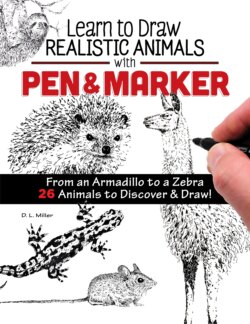

Читать книгу Comfort Pie - D. L. Miller - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPens and Paper

There are two choices you need to make at the beginning of any drawing: what kind of paper and pens will you use? There’s no quick or necessarily right or wrong answer. It mostly comes down to your preferences and goals. Is drawing a pastime you like to do to unwind and escape from your busy day? Or are you looking to eventually sell your artwork and preserve it for generations? Do you just like to doodle and want to sharpen your drawing skills, draw on the go, and keep a small sketchbook by your side? Or do you plan to have a studio with a drawing table, specialized lighting, and a flat file for storing art?

For this book, everything has been drawn with inexpensive pens (under $3 each) and very affordable drawing paper found at your nearest office supply or craft store. This is a good place for beginners to start, and you can build up to more professional and high-quality tools over time if you desire. With that said, following are a few quick tips to help orient you to experimenting with pens and papers.

Pens

There is a vast array of very affordable pens and markers on the market today from many different manufacturers around the world. The only way to truly know what works best for you is to test and experiment.

There are several things to consider when purchasing a pen. As you test new pens, think about each of these aspects to decide whether the pen is right for you and for the drawing you are doing.

Comfort: Is it comfortable in your hand? You don’t want your hand to cramp after only fifteen minutes of use. Even if every other aspect of the pen is great, an uncomfortable pen might not be worth it, because it makes the experience of drawing unpleasant!

Ink flow: Does the ink flow evenly and produce a consistent black line? Some pens produce a more watered-down, grayish line instead of a true black, or skip as you draw, which is frustrating.

Round-tipped pens create consistent, thin lines, whereas chisel-tipped pens create both thin and thick lines.

Bleed: Does the ink bleed, not producing a crisp, clean line? Bleeding can be due to paper not meant for heavy ink use, such as everyday copy paper or school notebook paper. Bleeding can also be due to very thin, most often water-based inks.

Drying speed: How fast does the ink dry? You don’t want to spend twenty minutes working a lot of fur detail into your drawing to then suddenly see small smear lines appear after lightly rubbing your hand over an area. I know from experience that it is very important to test and note the drying time with any new pen before you begin working with it.

Durability: How long does the pen tip hold its shape? Finding tips that stand up to constant stippling and pressure is very important. As you experiment, you’ll begin to see which brands can be used over and over again and which ones lose their edge (literally and figuratively) after only a couple of drawings. Ink life is also a factor of durability: how long does the ink in a pen last?

Tip shape and size: What tip shape does the pen have? The tip shape and thickness of any given pen affects how easy it is to create the texture you’re attempting to draw. There are many animal drawings within this book that require at least three different tips styles, from a fine, hard tip for stippling to a broad-tipped marker for filling in heavy shadows. Keep reading for more detail.

I suggest you purchase a full range of different pen thicknesses and tip shapes for your arsenal so that you’re ready for anything. Pen tip sizes are typically stated in millimeters, which are the sizes given below. Here’s a good set of four pens to start with:

• Fine point, 0.1–0.4mm thickness

• Medium point, 0.5–0.8mm thickness

• Broad point with a chisel tip

• Broad point with a round tip

Avoid brush-tipped pens or pens with very flexible points. The more flexible a tip is, the less control you have when focusing on placing details with accuracy. Brush-tipped pens are generally designed for lettering and are not meant for the level of detail needed when drawing animals in the style covered in this book.

There is a lot of variety in line widths, even in what we call fine-tipped pens.

Paper

As with choosing your pens, selecting the best paper also depends on your goals. Is drawing with pen and marker a fun activity that you like to do to unwind? Or do you want to preserve your work for generations to come? Lightweight or “sketchpad” styles are typically non-archival and are best for practice and on-the-go sketching. (Archival here essentially means long-lasting.) Heavier-weight papers are usually archival and will stand the test of time in terms of discoloring and fading. For pen and marker work, I recommend using a heavier weight paper with a slightly textured surface, or “tooth.”

Many manufacturers develop different kinds of drawing paper for artists. The papers have many different thicknesses and surfaces. As a starting point, there are a few things to avoid:

Avoid glossy or smooth coat finishes. You may be able to draw a very smooth and clean line on these finishes, but inks take much longer to dry. Ink needs to be absorbed by the paper surface and not lay on the surface.

Avoid very thin papers. Papers made for office photocopiers—and your standard printer paper— are too thin. Inks tend to bleed through very quickly and not hold a line. These papers also tend to wrinkle and become wavy on the surface when a large amount of ink is applied.

There are a few critical things to know when shopping for paper at your local craft or art store. Understanding a paper’s weight is important. Thicker or heavier papers can handle more ink (and water and paint) without buckling, curling, or falling apart. Following is a quick list of paper weights and types of paper. Also, note that most art paper manufacturers include a chart on the sketchpad for easy reference.

• 25 lb. (approx. 40 gsm): tracing paper. Do not use for the kind of drawing taught in this book.

• 30–35 lb. (approx. 45–50 gsm): newsprint. Do not use for the kind of drawing taught in this book.

• 50–60 lb. (approx. 75–90 gsm): sketching or practice paper— thick enough to work on with pencils, charcoal, or pastels, but usually too thin for ink or most markers, which may bleed through.

• 70–80 lb. (approx. 100–130 gsm): drawing paper suitable for finished artwork in most media. Paper any lighter than 70 lb. is usually thin enough to see through to drawings or materials underneath.

• 90–110 lb. (approx. 180–260 gsm): heavyweight drawing paper, Bristol, and multimedia papers. Weight in this range is similar to cardstock or light poster board.

• Heavier papers, up to 140 lb. (approx. 300 gsm) or more: most often used for painting rather than drawing. When found in sketchbooks, these are usually rougher papers intended as watercolor journals or to remove for painting on individual sheets.

Another paper aspect to consider is whether the paper is cold press or hot press. Cold press paper, which is the most popular and versatile, has a slight texture. Hot press paper, by contrast, is very smooth and is made by running a freshly formed sheet through heated metal rollers or plates. A good choice for highly detailed illustrations, hot press paper is also used for printmaking, etching, drafting, sketching, and drawing. You can use either type of paper for the drawings in this book.

All of the pen and marker drawings in this book were drawn on a 98 lb. mixed media drawing paper, which is a cold press paper.