Читать книгу Snowden's Box - Dale Maharidge - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1.

Winter Nights

Dale Maharidge

It was a frigid winter, and the Manhattan loft was cold — very cold. Something was wrong with the gas line, and there was no heat. In a corner, surrounding the bed, sheets had been hung from cords to form a de facto tent with a small electric heater running inside. But the oddities didn’t end there: when I talked to the woman who lived in the loft about her work, she made me take the battery out of my cellphone and stash the device in her refrigerator. People who have dated in New York City for any length of time believe that they’ve seen everything — this was something new.

That I was in her loft in the first place was strange enough. A year earlier, I was supposed to get married, but the engagement fell apart. After that, I was in no shape for a relationship and was in any case finishing two books on tight deadlines. I should have been too busy, then, to go to a party in Park Slope, Brooklyn, on a December evening in 2011. The host, Julian Rubinstein, had invited a group of his friends, many of whom were writers, musicians, editors, and documentary filmmakers. His email billed the event as a “fireside gathering,” although when he attempted to get a blaze going in the hearth, the apartment filled with smoke. Through the haze, I noticed a striking woman with dark hair occasionally glancing my way.

“Who’s that?” I asked Julian.

He introduced me to Laura Poitras. I was aware of her 2006 documentary, My Country, My Country, about an Iraqi physician running for office in his nation’s first democratic election. Her current project, she told me, involved filming the massive data center the National Security Agency was building in Utah. Our conversation was intense, and I found myself wondering why somebody as sophisticated as Laura would be interested in me — at heart, I still felt like a blue-collar kid from Cleveland.

Suddenly, she announced it was late. “Want to share a cab?” she asked.

I shambled down two flights of stairs after Laura, and we hailed a taxi. We shook hands when we reached her stop, and I continued north. Two nights later, we met for drinks and exchanged a lot of passionate talk — about our work. When I saw her name in my email inbox the next morning, I clicked eagerly. Maybe she wanted to go out again? She briefly raised that as a possibility, but Laura had something more important in mind. Her message read:

If you want to set up a secure way to communicate (which I think every journalist should) the best method is IM with an OTR encryption. You’ll need: a Jabber account, Pidgin IM client, and OTR plug-in.

Back then, this request — which would now strike many journalists as reasonable, albeit a bit extreme — sounded like gibberish. Why did I need encryption? I’d never done a story that would interest the NSA or any other federal agency. I initially blew off her advice, even as we got involved and began opening up about our projects. Which is how I came to be in that freezing loft, where Laura patiently explained why it made sense for me to put my phone in the fridge. I hadn’t known that a refrigerator could block cellular signals. For that matter, I hadn’t known that even when a cellphone has been switched off, federal agents can still use it to eavesdrop on conversations. Known as a “roving bug,” this tactic dates back to at least 2003, when a judge authorized FBI agents to deploy it against John “Buster” Ardito, a high-ranking member of the Genovese crime family.

Laura’s concerns, I soon realized, were anything but idle paranoia. She had been interrogated by US Customs and Border Patrol agents on more than forty occasions when traveling internationally. The harassment began in 2006, months after My Country, My Country was released. To create that film, Laura had spent eight months working alone in Iraq, chronicling the daily struggles of a doctor who was running a free clinic in Baghdad while also campaigning for a seat in the national assembly. On one particularly violent day, American soldiers spotted Laura filming from a rooftop. Their commander filed a report about her, speculating she’d known in advance about a fatal ambush and showed up to record it. That suggestion was grotesque, not to mention unfounded. Army investigators had “no credible evidence” to support it, a lawsuit revealed years later. Still, the report could have been enough to land her on a terrorist watchlist.

Whatever the government’s suspicions, Laura had no way of knowing — or contesting — them. The experience was maddening. On some occasions agents detained her at the airport for more than three hours. Sometimes they temporarily confiscated and photocopied her notebooks. Once, they took away her computer. On April 6, 2012, after we had known each other for about four months, Laura was grilled at Newark Liberty International Airport. She was coming home from London, where she’d been filming WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and his team for a documentary later titled Risk. As always, following her lawyer’s instructions, she took notes. This time, a federal agent declared her pen was a potential weapon. He threatened to handcuff her if she kept using it. When she offered to write with crayons instead, he said no.

When I heard about what happened, I was on a reporting trip in the Rust Belt, en route home from the Monongahela Valley. I emailed her to commiserate: “Oh man, your re-entry sounds bad.” She wrote back the next morning. By then, she’d recovered her sense of levity. “Oh yeah, it was really fun,” she snarked. “Actually quite humorous, if it weren’t so outrageous.”

I drove through the night, reached Manhattan in the early morning hours, and slept. When I woke up, there was a new email from Laura. She’d pasted into it a message from the journalist Glenn Greenwald, whom she’d contacted about her troubles. He’d written:

You’re a documentarian and journalist and the idea that you are routinely questioned, detained and have your stuff copied every time you re-enter the US is one of the true untold travesties — I will do everything possible to make sure it gets the attention it deserves.

Laura was reluctant to go on the record with Greenwald, even though she’d already reached out to him. She’s an intensely private person. Besides, she didn’t want the whole world to know she’d been filming the WikiLeaks crew. She had to protect her sources. “Do you [see] downsides in going public?” she asked me in an email.

“My instant reaction is yes, go public! Cockroaches are repelled by light,” I wrote back. Hours later, I went to visit her in person and implored her to speak out.

Salon ran an article the next day under the headline “US Filmmaker Repeatedly Detained at Border.” In it, Greenwald wrote:

It’s hard to overstate how oppressive it is for the US government to be able to target journalists, filmmakers and activists and, without a shred of suspicion of wrongdoing, learn the most private and intimate details about them and their work … The ongoing, and escalating, treatment of Laura Poitras is a testament to how severe that abuse is.

At her request, Greenwald didn’t write that Laura had been filming with Julian Assange and the WikiLeaks team. (In all likelihood, government intelligence agencies knew about this, which could explain why the border agents had been so aggressive.) After his story was published, the detentions stopped.

By one measure, Laura and I were a perfect match. We’re both workaholics; we often debated who put in longer hours. I used her as a sounding board for projects, and she did the same with me. In early August, she visited the solar-powered off-the-grid home I’d built in Northern California, overlooking the Pacific. The place is very remote, with the nearest utility lines some three miles away and the closest neighbor a half mile (as the spotted owl flies) across a canyon. We worked through the days and nights. I was finishing a book. Laura was editing The Program, a short documentary about William Binney, the NSA-veteran-turned-whistleblower. After a thirty-two-year career with the agency, Binney had retired in disgust following 9/11. That’s when, as he explained in the film, officials began repurposing ThinThread, a social-graphing program he’d built for use overseas, to spy on ordinary Americans instead.

“This is something the KGB, the Stasi, or the Gestapo would have loved to have had about their populations,” Binney soberly told the camera. “Just because we call ourselves a democracy doesn’t mean we will stay that way. That’s the real danger.”

Though no charges were ever brought against Binney, a dozen rifle-toting FBI agents raided his home in 2007. One pointed a weapon at him as he stood naked in the shower.

After the New York Times published The Program in late August, Laura was ready to start editing her WikiLeaks documentary. This time, extra precautions would be necessary to protect her source material. Her detentions by border officials were still fresh in her mind, and the US government had opened a secret grand jury investigation into WikiLeaks two years earlier. So Laura relocated to Berlin.

Meanwhile, she was contracting out a major renovation of her New York loft. Having been a professional chef in the Bay Area before she made her first film, Flag Wars, she was especially eager to have a working kitchen. Because I’d built and remodeled homes, she asked me for advice. I offered suggestions on such things as countertop materials (she chose concrete).

We remained connected, albeit with an ocean between us. Distance is hard on any two people who are involved. But ours was far from what most people typically consider a relationship. We were both under substantial stress with our work. That October, she came home after winning a MacArthur Fellowship. Her flat was still without heat, and it had a leaking bathroom pipe, which I tried (but failed) to fix. Then she flew back to Berlin.

I wouldn’t see her for the rest of the year. But anytime I emailed, no matter the hour in Berlin — even at three or four in the morning — she answered promptly. This insomnia was chronicled in a journal she’d been keeping, which was later excerpted in Astro Noise: A Survival Guide for Living under Total Surveillance, published by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

On December 15, 2012, Laura wrote: “If only I could sleep I’d be happy in Berlin.”

A month later, she noted in the journal: “Just received email from a potential source in the intelligence community. Is it a trap, is he crazy, or is this something real?”

Little more than a week after making that entry, Laura returned to the United States to shoot footage of the NSA’s Utah Data Center, which was still under construction. According to the journalist James Bamford, the facility, which would begin operations two years later, had been designed as a repository for

all forms of communication, including the complete contents of private emails, cellphone calls, and internet searches, as well as all types of personal data trails—parking receipts, travel itineraries, bookstore purchases, and other digital “pocket litter.”

With these matters on her mind, Laura flew back to New York, where she told me how she’d been approached by a mysterious source who was eager to communicate with her. “Could it be a setup?” she asked. It could. Yet she chose to keep the channel open. We adopted a code for talking about the issue, pretending to discuss the ongoing renovation of her loft. On the last day of January, I invited Laura to dinner at my place. “I had a really good meeting with the contractor today,” she wrote in an email that afternoon. “I look forward to updating you and getting your advice/feedback.”

We talked about the source over dinner. Laura told me that this person wanted a physical address to use in case, as the source put it, “something happens to you or me.” We speculated that perhaps the source wanted to send her a parcel. Hard copy? Data? It was unclear. Needless to say, the material couldn’t go directly to Laura: her mail was surely being scrutinized. Nor could I receive it, because of our connection. She said we needed a third party, someone who wouldn’t be on the NSA’s radar.

“Do you know someone, a journalist, whom you absolutely trust?” she said. “Someone who won’t ask any questions?”

“Sure,” I responded. I immediately thought of the perfect person: my best friend, an author and accomplished journalist who also taught at Columbia. She had just moved, though. While I’d already visited her new place in Brooklyn and knew what the building looked like, I didn’t remember the exact address. I told Laura I would supply the location soon. Later, I mulled my options for getting the street number — what if, on account of my relationship with Laura, my phone or computer had been compromised? I didn’t want to call my friend and ask her, on the off-chance that I’d been tapped, or pull up the address using an online search, in case there was malware on my laptop that could log my keystrokes. Instead, I went to Google Street View and dropped a tiny avatar on a busy road around the corner from where she lived, walked it to her building, and zoomed in on the number posted above her front door.

The next time Laura and I met, I gave her the Brooklyn address. I didn’t confess how I’d gotten it, hoping my workaround hadn’t somehow weakened our security. Since Laura was going back to Berlin and I wasn’t yet using encryption, we spent some time refining our code to use on the phone and in emails. As we stood near my front door — she was on her way to the airport — I scrawled the following notes on a sheet of paper. (For what it’s worth, the published excerpts from Laura’s journal show that she transcribed the code a bit differently. Ours was not a system with exacting precision.)

— Architect = The unnamed source

— Architectural materials = The shipment

— First sink = The primary friend who would receive the architectural materials

— Other sink = A backup friend in California, in case the first couldn’t do it

— Several countertops = Multiple packages

— The carpenter quit the job = Start over with a new plan

— The co-op board = The NSA or FBI (a tribute to the truculent nature of such boards in New York City)

— The co-op board is giving us a hard time = The NSA/FBI is on to us. Trouble!

— Renovation is taking longer than expected = No word from the source

Hours later, Laura emailed from the airport: “Thanks for checking in on the renovation work while I’m away. Hopefully it will be drama free, but that might be wishful thinking.”

Meanwhile, Laura been corresponding with the source, trying to determine why this mysterious figure had reached out to her in particular. In an encrypted message that January, the person wrote:

You asked why I picked you. I didn’t. You did. Your pursuit of a dangerous truth drew the eyes of an apparatus that will never leave you. Your experience as a target of coercive intimidation should have very quickly cowed you into compliance, but that you have continued your work gives hope that your special lesson in authoritarianism did not take; that contacting you is worth the risk.

Laura arrived safely in Berlin, but her worries continued. What if the source was some kind of crackpot — or, worse yet, an undercover agent using her to target Assange? WikiLeaks had already been named an enemy of the state by a 2008 US Army secret report, which also suggested a strategy to damage the organization’s reputation by tricking it into publishing fake documents. (Ironically, that report was later leaked to — and published by — none other than WikiLeaks.)

Laura’s source tried to reassure her he was legit, writing:

[Regarding] entrapment or insanity, I can address the first by making it clear I will ask nothing of you other than to review what I provide …

Were I mad, it would not matter — you will have verification of my bona fides when you … request comment from officials. As soon as it is clear to them that you have detailed knowledge of these topics, the reaction should provide all the proof you require.

Laura had also been wondering: What if the emails from the mysterious person suddenly stopped coming? Was there a backup plan? The source addressed that too, explaining:

The only reasons we will lose contact are my death or confinement, and I am putting contingencies for that in place.

I appreciate your caution and concern, but I already know how this will end for me and I accept the risk. I seek only enough room to operate until I can deliver to you the actual documents … If I have luck and you are careful for the duration of our period of operations, you will have everything you need. I ask only that you ensure this information makes it home to the American public.

Still, Laura felt anxious. On February 9, she wrote in her journal, “I still wonder if they are trying to entrap me … My work might get shut down by the government.”

Soon after making this entry, she gave me the go-ahead to ask my friend about receiving the package. I wrote back on February 12: “That first sink is definitely the cool one. You always want to go with stainless steel. I hate porcelain.”

A week later, Laura emailed: “Thanks for feedback re the sink … The architect will be sending me links to view things as we move forward. I’ll let you know as things progress and timing for doing a site visit. The co-op has been quiet. I hope it stays that way.”

There was occasional confusion as to whether we were discussing her mystery source or the actual renovation, which was still going on. In a few instances, I had to remind myself: sometimes a countertop is just a countertop.

On March 15, Laura emailed, “Things are moving along with the renovation. Still in the preliminary stages. I hope things escalate soon.” She was, in this case, definitely talking about her source.

Before long, the source followed up with Laura, sending her a pep talk of sorts. It read:

By understanding the mechanisms through which our privacy is violated, we can win here. We can guarantee for all people equal protection against unreasonable search through universal laws, but only if the technical community is willing to face the threat and commit to implementing over-engineered solutions. In the end, we must enforce a principle whereby the only way the powerful may enjoy privacy is when it is the same kind shared by the ordinary: one enforced by the laws of nature, rather than the policies of man.

I went back home to California for a few weeks, returning to New York on May 4. Still, nothing had come. Six days later, Laura wrote, “Quick update: My architect is sending some materials. Let me know when you get them.”

I responded: “Will they arrive in the next day or two? My friend who is interested in those plans because of her own remodel is out of town.”

My friend in Brooklyn had decamped to Los Angeles to report a magazine story. A few more email exchanges followed.

“I will know more when that friend gets home and settles in,” I wrote to Laura. “I can’t wait to hear about the design … hope it includes a window for lots of light!”

She replied: “I really hope he figured out a way around the co-op rules to do a window. Keep me posted — I’m really eager to see. If they are ready I’d like to get them so I can start reviewing Thursday. See you soon.”

To which I responded: “Yes, windows are good. We can never have too many in our lives.”

Jessica Bruder

Over the course of a decade and a half of friendship, Dale and I have shared all sorts of experiences. We’ve accidentally driven over a cow after midnight on the high plains of Colorado. We’ve cleared overgrown wilderness trails with chainsaws. We’ve extracted a rancher pinned against a tree by his own truck, and pruned branches from a thirty-year-old Douglas fir on Dale’s California property using a shotgun. (They had been blocking his ocean view.)

Dale and I often jokingly refer to ourselves as a platonic married couple. I was confident that there was nothing he couldn’t tell me. I was wrong.

In February 2013, I was hanging out at his apartment near the Columbia Journalism School, preparing to teach a class. Dale made a sudden request: could we put our cellphones in the refrigerator? At the time, that sounded nonsensical to me — like stashing our shoes in the broiler or our wallets in the microwave. We’d done stranger things, though. “Okay,” I said.

His next question: would I be willing to receive a package in the mail for one of his friends? He didn’t say whom the delivery was for or what it would contain. He just blurted something vague about “investigative journalism,” following up quickly with “it could be nothing.” I wouldn’t be able to ask any questions, he added. Could I handle that?

“Sure,” I said. “No problem.”

The package, he continued, would be labeled “architectural materials.” I should not open it. And we would never, ever speak about it over the phone — or even with our phones sitting nearby. Any mention of the shipment had to be in code.

“We’ll call it the ‘elk antlers,’” Dale said soberly. This was a reference to my dog Max’s favorite chew treats. Elk shed their antlers each year, and apparently there’s a small profit to be made by sawing the racks into bits and selling them to urban pet owners like me. Such deliveries arrived at my apartment regularly by mail.

I tried to keep a straight face. “So when it comes, I’ll tell you, ‘I’ve got the elk antlers.’ ”

“Exactly.”

This sounds like a bad spy movie, I thought. But how do you tell that to someone you ran over a cow with? I agreed to help — even though Dale sounded paranoid to me — because that’s what friends do. Frankly, it never even crossed my mind to turn him down. We retrieved our phones from the fridge. The day went back to normal.

For more than three months after that conversation, nothing happened. Before long I had forgotten about the whole thing, busy with my own writing and teaching.

Then, on May 14, I returned home to Brooklyn after spending a few days in Los Angeles for work. I climbed the stairs to the fourth-floor landing. In front of my door was a box.

That was weird. No one ever bothered to walk all the way up to the fourth floor. Packages usually arrived in a haphazard scatter in the foyer. Sometimes they didn’t stick around for long. In recent months, quite a few boxes had disappeared in a spate of thefts. Their contents included vitamins, an LED tent lantern, a pair of earbuds, the book To Save Everything, Click Here by Evgeny Morozov, and a packet of Magic Grow sponge-capsule safari animals. That last item was to entertain my journalism students. In class we discussed the serendipitous nature of reporting — how small leads grow unpredictably into larger stories — and I mentioned the little gelatin caplets I’d played with as child, dropping them in water and marveling as their contents expanded to reveal the shapes of wild creatures.

Those items weren’t the only things to go missing. Around the same time, my bicycle also got stolen. Someone nicked it from the boiler room in our basement. When I mentioned that to a neighbor, he told me several of his bikes had been taken too.

So it seemed remarkable that the thieves had turned up their noses at this new package. I knelt down to grab it. The words “architect mats encl’d” were scrawled in block letters on the front of the box. How long has this been sitting here? I wondered. After letting myself into the apartment, I took a closer look. Nothing about the package appeared unusual at first. It had been postmarked May 10 in Kunia, Hawaii, and sent via USPS Priority Mail. I shook the box gently, like a child guessing at the contents of a gift. Something inside made a clunking noise. Otherwise it gave up no secrets.

Then I noticed the return address:

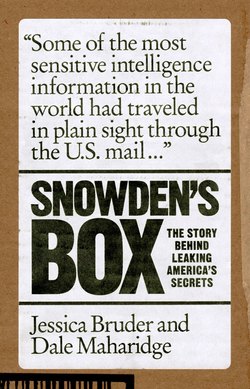

What the fuck? I thought. Is this a joke? There was no way this package had come from the Army intelligence specialist turned whistleblower who’d used WikiLeaks to disseminate more than 250,000 classified diplomatic cables. At the time, Chelsea (then Bradley) Manning had languished for more than three years in military prison, awaiting a court-martial for the biggest security breach in American history.

Meanwhile, it was an unsettling moment to receive a mystery box from someone who might fancy himself a latterday Manning. The Obama administration was zealously pursuing reporters who received classified information. The day before, news broke that the US Department of Justice had secretly seized records for more than twenty phone lines used by Associated Press journalists during a leak investigation. AP president and CEO Gary Pruitt wrote a protest letter to Attorney General Eric Holder, calling the move a “massive and unprecedented intrusion” into the news-gathering process.

Days later, the Washington Post revealed federal investigators had also seized personal email and phone records for Fox News Washington correspondent James Rosen, in connection with another leak probe. In one affidavit, an FBI agent referred to the journalist as “an aider, abettor and/or co-conspirator” — words that still give me the chills.

I called Dale to let him know the elk antlers had arrived, then tucked the box into a messenger bag and headed into Manhattan. When I arrived at Dale’s apartment, I thrust the box into his hand.

“Check this out!” I gestured at the return address. “Your friend sure has a puckish sense of humor.”

Dale looked it over. He was perplexed. I wondered what he knew — and what he didn’t — about the package, but I’d promised not to ask questions. We let the matter rest and went out to dinner.