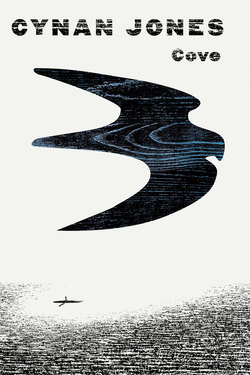

Читать книгу Cove - Cynan Jones - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеYou hear, on the slight breeze, the tunt tunt, tunt tunt before you see the boat. You feel illicit.

When the boat comes alongside they cut the engine. Shout.

Waves break, the breeze. You don’t hear. Swash filters in the pools.

A man in the prow carries a boat hook as if it’s a harpoon. They are in drysuits, white helmets, bright life jackets.

One of the crew seats himself on the gunwale and pushes himself into the water. He swims strangely, held up by the life jacket, lifted and pushed by the water. Like a spaceman.

You are not sure whether the kick comes from the baby or the sureness he has news.

When he comes from the water he stumbles and trips on the stones, clearing his nose of seawater. As if refinding himself.

For some reason he takes off his gloves as he talks.

“Have you been on the beach?” he asks.

You nod. Say, “Yes.” You cannot hide the subtle bell of your stomach now. “I was on the fields for a while but came down. Around the point.”

When he moves the water falls from inside his life jacket. He seems to wait for it.

“There’s a missing child,” he says.

The boat floats behind the man, prey, unpowered, to the shift and swell. You hear the engine crack, rattle off the high shale cliffs. The crew bring the boat around. Then cut the motor again.

The man’s face is reddened, shocked-looking after the water.

You went down to the beach after finding the pigeon.

First the burst of feathers; farther on, the wing, torn off at the shoulder. It had blown across the field like a sail, the sinews and scraps of it dried translucent in the sun.

The rest of the bird was by the stile.

The head was gone, the meat of its chest. The breastbone oddly, industriously clean.

Then you saw the rings. One blue, one red. The red slightly split. The blue one glassy and unnatural on the leg.

You had a strange sense of horror from the pigeon. That it knew before being struck. Of it trying to get home. Of something throwing it off course.

You feel you must return the rings. Let the person it belongs to know.

You pull the leg, try to break the joint. Pull more strongly until the limb rips from the socket. A peregrine, you think. Try to snap the knee with the act of loosening wire.

In the end, you use a stone to crush the leg repeatedly until the rings slip off.

You go onto the beach to clean your hands.

The sand is wet, intimate. There is the faint sugary crunch, the smallest suction under your feet, the wash, the wish of the sea.

Turnstones rise and peep ahead, flashing for a moment before they drop a few yards on. And because you did so as a child, you go to the seaweed strewn at the high-water line and turn it with your feet. Sandhoppers flick chaotically.

The water is cool on your hands, your bending awkward now. With your thumb you rub a toffee of dark blood away and it seems to unfurl in the salt water, thread out in the pool.

A little way off you see something you think is a wetsuit shoe and the world tips, until you realize it’s a sneaker, colorful, like a tiny shelduck.

When you stand, where you held your weight against a rock, the dents of barnacles are in your skin.

The man speaks into his radio, pinches the handset on his chest and speaks. You see the crew receive him, answer, hear the boat motor in the radio, as if you suddenly hear the man’s organs, his heart.

“No. It’s clear,” he says.

The wear of the slow search crosses his eyes. As if, for a split second, it is very early morning.

He puts his gloves back on and nods, steps back into the sea.

As he swims you see them dip the boat hook, pull something from the water. They examine it then throw it back and it bobs like a duck.

They help the man back in. You see him shake his head and point.

Then you watch them as they head out, in a line across the bay.

It’s only when they’ve gone you realize they’ve missed something, there, at the edge of the tide.

When you get to it, it is a doll.