Читать книгу Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret - Craig Brown, Craig Brown - Страница 20

14

Оглавление‘We are born in a clear field, and we die in a dark forest,’ goes the Russian proverb. For fifteen years – from the age of two to seventeen – Princess Margaret was looked after by a governess, Marion Crawford; for both of them, this was their clear field.

Marion Crawford – always known to the Royal Family as ‘Crawfie’ – was born in Ayrshire in 1909. She studied to be a teacher, with the aim of becoming a child psychologist. She wanted to help the poorest members of society, and ‘to do something about the misery and unhappiness I saw all around me’.

But a chance meeting diverted her from this calling. The Countess of Elgin asked her to teach history to her seven-year-old son, Andrew. Crawfie became the victim of her own success: impressed by her teaching skills, the Countess persuaded her to stay on to teach her other three children, and then recommended her to Lady Rose Leveson-Gower, who was after a tutor for her daughter Mary. Mary later remembered Crawfie as ‘a lovely country girl, who was a very good teacher’.

And so the ball was set rolling. In turn, Lady Rose recommended her to the then Duchess of York, who needed a governess for her little daughters Princess Elizabeth, aged five, and Princess Margaret Rose, aged two.

The interview went swimmingly. Crawfie found the Duchess of York the homeliest of women. ‘There was nothing alarmingly fashionable about her,’ she recalled. ‘Her hair was done in a way that suited her admirably, with a little fringe over her forehead.’ Royal historians have credited, or discredited, Marion Crawford with obsequious, saccharine observations, but that initial view of her future employer surely has a sharp edge to it, with its needle-like suggestion of frumpiness.

The Duchess sat plumply by the window at that first meeting: ‘The blue of her dress, I remember, exactly matched the sky behind her that morning and the blue of her eyes.’ It’s an eerie image, suggesting a disembodied royal, her dress merging into the sky, and with holes where her eyes should have been.

So Crawfie was taken on as governess, and moved into 145 Piccadilly, the London residence of the Duke and Duchess of York and their two little Princesses. After a day or two, she was presented to His Majesty King George V. In a loud booming voice – ‘rather terrifying to children and young ladies’ – the King barked, ‘For goodness sake, teach Margaret and Lilibet to write a decent hand, that’s all I ask you. Not one of my children can write properly. They all do it exactly the same way. I like a hand with character in it.’

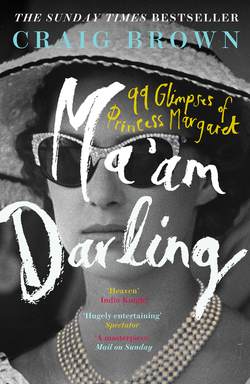

(Bettmann/Getty Images)

On her arrival, Crawfie had been aware of a widespread rumour that little Princess Margaret Rose was rarely seen in public because there was something wrong with her. ‘One school of thought had it that she was deaf and dumb, a notion not without its humour to those who knew her.’* The rumour was eventually dispelled by news of a bright remark the little Princess had made over tea at Glamis Castle with the playwright J.M. Barrie. Barrie had asked Margaret if a last biscuit was his or hers. ‘It is yours and mine,’ replied Margaret. Barrie inserted the line into his play The Boy David, and rewarded Margaret with a penny for each time it was spoken onstage.

From the start, Crawfie found her two charges very different. Elizabeth was organised, Margaret artistic; Elizabeth discreet, Margaret attention-seeking; Elizabeth dutiful, Margaret disobedient; Elizabeth disciplined, Margaret wild. ‘Margaret was a great joy and a diversion, but Lilibet had a natural grace of her own … Lilibet was the one with the temper, but it was under control. Margaret was often naughty, but she had a gay bouncing way with her which was hard to deal with. She would often defy me with a sidelong look, make a scene and kiss and be friends and all forgiven and forgotten. Lilibet took longer to recover, but she had always the more dignity of the two.’

The relationship between the two little Princesses was already set. ‘Lilibet was very motherly with her younger sister. I used to think at one time she gave in to her rather more than was good for Margaret. Sometimes she would say to me, in her funny responsible manner, “I really don’t know what we are going to do with Margaret, Crawfie.”’

Margaret’s Christmas present list for 1936 – their first Christmas in Buckingham Palace – shows how the elder sister took the younger in hand. Lilibet, aged ten, wrote it to remind Margaret, aged six, who would be expecting Thank You letters from her, and for what.

See-saw – Mummie

Dolls with dresses – Mummie

Umbrella – Papa

Teniquoit – Papa

Brooch – Mummie

Calendar – Grannie

Silver Coffee Pot, Clock, Puzzle – Lilibet to Margaret

Pen and Pencil – Equerry

China Field Mice – M.E.

Bag and Cricket Set – Boforts

China lamb – Linda

Far from being wholly anodyne, Crawfie’s memoir, The Little Princesses, is peppered with intimations of a perilous future for Margaret. Did Lilibet also sense that her younger sister might be in for a bumpy ride? ‘All her feeling for her pretty sister was motherly and protective. She hated Margaret to be left out; she hated her antics to be misunderstood. In her own intuitive fashion I think she saw ahead how later on Margaret was bound to be misrepresented and misunderstood. How often in early days have I heard her cry in real anguish, “Stop her, Mummie. Oh, please stop her,” when Margaret was being more than usually preposterous and amusing and outrageous. Though Lilibet, with the rest of us, laughed at Margaret’s antics – and indeed it was impossible not to – I think they often made her uneasy and filled her with foreboding.’

Of course, prescience benefits greatly from hindsight. By the time she wrote her book, Crawfie knew how the story was developing. Nevertheless, Margaret was only nineteen when The Little Princesses was first published; the dark forest lay ahead.

Across fifteen years, Crawfie chronicles Margaret’s progression. A keen reader, she goes from The Little Red Hen to Black Beauty, and from Doctor Dolittle to The Rose and the Ring. The young Margaret proves an obsessive chronicler of her own dreams. For many of us, this is the hallmark of a bore, but apparently not for Crawfie or Lilibet. ‘She would say, “Crawfie, I must tell you an amazing dream I had last night,” and Lilibet would listen with me, enthralled, as the account of green horses, wild-elephant stampedes, talking cats and other remarkable manifestations went into two or three instalments.’

Margaret used her imagination in more pragmatic ways, too, employing an imaginary friend called Cousin Halifax, ‘of whom she made every use when she wanted to be tiresome. Nothing was Margaret’s fault; Cousin Halifax was entirely to blame for tasks undone and things forgotten. “I was busy with Cousin Halifax,” she would say haughtily, watching me out of the corner of her eye to see if I looked like swallowing that excuse.’

Little Margaret was also ‘a great one for practical jokes’. Like most, hers contained an element of sadism, particularly when perpetrated on those who couldn’t answer back. ‘More than once I have seen an equerry put his hand into his pocket, and find it, to his amazement, full of sticky lime balls … Shoes left outside doors would become inexplicably filled with acorns.’ Later, she was to marry a fellow practical joker, one of whose pranks was to secrete dead fish in women’s beds.

For now, Margaret was developing a talent for mimicry, generally sharpened on her elder sister. Lilibet was, at that time, afflicted with a condition which these days would probably be diagnosed as obsessive-compulsive disorder. In later life she could channel it into waving, cutting ribbons, asking strangers how far they had travelled, and so on and so forth, but in those early years it was more of a problem than a solution. ‘At one time I got quite anxious about Lilibet and her fads,’ wrote Crawfie. ‘She became almost too methodical and tidy. She would hop out of bed several times a night to get her shoes quite straight, her clothes arranged just so.’

Crawfie was convinced that the best cure lay not in sympathy, but mockery. ‘We soon laughed her out of this. I remember one hilarious session we had with Margaret imitating her sister going to bed. It was not the first occasion, or the last, on which Margaret’s gift of caricature came in very handy.’

For all Margaret’s joie de vivre – perhaps because of it – people felt more comfortable with Lilibet than with her little sister. One elderly man in Scotland was devoted to Lilibet, but, says Crawfie, ‘he was frightened of Margaret. Old men often were. She had too witty a tongue and too sharp a way with her, and I think they one and all felt they would probably be the next on her list of caricatures! Poor little Margaret! This misunderstanding of her light-hearted fun and frolics was often to get her into trouble long after schoolroom days were done.’

Her lifelong love of keeping others waiting was already evident in adolescence; so was her easy, almost eager, acceptance of the privilege bestowed upon her at birth. ‘Like all young girls, she went through a phase when she could be extremely tiresome. She would dawdle over her dressing, pleased to know she kept us waiting.’ Crawfie hoped she had cured this shortcoming, but evidently not. On one occasion, ‘at adolescence’s most tiresome stage’, when Margaret was ‘apt at times to be comically regal and overgracious’, Lilibet’s suitor Philip, nine years Margaret’s senior, decided to take her down a peg or two. ‘Philip wasn’t having any. She would dilly-dally outside the lift, keeping everyone waiting, until Philip, losing patience, would give her a good push that settled the question of precedence quite simply.’ Crawfie makes free with the adjectives ‘tiresome’ and ‘regal’, but she only ever applies them to Margaret, never Lilibet. For Lilibet, life was all about doing the right thing. For Margaret it was, and would always be, much more of a performance.

* Late in life, Jessica Mitford admitted that as a young woman she had tried to spread the rumour that both the Queen and Princess Margaret had been born with webbed feet, which was why nobody had ever seen them with their shoes off. Auberon Waugh attempted to play a similar trick with the children of Princess Anne and Captain Mark Phillips, noting in his Private Eye diary that young Peter Phillips had four legs, and ‘the mysterious Baby Susan … is said to have grown a long yellow beak, black feathers and to croak like a raven’.