Читать книгу Some Sunny Day - Dame Vera Lynn - Страница 9

CHAPTER TWO One-&-six for an Encore

ОглавлениеPeople find it hard to believe that I started singing regularly in the clubs when I was seven, but there’s nothing strange about it at all, really. With the club life practically in my blood, with a tradition of party singing deeply ingrained in the whole family, and with my own voice already—so I’ve been told—distinctive in some uncanny way, finding myself singing songs to a real audience, with just a piano for accompaniment, felt almost as natural and inevitable as growing up. I look very serious and grown-up in the photographs from the time, dressed in silk and satin dresses with ruffles which my mother designed and made herself. In one—I must be about seven—I am dressed as a fairy wearing a dress with a sequinned bodice and have a huge net skirt!

The costumes, along with everything else in my early career, were largely down to my mother’s influence: she wanted me to perform. I have to say now that I didn’t particularly enjoy singing. The idea came from the family—it certainly didn’t come from me. For me it was a case of ‘Don’t put your daughter on the stage, Mrs Worthington’. But I had no choice. It was my mother who saw that I started doing formal concerts. And, to my amazement, I got paid for it, although obviously I didn’t see the money myself.

It didn’t happen entirely automatically, of course; somebody had to provide the first push. That came from a man named Pat Barry, who was a male ‘soubrette’ on the working men’s club circuit. ‘Soubrette’ is an odd kind of word, but it used to be bandied about in the business. Originally it meant a girl who sang and danced. By the time the concert parties and then the revues had come along, the word had taken on the meaning of a young female member of the cast who could sing and dance and act, and was therefore useful in several ways. Pat Barry’s talents were singing and tap dancing and clog dancing. A sort of jack-of-all-trades for the stage, then.

Pat knew the family, he’d heard me sing at parties and he thought that I was good enough to appear as an act; and he not only persuaded my mother and father that I ought to go on, but—being an all-rounder himself and keen on the idea of having at least a second accomplishment to call on—he told me I ought to learn to step dance as well. So once a week round at his house he’d teach me to dance on a proper little slatted step-dancing mat on the kitchen floor—a roll-up mat of wooden slats on straps that your shoes would ‘clack’ against. I was tall and leggy as a child and, although that first big illness seemed to have left me unable to run far without getting out of breath, I was acrobatic and nimble enough, and did pretty well. But for me, singing—with all the appropriate actions—was to be the main thing, and the club would bill me as a ‘descriptive child vocalist’.

The clubs themselves were part of a network of entertainment of which, unless you grew up in it, you could be completely unaware. There have been working men’s clubs in practically every industrial and thickly populated working-class area since the end of the nineteenth century, and the East London clubs I started in were just a few out of literally hundreds of such places. The old Mildmay Club at Newington Green was one of the best known.

I appeared many times at the Mildmay, with its large hall where the rows of chairs had ledges on the backs of them to hold glasses of beer, and where the chairman and committee of the club sat in front of the stage at a long table. That was the standard practice and, very much as in an old-fashioned music hall, the chairman could quickly gauge the mood of an audience. This was very important, because it was the committee who decided, according to the strength of the applause, whether you were worth an encore or not. That made all the difference to the money you earned: an extra encore earned you a shilling and sixpence. An encore also meant you were well in, and if it happened in a club you were new to, you could be sure that the entertainments secretary would have taken note of how you went down and would book you again.

In the working men’s clubs the entertainments secretaries were roughly the equivalent of agents, and like agents they were always visiting other clubs, on the look-out for new acts. They were unpaid, but every so often the club would run a benefit night for its entertainments secretary. These were known as ‘nanty’ jobs (the word comes from niente, Italian for ‘nothing’), because the performers offered their services free. Artists would try hard to appear on these shows, for apart from anything else, they were the accepted way of getting into a new club. If you could do a nanty job for an entertainments secretary who didn’t know your act, then it worked like an audition. If he liked you, you’d go down in his book of contacts and you could expect him to remember you later for a paid performance.

Some artists remained more or less permanent fixtures on the club circuit; others used the clubs as a way into ‘the business’ and a step towards bigger things. The comedy team of Bennett and Williams began in the clubs as a double act known, if I remember rightly, as Prop and Cop; the comedian and actor Max Wall started in the clubs too. The Beverley Sisters’ parents were a club act called The Corams. These were names and faces from the bills I used to appear on as a child.

For my first appearance, when Pat Barry got an entertainments secretary to put me on, I learned three songs and had a new dress made: white lace with little mauve bows—I can see it now. You didn’t have ‘dresses’ in those days; you had one dress and that was it. (When that one got shabby, if you were lucky you got another one.) I had a pair of silver pumps, a tiny briefcase from Woolworth’s for sixpence and my rolled-up music, and off I went. Later I would suffer from nerves, like everybody else, but at seven I was simply too young to feel anxious. The thing that excited me was the medal I’d been promised for going on. Our next-door neighbour in Ladysmith Avenue was Charlie Paynter, the trainer/manager of West Ham United football team, and he had said he’d give me a West Ham United medallion if I sang in public. He kept his promise, and I was thrilled, because he was a very important man in our locality. My parents would have been with me that first time too, but I don’t remember them telling me that I’d done well or anything like that. I just remember not wanting to do it but knowing that I had to. The applause made me feel good, though, and I got an encore—and got paid for that.

I don’t remember what I sang on that first occasion, but I know that from my earliest days I seemed to be attracted naturally to the straightforward sentimental ballad. In spite of—or maybe, come to think of it, because of—the happy times I had with my dad, I practically cornered the market in ‘daddy’ numbers: ‘Dream Daddy’; ‘I’ve Got a Real Daddy Now’; and a genuine 22-carat tear-jerker called ‘What is a Mammy, Daddy?’ I sang that at a competition once:

What is a mammy, daddy?

Everyone’s got one but me,

Is she the lady what lives next door

Who cooks our dinner and sweeps up the floor?

I’ve got no mammy to put me to bed

And tell me to go out to play.

Daddy I’ll be such a very good girl,

If you’ll bring me a mammy some day.

Everybody was in tears, and there was tremendous applause, but I didn’t win. When the results were announced, the audience kept shouting out, ‘What about the little girl in the red dress?’ and, in the end, I got a consolation prize. This particular competition took place not far from home in Poplar, East London, and it was one of a whole series run at various cinemas in London by Nat Travers, a local cockney comedian. Afterwards he came round to me and my mum and said, ‘Sorry about that, ducks, but come to Tottenham Court Road next week. I’ve got another competition on there and you’ll be all right.’ But my mother was furious and wouldn’t let me go in for any more of his contests.

Remembering a song, once I’ve learned it, has never been a problem for me, and I could still probably sing you an hour and a half’s worth straight off without repeating myself. I’ve always been able to decide quickly how to sing a song—how to phrase it, what to emphasize. But I had enormous difficulty in learning the words in the first place. I would sit on the floor at home for hours on end, going over them again and again, while my mother doggedly picked out the tune on the piano. Often there’d be tears, and even when I’d finally managed to get a song into my head and came to sing it in public for the first time I’d be petrified in case I forgot the words. Ever so many times I wished I could give the whole thing up, just for this one reason.

Finding material was comparatively easy. The writing and publishing and selling of popular songs was a business then just as it is now, but it was a different kind of business. Live public performances were what counted, not the plugging of records, and anybody who was known to appear regularly in front of an audience could count on being welcome at the various music publishers’ offices, which were then nearly all in Denmark Street, just off Charing Cross Road, the British ‘Tin Pan Alley’. This was where all the music publishers were based, and if they knew you could put a song over, they were often willing to give you copies. So, from quite an early age, I was a familiar little figure up there—something which was to stand me in good stead later when I started broadcasting.

That ‘descriptive child vocalist’ billing was no mere gimmick. Even when I was very small I had an unusual voice, loud, penetrating, and rather low in pitch for my age; most songs had to be transposed from their original key into something more suitable. When I became better known, the publishers would usually do that themselves, but at first I always had to go to someone outside. We found a Mr Winterbottom, who would do you a ‘right-hand part’ for sixpence a copy; if you wanted a left-hand as well it came to one-and-six, but we just used to have the top line done because most of the club pianists were so experienced at this kind of work—which was more than a cut above the ‘you-whistle-it-and-I’ll-follow-you’ school—that was all they needed.

You’d merely hand your music over and they would improvise a bass part on the spot. One or two were actually publishers’ pianists by day—the men whose job was to demonstrate songs to prospective professional customers. (All that has gone now, but forty and fifty years ago that was the accepted way of selling a performer a new number, and those pianists could transpose anything into any key, at sight.) Every now and again you would come across a club pianist who wasn’t much good, but they must have been in a minority, because I can’t recall any great musical disasters.

One minor catastrophe was not the pianist’s fault but mine. Without being a typical ‘stage mother’, my mum always took a very close interest in every aspect of my singing, and my programme for any given appearance was usually the result of a kind of joint decision. We didn’t disagree often, but there was one night when I very much wanted to do one song, and she thought I ought to do another. I must have been a stubborn child, for in the end I won, and it was decided I would sing the one I wanted. I gave the pianist the music for it, but the moment he’d rattled through an introduction (and I must say club pianists’ introductions could sound pretty much alike), I immediately began singing the other one. For a few disorganized bars the two numbers tangled with each other; we both stopped and started, like two people trying to pass one another but always ending up in each other’s way. We did the only thing we could do, and began again from the top. Audiences don’t dislike this sort of thing as much as some artists believe; as long as it doesn’t happen too often, there’s something strangely reassuring about seeing somebody else make a mistake.

That much I accept, and could accept even then. What I couldn’t take were the efforts of some well-meaning entertainments secretaries who would see my deadpan little face and urge me to ‘Smile, dear—smile’. I’d come back at them with, ‘I’m not going to smile; I’m singing a sad song’—and I usually was—‘so why should I have to grin all over my face?’

I was aware that I did not have much choice but to go on stage. Money was short in those days, so any money I could earn helped to swell the household coffers. I hardly ever wanted to be at these concerts, though, and later I was always nervous before I went on. Nobody asked me if I wanted to sing or not. You didn’t argue in those days; you did as you were told. That makes me laugh now, when I think of how youngsters are today. It never entered my mind to be angry with my mother, but there were times when I wasn’t happy. I don’t ever remember saying the words, ‘I don’t want to do it and I’m not going to,’ which is what kids of today might do. This went on until I was about fifteen or sixteen—it wasn’t until I started singing with bands that I started to enjoy it more.

I did club work for something like eight years, mostly in east and north London and on the Essex fringe, but also over the river in places like Woolwich and Plumstead, which were comparatively easy to get to because of the Blackwall tunnel. Coming back from Woolwich one night we missed a bus and had to walk all the way through the tunnel, which had only a tiny pavement and wasn’t really designed for pedestrians, to pick up the tram at Poplar. And there were many other nights when I would wait at Poplar in the cold and wet, and being so tired that I’d fall asleep on the bus long before we got home. While I was still small enough, my dad would sometimes give me a piggyback home late at night, and it was wonderful to stop on the way for fish and chips and what we used to call wally-wallies, which were big dill pickles. Occasionally on the way to a club, when the shops were still open, we’d call in at the little grocer’s near the end of the road for a penn’orth of broken biscuits. These were a great bargain because biscuits came in big square tins in those days and were bought loose— any that got broken were sold off cheap, even the most expensive ones.

Nowadays if child performers earn any money the parents are able to build up the child’s bank account and put money aside for their future. But in my day they were only too glad of the money to keep the house going. Although my father had a job, when I started earning money that helped pay the food bills. In fact the money I earned more than fed me. If I had concerts on the weekend and a cabaret somewhere I could earn seven shillings and sixpence. Unless I did two places in one night, which I did regularly: then I could earn more. And if the public wanted an encore, then the men sitting around the committee table in the club would put money in a kitty—up to one shilling and six. That was useful because it paid for our fares, either on a sixpenny tram or on a shilling-all-night tram. In those days my dad was probably earning about three pounds fifty a week. So there were some weekends when I could almost make in two nights what my father made in a week.

I was not allowed to spend any of the money I earned myself. I didn’t feel good or bad about it; I didn’t think about it. I just did the concerts, knowing that whatever money I earned, it would go into the household. In my younger days going to school I would be given a penny to buy a chocolate cupcake from the bakery opposite the school, and I would have that in my break. It was a little spongey cake with chocolate melted on top, which used to go all hard and crispy—it was so nice. As long as I had my penny for the school break, I never thought to ask for anything more than that. I knew that the money made a big difference to the family as it was a lot of money in those days. You don’t analyse these things when you’re young, but we were always well fed, although not by today’s standards, maybe. The children of today just help themselves to whatever they want. You weren’t allowed to help yourself back then—we would have eaten at mealtimes but rarely between. The only time we had a bowl of oranges on the side was at Christmas. The rest of the year fruit was kept in the larder. I didn’t consider our family poor, though: we were just middle of the road. We never really went short of anything.

I was certainly never hungry. My mother was a plain cook but a good cook. Most women were in those days. There wasn’t all the fancy cooking that we do today. It was basic. We had a roast every Sunday—Mother used to make very good Yorkshire pudding—and then the cold meat on the Monday. And we always had two different sorts of potatoes: roast and boiled. I was thinking about that the other day when I was peeling potatoes: that at home on Sundays there was always a choice. They don’t do that nowadays, do they? You get either boiled or roast, but not both. Funny how things change.

All this time, of course, I was at school, and although the work I did in the clubs was mostly at weekends, the two things still managed to clash—sometimes in unexpected ways. At my junior school in Central Park Road I once asked if I could borrow a copy of the sheet music of ‘Your Land and My Land’, and when I told the teacher what I wanted it for she said, ‘Oh, you sing, do you?’ Obviously she remembered, because one morning at assembly not long after that I was suddenly called on to sing this song. I was petrified, and I had every reason to be, for as I’ve mentioned, my voice was of a rather unorthodox pitch for a little girl, so when the school played it from the original song copy, it was in completely the wrong key for me. It was a terrible mess, and although it wasn’t my fault I was crimson with shame. They must have thought, Good God! How can this child go on stage and sing!

As a matter of fact everything we sang at school was pitched too high for me. Most of the time I couldn’t get up there, and the only alternative was to go into a kind of falsetto voice, which was disastrous. The school disliked my singing voice so much that ironically I was only allowed in the front row of the choir because I opened my mouth nice and wide and it looked good.

If I was ever tired at school it was automatically put down to my going out singing late at night ‘in those terrible places’. My voice and the sort of singing I was doing were much looked down on. One teacher in particular was most unsympathetic. One day she wouldn’t let me go home early in time to get to a competition at East Ham Granada, so when we did come out of school I had to run all the way home, where my mother was waiting with my things—this was the time I sang with my doll—and then we both ran all the way there. I wasn’t much of a runner, and I arrived out of breath, just as the last competitor was coming off. I flew on, somehow struggled through my number—‘A Glad Rag Doll’—and won first prize. Ten bob, it was, and it bought me and my mum enough of that red ripply material that everybody used for dressing gowns in those days to make us a dressing gown each.

I was never keen on school—probably because I wasn’t good at any of the academic subjects. I could never spell; I couldn’t add up; I couldn’t assimilate the facts in history and geography. I never tried very hard at French; I didn’t need French, I was going to be a singer—I can actually remember thinking that. How foolish can you be? I’ve bitterly regretted my poor record at that kind of subject ever since, and it’s left me with a permanent sense of inferiority in certain kinds of company. As if in compensation, I was always good at anything with my hands—drawing, painting and sewing. Gardening too, even then; when we made a crazy paving path at my secondary school, Brampton Road School, I took charge of laying out the pieces. Maybe it’s still there. Cookery was something else I was good at, and botany, though my marks in that came mostly from my little sketches. I wasn’t a great reader, but I read quite well out loud in class—I suppose there was some kinship there with projecting a song. I tended to be good at what came easily to me, and made heavy weather of everything else, like learning songs. But I just wasn’t academic. In fact I never learned to read music, not even to this day.

The whole act of going to school was rather like learning new words, as a matter of fact, because no matter how much I may have disliked it, I never tried to get out of it; I knew it had to be done. I suffered a great deal from bilious attacks as a child, but even if I’d been up nearly all night and felt like death the next morning, when my mother would ask me if I wanted to stay at home, I’d have to explain that I had to go—I musn’t miss school. It turned out in later life that one of the things that was causing the biliousness, and the being ill after eating, say, strawberries, was a troublesome appendix, which would eventually catch up with me right on the stage of the Palladium during the Blitz. But at the time I was just another of those bilious children, with maybe that difference—that instead of using the weakness as an excuse for taking it easy, I felt I had actively to fight it. If I’m not doing what I’m supposed to be doing, I feel I’m slacking. I’ve got to deserve a rest; I feel each day that I’ve got to earn my day. My mother was the same, never still. She didn’t slow down until the mid-1970s, when infirmity forced her to (she died not many years after that), and my recollection of her during my childhood is that she was always rushing about. She wanted to get a lot done, and I suppose I do, too.

We shared that practical streak. As mentioned already, my mother had been a dressmaker before I was born, and not only made all my dresses and costumes during those early years but, when the Depression came and my dad was out of work for a spell, went back to dressmaking rather more seriously in order to help out, and I suppose my seven-and-sixes must have been quite a help.

When I was eleven the pattern of my young career changed a little. I still carried on with the solo club singing, but I also joined a juvenile troupe with the ringing title of Madame Harris’s Kracker Kabaret Kids, and that was when, for professional purposes, I changed my name.

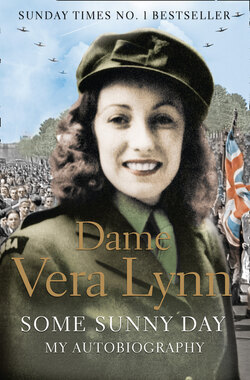

I never doubted that I was going to be a singer, and the instinct that had prompted me, when I was very tiny, to sing ‘Dream Daddy’ and follow it up with ‘I’ve Got a Real Daddy Now’ suggested that I ought to adopt a more comfortable— and more glamorous—stage name than Vera Welch. The main concern was to find something that was short and easily remembered, and that would stand out on a bill—something that would allow for plenty of space round each letter. We held a kind of family conference about it, and we found the answer within the family too. My grandmother’s maiden name had been Lynn; it seemed to be everything a stage name ought to be, but at the same time it was a real one. From then on, I was to be Vera Lynn.

In spite of its exotic name, Madame Harris’s Kracker Kabaret Kids was run from a house in Central Park Road, East Ham. As a juvenile troupe it prospered, and it quickly outgrew Madame Harris’s front parlour and transferred its activities, every Saturday morning, to the local Salvation Army hut; we used to pay sixpence each towards the cost of hiring it. I don’t know exactly how Madame Harris advertised the tuition she offered, but it’s my guess that she must have been an early exponent of ‘Ballet, Tap and Acro.’, that faintly ridiculous-sounding description you used to see on local advertising boards and among the small ads in local papers. Acrobatic I certainly was, with my long legs and my ability to kick high; while Pat Barry’s wisdom in insisting on my doing some tap dancing meant that I was halfway there as far as dancing was concerned. After a while I used to teach the kids while Madame Harris banged away at the piano. In fact it became something of a family concern, for my mother and Mrs Harris, between them, made all the costumes for our shows.

The troupe was a very busy performing unit, working the clubs as I had always done, but going rather farther afield, usually travelling in a small coach. On a trip to Dagenham once the driver got it into his head that he had to get us there in a great hurry, and drove like a madman all the way. We were terrified, and I seem to remember that we spent most of the journey screaming. He must have been driving very badly, because on the whole children are only aware of that kind of danger when it gets physically alarming, and I have a very clear recollection of being pitched all over the place. When you consider how much higher off the ground all the cars and buses were in those days, you can understand our certain belief that we were going to turn over. How we managed to dance and sing properly at the end of it I can’t think.

The other trip that sticks in my mind was part of what turned out in the end to be a rather longer stay away from home. It must have been during the Christmas holidays one year, because we’d been booked to do three nights in pantomime at—wait for it—the Corn Exchange, Leighton Buzzard. I don’t know whether the extra distance was a strain on the Kracker Kids’ finances, or whether the coach contractor was out of favour after the Dagenham Grand Prix run, or what, but this time we’d hired a vegetable van, with a flap at the back, to take us to and from the engagement. The arrangement lasted one night only. You know that old tag line ‘We had one but the wheel came off’? Well, it did, somewhere out on the edge of London where the tramlines ended. We were on the way home in the small hours of the morning when one of the wheels of this van came off, and there we were, a bunch of kids and a few mums stranded in a freezing street in some unfamiliar suburb. Keeping ourselves warm was the main problem, and we ran up and down for what seemed like hours, trying to keep our circulations going while we waited for the first tram to come along.

Eventually we got home at about six in the morning, though God knows what sort of state we were in, and we somehow went back to Leighton Buzzard the next night. But Mrs Harris decided we weren’t going to take any more risks and she found somewhere for us to stay for those two nights. All I can remember of our dubious accommodation is that we had to go up a winding staircase and all the girls were put in one room, the boys in another and the mums somewhere else, and in the middle of everything my mother was wandering about with a spoon in one hand and a bottle of syrup of figs in the other, dosing us one by one. This was in the heyday of parental belief in laxatives, of course, and what with that and the candles we had to carry to find our way to the loo it was like something out of Oliver Twist. Now I stop to think about it, the Leighton Buzzard Corn Exchange itself must have been pretty Dickensian, because all the backstage passages were unlit, and we had to use candles to find our way around the rambling passages. That must have been the first occasion when entertaining other people caused me to spend a night away from home. I couldn’t possibly have guessed then that eventually I should lose count of the times that happened, and that for part of my life that would be the rule rather than the exception.

I’m sure I was too busy concentrating on the job in hand to think of things like that, and in any case I always took my career a step at a time. It was very much a matter of steps then, too, for with one or two exceptions we were a strong dancing team. Which doesn’t mean we were short of soloists. Apart from myself there was Leslie, a boy soprano, who eventually made some records as Leslie Day, ‘the 14-year-old Wonder Voice Boy Soprano—Sings with the Perfect Art of a Coloratura Soprano’. My cousin Joan was in the troupe, too. Where I was tall and thin, she was short and tubby. She didn’t go on with it after the troupe days ended—she was my mother’s sister’s daughter, and had been rather pushed into it—but she had a terrific voice, and used to sing meaty songs like ‘The Trumpeter’. Unfortunately, she couldn’t dance to save her life. We used to try to teach her, but she’d just clop from foot to foot, saying, ‘I hate this, I hate it.’ Another boy, Bobby, who was a future Battle of Britain pilot, was a kind of juvenile lead, and we had little Dot, Bobby’s sister, who was tiny and sang Florrie Forde numbers and one or two Marie Lloyd songs, like ‘My Old Man Said Follow the Van’. Eileen Fields was another soubrette type. She and I would do duets occasionally—we dressed up as an old couple for one of them and sang ‘My Old Dutch’. Mrs Harris’s daughter, Doreen, was a good singer too, and in fact she practically ran the troupe; later on she became the wife of Leon Cortez, an actor who went on to appear in Dixon of Dock Green, The Saint and Dad’s Army in the 1960s. Doreen and I were the ones who went on into the profession itself, and when Doreen left to start broadcasting Mrs Harris asked me to take over instead. Soon after that, Mrs Harris packed it in altogether, and I took over the school for a year until I, too, got involved in other things.

I was with the troupe for about four years, and had a lot of fun. Some of the children clearly had no liking for it and no talent, and had merely been conscripted into it by ambitious mothers, but on the whole I don’t think we can have been too bad. We certainly did plenty of work, especially during the school holidays, when we often did shows on the stages of the big local cinemas. As juveniles we were subject to fairly strict controls and licensing regulations; you had to be over fourteen to appear on public stages after a certain hour at night without a licence, which ruined our chances when cousin Joan and I went in for a competition once. We were both under age and neither of us had a licence, but we got through to the semifinal without anyone bothering to check up. Then they said, ‘When you come tomorrow you’ll have to bring your birth certificate with you,’ but they said it to Joan and not to me. They never said it to me because I looked fourteen, even though I wasn’t. But they wanted Joan’s birth certificate, and that would have given the show away. We tried for hours to work out some way round it, but in the end we had to admit defeat, so that was us out of the competition, even though we felt we had a good chance of winning.

I don’t suppose ‘That’s show business’ had become a common phrase by that time, but presumably I accepted that setback (if that’s what it was) as simply one obstacle which time would remove. For in due course I would be fourteen and such problems wouldn’t arise.

I would also be free to leave school. Fourteen was the official leaving age, though you could stay on another year if you wanted to. The drama teacher begged me not to leave, because she wanted to put me into all sorts of productions, but all I wanted was to get away from school. Once I’d left, of course, I began wanting to go back. I realized I’d wasted a lot of precious time by not concentrating; I felt ignorant, and I wanted to return and make up for it.

Not that I ever doubted for a moment that I was going to be a professional singer. Judging by the way she stood over me while I learned my songs, by the way she helped with my costumes and by the way she came with me to whatever show I was doing, whichever club I was working at, I don’t think my mother could have doubted it either. But when I left school she wavered, offering the classic and very reasonable objection that there wasn’t enough security in the life of a professional popular singer. Actually her plan seemed not to have been for me to work at all in the ordinary sense, but to stay at home and help her while carrying on as usual—only more actively—in the clubs. In other words I was to continue to do as much singing as I could get, but that I wasn’t to regard it as my profession.

I didn’t fancy that, because the girl next door had stayed at home after she left school, and in no time at all she seemed to have turned into an old maid. I didn’t want to be like that, so I decided I ought to have a job and I went and signed on at the Labour Exchange. It took them six weeks to come up with something, by which time I’d already lost any enthusiasm for the idea before I even went to a little factory at East Ham to start sewing on buttons for a living. I sat down with a number of other young girls, but we weren’t even allowed to talk. When lunchtime came I went into a little back room with my sandwiches and felt thoroughly miserable. The day seemed never ending.

When I finally did get home, my dad asked me how I’d got on.

‘Horrible,’ I said. ‘You must do this and you mustn’t do that. I don’t want to go back there any more.’

‘How much do you get?’ he asked.

‘Six-and-six.’

‘A day?’

‘No, for the week.’

‘Be damned to that,’ he said. ‘Why, you can earn more than that for one concert. You’re not going back there. What do you have to put up with it all for?’

So I never did go back, and I got a postal order for one-and-a-penny for my day’s work. I can’t say that at this stage I really had any idea myself what I wanted to do with my life. Children thought differently in those days to how they think today. Now they have ideas of what they want to do, but in those days you just went along with what your mother or father said.

But it was fairly typical of my father to side with me over the button factory. He was very much the one for going along with the wishes of his children. In fact he was an enormously easy-going man altogether. While my mother was the sort who, for some years to come, would wait up for me after a show so that I dare not linger or go to any of the many parties that were held, Dad would have said, ‘Go on, mate, do as you like, mate; enjoy yourself, I’m going off to bed.’ Only two things ever really seemed to upset him, and they were quite trivial. If you gave him a cup of tea that hadn’t been sugared he’d carry on as if you’d tried to poison him; and he hated being expected to go to tea at anybody else’s home.

It was the strong principles of my mother that laid down the rules that gave our household and my childhood their peculiar flavour. For example, most families at that time, no matter what their religious views, tended to encourage the children to go to Sunday school, if only to get them out of the way for an hour or so on a Sunday. We were positively not allowed to go to Sunday school. My mother didn’t think it was right to go to church or Sunday school during the day on Sunday, and then go singing in the clubs on Sunday night. I think she was wrong, but that’s what she believed, and there seemed nothing strange about it at the time.

At the latter end of my period with Mrs Harris’s juvenile troupe I was starting to work quite hard as a young entertainer. By the time I left school at fourteen I had, to all intents and purposes, already been earning my living as a performer for seven years, and after that one day’s orthodox employment I never thought of doing anything else. I more or less ran the troupe, and I sang and danced with it, but I still went out solo as well. The engagements were mainly club dates, as they had always been, but I was beginning to add slightly more sophisticated cabaret bookings to my diary—private social functions and dinners. On a ticket to one of them I suddenly found I was being described as ‘the girl with the different voice’. That was a label I should hold on to, I realized. It was nothing spectacular, but it was progress, a kind of hint that I wasn’t to remain working round the clubs for ever, and that I could expect in time to move on to something else.

That something else was to start when I was fifteen, and doing a cabaret spot at Poplar Baths. It was a nerve-racking evening when everything happened at once: I had a foul cold, I encountered my first microphone and I was heard by Howard Baker, the king of the local bandleaders. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the moment my life really took off.