Читать книгу Radical Theatrics - Craig J. Peariso - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

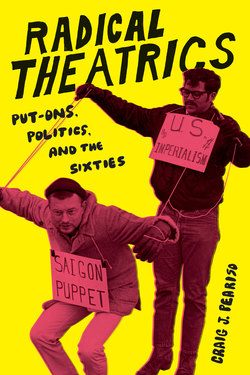

Оглавление1. MONKEY THEATER

IN A 1970 COMIC STRIP TITLED “ABBIE HOFFMAN’S CHARM SCHOOL,” Paul Laikin and Jerry Grandenetti lampooned Hoffman, the Yippie “leader” and media darling, for appearing to revel in his ironic celebrity status. The strip depicts Hoffman guiding students through a course in the etiquette of activism in an age of media saturation, telling them, for example, that when protesting, what one yells at the “pigs” is of great importance: “No more four-letter words. Remember, you’re on TV and they’ll bloop you out. We must use different kinds of obscenities suited to the medium. Obscenities that will really shock the TV viewer. Like, for example, instead of yelling ‘You filthy pig!’ at a State Trooper, we yell ‘You have bad breath!’”1 Later, Hoffman tells the class that throwing rocks at the police

is also out this year. They don’t dig that jazz anymore. The same goes for beer bottles, Molotov cocktails and Clorox jars. Makes ’em get mad and they start retaliating. What we gotta throw is something like, deadly. Are you ready for this? Garbage! Man, like, garbage is really groovy. . . . One important thing about garbage—since TV is covering all this, we can’t just throw any kind of garbage. We gotta throw colorful garbage. Like ferinstance, tangerine peels are wild because they’re a bright orange. Leftover meat bones are also groovy, if they are a nice brown. Likewise, with grapefruit skins you get a crazy yellow. Only lay off egg shells as they’re too white, and coffee grinds which are too black. Remember, we play to color TV!2

Finally, with the police moving in to adjourn the class and administer beatings, Hoffman feels compelled to tell his students what to do “when the pigs start closing in on you.” Faced with the threat of real violence, however, he loses his studied cool, breaking off midplatitude to shout, “RUN LIKE HELL BABY. . . . When they start closing in, it’s every man for himself!”3 And, almost predictably, as the police carry Hoffman away he reminds his students that they should “call my agent at the William Morris Agency” for the time and place of their next meeting. While not as nuanced as some of the arguments concerning Hoffman’s political work, Laikin’s and Grandenetti’s cartoon nonetheless spoke to the anger that a number of activists felt toward “movement celebrities.” Seemingly co-opted by their own stardom, these “leaders” appeared incapable not just of speaking for their own constituents but of speaking meaningfully of opposition at all.

But what if the point of Hoffman’s activism—or media mythmaking, as he called it, indicating the extent to which his approach to political action was inseparable from the creation of falsehoods and tall tales—was not so much to use the media as a means of broadcasting “real” revolutionary views or “correct” revolutionary ideology as to turn the apparent futility of opposition into its own form of historically and technologically mediated resistance? To answer this question, I would like to look closely in this chapter at Hoffman’s political actions, and at the arguments of a number of his critics. I will look, specifically, at the work of Emmett Grogan, founder of the San Francisco–based guerrilla theater group known as the Diggers, and Theodor Roszak, the author who in 1968 coined the term “counter culture,” defining it explicitly in opposition to “extroverted poseurs” like Hoffman. Finally, I will turn to the criticisms of activist and independent filmmaker Norman Fruchter, who in 1971 argued that Hoffman had only betrayed the youth culture for which he claimed to speak. For each of these commentators, Hoffman’s version of political activism was ultimately counterproductive because of its relation to the mass media. Quite interestingly, however, the arguments of Roszak and Fruchter, like those of Robert Brustein, were each based primarily in a reading of the works of one of Hoffman’s mentors, Herbert Marcuse. Drawing on Marcuse’s works of the 1950s and ’60s, these authors dismissed Hoffman for his apparent faith in the media’s ability to aid in bringing about revolutionary social change. Hoffman’s willingness to engage the media, they argued, merely indicated the extent to which he had mistaken images and performances for reality. By looking at the ways in which Hoffman courted the media, however, one might argue, to the contrary, that his antics took Marcuse’s work more seriously than any of these authors recognized, and that, in turn, his media mythmaking may have been most radical precisely when it seemed to these authors most compromised.

While Brustein, as I have explained, depicted contemporary calls for “revolution” as little more than hubris and delusion, a number of activists had intentionally embraced theatricality in hopes of exploiting what appeared to be a historical inability to distinguish between aesthetics and politics. The Diggers, for example, were a loosely organized offshoot of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, conceived in 1966 by Emmett Grogan, Billy Fritsch, and Peter Berg as a type of performative resistance to the commercialization of the “hippie” counterculture. In opposition to the Haight Independent Proprietors (HIP), a group of merchants looking to capitalize on San Francisco’s reputation as the epicenter of the emerging youth culture, the Diggers served free food in Golden Gate Park, offered free “crash pads” for those who had nowhere to sleep but on the street, opened a free store that gave away anything from clothing and shoes to money and marijuana, and attempted to establish a free medical clinic with the help of local doctors. These services were necessary, the Diggers believed, because the HIP’s reckless promotion of San Francisco’s counterculture had brought on not a “summer of love” but a throng of runaways. There was simply no way of accommodating this swarm of homeless, penniless young men and women. The free food, clothing, and shelter the Diggers’ sought to provide, therefore, were largely designed to avert a potentially disastrous situation.4

What is important about the Diggers’ Robin Hood–style charity work—items they offered for free were often stolen from stores, delivery trucks, and so on—is the way in which they described their “social work” as a form of theater. In 1966 Berg wrote that the group’s actions were in fact a new form of dramaturgy.5 The Diggers were not, he insisted, simply offering food, clothing, and shelter, but performing a utopian future. In the essay “Trip Without a Ticket,” Berg argued that the Diggers’ brand of activism was, simply put, “Ticketless theater”: “It seeks audiences that are created by issues. It creates a cast of freed beings. It will become an issue itself. . . . This is theater of an underground that wants out. Its aim is to liberate ground held by consumer wardens and establish territory without walls. Its plays are glass cutters for empire windows.”6 For Berg, the significance of the Diggers’ guerrilla theater lay in its ability to bring about real change in real time. By collapsing the distinction between theater and everyday life, it allowed individuals to become “life-actors.” Rather than performing predetermined roles that ended with the play, actors and audience together would use their skills and imaginations to bring an alternative reality into existence. If individuals could realize this capability, Berg argued, virtually anything was possible. Social change would no longer be something that required plans and strategies; it would simply happen: “Let theories of economics follow social facts. Once a free store is assumed, human wanting and giving, needing and taking, become wide open to improvisation.”7

Frustrated not only with the marketing of “hippie” culture but also with the plodding, ineffectual political work of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Diggers took their “ticketless theater” to Denton, Michigan, in the summer of 1967 to disrupt SDS’s “Back to the Drawing Boards” conference. The seminal organization of the student New Left, SDS had planned their annual conference hoping to bridge a widening gap between the organization’s founders, who were no longer students, and its younger “prairie power” members, who had taken on active roles in local offices throughout the country, and who were far more amenable than their predecessors to the ideas of the counterculture.8 As the conference opened with Tom Hayden delivering the keynote speech, Grogan, Fritsch, and Berg burst through the door. They seized the microphone, accused SDS’s members of being more concerned with maintaining organizational structure than bringing about real social and political change, and angered the “straight” SDS’ers with their macho posturing.9 SDS was no longer the “New Left,” the Diggers suggested; the Diggers were. “You’ll never understand us,” Grogan told them. “Your children will understand us.” Then, exposing perhaps the most obvious political blindness of much of the counterculture and New Left, he called the men in the room “faggots” and “fags,” shouting “You haven’t got the balls to go mad. You’re gonna make a revolution?—you’ll piss in your pants when the violence erupts.”10 For the Diggers, SDS was, in every sense of the term, impotent. In spite of the organization’s stated desire to reassert the social and political significance of the individual, their refusal to abandon the form of a rigidly organized political movement had done just the opposite.11

As former Digger Peter Coyote has written, “Ideological analysis was often one more means of delaying the action necessary to manifest an alternative.”12 Guerrilla theater offered a way of moving beyond the inevitable difficulties of “participatory democracy” through immediate, direct action. As Grogan told the members of SDS, “Property is the enemy—burn it, destroy it, give it away. Don’t let them make a machine out of you, get out of the system, do your thing. Don’t organize students, teachers, Negroes, organize your head. Find out where you are, what you want to do and go out and do it.”13 Guerrilla theater, unlike grassroots politics, would bring about an alternative future simply by enacting it in the present. Why waste time organizing and compromising, they asked, when it was possible to “find out . . . what you want to do and go out and do it”? For the Diggers, guerrilla theater was not, as Brustein argued, a series of meaningless gestures carried out simply for effect, but the next logical step in the search for personal and political authenticity.

As one might have guessed, the Diggers modeled their guerrilla theater, at least in part, on Antonin Artaud’s “Theater of Cruelty.” According to Artaud, to be rescued “from its psychological and human stagnation,” theater must refuse to be governed by any set of preexisting texts. “We must put an end to this superstition of texts and written poetry,” he explained. Artists “should be able to see that it is our veneration for what has already been done, however beautiful and valuable it may be, that petrifies us, that immobilizes us.”14 As Jacques Derrida so famously described it, the Theater of Cruelty was designed to present “an art prior to madness and the work, an art which no longer yields works, an artist’s existence which is no longer a route or an experience that gives access to something other than itself.”15 According to Artaud, the notion that theater would defer or subjugate itself to some preexisting text or language was ludicrous. The theater was to be its own concrete language, “halfway between gesture and thought,” whose only value lay “in its excruciating, magical connection with reality and with danger.”16 While the Diggers may not have adopted Artaud’s terminology, they nonetheless believed that guerrilla theater, like the Theater of Cruelty, could only ever exist prior to representation.

The form of representation that concerned the Diggers most, though, was not the theater’s re-presentation of a written text or the psychological reduction of the therapist but the forms of mechanical reproduction that would allow their actions to be diluted and assimilated by dominant culture. Guerrilla theater was “free” because it could only ever exist in its enactment; it could be neither repeated nor commodified in the form of an image. Any attempt to reproduce guerrilla theater was destined to fail, therefore, because each performance, like those of the Theater of Cruelty, could exist only once, as an original. It was this obsession with the singularity of performance that led the Diggers to refuse to act as spokesmen not only for the counterculture but for themselves as well. When questioned about their actions, each one would refer to himself either as “Emmett Grogan,” “George Metesky,” or, more simply, as “Free.”17 To provide their own names would make them both legally and authorially responsible for their actions. As Grogan told the members of SDS assembled in Michigan, “I’m not goin’ to be on the cover of Time magazine, and my picture ain’t goin’ to be on the covers of any other magazines or in any newspapers—not even in any of those so-called underground newspapers or movement periodicals. . . . I ain’t kidding! I’m not kidding you, me or anyone else about what I do to make the change that has to be made in this country of ours, here!”18

Seeing the Diggers for the first time in Michigan, Hoffman was inspired by these ideas of direct, theatrical action. Describing his encounter with Grogan, Fritsch, and Berg, Hoffman insisted that he understood just what the Diggers meant. When he returned to New York, he began calling himself a Digger. He burned money, and opened a Free Store on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with Jim Fourratt, a political activist and former student at the Actor’s Studio.19 But there was something fundamentally different about the version of guerrilla theater that Hoffman practiced, something that truly upset the Diggers. Not long after the New York Free Store opened, the Diggers contacted Hoffman and demanded that he stop using their name. Grogan even went so far as to publicly denounce Hoffman, saying that he had simply stolen and bastardized the Diggers’ ideas.20 What Grogan failed to recognize, however, was that, for Hoffman, what made guerrilla theater powerful was less its potential to bring about an alternative reality in the present than its ability to create startling, open-ended images.

The friction between Hoffman and the Diggers seems to have begun with one incident in particular. In August of 1967 Hoffman designed a piece of guerrilla theater to be performed at the New York Stock Exchange.21 With a group of friends and reporters from local underground papers, who were there to both participate in and report on the action, Hoffman arrived at the Stock Exchange early in the morning dressed in full “hippie” regalia and requested a guided tour of the building. Security guards initially refused entry to the group, assuming, quite correctly, that they were there only to make trouble. When the guards attempted to block the door, however, Hoffman began shouting accusations of anti-Semitism, saying that their fear of hippies was only an excuse, that the real reason they were trying to turn him away was because he was Jewish. Embarrassed, the guards relented and allowed the group to pass. The guards’ suspicions were confirmed, of course, when in the middle of the tour, upon arriving at the observation deck from which visitors were able to watch the stockbrokers at work, members of Hoffman’s group pulled dollar bills from their pockets and tossed them onto the floor of the Exchange. Chaos erupted as the brokers stopped what they were doing and scrambled to pick up as many of the bills as they could. As Marty Jezer, one of the reporters in Hoffman’s group, later wrote, “The contrast between the creatively dressed hippies and the well-tailored Wall Street stockbrokers was an essential message of the demonstration. . . . Hippies throwing away money while capitalists groveled.”22

Jerry Rubin, who had met Hoffman only days before the demonstration, recalled, “Police grabbed the ten of us, dragged us down the stairs, and deposited us on Wall Street at high noon in front of astonished businessmen and hungry TV cameras. That night the attack by the hippies on the Stock Exchange was told around the world—international exposure!”23 In spite of that exposure, however, just what had happened inside the Stock Exchange was immediately shrouded in myth. No two accounts were the same. No one—including the participants—seemed to be sure how much money had been thrown, or just who had participated. When reporters asked Hoffman for his name, he told them that he was Cardinal Spellman, the Roman Catholic leader who had recently offered public support for the war in Vietnam; when asked about the number of demonstrators involved in the action, he simply said, “We don’t exist,” and burned a five-dollar bill for the camera.24 The opportunity to play games like this with reporters was just what Hoffman had hoped for in designing the action. He and Fourratt had even contacted various media outlets the previous evening and urged them to be at the Stock Exchange to witness the commotion that morning. Hoffman believed that these events, when presented in the form of a newspaper article or a story on a television newscast, would be transformed into “blank space,” one of the most useful weapons in any activist’s arsenal. Blank space, he wrote, was “a preview. . . . It is not necessary to say that we are opposed to ____. Everybody already knows. . . . We alienate people. We involve people. Attract-Repel. . . . Blank space, the interrupted statement, the unsolved puzzle, they are all involving.”25 Rather than simply telling people what to believe, actions like the one at the Stock Exchange would give them an opportunity to draw their own conclusions, to insert themselves into, or implicate themselves in the meaning of what they saw or heard. If one could use the media to broadcast those images to greater numbers, so much the better. Thus, where the Diggers looked to make themselves unrepresentable, Hoffman saw mechanical reproducibility as integral to the work of political opposition.

In part, this was because, at approximately the same time as his encounter with the Diggers in Michigan, Hoffman had begun reading the work of media theorist Marshall McLuhan. McLuhan, unlike the Diggers, praised television as the technological form that would give rise to new and radically different social forms. The way in which television presented information to the senses would drastically and irreversibly alter the forms of human interaction. Unlike the “hot” printed word, television was a “cool” medium. It offered viewers the opportunity to insert themselves into its stream of information. As a result, McLuhan argued, it would bring together vastly different cultures in a new “global village.” As he put it in perhaps his most succinct formulation, “The medium is the message”: regardless of its ostensible content, what viewers would ultimately take away from television programming was an entirely new way of engaging the world around them. Drawing on these ideas, Hoffman began to believe that media mythmaking could be used as a form of political activism. Thus, refusing to privilege the direct, personal contact that the Diggers so valued, Hoffman saw television coverage of political demonstrations as not just inevitable but valuable. Seeing viewers as active consumers of the images that entered their homes, rather than as passive receptors, allowed him to conceive of television as a potential instrument of social transformation.

At the same time, however, Hoffman’s belief in television as a revolutionary medium differed from McLuhan’s in one important respect. McLuhan believed that the social forms produced by television would be the result of a fundamental alteration of the senses: “It is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and interaction.”26 The instantaneous quality of televisual imagery would lead viewers to perceive the world in spatial rather than temporal terms, and thus to engage every facet of their lives in an altogether different way. Just how television’s potential should be used, however, McLuhan never made clear. In fact, the closest thing one finds to a prescription in Understanding Media smacks of totalitarianism: “We are certainly coming within conceivable range of a world automatically controlled to the point where we could say ‘Six hours less radio in Indonesia next week or there will be a great falling off in literary attention.’ Or, ‘We can program twenty more hours of TV in South Africa next week to cool down the tribal temperature raised by radio last week.’”27 Exposure to media could effectively “program” cultures to “keep their emotional climate stable,” he suggested, not unlike the way in which trade could be manipulated to maintain “equilibrium” in market economies. Obviously, Hoffman wanted just the opposite. It was the stable emotional climate of the United States, the “equilibrium in the commercial economies of the world,” that he found so troubling. Playing on McLuhan’s elision between two senses of the term “cool,” Hoffman wrote, “Projecting cool images is not our goal. We do not wish to project a calm secure future. We are disruption. We are hot.”28 Thus, while he looked to McLuhan’s work for the idea that television might play a role in bringing about a new “global village,” Hoffman’s idea of how television would be used to bring that village into existence differed greatly. For Hoffman, the medium and the message were far from inseparable. Although he sought to use television to broadcast his message, that message, ultimately, was a critique of the images television offered.

According to Hoffman, televisual images of the counterculture would never revolutionize society by “cooling off” a potentially dangerous situation. Rather, he argued that they would work by establishing a figure-ground relationship with other images on TV. As he put it, “It’s only when you establish a figure-ground relationship that you can convey information.”29 Footage of “monkey theater,” as he came to call his own version of guerrilla theater, would necessarily interact with, and stand out against, the background formed by more predictable scenes. If these images were outrageous enough, Hoffman believed, viewers would be unable to ignore or dismiss them, regardless of what commentary might be offered to frame or explain them. For this reason, he considered nightly news coverage of monkey theater to be something akin to an “advertisement for the revolution.” Images depicting hippies tossing money onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange would convey information much like the most persuasive images on television: commercials. Discussing the news program Meet the Press, Hoffman wrote, “What happens at the end of the program? Do you think any one of the millions of people watching the show switched from being a liberal to a conservative or vice versa? I doubt it. One thing is certain, though . . . a lot of people are going to buy that fucking soap or whatever else they were pushing in the commercial.”30

Advertisements were figures standing out from the ground that was the regularly scheduled program. They were designed to be quick, to the point, and to capture the viewer’s imagination. To function like an advertisement emerging from the middle of a newscast, therefore, protestors would have to distance themselves from any form of rational debate. Engaging in calm, orderly discussions about substantive issues was the manner of politicians, and, not coincidentally, of organizations like SDS. To Hoffman, any attempt to achieve political change in this fashion seemed doomed to failure: even if one managed to be included in nightly news broadcasts, the chances that what one said would change anyone’s mind were slim. No one “switched from being a liberal to a conservative or vice versa” after watching Meet the Press. Showing, for Hoffman, was completely different from saying—but not in the way that the Diggers had insisted. To be effective, guerrilla theater had to be flattened out, treated, quite literally, as an image: “What does free speech mean to you? To me it is an image like all things.”31 Attention to the form of one’s actions was necessary not because those actions had the potential to bring about a new reality, or because one wanted to “speak truth to power,” but because political opposition had become inextricable from practices and modes of representation. For this reason, monkey theater would assume a very specific form. After all, the actions of private citizens only received national attention when they were in some way sensational. Monkey theater, then, would have to be literally spectacular. In looking to make protest newsworthy, that is, the appearance and mannerisms of those who had already been deemed newsworthy would have to be adopted. Monkey theater would have to speak reporters’ language. As Pierre Bourdieu would argue thirty years later, “You have to produce demonstrations for television so that they interest television types and fit their perceptual categories.”32 Monkey theater, in other words, would have to look like a “revolution”; it would have to conform to television reporters’ conception of an uprising.

Following the events staged at the Stock Exchange, Rubin, captivated by Hoffman’s media savvy, invited him to aid in the organization of an upcoming demonstration sponsored by the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (Mobe). David Dellinger, the head of the Mobe, had enlisted Rubin’s help that summer, after Rubin’s bid to be elected mayor of Berkeley, California, had failed. Although he lost the mayoral race, Rubin’s knack for publicity and his ability to appeal to young people seemed, to Dellinger, just what the Mobe needed. Dellinger was seeking to bring vast numbers of protestors to Washington, DC, in October for a national antiwar demonstration. He asked Rubin to take charge of the project, hoping that Rubin would be able to deploy the creative political tactics for which he had become known in Berkeley on a national stage. By appealing to those youths who might otherwise have been reticent to take part in one of the Mobe’s more conventional actions, Dellinger hoped to assemble the largest antiwar demonstration to date. With Hoffman and Rubin composing the script, however, what was initially conceived quite literally as the antiwar movement’s March on Washington became instead another work of monkey theater.

The event, as they saw it, might begin with a march, but that march would end south of the Potomac in a massive act of civil disobedience on the grounds of the Pentagon. Dellinger protested, explaining that authorities would simply have to block the bridge leading out of Washington and their plans would be ruined, but Rubin and Hoffman were undeterred. It was essential that the demonstration engage the Pentagon, Rubin explained, for it was “a symbol so evil that we can do anything we want and still get away with it.” Thus, “Our scenario: We threaten to close the motherfucker down. This triggers the paranoia of the Amerikan government: The Man then organizes our troops for us by denying us a place to rally and march. Thus just-another-demonstration becomes a dramatic confrontation between Freedom and Repression, and the stage is the world.”33 To announce the event, Rubin and Hoffman called an official press conference on August 28. As Rubin explained, their performance was to “grab the imagination of the world and play on appropriate paranoias,” ensuring that no one would be able to ignore or forget their threats and promises in the weeks leading up to the protest.34

They assembled an appropriate cast of characters. David Dellinger and Bob Greenblatt were there as official representatives of the Mobe. Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory was also invited, as were, Rubin recounted, “a Vietnam veteran, a priest, a housewife from Women Strike for Peace, a professor, an SDS leader,” and “Amerika’s baddest, meanest, most violent nigger—then H. Rap Brown,” who, “whether or not he even showed up at the Pentagon, would create visions of FIRE.”35 As menacing as Brown may have seemed, however, it was Hoffman who stole the show. He wore an old, unbuttoned army shirt and introduced himself as Col. Jerome Z. Wilson of the Strategic Air Command, telling reporters that he had recently deserted because of “bad vibrations.” On the day of the protest, he said, Washington’s famed cherry trees would be defoliated, the Potomac River would be dyed purple, and marijuana, which had already been surreptitiously planted on the lawn of the Pentagon, would be harvested. Moreover, he explained, as a grand finale, demonstrators would stand side by side, holding hands and chanting in a circle around the Pentagon. The importance of the circle, he explained, was that a ring of humans joining hands would cause the Pentagon to rise from the ground, and would force the evil spirits inhabiting the building to fall out. The warmongers were to be vanquished by a demonstration of countercultural “love” and “spirituality.”

Of course, Hoffman never believed that protestors would be able to levitate the Pentagon. On one hand, the claim was about numbers: the idea of the number of bodies necessary to form a circle around the Pentagon would in itself make the upcoming demonstration seem enormous. On the other hand, the exaggerated and farcical reference to a kind of mystical spirituality emblematized a number of stereotypes regarding hippies and the counterculture. Describing his motives for the claim, Hoffman wrote, “The peace movement has gone crazy and it’s about time. Our alternative fantasy will match the zaniness in Vietnam.”36 The outlandishness of this alternative fantasy would allow neither reporters nor viewers to ignore it. It would be so incredible, in fact, that it would stand in relief against the background of daily news footage from Vietnam, which, though often horrific, had become commonplace. Against this ground, Hoffman would attempt to broadcast a figure of “revolution.”

In the days following the press conference, the story of the Pentagon’s potential capture by hippies practicing a type of angrily joyful mysticism took on a life of its own. The Washington, DC, police department issued a formal statement saying that they were prepared, should the demonstration get out of hand, to use Mace to temporarily blind protestors. In response, Hoffman issued a statement of his own, claiming that hippie scientists had developed a new sex drug called Lace. “Lace is LSD combined with DMSO, a skin-penetrating agent,” he announced to the press. “When squirted on the skin or clothes, it penetrates quickly to the bloodstream, causing the subject to get sexually aroused.”37 For those who doubted his claims, Hoffman and friends staged an orgy. Reporters were told to meet at his apartment for proof of the drug’s existence. Upon their arrival, Hoffman delivered an introductory speech “full of mumbo-jumbo,” and then asked a number of “test subjects” to proceed with a “demonstration.” “The subjects shot themselves with water pistols full of purple Lace, took off their clothes, and fucked. Then they put their clothes back on, and the reporters interviewed them.”38 Within days the media was abuzz with rumors and questions about the new sex drug. As Hoffman later said, “People suspected the Lace demonstration was a put-on, but then again. . . . Hippies, drugs, orgies: it was perfectly believable.”39 Hoffman knew that in some sense the viewing public saw the counterculture as little more than a hypersexualized form of youthful rebelliousness. But rather than attempting to correct that impression, he seemed to delight in reinforcing it.

Not surprisingly, his willingness to enact these negative stereotypes for the mainstream press drew the ire of more than one critic. In his 1968 text The Making of a Counter Culture, Theodor Roszak lambasted Hoffman for promoting a debased version of “cultural revolution.” For Roszak, Hoffman’s association with the counterculture was nothing more than the result of a series of misunderstandings. The “true” counterculture, he believed, would never have “performed” for the media. To the contrary, for those who understood and shared the counterculture’s dissatisfaction, the media merely offered proof of the soullessness of contemporary society.

For Roszak—and, he argues, for members of the true counterculture—the media were ultimately symptomatic of the larger problem facing America in the mid-twentieth century, the problem of “technocratic” thought. The flood of information that confronted people in their daily lives had qualitatively transformed experience. Individuals had been subordinated to technology, categorized as sets of facts subject to specialized knowledge, and thus alienated from themselves: “In the technocracy everything aspires to become purely technical, the subject of expert attention.”40 Individual desires had been commodified and subsumed within the technocratic social order. Life, as a result, had come to seem like a parody of itself. For the first time in history it had become possible for people to believe that “real sex . . . is something that goes with the best scotch, twenty-seven-dollar sunglasses, and platinum-tipped shoelaces.”41 At the same time, though, this technocratic society carried within it the means of its own dissolution. The advanced education necessary to produce specialists in various technical fields had also equipped students with the ability to think critically about the sociohistorical conditions that necessitated such specialized knowledge. Recognizing the relationship between this highly specific knowledge, on one hand, and their own intense psychic and social alienation on the other, many of those who were to become the technocracy’s future leaders began to rebel. According to Roszak, therefore, if one hoped to understand the counterculture it was essential to understand the work of Herbert Marcuse, for it was precisely this psychosocial alienation that Marcuse had, in the mid-1950s, so cogently diagnosed.