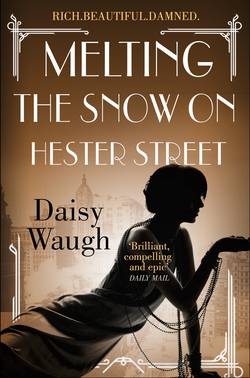

Читать книгу Melting the Snow on Hester Street - Daisy Waugh - Страница 13

7

ОглавлениеNineteen twenty-four, it would have been. Or thereabouts. Almost a year after he joined Silverman. They met for lunch at Musso & Frank – without the marketing guys, because Max insisted on it. He was supposed to be telling her about his first picture since being lured away from Lionsfiel. The film was called The Girl Who Couldn’t Smile, and it went on to gross more for Silverman Pictures than any movie they had yet released. But Blanche had been instructed by her editor not to ‘go too heavy’ on the new movie angle, since readers were unlikely to be terribly interested, and instead to concentrate her questions on the Big Split.

Max’s move from Lionsfiel to Silverman had astonished the Movie Colony because he left behind not only his long-time producer and friend, Butch Menken; but – even more intriguing, at least to Blanche’s readers – his movie-star wife. Until then the three of them – producer, director and star – had made not a single film without each other. They were a winning formula – no one doubted that, and everyone had always assumed the trio was inseparable.

So Max had talked to Miss Blanche Williams about the Split that Rocked Hollywood (as her magazine later entitled the article). And with or without the marketing men to prompt him, he had stuck to the official version of events. Which, with a few vital omissions, wasn’t, after all, entirely divorced from the truth. And Blanche was a good listener – an accomplished interviewer. Over steaming, unwanted bowls of the famous Musso & Frank pasta, and a bottle of Château Margaux, provided by Max and poured by him, under the table, into Musso tea mugs, Max talked with disarming warmth and eloquence about his sadness not to be working with his beloved wife any longer. He and Eleanor had agreed that the moment had come for them both to spread their wings … It was time for Eleanor to experiment with different directors and, for Max, with different actors and actresses. He didn’t mention Butch Menken.

‘What about Butch?’

‘Butch Menken?’ Max waved a dismissive arm. ‘Butch is a good guy.’

‘That’s what I heard.’

‘But creatively, we had taken it as far as we could. Butch is good guy. I have a lot of respect for him.’

‘So there was no fall-out?’

‘There was no fall-out. Whatsoever. Butch and I remain the greatest of pals.’

‘So the rumours …’

He cocked a smile, looked his little interrogator dead in the eye. ‘What rumours would they be?’

She blushed, which didn’t happen often. His gaze was disconcertingly direct. Made her want to wriggle in her chair. He was, she reflected as she recovered herself, without doubt the most attractive man she had ever had lunch with.

‘Well, the rumours that … Heck, Mr Beecham, I’m sure you know what people are saying! That you dumped him. Despite being the oldest and best of friends. Because he just wasn’t up to it … You had creatively outgrown him.’

‘Ahh. Those rumours.’ He smiled. She would never have known it, never have guessed. Under the table, he refilled her mug with red wine, and felt his heart begin to beat again. ‘Butch is a fine producer,’ he said, making a show of picking his words with great care. ‘It goes without saying. Butch is a good producer. But as filmmakers we were travelling different paths. That’s all. We wanted to make different kinds of movies. And consequently we were finding it difficult to agree …’

In any case, Max explained, redirecting the conversation, the offer to join Silverman Pictures was too exciting to turn down. Joel Silverman had promised him more autonomy, bigger budgets, freedom to choose his own scripts. ‘And I have to tell you, Joel Silverman has kept to his word! Ha! And it’s not so often you hear that said, is it? Not in this town!’

‘But why didn’t Mrs Beecham come with you?’ Blanche persisted. ‘She’s such a great actress. Didn’t you want her to come with you? Or was it her? Maybe she didn’t want to come?’

Max shrugged. ‘Of course I wanted her to come. Of course …

‘But you … Maybe you wanted to create some space between the two of you. Is that it?’ Blanche asked, aware that she needed some sort of explanation for the piece, and that he didn’t seem willing to offer one himself. ‘A separation between work and home,’ she said, already writing it down. ‘Yes. I think I can understand that.’

He didn’t know what it meant, and neither – when she thought about it – did Blanche. What ‘space’ between them? The space between them was already immeasurable.

‘That’s right,’ he said vaguely. ‘Creatively.’

She scribbled it down. ‘And tell me,’ she added, still scribbling. ‘Tell me how it happened. Did the two of you sit down and discuss it? Were there tears? Or was it … kind of civilized? Can you tell me a little bit about how it all went down? My readers are longing to know.’

He looked at Blanche, her honest, pretty face so eager to hear whatever he might say next – no matter what. The problem was, he couldn’t remember. Couldn’t remember having the discussion – or even if there had been one. One day it was the three of them working together. And the next day – nothing. He had left them. Both. And he was on his own.

‘Lionsfiel has always been like a family to her,’ he mumbled. ‘That’s what you have to remember. She was never going to leave Lionsfiel. But –’ he added, looking again into those honest eyes, and feeling suddenly, inexplicably compelled to reciprocate, to say something to her that actually had some meaning – ‘I have to tell you,’ he said, surprising himself, not only by its truth but also by the fact of his sharing it with her, ‘I miss her. I miss having her with me on set. I miss spending my days with her. I miss our working together. There was something very, very wonderful about that …’ He paused, thinking about it: the old days. It wasn’t something he allowed himself to do often. And it hadn’t always been wonderful. Of course not. But there had been wonderful moments. Many of them. ‘I’m not sure I realized quite how wonderful,’ he added, ‘until it was gone … Hey. But that’s life, huh?’

‘It sure is,’ she said, scribbling away.

‘Sometimes,’ he added, unwilling to leave the memories just yet, his mind briefly awash with images from good times, the early days – the old nickelodeon on Hester Street, the journey West, the long, slow climb together, ‘when I contemplate a future, making movies without Eleanor … It’s like imagining a world …’ and he paused, searching for the truth – any truth at all – that he might be able to share with her, ‘… it’s like imagining a world without music. Without birdsong …’

‘That’s very, very pretty,’ sighed Blanche. ‘Gosh. I wish someone would say that about me one day.’

He laughed, tilted back in his seat, looked across at her appreciatively. ‘I’ll bet you have guys murmuring stuff like that in your ear just about every day of your life, Miss Williams,’ he said, and he meant it. She was sweet – sweet enough to blush, he noticed. For the second time, too. He watched as she recovered herself; watched as she busily pretended to scribble in her little reporter notebook …

‘But you have to understand, Blanche – may I call you Blanche?’ He leaned across the table toward her. ‘That in spite of everything – really, everything – I had to go to Silverman. Silverman Pictures are making the most exciting – the best – movies in Hollywood right now. I believe that. I truly do believe that. And I make movies, Blanche. I’m a filmmaker. I’m a director. It’s what I do. What I am. There’s nothing else …’

He stopped abruptly, aware that he was revealing too much. He smiled. ‘Any case,’ he continued, ‘I sincerely hope that when you finally get to see the finished cut, you will agree with me that this new picture has been worth the … the pain …’ He paused. Added, more to himself than to Blanche, ‘And of course it has. You know, Blanche, I think, if you don’t mind my saying it, I think it’s my best picture yet.’

And then, somehow, she had looked up from her notebook, gazed back at him with such smitten warmth, that … in the intensity of the moment, the excitement and passion of talking about his beloved project to such a pretty, sympathetic, innocent, intelligent woman, he’d asked Blanche what she was doing later.

And they had spent the rest of that hot August afternoon in Blanche’s bed.

It wasn’t the first time he’d been unfaithful to his wife. Not strictly speaking – not by any stretch. But (if you didn’t count the move to Silverman Pictures), it was the first time Max felt that he was betraying her. Because Blanche was not Eleanor. But she was quite a find. And Max could appreciate that. And he knew from the very beginning that he would be coming back for more.

That was the last time he talked to Blanche about his wife at any length, or in any detail. And it was difficult for Blanche. Always, very difficult. Because Eleanor was a big star. And, if not classically beautiful – her features were irregular; everything was too large, too vital, too wild – there was no question that she shone. Something shone from her on screen – and in life, too. She was a big star. And – yes – Blanche was right. In a city of cheats and shrews, Eleanor’s beauty, her small kindnesses, her beautiful manners, made her a class act. Nobody had a bad word to say about Eleanor.

Max was very fond of Blanche. Blanche knew that. In fact, he loved her. And she knew that, too. But whereas Max Beecham loved Blanche Williams, Blanche Williams was in love with Max.

So it was difficult for her.