fiction elements. To understand Discworld and the life and work of Terry Pratchett, you have to go to what is at the heart of his passion for writing and at the heart of his most important series – fantasy – otherwise nothing fantastic can come from any analysis of his life and works. And if the high-street bookshops refuse to place fantasy novels on the bestseller shelves, then they are clearly overlooking one of the most popular genres and not addressing the public’s need for some extreme escapism in these troubled times. No wonder so many people now shop online. The ability to browse in bookshops will become a thing of the past, bookshops will cease to exist, and consequently people will become more insular – and less broad-minded – about their tastes. The eclectic consumer will become a thing of the past, so perhaps the fantasy novel will become an important genre, one that teaches people to use their imaginations again, to step back from the machines they so slavishly play with.

I recall the journal of the publishing industry, The Bookseller, calling for something to get children off computer games and, just when all seemed lost, up popped JK Rowling and the young Harry Potter. At that time, Pratchett was the country’s most popular writer, but now we can say the top two writers in the country are both fantasy writers. And if that is not an interesting fact for you, witness the fact that Harry Potter books cannot be found in the science fiction/fantasy part of the bookshop, nor the children’s section, nor even the general fiction department: they sit on the bestseller shelves.

It is important to have genres, to define what we as consumers want for our entertainment, and let us hope that the high street wakes up to the importance and popularity of the fantasy genre and gives it the respect it so richly deserves. Yes, people do have their own interpretation of what fantasy is, and that may muddy the waters somewhat, but if great works of fantasy are to be showcased, then there must be an area of the bookstore that is forever fantastic and that includes not just the latest sword-and sorcery-titles but many of the books I list in the Further Reading section at the back of this book. There is more to the fantasy genre than meets the eye. Women didn’t always wear tight black leather and ringlets; certainly not Alice in her wonderland, not Hermione Granger, and certainly not the women and children in Hamelin town by famous Hanover city!

‘He started and rubbed his eyes. He had been so absorbed in the latter-day substitute for a novel, that he awoke to the little green and white room with more than a touch of the surprise of his first awakening.’

HG Wells (When the Sleeper Wakes)