Читать книгу The Green Rolling Hills - Craig Tucker S. - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

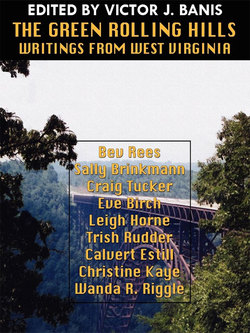

ОглавлениеMETAMORPHOSIS, by Bev Rees

A large-boned woman, with a rather handsome face, stood admiring the display strewn across the drain board. Golden carrots with lacy tops intact. Dark green kale. Three waxy red tomatoes and a flawless purple eggplant. Encouraged by the silence, a wall clock ticked the seconds forcefully. A portly orange tomcat, exhausted by a night of love, padded into the kitchen. He rubbed against the woman’s legs. She glanced down at him and smiled. “Does Valentino want his breakfy?”

An avid gardener and sometime painter, Kitty Smallwood had always liked the idea of vegetables. Fruits and vegetables artfully arranged. She painted mostly for her friends, gifts for their lovely Connecticut kitchens; country kitchens designed by interior decorators. Exquisite little paintings that sold well at county fairs and church bazaars. It never went any further than that, though everyone agreed she had a talent for it. The truth was, Kitty had absolutely no ambition, and consequently did not apply herself.

As soon as the crocuses poked through, and the air took on that soily-mulchy fragrance, Kitty abandoned her brushes. It was mucking about in the garden she loved most. She’d make tiny depressions in the rich dark loam, and gently set in the baby lettuces she had started under glass. She’d pull the soil up carefully around their tiny necks, much like tucking them in bed, she often mused.

* * * *

Kitty’s life was secure and comfortable. A large Cape Cod, circa 1880, several cats that liked to sit on laps, and a cheerful golden retriever named Geraldine. And, well-screened from cranky neighbors and their silly zoning laws, five gorgeous Hampshire hens. Though a vegetarian, she justified the eating of those lovely pale brown eggs. It somehow seemed so natural. Besides, she reasoned, if nobody ate eggs, those charming feathery creatures would cease to be, and that to her mind, would be unacceptable.

In her youth she had been, I guess you’d have to say it, a hippie. It came so easily to her. The peasanty costumes, the free flowing locks, the trekking around Nepal with a backpack. And all that lovely pot, yes, she remembers that, and numerous sexual encounters deeply buried in her psyche. Secrets she thought prudent to keep well hidden, even from herself.

But that was then, and now was now, and it was permissible to wear her graying hair in one long braid in the garden. And as freewheeling as she was by nature, she was not altogether dismissive of current expectations. Consequently, every day at four or so, her muddy overalls got relegated to the potting shed, and after a leisurely scented soak she donned the compulsory low-slung jumper and a pair of Swedish clogs. She then disciplined her hair into a kind of upward backward twist, resembling a fresh baked challah. Most of her acquaintances––it would be false to call them friends––wore their hair in pricey cuts. And though they were somewhat amused at Kitty’s old-fashioned notions, they were largely tolerant. And soon she’d hear Ben come up the driveway, the wheels crunching yellow gravel. Everything so safe, so predictable, as through the door he’d come with: “Where’s my Kitty Cat?”

The most objectionable thing about Ben was his carnivorous nature. Oh, she had known, she had known. Foot long hot dogs smothered in mustard, raw oysters by the dozen throbbing still with life, and oozing prime rib, barely warmed. She excused all this because he was, by God, a dentist. No longer young, that’s true, but still attractive.

And Kitty? She had been a recovering hippie at that time, dabbling around in interior decoration. And, as luck would have it, Ben walked into the fabric shop one day and became absolutely besotted with her freckled easy-going ways; perhaps because she was the direct opposite of him in almost every way. Feeling that her prospects were anything but stellar, she decided she had better go for it.

The first three years they lived in a rather swell apartment on the upper West Side of Manhattan, and it damn near suffocated her. Hadn’t she warned him she was not a city girl? When she became downright despondent, he said, “All right, Kitty, go out to the suburbs and find something nice. But please, not Jersey. That’s too close to my brother Jerry.”

She found a lovely old Cape Cod, long neglected, and Ben spent a pile pulling it together––and here she was giving him his daily peck on the cheek. Soon the barbecue would be fired up for his half pound of flesh, and she would arrange the steamers for her veggies, and life was so peaceful, wasn’t it––and dry martinis in the pleasant garden. Not to mention her gleaming perfect teeth.

Kitty spent her days deadheading roses, and in winter she and Geraldine took long snowy walks, and basically, that’s all she needed. The talk of children never intruded on their conversations, perhaps because Ben thought it was too late in the day to start a family. And possibly because he was so awfully busy.

That was just fine with Kitty. She had never pictured herself burping squalling babies and wiping tender bums. Her mother seemed to have detested children. Come to think of it, her mother seemed to have detested her. So Kitty figured, at times a little wistfully, that no maternal genes had passed her way. Any stirrings in that direction had been promptly buried next to her youthful indiscretions.

And Ben? What he needed was a wife, a replacement for a former one. Someone there when he came home. Someone who appreciated his substantial paycheck and didn’t complain about his evenings locked away with his rare coin and stamp collection. Someone by his side at office parties, cooperative in bed, but not too demanding. And by all accounts they suited each other perfectly.

* * * *

Then one fateful night, when the frogs were croaking like an ancient chorus, the telephone shattered life as they knew it.

“Jerry’s dead,” Ben announced, his face as white as flour.

“What?”

“My brother Jerry. He’s dead.”

“Oh dear God! I can’t believe it. Who called?”

“Silverman. Along the Palisades Parkway. Apparently he was speeding, lost control, crashed into a guardrail and flipped. But Christ, he had to have that damn high-powered Ferrari, didn’t he?”

“Oh Ben, how awful. How very awful. But where’s Paul?”

“Paul’s with Esther, Kitty. He’s with Esther.”

* * * *

Ben kept putting off a discussion about Paul. Finally, on the way to the funeral, at the eleventh hour so to speak, he was forced to muster up some courage.

“Kitty Cat, you understand, I will have to see to Paul.”

“What do you mean––see to?”

“Well, the truth is he has nowhere to go now, does he? You know the situation.”

Kitty’s heart sank. “I thought you said he was with Esther.”

“Sweet Baby, you and I both know he can’t stay with Esther. Didn’t I tell you just last week? She’s been searching for a retirement home for some time now. Oh Kitty Cat, why don’t you ever pay attention? You know full well she can hardly manage on her own. In any event, Esther is too old and too fragile to take on a thirteen-year-old boy.”

Her pulse danced wildly on her wrist. “Who’s going to take him?” she asked.

“He’s my nephew, Kitty, my only nephew.”

“Perhaps a good boarding school then?”

“No, Paul’s been through an awful lot. He’s the kind of kid that does not do well without a mother. He’s rather fragile and needs a good deal of support.”

“Oh no, Ben. Oh no, oh no. I don’t know a damn thing about mothering. I don’t know a damn thing about adolescents. In fact, I was a lousy adolescent; everybody said so. How could I be of any help to him? Besides, it will all fall on me, every damn bit of it. When are you ever available, I’d like to know? Please Ben, please. I don’t want this in my life.” Hysteria was forming in her throat. “I just can’t do it,” she screamed. “I just can’t do it!”

“Oh, Kitty, Kitty. You’re putting me between a rock and a hard place. There are things in life one has to do,” he said calmly. “Like it or not––this is one of them.”

* * * *

Paul came up the walk lugging two bulging backpacks and an exhausted looking Teddy bear. A tall gangling sort of boy with an angry complexion, and sad gray eyes. Kitty managed a chirpy welcome. He responded with a growl, and dropped his backpacks by the stairs. She took him up to his room. A lovely room that looked out on mostly hardwoods. When she pointed this out to him, he disdainfully glanced out the window. And it was quite clear to Kitty––he would have been just as happy with a slag heap.

Mealtimes became stressful. The easy banter between husband and wife soon evaporated. Ben bent over backwards in an effort to make conversation. Paul’s responses were limited to shrugs and monosyllables. He spent his meals hovering over his food, pushing it this way and that, scowling, as if suspicious they might attempt to poison him.

Paul lolled about listlessly for a week or so, and Ben, not knowing what to do, enrolled him in the local junior high school. His first day there, Kitty spent pacing up and down. She agonized about her fate and obsessed on their future, which at the moment appeared to be black as pitch. At four o’clock she could hardly breathe as she waited for him to walk up from the bus stop.

When he walked through the door, her fingers were tightly crossed behind her back. She said, “How was it?”

“Shitty,” he said. He climbed the stairs and slammed the door behind him.

Kitty’s heart sank. It was already May. How was she ever going to get through the summer? How was she going to endure three sultry months of Paul lying around, flipping channels and drinking endless colas? She begged Ben to send him to a nice camp, up in the Poconos, maybe, or how about Vermont? Ben diplomatically approached him. The boy’s answer was a resolute, “Fuck camp.”

“Are you going to allow him to talk to you like that, Ben?”

“We’re going to have to be patient, Kitty. Please remember he’s a kid whose mother abdicated her responsibility early on. In many ways, I suppose, he sees himself as an abandoned child. From what you’ve told me about your mother, I would think you might be able to understand that. And Jerry, well, you knew Jerry. His heavy drinking, an endless string of housekeepers, not to even mention his numerous female attachments. You couldn’t exactly call it a structured home life, could you? And now––his father dies in a car crash. Be fair, Kitty. This isn’t easy.”

* * * *

In mid-May Mr. Chandler came around and rototilled, but Kitty felt too paralyzed to plan a garden. Meditation proved impossible. Deep breathing didn’t help. The whole house seemed to be engulfed in an atmosphere of gloom. As May drew to a close she began to realize she would have to take refuge in her garden, or be strangled by her own relentless rancor.

Then one late June morning, when she was down on her hands and knees, tucking soil around some baby lettuces, a shadow cast itself across her busy hands. Startled, she looked up and saw Paul standing there and, eying a hoe lying by her side, a grisly thought flitted through her mind: Oh God, he’s going to try to kill me.

“What are those?” he said.

“Lettuces,” she sputtered. “Little innocent baby lettuces.” She feared she might have to defend them from his flip-flops.

“Beautiful,” he said.

“What?”

“How long before they’ll be ready to eat?”

Glory Hallelujah, he actually formed a sentence. “Not long at all. Would you like to set in the rest of the row?” she asked, as she tried to still her quivering hands.

“Yeah, sure. I got nothin’ better to do.”

And oh, his hands––those elegant long fingers so gentle as he caressed the tiny plants and tucked the earth around them. And how beautiful his straight and strong young back, as he hovered over them.

“You want to do a row of peppers, Paul?”

He also did two rows of tomato plants and a row of cucumbers.

“Well,” said Kitty, more calm now. “It’s well past noon. You don’t by any chance like salads, do you?”

“You don’t, you know, eat meat, do you?” Paul said.

“No, not for twenty years. Not since I lived in a commune in California.”

“You lived in a commune in California? Cool. I don’t like meat either. My father ate raw steaks. It used to make me want to puke.”

“Well, nobody’s making you eat meat here, Paul.”

“Yeah, but Uncle Ben fires up the grill every single night. I don’t want to, you know, offend him or nothin’. See, when I was a little kid we hit a deer. My father, as usual, was speeding, and it splattered all over the place. There was blood and bits of flesh all over the hood and windshield. And I will never forgot those terrified eyes as he lay there dying. It actually made me sick. I know it’s stupid, but no matter how I try I can’t get rid of it. My father even sent me to a shrink, but no go. Every time I face a piece of meat I think of that poor animal.”

“Oh, that’s all right, Paul, he doesn’t care,” Kitty said. “We learned years ago, the hard way, that we had to respect each others’ peculiarities or call it quits.”

They stood at the kitchen counter, shoulder to shoulder. They peeled, chopped, grated, and sliced. They mashed avocados and squeezed lemons.

When Paul had swabbed up the remainder of the vinaigrette dressing from his bowl, he said, “You gonna eat what’s left on the counter?”

The next thing Kitty knew she was seated on the sofa with Paul’s body slumped across her lap. His tears flowed freely, falling on her overalls. He sobbed, he truly sobbed––and she had never felt so elated in her entire life. She had a strong inclination to stroke his hair, but hesitated, fearing he would jump up and scream “fuck off.” But she was overcome by an unaccustomed tenderness, and touched his head ever so lightly, surprised to see that it seemed to comfort him. She proceeded to stroke his head, like she stroked and patted Geraldine.

Is this how a mother feels when they hand her that first newborn? Some unaccustomed feeling, noble and unselfish was welling up inside her.

After awhile Paul sat up, looking horrified. “Sorry,” he said, “Oh God, gees, I’m really sorry.”

“No, no, don’t feel sorry. You don’t have to feel sorry.”

And before long they were sitting shoulder to shoulder on the porch swing, mulling over Kitty’s seed catalogs.

“It’s never too early to plan for next year,” she said. “And Paul, who knows? Maybe between us we can convert your uncle Ben, and get rid of that nasty old grill altogether.” She began feel all swoony, like you feel when you are falling in love.

And for the first time since he arrived––Paul smiled at her.