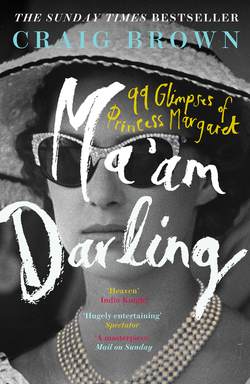

Читать книгу Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret - Craig Brown, Craig Brown - Страница 29

23

ОглавлениеAh! The Group Captain! The rest of us are allowed to forget a youthful passion, but the world defined Princess Margaret by hers, bringing it up at the slightest opportunity. The two of them – the Group Captain and the Princess – had called it a day four years before, when she was twenty-five years old, but when you are royal, nothing is allowed to be forgotten. That is the price to pay for being part of history.

Those who think of Princess Margaret’s life as a tragedy see the Group Captain as its unfortunate hero. He was the dashing air ace, she the fairy-tale Princess, the two of them torn apart by the cold-hearted Establishment. For these people, their broken romance was the source of all her later discontent. But how true is the myth?

Peter Townsend entered the scene in February 1944, when he took up his three-month appointment as the King’s Extra Equerry. At this time he was twenty-nine years old, with a wife and a small son. Princess Margaret was thirteen, and a keen Girl Guide.

The King took to him immediately; some say he came to regard him as a son. Three months turned into three years, at which point Townsend was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order; after a further three years he was promoted to Deputy Master of the Household. Following the death of the King in 1952 he moved to Clarence House, as comptroller to the newly widowed Queen Mother.

When, precisely, did Townsend start taking a shine to the young Princess? For all the fuss surrounding him, it is a question rarely asked. In his autobiography Time and Chance, published in 1978, when he was sixty-four, he fails to set a date on it, insisting that when he first set eyes on the two Princesses, he thought of them purely as ‘two rather adorable and quite unsophisticated girls’.

But by the time of Margaret’s fifteenth birthday in August 1945, he was already thinking of her in more affectionate terms. Describing a typical dinner party at Balmoral shortly after the end of the war, he writes that the gentlemen would join the ladies for ‘crazy games, or canasta, or, most enchanting of all, Princess Margaret singing and playing at the piano’. By now, he was clearly quite smitten:

Her repertoire was varied; she was brilliant as she swung, in her rich, supple voice, into American musical hits, like ‘Buttons and Bows’, ‘I’m as corny as Kansas in August …’ droll when, in a very false falsetto, she bounced between the stool and the keyboard in ‘I’m looking over a four-leaf clover, which I’d overlooked before …’, and lovable when she lisped some lilting old ballad: ‘I gave my love a cherry, it had no stone.’

He accompanied the Royal Family on their 1947 tour of South Africa; by now the Princess was sixteen, and Townsend exactly twice her age. ‘Throughout the daily round of civic ceremonies,’ he recalls, ‘that pretty and highly personable young princess held her own.’ Margaret herself was more open, telling a friend, in later life, ‘We rode together every morning in that wonderful country, in marvellous weather. That’s when I really fell in love with him.’

The tour ended in April 1947. In his autobiography, Townsend insists that he returned home ‘eager to see my wife and family’. But, as it happened, ‘within moments’ he sensed that ‘something had come between Rosemary and me’. He now takes a break in his narrative to detail the difficulties within his marriage.

Townsend had married Rosemary Pawle in 1941. He paints it as a marriage made in the most tremendous haste. ‘I had stepped out of my cockpit, succumbed to the charms of the first pretty girl I met and, within a few weeks married her.’

At this point, Townsend launches into one of the most curious parts of the book, a rambling homily against the perils of sexual attraction. ‘I cannot help feeling that the sex urge is a rather unfair device employed by God,’ it begins. ‘He needs children and counts on us to beget them. But while He has incorporated in our make-up an insatiable capacity for the pleasures which flow from love, He seems to have forgotten to build a monitoring device, to warn us of the unseen snags which may be lurking further on.

‘Sex,’ he continues, ‘is an enemy of the head, an ally of the heart. Boys and girls, madly in love, generally do not act intelligently. The sex-trap is baited and set and the boys and girls go rushing headlong into it. They live on love and kisses, until there are no more left. Then they look desperately for a way of escape.’

One of the anomalies of this passage is that, when Townsend rushed into this particular sex-trap, he was rather more than a boy. In fact, he was a distinguished Battle of Britain fighter pilot of twenty-six, the recipient of the DSO and the DFC and bar.

His marriage, he says, ‘began to founder’ on his return from South Africa. The couple’s problems were ‘intrinsic and personal’, principal among them his yearning to go back to South Africa and ‘Rosemary’s fierce opposition to my ravings about South Africa and my longing for horizons beyond the narrow life at home’. He argues that while ‘Rosemary preferred to remain ensconced in her world of the “system” and its social ramifications’, he was a rebel who reacted instinctively against ‘the conventional existence, the “system”, the Establishment, with its taboos, its shibboleths and its obsession with class status’. At this time the Group Captain was the equerry to the King, and had applied (unsuccessfully) to be a Conservative parliamentary candidate, neither the hallmark of a rebel.

Halfway through 1948, the Princess shed the ‘Rose’ in Margaret Rose. It seems to have been her way of declaring that she was no longer a little girl but a young woman, a transition greeted with a certain lasciviousness by some of her biographers.

‘Never before had there been a Princess like her. Though she had a sophistication and charisma far in advance of her years, she was young, sensual and stunningly beautiful,’ observes Christopher Warwick. ‘With her vivid blue eyes … and lips that were described as both “generous” and “sensitive”, she was acknowledged to be one of the greatest beauties of her generation. In addition, she was curvaceous, extremely proud of her eighteen-inch waist … unpredictable, irrepressible and coquettish.’

Phwoarr! Tim Heald is equally smitten: ‘At eighteen, she was beautiful, sexy … the drop-dead gorgeous personification of everything a princess was supposed to be.’ Furthermore, she was ‘a pocket Venus … an almost impossibly glamorous figure’.

Her emergence into adulthood had its drawbacks. She was burdened with a succession of royal duties, most of them bottom-drawer and dreary. ‘The opening of the pumping station went very well in spite of the gale that was blowing,’ she wrote in a letter that year to her demanding grandmother, Queen Mary. ‘I am afraid that one photographer rather overdid things by taking a picture of me with my eyes shut.’ A little later, she oversaw the official opening of the Sandringham Company Girl Guides’ hut. The speech she delivered reflects the nature of the occasion:

Looking around me, I can imagine how hard Miss Musselwhite and the company must have worked … I do congratulate you on the charming appearance of your new meeting place. I have been in the movement ten years as a Brownie, a Guide and a Sea Ranger … I have now great pleasure in declaring this hut open.

At the same time, her elder sister was opening bridges, launching ships, taking parades and welcoming foreign dignitaries.

From now on, would Margaret have to measure her life in scout huts and pumping stations? Was that all there was? As her day job as her sister’s stand-in grew ever more mundane, who could blame her if she looked for excitement elsewhere?