Читать книгу Persian Tales - Volume II - Bakhtiari Tales - Illustrated by Hilda Roberts - D. L. Lorimer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеXXXI

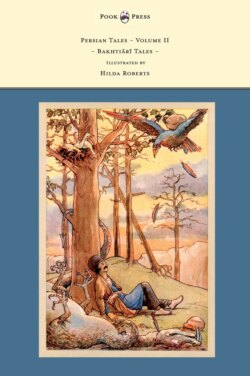

THE STORY OF THE MAGIC BIRD

THERE was once a poor man who made his living by cutting and bringing in thorn-bushes for firewood. Every day he went out and cut a load of thorns, and, putting it on his back, brought it home and sold it; and so he earned his livelihood.

Now he had a very beautiful wife and two sons, one of whom was called Ahmad and the other Mahmad. One particular day he had gone out as usual to the mountain and cut his thorns, but when he sat down with his back to the bundle to take it on his shoulders he found that it was very heavy. Try as he might, he was quite unable to stand up with it. At last he took the sling off his neck and got on to his feet, and then he found that an egg had been placed on the top of his bundle; but it was different from an ordinary hen’s egg. He took it up and put it in his hat, saying: “It may be that God has given me a means of livelihood.”

Then he went home and gave the egg to his wife, saying: “Take this away and sell it.” The wife carried off the egg to the bāzār, and went to a shop and took it out and said: “I have an egg here I want to sell.” The Shopkeeper took it and looked at it, and said: “This is a very superior egg. What will you sell it for?” “I’ll take whatever you like to give me,” replied the woman.—“Is a hundred tumāns a fair price?” “Don’t make a fool of me,” said the woman. —“All right, is two hundred tumāns a fair price?” The woman thought for a minute: “If I say: ‘Give me two hundred tumāns,’ I’ll see whether he is only fooling me or whether he is really in earnest,” so aloud she said: “All right, I’m in a hurry, give me two hundred tumāns.” The man at once brought out the money, counted it, and gave it to her, and she took it up and went home. When she arrived home she said to her husband: “I have sold the egg for two hundred tumāns.” “Well, my dear,” said he, “see you don’t tell any one. This is a special provision that God has made for us.”

Next day he again went out to the mountain and he saw a very beautiful bird come and lay an egg and go away. Again he took the egg home with him, and his wife as before took it to the shop and sold it for two hundred tumāns and went her way.

Now the Shopkeeper came to know that whoever should possess the head of the bird, whatever kind of a bird it might be that laid these eggs, would become ruler of a country, and whoever should possess its liver would find a hundred tumāns under his pillow every night. So the Shopkeeper went and found an old woman, and said to her: “Old woman, I have fallen in love with the wife of old Father Thorn-gatherer. If you will make her friendly to me, I’ll give you whatever you want.” “All I want,” said the old woman, “is as much flour and grape-syrup as I can eat every day.” “Come along here, then,” said he, and he gave her flour and syrup, and she ate her fill.

Then she got up and went to the house of old Father Thorn-gatherer and sat down beside his wife and said: “O my daughter, wouldn’t it be a pity that you should waste your life living with a white-bearded old man like that?” “It’s just my bad luck,” replied the wife. “Ah, my dear,” said the old woman, “but I’ll show you a way out of it if you’ll only listen to me.” “Well, tell me,” said the wife, and she swore that she would do whatever she was told.

Then the old woman said: “I know a young man who is so much in love with you that he is quite ill. I’ll introduce him to you and make him your friend.” “Very well, do so,” said the wife.

Then the old woman came joyfully back to the shop and said: “Now give me as much flour and syrup as I can eat, and I’ll tell you something.” So the Shopkeeper gave her flour and syrup, and she ate till she could eat no more. Then she said: “I have made her quite excited about you, and she has given you an appointment to visit her there to-morrow.”

Next morning they set out together, and no sooner had the Shopkeeper arrived at the Thorn-gatherer’s house than the wife fell so violently in love with him that she almost died, and lost all control of her heart. They sat down together, and amused themselves kissing and talking and playing with each other. Soon, when the Shopkeeper saw that the woman was worse in love with him than ever, he said: “If we are to be friends, there’s a condition that must be satisfied.”—“What is it?” “Well,” said he, “it’s this: you must persuade old Father Thorn-gatherer to catch that bird and bring it home. When he has done so, you must let me know, and I’ll come and tell you what to do.” He sat on for two or three hours longer, then he got up and went back to his shop, and the wife that evening coaxed her husband to promise to try and catch the bird.

Next morning old Father Thorn-gatherer came in and said: “Well, I’m going off now to gather thorns.” “That’s an excellent idea,” said his wife. So he picked up his knife and sling and went off to the mountain. When he got there he cut the thorn bushes and made up his bundle, and sat down to get the bundle on his back. Just as he was getting up, the bird came and lighted on the bundle and was evidently going to lay an egg. Very slowly and quietly the old man put out his hand and caught its two legs. It struggled a great deal, but he held on tight and did not let it go. Then he put the bird under his arm and went off home with it.

Now the old, Thorn-gatherer sent his two sons every day to an ākhund to learn to read. When her husband brought in the bird the wife was greatly delighted, for she said to herself: “Now the Shopkeeper and I will become great friends,” and she went quickly and told him. “Do you know what you must do?” said he.—“No.”—“Well, you must go and kill the bird, and you must cook an āsh and put the bird’s head and liver in it, and let it stand till I come. Then I will do whatever you wish.”

The woman then returned home, and at once cut off the bird’s head, and cleaned it and put it and the liver in the āsh. Then she kept watching for the Shopkeeper, saying: “When will he come, so that I may get my desire?” She saw that he was late, and she could not control her impatience, so she went out to an open space where she could see the road and watch for his coming. While she was still out the children came back from the ākhund’s for dinner, and they saw the pot of āsh standing on the fireplace. They took off the lid and saw that there was a fowl in the pot. They ate some of the āsh, and Ahmad took the head to keep as a talisman and Mahmad took the liver, then they put back what remained on the fireplace. Having had their dinner, they went off again to the ākhund, and each fastened his talisman in an amulet round his neck.

At the time of the mid-day meal the woman returned to the house with her. friend. “Good,” said she, “I’ll bring dinner,” and she went to get the pot off the fire, but saw that it had been tampered with. To herself she said: “There now, do you see, after all the trouble I’ve taken I’ve not secured my object.” However, as there was nothing else to be done, she poured ghee over the dish and brought it and set it before her friend. But when he examined it and found that it contained neither the head nor the liver of the bird, he flew into a passion, and got up, saying: “You bring me only the remains of a dish of which some one else has already eaten.”

“It wasn’t my fault,” said the woman; “the children must have come back from the ākhund’s and eaten a little of it. Now I’ll cook another fowl for you.” “But what I want isn’t here,” replied the man.—“What is that?”—“The bird’s head and its liver.”

Now the boys came up behind the door and they heard their mother talking with a strange man, and she was begging his pardon and saying: “My children ate some of the āsh. I’ll cook another for you,” but the man wouldn’t be appeased. Then the elder brother said: “Brother, this is some companion of our mother’s. Don’t interfere, and let me see what they say.” So they stood still and listened, and the man said: “If you really wish that we should be friends, you and I, then bring your children to the house. I will give them a drug that will make them unconscious, and I will then recover the head and liver of this fowl. After that I will restore the boys to consciousness again.” “On my eyes be it!” said the mother. “I will do exactly as you tell me. Sit down, they will be coming in presently.”

But the elder brother heard all this and said: “Brother, let us fly. If we don’t, they will kill us.” So they fled for their lives. Meanwhile the man sat on waiting, till at last when he saw they weren’t coming he got up and went away. The woman kept watching the road for the boys, but when they hadn’t come by supper-time she realised that they must have been listening and have taken fright and run away. Then she scratched her face and cut off her hair and cried out: “My sons are lost! Do you see what misfortune has fallen on my head? The old woman deceived me. I killed the bird, and my sons have run away for good. I fell in love with a strange man, and I haven’t even got what I wanted!”

Now. old Father Thorn - gatherer came back from wherever he had been to, and saw his wife mourning with her hair cut off and her face all scratched. “Woman,” said he, “whatever has happened to you?” “Ashes on my head!” she replied, “my sons have disappeared!” So the Thorn-cutter fell to weeping too, and from grief for their sons both of them became blind.

Now hear what befell the boys. They travelled along together for several days, and every night there was a hundred tumāns under the pillow of Mahmad, who had the bird’s liver round his neck. At last they came to where the road divided into two, and they saw inscribed on a stone that if any two persons both went along one road they would die, and that one of them must take the left-hand road and one the right. The one who went to the left, after many hardships, would attain his desire, and the one who went to the right would likewise secure his, but more easily. They sat down and threw their arms round each other’s neck and wept. Then said Ahmad: “O Brother, what good will come crying? Let us get up and be off.” So they rose up, and Ahmad held to the right and Mahmad to the left, and they started off on their different ways.

Wherever Mahmad spent the night a hundred tumāns turned up under his pillow. As he approached a certain village a Castle came into view, and as he went along the road he saw a number of people sitting in the midst of dust and ashes. He went up and inquired of them: “Why are you sitting like this?” “Friend,” said they, “we are all sons of a merchant and khān, and we owned great possessions. Now there is a Lady who lives in this Castle, and she takes a hundred tumāns a night to let a man spend the night in it. In this way we have spent every penny we had, and now we haven’t the face to go back to our own country, nor have we anything more to give the woman. So we have no choice but to stay here.”

“This is the very place for me,” thought Mahmad to himself, and he went up to the Castle and said: “I have a hundred tumāns, may I stay for the night?” “By all means,” said they, and he paid the money and stayed. Now the Lady of the Castle had several slave-girls who were like herself; no one could escape from them. One of these slave-girls came and sat down with him, and they kept each other company till morning.

When it was daylight the slave-girl said: “Be off with you,” but he said: “I am going to stay here to-night too.” “Very well,” said she. He stayed for several nights, and the woman said to herself: “Where is he getting all this money from? We saw that he came here without any animals or property, and now he gives us a hundred tumāns every day. I must watch what he does.” One day she watched, and saw that he put his hand under his head and brought out a hundred tumāns and handed it over. Then she understood that he must have the liver of the mountain bird as a talisman, and she came and told her mistress.

Thereupon the Lady of the Castle came and gave him some old wine with a drug in it which threw him into a deep sleep. When he was unconscious she took the amulet from him and hung it round her own neck. Then she beat him on the back of the head and turned him out, and she sent a man with him saying: “Take him and turn him out, and then come back yourself.” The man did so, and Mahmad went his way.

Night overtook him, and he lay down and slept just where he was, and when morning came he found there was no hundred tumāns under his pillow nor anything else, and his amulet was gone. He pursued his way over a wide desert till he came to a flat open space, where he found three men sitting together quarrelling. He went up to them and said: Friends, who are you, and why are you quarrelling?” “We are the sons of Malik Ahmad, merchant of Bīdābād,” said they, “and we have come into our father’s estate, for he himself has died. Now all the estate has been dissipated and only these three articles remain to us, and we cannot agree how to divide them peaceably.” Then they asked: “Who are you?”

“I am the son of the Qāzī of a town,” said he. “Excellent,” replied they. “Now, Qāzī, just apportion these things for us.” “Bring them here, then,” said he. Now he perceived that these men were the sons of the very man who had been his mother’s companion, and from whom he and Ahmad had fled.

They brought the articles, and he saw that they were a bag, a carpet, and an antimony vial. “Very good,” said he, “now what is the particular virtue of each of these?” “The peculiarity of the bag,” said they, “is that if you put your hand into it and pray you will find in it whatsoever you wish for; and if you sit on the carpet and say: ‘O Your Majesty King Sulémān, carry me off,’ it will bear you off to wheresoever you wish; and as for the antimony vial, when you paint the antimony on your eyelids, then wherever you may choose to go no one will be able to see you.”

“Very good,” said Mahmad, “now do you know what you must do?” “No,” said they.

“Well,” said he, “I have a bow and arrow here; I will shoot the arrow and you three will run after it, and whoever first brings it back will be the owner of all three articles. The brothers all agreed to this, saying: “Let them all belong to one; it will be better so.” Mahmad then placed the arrow against the string of his bow and shot it with all his strength, and all three started off at full speed, each jealous of the other, and each thinking: “I must get back first and win all three things.”

But while they ran off after the arrow, Mahmad sat down on the carpet and rose up into the air, saying: “Take me to the Castle of the Lady,” and he sped away through the air. When the three brothers saw him flying off they beat their heads and said: “Now, do you see what we’ve gone and done? We have told the fellow the peculiar properties of the bag, the carpet, and the vial, and now he has gone off and taken them with him!” But from up in the air Mahmad shouted to them: “Don’t beat yourselves! The right man has come to his rights. It was your father who forced my brother and me to flee for our lives.”

Straightway he arrived at the foot of the Castle and hid away the things and went up to the gate. The Lady of the Castle saw him coming and said: “So you’ve come back, have you?” “Yes,” said he, “and I’ve brought something for you. It wasn’t possible to bring it here; we must go and look for it together.” The woman’s greed was awakened, so she got up and went with him, and they took their seats on the carpet. Mahmad prayed: “Take us to the foot of the Haur Tree1 in the middle of the sea.” Immediately they rose up and travelled through the air till they came to the Haur Tree in the middle of the sea; God alone knows how many years’ journey it was distant.

When the Lady of the Castle found herself beneath the tree in the middle of the ocean she said: “This is all very well, but I have nothing with me here.” Mahmad promptly answered: “I’ll marry you. You belong to me now.” “Very good,” said she, and he married her. They remained there some days, and everything they had need of they obtained from the bag.

“Well,” said she, “now that I belong to you, tell me what is the special property of these things.” And Mahmad so lost his common sense that he behaved like a fool and told her all about each of the things. “That’s splendid,” said his wife, but to herself she said: “May my woes descend on your head! I must escape and leave you here until you die.” Presently Mahmad went down a well, and took off his clothes to have a wash. As soon as he had disappeared into the well the woman sat down on the carpet and said: “Take me back to my own Castle!” and up she went into the air.

Mahmad sat down on the carpet and rose up into the air.

Now when Mahmad looked up and saw her, he beat his head and cried out: “Why did I tell her?” “By the soul of your father,” answered his wife, “you will stay where you now are till you die, for you brought me here by craft!” Straightway she arrived at her own Castle, but Mahmad remained behind in great distress and confusion, crying out: “O God, what am I to do? There is no road to get away by, and there is no food here to keep me from dying,” and he wept so much that he fell asleep.

He dozed for a little, and then partly woke up, and found that two pigeons had come and settled on the tree above his head. They said: “Didū, Didū,”1 and then one of them said: “My dearest sister, do you know who this man is?”—“No.” “This is Mahmad,” said the first, and then she went on and told her sister all about him, adding: “And now, do you know how things can be put right for him?”—“No, I don’t.” “Well,” said the first pigeon, “if he will wake up so that I can tell him what to do, and if he will act accordingly, his affairs will come right, but if he goes on sleeping he will just have to stay here till he dies.”

Mahmad heard and said: “Sister, I pray you, in God’s name, tell me what to do!” “Well,” said the pigeon, “do you see this tree?”—“Yes.”—“All right, you must wrap the bark of it round’ your feet, and you will then be able to walk over this sea, just as if you were going over dry land. Take also a twig of the tree, and if you strike any person with it and say: ‘Haush!’2 he will turn into a donkey, and if you strike him with it again and say: ‘Ādam!’3 he will become a man again. Lastly, you should take some of the leaves, and if you draw them over the eyes of a blind man he will recover his sight.”

When the pigeon ceased speaking Mahmad woke up entirely, and the birds flew away, but as they went one of them said: “O man of little patience! I know another thing, but you gave me no chance of telling it to you.”

Then Mahmad went off and tore some bark from the tree and tied it round his feet, and he cut a wand and held it in his hand, and plucked some of the leaves and put them in his pocket. Then he started out over the water and found that he could walk on it just as if it were dry land. He went on and on, and found that he covered a great distance every hour, and he did not stop till he came to the Lady’s Castle. There he saw her sitting over the gate and looking out.

She seemed to be in great good spirits. When she recognised Mahmad she cried: “Hullo, what trick have you played now that you have been able to come over the sea?” “But I mustn’t let him come into the house,” thought she, and she called out to her servants: “Don’t let this son of a dog come into the house!” “Son of a dog yourself!” retorted Mahmad, “I’ve come to burn your father.”

The men about the place ran up to turn him back, but he struck them with his wand and they all turned into donkeys. Then he came up to the woman herself and struck her with the wand and said: “Haush!” and she also turned into a donkey. Then he put saddle-bags on her, and set her to carrying earth till it was night, when he tied her up and threw down some straw in front of her: “Let us see how a person who has lived on flattery and kindness will manage to eat a handful of coarse straw left over by other animals!” But she only hung her head, and tears streamed from her eyes.

“Well, you won’t get off,” said Mahmad, “until you have shown me where the liver is, and have given me back the carpet and the bag and the antimony vial.” But she continued to hang her head, for she had no language in which she could speak. “I’m going to bring you old wine, which you must drink,” said he, and still she hung her head. Then he noticed that there was an amulet round her neck which contained the liver of the bird. So he took the talisman and hung it again round his own neck.

Then he struck her with the wand and said: “Adam!” and she became a woman again just as she was before. “All right now,” said Mahmad; “come and show me where the other things are.” She told him where they were, and then they both swore not to plot against each other in the future, and they settled down to enjoy themselves together.

Now listen to a few words about Ahmad. As he went along the road to the right he came near to an inhabited place. As it chanced, the ruler of the people there had died, and they were flying a hawk to see on whom it would alight, for such was their manner of choosing a new King. But the hawk went and lighted on a wall. “Let this traveller come up,” said the people, “and let us see who he is.” So they made him draw near, and then they flew their hawk again. This time the hawk flew and lighted on Ahmad’s head. But the people were not minded to approve this choice, “for,” said they, “what do we know as to who this fellow is?”

Again they flew their hawk, and again it lighted on Ahmad’s head, but once more they would not accept him. When, however, it settled three times in succession on the stranger’s head, the elders of the place said: “What harm would there be in letting him be king for a time till we see in what manner he rules?” This was agreed to, and so he settled down to rule the country, and they found that he was an excellent king, and all the people were very much pleased with him.

Now King Ahmad began to think of his brother, and he sent out a man to search for him, and at last they got trace of him. Then Mahmad and his wife, when they received Ahmad’s message, packed up their things and came to him, and the two brothers threw their arms round each other’s neck. Presently Mahmad said: “Brother, do send for our Mother and Father and have them brought here if they are still alive.” So the King sent for them.

Now both the father and mother were blind, but blind though they were, the King’s messengers brought them along. As soon as they were presented to him Ahmad said: “O Mother, .what harm did we ever do that you wished to kill us? It would be but a just punishment that you should sit on in your blindness, but because you rocked us in your arms in our babyhood we will make you well.” Thereupon he took out the leaves of the tree and rubbed them on his father’s and mother’s eyes, and their sight was restored.

Then the mother repented of her evil deeds and said: “What a wicked thing this is that I did!” and they all settled down to enjoy themselves for the rest of their lives.

1 “Haur” may mean “island”; in that case the Haur Tree would only be the “Tree in the Island.”

1 “Didū” in the Bakhtiārī language means “sister.”

2 “Haush” probably means “animal.”

3 “Ādam” means “man,” “human being.”