Читать книгу Free The Children - Craig Kielburger - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

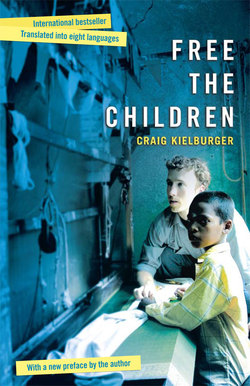

ОглавлениеPREFACE

It has now been more than a decade since I first learned about the life and death of child rights activist Iqbal Masih and embarked on a journey that would forever change my life. It all started with one bold headline: “Battled child labor, boy, 12, murdered.” As a Grade 7 student from a middle class suburban neighbourhood, I was shocked to discover these words glaring back at me from the front page of the newspaper one morning. This, my first encounter with injustice as experienced by a child like myself, dramatically changed my ideas about the world. More importantly, it made me realize the world had to change.

In the beginning, Free The Children was little more than a small group of classmates eager to raise awareness about child labour. None of us had much experience with social justice work—just a desire to take action. Having discovered that children around the world were being forced to work in terrible conditions, toiling away day after day without the hope of going to school, we became determined to work toward change. While striving to free children from poverty and exploitation, we also sought to free our peers—and ourselves—from the idea that we were too young to make a meaningful difference in the world.

At the time, youth activism had yet to come into its own. A more broadly inclusive approach to children’s issues had yet to appear on the agenda, let alone become a priority. Children’s interests were almost always represented by adults, and young people’s voices were rarely acknowledged. In those days, the idea of children helping children was practically unheard of. As children speaking out on children’s rights, we were an oddity. While our families and friends were always there to cheer us on, others were generally skeptical about what we could accomplish. In the early days, few decision-makers were willing to listen to what we had to say, and fewer still were supportive. With adults unwilling to get involved, we began to make connections with the one group of people we knew would understand: other young people.

Excited at the prospect of making a difference in the world, children and youth flocked to our organization. With this influx of energy and creativity, Free The Children was able to expand the scope of its activities. Soon, we were speaking to groups across the country, and people were beginning to listen. All our hard work began to pay off as more and more people started to pledge their support.

It was around this time that I first got the idea of travelling to the developing world. I knew that if we were to help child labourers, we needed to learn from the children themselves. Of course, I didn’t yet have any idea how to arrange a trip like this, let alone convince my parents to let me travel halfway across the globe. I just knew that this was something I had to do.

My trip to South Asia was to mark a significant turning point in my role as a children’s rights activist, as this account of my adventures makes clear. During my journey through Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Nepal and Pakistan, I had the chance to witness children’s challenges first-hand. I had left home expecting child labour to be something secret and hidden, but to my surprise nothing could have been further from the truth. Working children were everywhere, and eager to talk to me about their experiences. Kids nearly half my age told me that they had no choice except to work. Time and time again they explained how hard they struggled, hoping for a better future. I was in awe of their courage. Often, I felt frustrated by how little I could actually do to help my new friends. Slowly, I came to realize that the one way I, a twelve-year-old from Canada, could really make a difference was by sharing their stories. I could return their friendship by making certain they would never be forgotten.

While travelling in South Asia I came to understand that child labour is both a cause and consequence of poverty. I began to see that it wasn’t enough to simply be against child labour when children and their families were desperately in need of basic necessities and new opportunities. It was then that I first came to understand that freeing children means more than ensuring that no child be enslaved: it means empowering young people and their families. By the end of my trip, it had become clear that Free The Children had a lot of work to do.

In the early 1990s, the World Summit for Children and the Declaration on the Rights of the Child had promised to usher in a new era in the protection and promotion of children’s rights. Over the course of the decade, child labour made its way onto the international agenda, and the world became willing to address a number of issues that had for years been swept under the rug. By the time Free the Children was first published in 1998, our organization had become much larger than any of us would have imagined. Youth in Action Groups had begun to spring up all over the world. We had plunged into development work, building schools and establishing alternative income programs in a number of countries in the developing world. Young people were becoming more and more aware of their power, and were beginning to use it to help their peers around the world.

It was an exciting time filled with many important firsts, both for our organization and children everywhere. Free The Children India organized a rally to protest the kidnapping of handicapped children in West Bengal who were being forced to work as beggars and drug runners to Persian Gulf countries. As a result, the Indian government promised to put a stop to this practice. Fourteen-year-old Daniel Strand and the young people of Free The Children Brazil helped to convince the Brazilian government to invest more than one million dollars in projects to alleviate child labour in Salvador de Bahia. Of course, in other cases it was clear that promises to the world’s children were easier made than kept. We learned a lot during those years, and Free The Children continued to expand the scope of its activities. At the time, however, even we could not have imagined how our organization would evolve.

Over the past twelve years Free The Children has grown into the world’s largest network of children helping children through education. Whereas we used to work out of my parents’ garage, our Toronto office now occupies an entire building on the city’s east side. My older brother Marc—now a Harvard graduate, Rhodes Scholar and Oxford-educated lawyer—acts as a mentor to all of us at Free The Children in his role as chief executive officer. While we still depend on the efforts of our dedicated volunteers, we now work with a team of full-time staff who strive to empower young people everywhere to create positive social change.

Education, always at the centre of our work, has taken on new importance over the years. We are now committed to educating people about a variety of issues that impact children and youth, and to enable children around the world to benefit from primary education. Fundraising campaigns led by over a thousand Youth in Action groups have helped build more than 500 schools in developing nations, bringing education to more than 50,000 children every day. Our alternative income projects now empower more than 22,500 families. Our many accomplishments in the areas of education, alternative income, health care, water and sanitation provision and peacebuilding have earned us three Nobel Peace Prize nominations and facilitated successful partnerships with organizations such as Oprah’s Angel Network. To date, we have changed the lives of more than a million young people in forty-five countries around the world.

For all that our organization has grown, there are many things that haven’t changed—and never will. We remain as determined as ever to build a better world, and still live this commitment through projects planned one at a time.

As for me, I’ve managed to balance speaking engagements and fact-finding missions, while also completing an undergraduate degree through the University of Toronto’s Peace and Conflict Studies program. My travels continue, as I regularly visit our many projects in developing nations and check in with the Youth in Action groups throughout North America and beyond.

In some ways I think I experienced the luckiest childhood in the world. My supportive parents and great friends allowed me to gaze at the sky and see no limits. I’ve had the opportunity to travel to more than fifty countries and meet extraordinary world leaders like the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa and Pope John Paul II. I’ve been able to work with amazing social activists and explore fascinating cultures and traditions. Most importantly, I’ve have the chance to spend time with children living in some of the world’s furthest extremes of poverty, and draw inspiration from their hope for a better life.

Some, like Suzanne, struggle to survive the horrors of war. When I first met Suzanne in Sierra Leone, she quietly explained how, during her country’s decade-long civil war, she and her sister had been taken prisoner by a rebel commander and forced into a life of servitude. Liyane, who I came to know during a recent visit to Sri Lanka, is now struggling to care for her brothers and sisters after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami swept their parents out to sea. The Bedouin children I met in the Negev desert were trying to find a way to continue their schooling. Several of these children told me that many “important” people had come to visit them accompanied by the media, and promised to send them computers—which never arrived. They begged me to send them some pencils to use at school. I’m proud to say Free The Children has touched the lives of all these children, and I’m forever grateful for all that they have taught me in return.

Today, I am still driven by the commitment I made on my first trip to South Asia: to ensure that the plight of the world’s children will never be forgotten. Over time, I have come to understand that this commitment must involve not only raising awareness about the challenges facing young people and providing opportunities for children in the developing world, but also empowering a new generation of social activists. Excited at the prospect of helping the next twelve-year-old who reads a newspaper and is motivated to take action, we began to launch one idea after another: workshops, camps, manuals, speaking tours, volunteer trips abroad. This was the beginning of a youth leadership training organization, now known as Me to We, dedicated to empowering young people to create positive social change. Our name for the new organization grew out of the concept of bringing change in our daily choices by moving collectively towards living as a we generation. Having witnessed the efforts of young people across the globe to spearhead social change, we felt it was time to emphasize that we can all make a difference in our world right now.

Since 1999, Marc and I have been able to put a lot of our ideas about youth empowerment to the test. Through Me to We’s programming, ten of the twelve largest school boards in Canada are currently helping students fulfil their mandatory service requirements while making positive contributions to their communities. Our summer leadership training camps, learning resources and speaking tours continue to engage 350,000 kids across North America annually. Every year, more than a thousand young people embark on volunteer trips to our projects in places like rural China, Kenya, India, Mexico and Ecuador. They work to help local communities while enjoying the eye-opening experience of exposure to new cultures—just as I had my own life so dramatically changed on my first trip to Asia. Despite all-too-frequent charges of youth apathy, young people today do have the power to create positive social change—and they’re using it!

People sometimes ask us how we maintain our optimism amid so many challenges—injustice and deprivation, the scourge of AIDS and the devastation of war. We respond that it is often in the midst of these horrors that we find the greatest virtue. We have seen teachers spending their own money to help at-risk students in inner-city schools, aid workers toiling to the point of exhaustion to help people in refugee camps and mediators risking their lives in war zones in order to secure peace. In places plagued by hunger, suffering and despair, we have seen people coming together to help one another, sharing what little they have, and celebrating the small pleasures allowed to them. Witnessing such extraordinary acts of courage, we have come to appreciate the importance of community and caring, and to understand the true reaches of human potential.

Marc and I are frequently invited to speak at motivational seminars and conferences where people gather to discuss paths to happiness and fulfillment. All too often, we have found ourselves sitting on panels with people proposing quick and easy solutions to people’s problems. The more we’ve listened to them celebrate power and money, however, the more we’ve begun to see that their “solutions” conflict with much of what we’ve learned in our service work, both at home and overseas.

Through our travels, our diverse experiences with social involvement, and the opportunity to meet and learn from some our greatest heroes, Marc and I have discovered the most surprising thing: in setting out to change the lives of others, our own lives have changed. In learning about the different people and cultures that we have encountered, we have come to re-examine our most basic assumptions about the world and our place in it, and emerged with a clearer understanding of what it takes to build a better world—and lead a fulfilling life.

We have gradually arrived at a different way of thinking, and a different way of life that we like to call Me to We. Me to We involves focusing less on “me” and more on “we”—our communities, our nation and our world as a whole. It is about living our lives as socially conscious and responsible people, engaging in daily acts of kindness, building meaningful relationships and communities and considering the impact on “we” when making decisions. Basically, it represents a change in focus, a shift from the inside out.

I know that this is the change that began somewhere deep inside me when I first read about Iqbal and realized the comfortable North American lifestyle I enjoyed was the exception rather than the rule. Since then, with each decision I’ve made to learn more about the world, and each attempt I’ve made to change it—whether by speaking out, working with Free The Children or empowering young people through Me to We—I’ve become more and more committed to this way of life. In becoming involved in the struggle for children’s rights and youth empowerment, I’ve learned first-hand how all of our actions have incredibly important consequences for those around us, both next door and halfway around the world. In the process, I have come to understand that the challenges we face are collective ones, and that all of our victories are shared.

Be The Change,

Craig

Toronto, July 2007