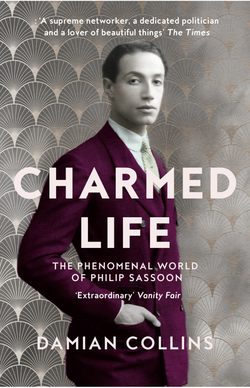

Читать книгу Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon - Damian Collins - Страница 8

2 • THE GENERAL’S STAFF •

ОглавлениеFighting in the mud, we turn to

Thee In these dread times of battle Lord,

To keep us safe, if so may be,

From shrapnel snipers, shells and sword.

Yet not on us – (for we are men

Of meaner clay, who fight in clay) –

But on the Staff, the Upper Ten,fn1

Depends the issue of the day.

The Staff is working with its brains

While we are sitting in the trench;

The Staff the universe ordains

(Subject to Thee and General French).

God help the staff – especially

The young ones, many of them sprung

From our high aristocracy

Their task is hard, and they are young.

O Lord who mad’st all things to be

And madest some things very good

Please keep the extra ADC

From horrid scenes, and sights of blood.

See that his eggs are newly laid

Not tinged as some of them – with green

And let no nasty drafts invade

The windows of his limousine.

Julian Grenfell,

‘A Prayer for Those on the Staff’ (1915)1

The First World War thundered into the summer of 1914 from a clear blue sky. On the morning of 28 June the heir of the Emperor of Austria, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo by a young ‘Yugoslav nationalist’, Gavrilo Princip.fn2, 2 In thirty-seven days Europe went from peace to all-out war at 11 p.m. on 4 August. People at that hour had little comprehension of the magnitude of the decision that had been made, and how it would shatter the lives of millions of people.

Doom-mongers in the press and the authors of popular fiction had, however, been predicting war for years. The growing military rivalry between the powers and the ambition of Germany in particular, they believed, would inevitably lead to conflict. H. G. Wells, a friend and near neighbour of Philip Sassoon’s in Kent, had also made this prediction in his 1907 novel War in the Air.

As relations between the nations of Europe deteriorated in late July, people started to prepare for war. On 28 July, the day Austria declared war on Serbia, Philip Sassoon’s French Rothschild cousins sent a coded telegram to the London branch of their family asking them to sell ‘a vast quantity’ of bonds ‘for the French government and savings banks’. The London Rothschilds declined to act, claiming that the already nervous state of the financial markets would make this almost impossible, but they secretly shared the request with the Prime Minister, Asquith, who regarded it as an ‘ominous’ sign.3

On 3 August Philip Sassoon sat on the opposition benches of a packed House of Commons to listen to the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, update Parliament on the gravity of the situation in Europe. Britain stood ready to honour its commitments to the neutrality of Belgium, and to support France if it were to be the victim of an unprovoked attack. Sir Edward argued to cheers in the House that if a ‘foreign fleet came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing’. It was a scene that Philip could all too easily envisage, as it was one that might be observed standing on the terrace of his new house at Lympne. The prospect of a naval conflict near the Channel, and fighting on land, of the kind that the Foreign Secretary described would also place his own parliamentary constituency in south-east Kent almost exactly on the front line. For Britain to fight in defence of France, the home of his mother and where he had spent so much of his own life, would be for Philip a just cause.

His first thought following the outbreak of war was for the safety of his sister Sybil and her husband who were in Le Touquet, on the return journey from their honeymoon in India. They had stopped off there so that Rock could play in a polo match, but now there were reports of chaos at Channel ports like Boulogne, where people were trying desperately to get home. So Philip’s first act of the war was to dispatch his butler Frank Garton to France with a bag of gold sovereigns to ensure their safe passage home.

Conscription into the British army would not be introduced until 1916, but Philip was not faced with the dilemma of when or whether to volunteer for the armed forces. As an officer in the Royal East Kent Yeomanry reserve force, he received his mobilization orders the day following the declaration of war; Philip was one of seventy Members of Parliament who were called up in this way. There was no question of MPs who volunteered to fight being required to give up their seats. Philip believed that as a young man he was better placed to serve the interests of his constituents in wartime by joining up with the armed forces than by working in Westminster.

Philip’s Eton and Oxford friends, such as Patrick Shaw Stewart, Edward Horner and Charles Lister, volunteered. Julian Grenfell was already a professional soldier as a captain in the Royal Dragoons. Lawrence Jones, who also served as a cavalry officer, remembered that ‘whereas Julian went to war with high zest, thirsting for combat, and Charles with his habitual selflessness to a cause, Patrick had it all to lose … but knowing the risks, let go his hold of them and went cheerfully to war’.4

Philip also went cheerfully, and even as late as 1915 he wrote to Julian Grenfell’s mother Lady Desborough from France, telling her, ‘It is so splendid being out here. The weather is foul – the climate fouler and the country beyond words and nothing doing – but it is all rose coloured to me.’5 Philip did not have the swagger of a natural soldier. A fellow officer recalled walking into a French town with him when they met a young woman with bright-red hair. ‘Philip wishing to pay her a compliment said to her “vous avez de très jolies cheveux Mademoiselle”. But as he said it he tripped up over his silver spurs and fell on his face on the pavement.’6 Men like Julian Grenfell were, however, in their element at the front. Grenfell wrote to his mother, ‘I adore war. It is like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic. I’ve never been so well or so happy. Nobody grumbles at one for being dirty. I’ve only had my boots off once in the last ten days; and only washed twice.’7

Philip did not join this band of brothers fighting at the front. He was held training with his regiment until February 1915, when he was transferred to St Omer to work as a staff officer at the headquarters of Field Marshal Sir John French, the Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. The British were fighting in alliance with the forces of France along a united front, and so coordination and understanding between the commanders was a necessity. Philip Sassoon’s family and political connections in London and Paris, as well as his perfect command of the French language, made him an excellent choice to serve on the British staff.

The staff soon became the focus of resentment among the soldiers serving at the front. While the latter endured the mud, wet, cold and death in the trenches, the staff officers operated from headquarters based at French chateaux many miles behind the lines. In the Blackadder version of the history of the First World War, staff officers like Captain Darling are characterized as being rather arrogant and effete, leading a life of relative comfort and security. Similarly in the 1969 satire Oh! What a Lovely War the immaculately dressed staff officers play leapfrog at General Headquarters (GHQ) while the men die at the front. As the war went on the soldier poets came to curse the ‘incompetent swine’8 on the staff whom they blamed for the failures of military strategy, and Julian Grenfell in one of his poems went as far as to accuse some of the young officers of being too ‘green’ to fight.9

Yet many staff officers lost their lives during the war, and they were at risk from direct fire, particularly from enemy shells, both when they visited advanced positions closer to the front and on the occasions when they were targeted at GHQ itself. Philip worked long hours, but while the small wooden hut at GHQ that served as his personal quarters was not at all luxurious, it was not the trenches. It was a distinction he recognized, writing to Lady Desborough during a period of particularly bad weather, ‘I can’t imagine how those poor brutes in the trenches stick it out. I simply hate myself for sleeping in a bed in a not so warm house.’10 But other men of similar status had opted to serve at the front, and twenty-four MPs would be killed in action during the war. Raymond Asquith, the son of the Prime Minister, had refused a transfer to a position on the staff, and would later die leading his men in battle. Philip had simply obeyed his orders; he was mobilized at the start of the war, and until February 1915 was preparing to fight at the front. He had never sought to avoid combat, and it was his skill as an accomplished staff officer that kept him at GHQ. Nonetheless, some would later question his war record, with the Conservative politician Lord Winterton wondering in his diary after dining with Philip, ‘which is more disgraceful, to have no medals like [the Earl of] Jerseyfn3 who has shirked fighting in two wars, or to have them like Philip Sassoon without having earned them’.11

After his initial placement on Sir John French’s staff, Philip was promoted to serve as aide-de-camp (ADC) to General Rawlinson, the commander of IV Army Corps. The IVth was part of the British Expeditionary Force and had seen heavy fighting in Belgium at the first Battle of Ypres, and in early 1915 would take the lead at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. Philip had Eton in common with Rawlinson, but otherwise their lives had been completely different; the general was a professional soldier who had passed out from Sandhurst before Sassoon was born, and he had served in Lord Kitchener’s campaign in the Sudan in 1898–9. In August 1914 optimists had predicted that the war might be over by Christmas, but as the stalemate of trench warfare became established on the Western Front, the generals had to plan for a long campaign. Rawlinson believed that the war would be won only by attrition, and by early 1915 Philip agreed that the Germans would have to be driven back trench by trench until the Allies reached their border, rather than by some great breakthrough that would deliver a knock-out blow. He was also concerned that any eagerness for an early peace settlement before Germany had been clearly defeated would leave it strong enough to start another war in fifteen or twenty years.12

The day-to-day reality of this strategy of attrition was found in the death toll at the front. Philip would anxiously look for the names of his friends, as each morning he went through the lists of the dead and missing. In May 1915 Julian Grenfell received a head injury from a shell fragment at Railway Hill near Ypres. The initial prognosis was positive, but his condition deteriorated and he died on 26 May at the military hospital at Boulogne. When the notice of his death was placed, The Times printed a poem he had recently completed and sent to his mother in the hope she might be able to get it published. Entitled ‘Into Battle’, it extolled the honour and glory of the fighting, with Mother Nature urging on the soldiers with the words, ‘If this be the last song you shall sing, / Sing well, for you may not sing another.’

Philip was greatly affected by the loss of Julian, but it was nearly a month before he wrote to Lady Desborough. ‘I have tried to write to you every day since Julian died, but have been fumbling for words … ever since I had known him in the old Eton days I had the most tremendous admiration for him and always regretted that circumstances and difference of age had prevented our becoming more intimate.’ Julian had been only a few months older than Philip, although he was a more senior figure in the hierarchy at Eton, and almost the epitome of the heroic Edwardian English schoolboy. Philip’s choice of words reflected the distance in their relationship, but underlined how he looked up to Julian and desired his approval. It was as if for Philip that personal acceptance by Julian represented the broader appreciation of English society of his character and ability. Philip continued his letter to Lady Desborough by quoting from the war poet Rupert Brooke, who had himself died just the month before, telling her that Julian had left a ‘white unbroken glory, a gathered radiance, a width, a shining peace, under the night’.13 Julian had seemed so indestructible, it was barely credible to Philip that he could be gone. ‘Such deaths as his’, he told Lady Desborough, ‘strengthen our faith – it is not possible that such spirits go out. We know that they must always be near us and that we shall meet them again.’14

There was a curious epitaph to Julian’s death a few weeks later, during the Battle of Loos. One of the reservist cavalry regiments was saddled up, night and day, in the grounds of General Rawlinson’s chateau, ready in case a breakthrough in the line was achieved and the cavalrymen would be called on to gallop through the gap. Lawrence Jones, who was among their number, recalled:

After a sleepless night spent attempting to get some shelter under juniper bushes from the incessant rain, we were gazing, chilled and red-eyed, at the noble entrance of the chateau from which we expected our orders to come forth, when a very slim, very dapper young officer, with red tabs in his collar and shining boots, began to descend the steps. It was Philip Sassoon, ‘Rawly’s’ ADC. I have never been one of those to think that Staff Officers are unduly coddled, or that they should share the discomforts of the troops. Far from it. But there are moments when the most entirely proper inequality, suddenly exhibited, can be riling. Tommy Lascelles, not yet His or Her Majesty’s Private Secretary, but a very damp young lieutenant who had not breakfasted, felt that this was one of those moments. Concealed by a juniper bush he called out, ‘Pheeleep! Pheeleep! I see you!’ in a perfect mimicry of Julian’s warning cry from his window when he spied Sassoon, who belonged to another College, treading delicately through Balliol Quad. The beauteous ADC stopped, lifted his head like a hind sniffing the wind, then turned and went rapidly up the steps and into the doorway. Did he hear Julian’s voice from the grave? … We shall never know.15

Julian’s younger brother Billy was killed in action on 30 July leading a charge at Hooge, less than a mile from where Julian had been wounded. Billy’s body was never found, and without a known grave he was remembered after the war on the Menin Gate memorial at Ypres. Philip had grown up with Billy at Eton and at numerous weekend parties at Taplow, and he sat down in his quarters once again to write the most painful of letters to Lady Desborough:

It was only about a fortnight ago that I had a letter from him saying that he was so bored at being out of the line and aching to get back into the salient – I rushed up to Poperinge – but he had left that morning for the trenches – now I shan’t ever see him. This has taught me not to look ahead – but I had allowed myself somehow to look forward to Billy’s friendship as something very precious for the future – and he has left a blank that can never be filled. I look back on all the pleasant hours we spent together. I have that possession at any rate. How I shall miss him.16

Philip’s words reflect the more conventional friendship he had enjoyed with Billy, compared to that with Julian, one that was not marked by the need for acceptance.

In late August 1915, Charles Lister, a lieutenant in the Royal Marines, died in the military hospital at Mudros from wounds sustained in the fighting at Gallipoli. Lister had sailed out to the eastern Mediterranean with Rupert Brooke and Patrick Shaw Stewart, and while Shaw Stewart survived this doomed campaign he would later succumb at the Battle of Cambrai in 1917 along with Edward Horner. ‘Would one ever have believed before the war’, Philip wrote to a friend, ‘that one could have stood for one single instant the load of pain and anxiety which is now one’s daily breath. I find that, although I can study the casualty list without ever seeing a name I know – for all my friends have been killed – yet nevertheless one feels as much for others as for oneself – just a blur of grief: and one wakes every morning feeling one can hardly bear to live through the day.’17

The deaths of these young men led to a series of publications to commemorate their short, heroic lives. Ronald Knox quickly produced a biography of Patrick Shaw Stewart, and another book, E. B. Osborn’s The New Elizabethans, included essays on the Grenfell boys, Charles Lister and others. The title was inspired by Sir Rennell Rodd’s vision of Lister as belonging to the ‘large-horizoned Elizabethan days, and he would have been in the company of Sidney and Raleigh and the Gilberts and boisterously welcomed at the Mermaid Tavern’.fn4, 18

Not all of their contemporaries recognized these romantic portraits of their friends. Lawrence Jones recalled:

A legend has somehow grown up, that Julian was one of a little band of Balliol brothers knightly as they were brilliant who might, had they survived, have flavoured society with an essence shared by them all. As far as [Charles Lister, Patrick Shaw Stewart and Edward Horner] and Julian are concerned, the legend is very wide of the mark. Apart from their delight in each other’s company, and common gallantry in the exacting tests of the war, few men could have been less alike in temperament, character and outlook.19

Duff Cooper, another Eton and Oxford contemporary, wrote to Knox to protest about his biography of Shaw Stewart. In his diary he complained, ‘He never consulted me … nor asked either me or Diana for letters. This irritates me. The book as it stands is bad and dull.’fn5, 20

Yet one of these testaments to the doomed youth of the war would remain beyond reproach – Lady Desborough’s tribute to her sons, Pages from a Family Journal. This great book, running to over six hundred pages, published in 1916, was an intimate portrait of their lives from early childhood. It was, in the words of Lord Desborough, ‘intended for Julian and Billy’s brothers and sisters and for their most intimate friends’. Upon receiving his copy, Philip Sassoon told Lady Desborough that ‘it will be a tribute for all time to those two splendid joyous boys whose loss becomes more unbearable every day. One would like to have included every letter they ever wrote … I keep rereading their letters and your accounts of them until I cannot believe that they are gone.’21

For many people, this belief that their loved ones could not really be gone took them in search of the intervention of spiritualist mediums. The number of registered mediums in England would more than double by the early 1920s, compared with pre-war figures.22 Shortly after the end of the war, following the death of a pilot friend in a plane crash, Philip Sassoon approached an old family friend, Marie Belloc Lowndes,fn6 and begged her ‘to write to Sir Oliver Lodge … to ask for the address of a medium’.23 Lodge was a Christian spiritualist who had come to particular prominence following the publication in 1916 of his sensational book Raymond, or Life and Death.fn7 The book detailed his belief that his son Raymond, who had been killed in action in Flanders in 1915, had communicated with him through séances that he and his wife had attended with the medium Gladys Osborne Leonard. Marie Belloc Lowndes secured the details from Sir Oliver of a medium in London and she accompanied Philip on the visit. She recalled that they

drove to a road beyond Notting Hill Gate, and stopped in front of a detached villa. We were admitted by a middle-aged woman, who led us into a room which contained some shabby garden furniture … after a few moments, the medium went into a trance, and from her lips there issued a man’s voice, describing a fall from a plane, and the instant death of the speaker. The same voice then made a strong plea concerning the future of a group of children he called the ‘kiddies’, and who, he was painfully anxious, should not be parted from their mother. Meanwhile Philip remained silent, staring at the medium. After a pause the same man’s voice as before issued from the sleeping woman’s lips. Again the accident was decried and there then followed an allusion to a pair of flying boots, which the speaker hoped Philip would find useful. When we were back in his car, Philip Sassoon turned to me and exclaimed, ‘The voice which spoke to me was the voice of the man who was killed flying in Egypt.’ Did you understand the allusion to his flying boots? He said, ‘Of course I did. I bought his flying boots after his death.’24

On 29 October 1915 Philip was in Folkestone harbour, ready to return to France after a brief period of home leave. He waited to board his ship at the simple café on the harbour arm, which catered for service personnel. It was run by two sisters, Margaret and Florence Jeffery, and Mrs Napier Sturt, who dispensed free refreshments and kept visitors’ books which they asked all their guests, servicemen and statesmen of all ranks, to sign. Philip was happy to oblige along with the group of staff officers with whom he was travelling.25 Looking around, he could see how Folkestone had been transformed by the war. It had been an elegant resort town from where the wealthy had journeyed to the continent on the Orient Express, which had descended with its passengers into the harbour station. Now it was the major embarkation point for servicemen to France, and over ten million soldiers would pass through the town on their way to and from the trenches of the Western Front. In addition to this the town was home to tens of thousands of Canadian servicemen stationed at Shorncliffe Barracks, and thousands of refugees from Belgium who had fled from the advancing Germans in August 1914.

The pre-war world was gone for ever and in October 1915 it wasn’t clear when peace would return, or if Britain and its allies would be victorious. The Germans were winning against the Russians in the east, and in the west they were fighting in French and Belgian territory, not on their own soil. The British attempt to open up the war in the east at Gallipoli had failed and in November 1915 brought about the resignation from the cabinet of Winston Churchill, whose idea it had been. A further setback on the Western Front at the Battle of Loos created pressure for a change in the direction of the war effort, and on 3 December General Sir Douglas Haig replaced Sir John French as commander of the British forces in France. This change of leadership would have a sudden and profound impact on Philip Sassoon. Haig, upon taking up his new post, invited Philip to work for him as his private secretary at GHQ. The war had now given Philip something he had sought in peacetime – a chance to perform a meaningful role at the centre of great events.

On 31 March 1916 Haig established his personal headquarters at the Château de Beaurepaire, in the hamlet of Saint Nicolas, a short distance from the beautiful town of Montreuil-sur-Mer, and about 20 miles south of Boulogne. The communications nerve centre of GHQ was based in the historic Citadel at Montreuil, but the whole town became an English colony for the remainder of the war. The Officers’ Club in the Rue du Paon was believed to have one of the best wine cellars in Europe,26 and tennis courts were constructed between the ramparts that surrounded the Citadel.

Montreuil was chosen because it was centrally placed to serve as the communications centre for forces across a front stretching from the Somme to beyond the Belgian frontier. It was also a small town of only a few thousand inhabitants, and no great distractions for the officers and men stationed there.

Montreuil and the Château de Beaurepaire would be Philip’s principal base for the rest of the war, although for the launch of new battle offensives GHQ could move to an advanced position, often in a house closer to the front line, or in some railway carriages parked in a nearby siding. Philip would also accompany Haig to conferences of the British and French leaders and represent him at meetings in London and Paris. There was a dynamism to working for Haig that suited Philip’s energetic personality: cars and drivers on standby to rush between meetings, special trains and steamships ready to convey the ‘Chief’ at any hour, the King’s messenger service available for the express delivery of important messages or specially requested luxury items for an important dinner.

Philip’s working routine was set around Haig’s. He would be at his desk before 9 a.m. each morning, breaking at 1 p.m. for lunch, which lasted for half an hour. In the afternoon, Philip would typically accompany Haig to meetings at GHQ or to visit ‘some army or corps or division’ in the line.27 After returning to Beaurepaire they worked up to dinner at 8 p.m., then went back to the office at 9, until about 10.45 p.m. Brigadier-General John Charteris, who was Haig’s Chief Intelligence Officer, remembered that ‘At this hour [Haig] rang the bell for his Private Secretary, and invariably greeted him with the same remark: “Philip – not in bed yet?” He never changed this formula, and if, as did occasionally happen, Philip was in bed, he always used to say to him next morning: “I hope you have had enough sleep?” There were only rare occasions when this routine of the Commander-in-Chief’s day was broken by even a minute.’28

Sassoon and the general developed a good working relationship, and Haig came to regard Philip as a ‘very useful private secretary’.29 Robert Blake, who would later edit Douglas Haig’s private papers, noted that ‘Haig did not talk much himself but he enjoyed gaiety and wit in others, and he appreciated conversational brilliance. This partly explains his paradoxical choice of Philip Sassoon as his private secretary.’30 There was criticism from some of the other staff officers of Haig’s decision. Philip was in their eyes a politician who had not been trained at Sandhurst like the rest of them, or seen any military service, yet he was now to have privileged access to the Commander in Chief at all hours. According to Blake, they saw Philip as a ‘semi-oriental figure [who] flitted like some exotic bird of paradise against the sober background of GHQ’.31 Some also felt he had been preferred because his uncle Leopold Rothschild was a friend of Haig’s. Leopold, with Philip’s assistance, would certainly make sure that Haig was kept well supplied with food parcels from his estate, which may have added credence to these mutterings.

Philip’s appointment was due in part to the reputation he had earned during the war as an efficient and effective staff officer; but there were plenty of those for Haig to choose from. As a fluent French-speaker, and a relative of the French Rothschilds, Philip was also able to assist in the liaison between Haig and the military commanders and senior politicians of France. His contacts in Westminster and the London press were similarly invaluable. Douglas Haig had learnt from the removal of Sir John French as Commander in Chief that the position of a general in the field could soon become vulnerable without powerful supporters at home.

But while Philip knew the leading politicians in London, he had not yet established himself as a figure in their world. In January 1916 Winston Churchill visited Haig at GHQ, which he found deserted, except for Sassoon sitting outside the Chief’s office, ‘like a wakeful spaniel’.32 As a former serving officer in the Hussars, Churchill, free from ministerial responsibility, now wanted a command on the front line in France. A few days after Churchill’s visit, Philip wrote to H. A. Gwynne, the editor of the Morning Post, informing him that ‘Winston is hanging about here but Sir D. H. refuses to give him a Brigade until he has had a battalion several months. It wouldn’t be fair to the others and besides does he deserve anything? I think not, certainly not anything good.’33

Philip was now in the front line of the war within the war – that between Britain’s leading politicians and the military commanders in France over the direction of the conflict. At its heart was an argument that continues to this day: whether it was poor generalship or poor supply that was prolonging the war. One of Philip’s allies in this new front was Lord Esher, a member of the Committee for Imperial Defence, who had been an éminence grise in royal and military circles for many years. Regy Esher ran an informal intelligence-gathering network based on gossip and insight collected from his well-connected friends in London and Paris. His style and experience suited Philip perfectly. Esher was also a sexually ambiguous character, who made something of a habit of befriending young men like Philip Sassoon. There is no romance in their letters, which while full of gossip were largely focused on the serious matter of winning the war. However, Philip certainly opens up to Regy, suggesting a strong mutual trust, and a relationship similar to those he formed with other older friends, who became a kind of surrogate family for him. One letter in particular to Esher is full of melancholic self-reflection. ‘To have slept with Cavalieri [Michelangelo’s young male muse], to have invented wireless, to have painted Las Meninas, to have written Wuthering Heights – that is a deathless life. But to be like me, a thing of nought, a worthless loon, an elm-seed whirling in a summer gale.’34

Esher advised Philip on the importance of his role as a gatekeeper and look-out for the Chief against the interference of government ministers in Whitehall. He told him in early 1916 that the ‘real crux now is to erect a barbed wire entanglement round the fortress held by K,fn8 old Robertsonfn9 and the C[ommander] in C[hief] … But subtly propaganda is constantly at work.’35

This ‘propaganda’ was emanating from Churchill, F. E. Smithfn10 and David Lloyd George, who had started to question the strategy of the generals; in particular they shared a growing concern at the enormous loss of life on the Western Front for such small gains, and debated whether some other means of breaking the deadlock should be found. The generals on the other hand firmly believed that the war could be won only by defeating Germany in France and Belgium, and were against diverting resources to other military initiatives. Churchill in this regard blamed Lord Kitchener and the generals in France for the failure of his Gallipoli campaign, because he felt they had not supported it early enough and with the required manpower to ensure success.

These senior politicians also believed that the generals were seeking to undermine confidence in the government through their friends in the press, so that any blame for military setbacks fell on the ministers for their failure to supply the army with sufficient trained men, ammunition and shells. Churchill was highly critical of what he saw as

the foolish doctrine [that] was preached to the public through the innumerable agencies that Generals and Admirals must be right on war matters and civilians of all kinds must be wrong. These erroneous conceptions were inculcated billion-fold by the newspapers under the crudest forms. The feeble or presumptuous politician is portrayed cowering in his office, intent in the crash of the world on Party intrigues or personal glorification, fearful of responsibility, incapable of aught save shallow phrase making. To him enters the calm, noble resolute figure of the great Commander by land or sea, resplendent in uniform, glittering with decorations, irradiated with the lustre of the hero, shod with the science and armed with the panoply of war. This stately figure, devoid of the slightest thought of self, offers his clear far-sighted guidance and counsel for vehement action, or artifice, or wise delay. But this advice is rejected; his sound plans put aside; his courageous initiative baffled by political chatterboxes and incompetents.36

In 1916 Philip Sassoon would be the most significant of those ‘innumerable agencies’, taking on the responsibility for liaising with the media on behalf of Douglas Haig. His most important relationship was with the eminent press baron Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Times and the Daily Mail, whose regard for military leadership was as great as his general contempt for politicians. Northcliffe had started from nothing to become the greatest media owner of the day, and could boast that half of the newspapers read every morning in London were printed on his presses. He was at this time, according to Lord Beaverbrook’s later account, ‘the most powerful and vigorous of newspaper proprietors’.37

Philip had the emotional intelligence to understand that the great press baron expected to be appreciated. He would facilitate Northcliffe’s requests to visit the front or for his journalists to have access to interview Haig. Philip would also write to thank him for reports in his papers that had pleased GHQ. The great lesson that Philip would learn from Northcliffe was that even people who hold great office cannot fully exercise their power without the consent of others, and that consent is based on trust and respect. The press had the power to apply external pressure which could lead people to question the competences of others. In this way they had helped to bring down Sir John French, and forced Prime Minister Asquith to bring the Conservatives into the government.

Northcliffe had complete faith in the army and in the strategy of the generals to win the war on the Western Front. He wanted to deal directly with Haig’s inner circle, and he knew that when he was talking to Philip Sassoon he was as good as talking to the Chief. Philip had good reason as he saw it to give his full support to Haig, and this was not just motivated by personal loyalty. Lloyd George had a reputation as a political schemer who had been the scourge of many Conservatives.fn11 Churchill was also hated by many Tory MPs for leaving their party to join the Liberals (in 1904), a decision that seemed to them to have been motivated by opportunism and desire for government office rather than by any high principle. After the failure of Gallipoli and Churchill’s resignation from the cabinet, Philip was also clear with Northcliffe that he was no Churchill fan, and was against his return to any form of influence over the direction of the war, ‘with his wild cat schemes and fatal record’.38

In early June 1916 Philip stepped ashore at Dover with Haig after a stormy Channel crossing from Boulogne which had left him terribly sea sick. On seeing the news that was immediately handed to the Commander in Chief, any remaining colour would have drained from his complexion. Lord Kitchener, the hero of the Empire and the face of the war through the famous army-recruitment posters, was dead. He had drowned when the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire, which was conveying him on a secret diplomatic mission to Russia, sank after striking a mine off the Orkney Islands. Philip had got to know Kitchener only since joining Haig’s team and found him to possess, ‘apart from his triumphant personality – all those qualities of sensibility and humour which popular legend has persistently denied him. He dies well for himself but how great his loss is to us the nation knows well and some people in high places will learn to realise.’39 Kitchener’s death blew a hole in the ‘barbed wire entanglement’ Lord Esher wanted to see protecting the military command from the politicians. Worse still, as far as GHQ was concerned, he was replaced as Secretary of State for War by Lloyd George.

The Battle of the Somme, which started on 1 July, brought further heavy losses on the Western Front: there were 60,000 casualties on the first day, with 20,000 soldiers killed. This was the worst day of casualties in the history of the British army, yet Haig was determined to press on with his campaign. Later in the month GHQ decided to mobilize press support for Haig ahead of any attempt by the new Secretary of State to interfere in military strategy. Philip Sassoon arranged for Lord Northcliffe to stay at GHQ, and he set up a meeting for him with Haig. The success of this encounter, Philip told Lord Esher, ‘will prove as good as a victory … One must do all one can to direct press opinion in the right channel.’40 Although he was sometimes baffled by the interest of the press in the day-to-day trivia of Haig’s life at GHQ, he remarked to Esher that ‘Apparently the British public have much more confidence in him now they know at what time he had breakfast.’41 Haig was more than happy with the initial results, noting with pleasure in a letter to his wife that his name was ‘beginning to appear in the papers with favourable comments! You must think I am turning into an Advertiser!’42

Northcliffe wanted Philip to stay in contact with him over the summer while he was holidaying in Italy and told him to send messages via the British Embassy in Rome and his political adviser in London, Geoffrey Robinson. He encouraged Philip to stay close to Robinson and to allow him to come and visit out at the front. He told him that Robinson was his closest adviser on the thoughts and actions of members of the cabinet: ‘It is our system that he should know them and I should not, which we find an excellent plan. They are a pack of gullible optimists who swallow any foolish tale. There are exceptions among them, and they are splendid ones, but the generality of them have the slipperiness of eels, with the combined vanity of a professional beauty.’43

The opening barrage from the politicians was delivered by Winston Churchill, who after leaving the cabinet had served at the front in early 1916, but by the summer had returned to London to speak up in the House of Commons as the champion of the soldiers serving in the trenches.fn12 On 1 August he prepared a memo for the cabinet, which was circulated with the help of his friend F. E. Smith. Churchill argued that, following the start of the Battle of the Somme, the energies of the army were being ‘dissipated’ by the constant series of attacks which despite the huge losses of life on both sides had failed to deliver a decisive breakthrough.44 This memo immediately captured the attention of Lloyd George. Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, tipped off Haig that ‘the powers that be’ were beginning to get a ‘little uneasy’ about the general situation, and Haig prepared a note in response to Churchill’s criticisms which was circulated to the War Committee, the cabinet committee that oversaw the national contribution to the war effort.45 The King visited GHQ on 8 August and discussed Churchill’s paper with Haig in detail. Haig recalled in his diary that he had told King George ‘that these were trifles and that we must not allow them to divert our thoughts from the main objective, namely “beating the Germans”. I also expect that Winston’s head is gone from taking drugs.’46

Philip Sassoon heeded Northcliffe’s request to keep him informed of developments at GHQ and wrote to tell him that ‘We have heard all about the Churchill Cabal from the King and his people who are out here this week … The War Committee are apparently quite satisfied now at the appreciation of the situation which the Chief had already sent them and proved a complete answer to Churchill’s damnable accusations.’ Philip then added suggestively, ‘Lloyd George is coming to dine here Saturday night. I shall be much interested to hear what he has to say. I do trust that he and Carsonfn13 will be made to realise how damaging any flirting with an alliance with Churchill would be for them. Do you think they realise this? Sufficiently?’47

On 14 August Lord Esher wrote to reassure and warn Philip that

No combination of Churchill and F. E. can do any harm so long as fortune favours us in the field. These people only become formidable during the inevitable ebb of the tide of success. It is then that a C in C absent and often unprotected by the men whose duty it is to defend him, may be stabbed in the back. It is for this reason that you should never relax your vigilance and never despise an enemy, however despicable.48

Philip certainly had complete faith in Haig’s strategy and the ongoing Battle of the Somme, writing to his uncle Leopold Rothschild the same day, ‘Everything is going very satisfactorily here and the whole outlook is good. If we can, as I hope, keep up combined pressure right into the autumn, the decision ought not to be far off.’

During Lloyd George’s visit to GHQ he reassured Haig that he had ‘no intention of meddling’.49 Yet, the following month, news reached Haig directly from the French commander General Foch that Lloyd George had been asking his opinion about the competence of the British commanders. Haig could not believe that ‘a British Minister could have been so ungentlemanly as to go to a foreigner and put such questions’.50 Philip Sassoon was given a full debrief on Lloyd George’s visit to see Foch, which could only have come directly from Haig, and he immediately set to work on Northcliffe. His response was designed to be personally wounding, saying that Lloyd George’s visit to both the British and French headquarters had been a complete ‘joy ride from beginning to end’. He also told Northcliffe that Lloyd George had been discourteous by keeping General Foch waiting an hour and a half for lunch, without giving an apology, and then he had asked him why the French guns were more effective than the British, which Foch refused to answer. Lloyd George also found only fifteen minutes of private time for Douglas Haig during his visit. ‘If this is the man some people would like to see PM,’ Philip told Northcliffe, ‘I prefer old Squifffn14 any day with all his faults. It is my private opinion that he has neither liking nor esteem for the C in C. He has certainly conveyed that impression to all. No doubt Churchill’s subtle poison has done its deadly work.’51

Philip’s intervention led to a series of articles in Northcliffe’s newspapers praising Haig and the work of the British army in France, and sniping at the ‘shirt-sleeved politicians’ who were interfering with the war. Philip’s efforts on behalf of his Chief were also coming to the attention of Lloyd George’s advisers, who warned him that Haig was ‘trying to get at the press through that little blighter Sassoon’.52

The growing pressure on GHQ for a real success in the field led to the use of tanks for the first time during the later stages of the Battle of the Somme, at Pozières. The idea of an armoured trench-crossing machine had first been suggested in October 1914 by Major Ernest Swinton, who was the official British war correspondent on the Western Front. It captured the imagination of Winston Churchill, who in early 1915 urged Asquith to allow the Admiralty to develop a prototype for a ‘land ship’. To help keep the programme secret, designs were developed under the misleading title of ‘water-carriers for Russia’. When it was pointed out that this could be abbreviated to ‘WCs for Russia’, that name was changed to ‘water-tanks’, then to ‘tanks’.53

Churchill had begged Asquith not to allow the machines to be used until they could be perfected and launched in large numbers and to the complete surprise of the Germans. Haig, however, was agitating to get them into the field as soon as possible, and their initial deployment in September 1916 met with limited success. Nevertheless, they caused yet more intrigue between the politicians and GHQ over who should take the credit for them. Northcliffe wrote to Philip on 2 October:

You may have noticed that directly the tanks were successful, Lloyd George issued a notice through the Official Press Bureau that they were due to Churchill. You will find that unless we watch these people they will claim that the great Battle of the Somme is due to the politicians. That would not matter if it were not for the fact that it is the politicians who will make peace. If they are allowed to exalt themselves they will get a hold over the public very dangerous to the national interests.54

Lord Esher’s advice to Philip earlier in the summer, that all would be well for Haig as long as there was success in the field, was true not just for the generals but also for the politicians. The Battle of the Somme had not produced the decisive breakthrough that Philip had hoped for, and there was concern that Britain might actually be losing the war. Northcliffe decided that Asquith had to be replaced as Prime Minister, and his papers led the calls for change at the top of government. He did this not out of support for Lloyd George, who would be the main beneficiary of this campaign, but because he believed that the Asquith government was weak and a peril to the country.

There was little trust between Lloyd George and Northcliffe, and the War Secretary regarded the press baron as ‘the mere kettledrum’ of Haig.55 Northcliffe would remain firmly in the camp of the generals, and the day after Lloyd George took up office as Prime Minister, he informed Philip Sassoon that he had ‘told the Daily Mail to telephone you every night at 8pm, whether I am in London or not’.fn15, 56

Philip was in London on a week’s leave during the political crisis and wrote to Haig with updates as Lloyd George’s new government took shape: ‘I think by now all the appointments and disappointments have been arranged … I think Derby’s is a very good appointment. Northcliffe said, “That great jellyfish is at the War Office. One good thing is that he will do everything Sir Douglas Haig tells him to do”! I think the whole week has been satisfactory.’fn16, 57

Philip also made good use of his London leave by arranging to meet the leading novelist Alice Dudeney, whose books he had long admired, having been introduced to her works by his friend Marie Belloc Lowndes. Alice Dudeney was well known for her romantic and dramatic fiction, often based on life near to her home in East Sussex, and would publish fifty novels in the course of her writing career. Philip managed to get her address from Marie, and wrote out of the blue to her: ‘I am such a great admirer of your books that I know it would be the greatest pleasure to me to talk to you. Would you not think it impertinent of me to introduce myself in this manner and to say how much I hope you may be able to come to lunch [at Park Lane].’58 Alice duly came to lunch with Philip and Sybil the following week, and it was the start of a great friendship between them that would last the rest of his life.

Throughout the war, in what spare time he had, Philip read contemporary novels, taking up suggestions from Marie Belloc Lowndes, and getting his London secretary, Mrs Beresford, to send them out to him at GHQ. The one book that he kept constantly by his side, reading it again and again, was Marcel Proust’s Du côté de chez Swann, the first volume of À la recherché du temps perdu, which had been published in 1913. The novel’s narrator opens the story by recounting how as a boy he missed out one evening on his mother’s goodnight kiss, because his parents were entertaining Mr Swann, an elegant man of Jewish origin with strong ties to society. In the absence of this kiss he gets his mother to spend the night reading to him. The narrator says that this was his only recollection of living with his family in that house, until other sensations, like the taste of a madeleine, brought back further memories of that time. For Philip, alone in his hut at GHQ, the world before the war had become a distant memory. Perhaps as he read Proust’s lines he was trying to remember his mother’s kiss, or a weekend party at Taplow with friends who now lay dead in Flanders. Even a loud cracking noise outside, like the sound of a stock whip, might be enough to bring Julian Grenfell vividly back to life.

The British entered the new year of 1917 with little confidence that the end of the war was in sight. Philip Sassoon remained steadfast in his support for Haig (who was now a field marshal) and in a well-reported public speech during a visit back to Folkestone in January he told his audience:

They could trust their army and trust their generals. For them [the generals] the days of inexperience and over-confidence were gone. They knew their task, and they knew they could do it … the Battle of the Somme had opened the eyes of Germany, and she saw defeat in front of her. We must not be trapped by any peace snare. We had the finest army our race had produced, a Commander in Chief the army trusted, and a government they believed capable of giving vigour and decided action.59

The new Prime Minister, however, had the generals in his sights. Lloyd George had formed a new government in response to growing concerns about the direction of the war, and he wanted to have some influence on the conduct of operations on the Western Front. In this regard he was determined to sideline or remove Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Haig as Commander in Chief in France.

Philip would accompany Haig to a series of conferences in Calais, London and Paris, where Lloyd George’s plan unfolded: to create a new supreme command for the Western Front that would remove power from Haig and transfer it to the French generals above him, as well as give more autonomy to the divisional commanders in the field. Lloyd George also brought Lord Northcliffe inside his tent by appointing him to represent the government in the United States of America, on a special tour to promote the war effort. Northcliffe was delighted with his new role, and the Prime Minister then felt emboldened to perform a further coup de main by bringing Churchill back into the cabinet as Minister for Munitions.

The War Secretary, Lord Derby, wrote to Philip to complain that he ‘never knew a word about [Churchill’s appointment] until I saw it in the paper and was furious at being kept in ignorance, but you can judge my surprise when I found that the war cabinet had never been told … Churchill is the great danger, because I cannot believe in his being content to simply run his own show and I am sure he will have a try to have a finger in the Admiralty and War Office pies.’60

Philip could all too clearly see the dangers of Lloyd George’s initiatives for Haig and GHQ. After the Calais conference where the Prime Minister had first set out the idea of a combined French and British supreme command, Philip warned Esher that despite the personal warmth of the politicians towards Haig, his position remained vulnerable. He wrote, ‘Everyone – the King, LG, Curzon etc. – all patted DH on the back and told him what a fine fellow he was – but with that exception, matters remained very much as Calais had left them and the future may be full of difficulties.’61

It was not just the continued heavy casualties being sustained at the front; now German bombing raids on England from aerodromes in Belgium were inflicting terrible loss of life at home as well. On 25 May 1917, on a warm, clear late afternoon, German Gotha aeroplanes dropped bombs without any warning on the civilian population in Folkestone, in Philip’s parliamentary constituency. One fell outside Stokes’s greengrocer’s in Tontine Street, killing sixty-one people, including a young mother, Florence Norris, along with her two-year-old daughter and ten-month-old son. Hundreds more were injured, and other bombs fell on the Shorncliffe military camp to the west of the town, killing eighteen soldiers. The raid shocked the nation and led to calls for proper air-raid warning systems to be put in place in towns at risk of attack.

There was further controversy over Douglas Haig’s brutal offensive in the late summer and autumn of 1917 at Passchendaele in Flanders. In June GHQ had suggested to the cabinet that 130,000 men would cover the British losses that would be sustained during the course of the battle. Instead, the total number of British casualties across the whole of the front by December was 399,000. When it became clear that no significant breakthrough had been achieved, Lloyd George resumed his agitation for Haig’s removal, but a victory at the Battle of Cambrai in late November initially seemed to secure the Commander in Chief’s position. Cambrai was the first successful use of tanks on a large scale, but there was criticism that the level of success had been exaggerated by the military intelligence staff at GHQ, and then more seriously that they had tried to cover up failings on their part which had allowed the Germans to counter-attack successfully, retaking most of the territory they had lost. Two of Philip Sassoon’s Eton and Oxford friends, Patrick Shaw Stewart and Edward Horner, lost their lives in the battle.

The outrage at the missed opportunity of Cambrai, and the further unnecessary loss of life that seemed to be a direct result of poor planning on the part of the generals, shook even Northcliffe’s belief in the military leadership. The Times reported that ‘The merest breath of criticism on any military operation is far too often dismissed as an “intrigue” against the Commander-in-chief.’ It demanded a ‘prompt, searching and complete’ inquiry into the fiasco of Cambrai.62

Lord Esher discreetly briefed Lloyd George at the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris on the full extent of what had happened at Cambrai, which produced a furious reaction from the Prime Minister. Esher recalled in his diary that Lloyd George

launched out against ‘intrigues’ against him. Philip Sassoon was the delinquent conspiring with Asquith and the press. I expressed doubt and said that Haig had no knowledge of such things if they existed, but Lloyd George replied that every one of the journalists etc. reported interviews and letters to him. He was kept informed of every move. He then used most violent language about Charteris … Haig has been misled by Charteris. He had produced arguments about German ‘morale’ etc. etc. all fallacious, culled from Charteris. The man was a public danger, and running Haig. Haig’s plans had all failed. He had promised Zeebrugge and Ostend, and then Cambrai. He had failed at a cost of 400,000 men. Now he wrote of fresh offensives and asked for men. He would get neither.63

Philip Sassoon shared the growing disillusion over the reliability of Charteris, and after being told by Esher about his meeting with the Prime Minister wrote back that he had ‘never agreed with these foolish optimistic statements which Charteris has been putting in DH’s mouth all year but what they [the war cabinet] ought to know is that morale is a fluctuating entity and there is no doubt that events in Russia and Italy have greatly raised the enemy’s spirits’.fn17, 64

Lord Derby told Haig that the war cabinet had no confidence in Charteris and wanted him to be removed from his position. He added that in his opinion practically the whole army considered Charteris to be ‘a public danger’.65 The following day Lord Northcliffe weighed in against him as well. He warned Philip Sassoon, ‘I ought to tell you frankly and plainly, as a friend of the Commander in Chief, that dissatisfaction, which easily produced a national outburst of indignation, exists in regard to the Generalship in France … Outside of the War Office I doubt whether the High Command has any supporters whatever. Sir Douglas is regarded with affection in the army, but everywhere people remark that he is surrounded by incompetents.’66 The message was duly delivered to Haig, who acknowledged that it was impossible to continue to support Charteris when he had ‘put those who ought to work in friendliness with him against him’.67 Charteris was gone the same day. Philip had little sympathy for him, telling Lord Esher that ‘rightly or wrongly he was an object of odium and his name had become a byword even at home. I hear that he has been heading a faction against me for developing the position of private secretary too much. I am diverted. I went to see DH but you know the length of my material ambitions and I would not stay on a second longer than I was wanted.’68

Haig survived the crisis, but in February 1918 Robertson was replaced as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and the following month Lloyd George achieved his aim with the creation of a supreme Allied command for the armed forces on the Western Front under the French general Ferdinand Foch.

The various Anglo-French conferences during the war also gave Philip an opportunity to broaden his own circle of contacts in Paris, and one such opportunity presented itself at the Hôtel Claridge. He was attracted to successful people from a wide range of backgrounds, although the sporting, media and cultural worlds were firm favourites. One morning during a break in the conference proceedings Philip spotted across the lobby the handsome French flying ace Georges Carpentier. As Carpentier recalled:

A slim distinguished-looking gentleman with fine features came up to me and chatted to me in excellent French though with a slight English accent … Realising that he was a member of the British delegation I took out my cigarette case and said, ‘Do you know what I’d like very much? To get the autographs of Admiral Beatty, Winston Churchill and the other gentlemen on this case.’

‘That is a perfectly simple matter,’ he replied with a smile. ‘Let me have the case and I’ll give it back to you here tomorrow. Unless you would like me to leave it at your place?’

I left it with him and arranged that I should come back to Claridge’s the next day to pick it up. My unknown friend was as good as his word and when he returned my cigarette case it bore the signatures of Admiral Beatty, Winston Churchill, Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead and Lord Montagu – and a sixth signature Philip Sassoon. ‘I took the liberty of adding my own,’ he said with a smile.69

Their chance meeting was the start of another great friendship. Like Julian Grenfell, Carpentier was a boxer, and he would go on to have considerable success as a heavyweight champion after the war. He and Philip shared a passion for flying, an activity that was exhilarating, increasingly effective as a weapon of war, but also extremely dangerous. Carpentier had won the Croix de Guerre for his war exploits as a pilot, a decoration that Sassoon, along with other members of Haig’s staff, had also received from the French commander Joseph Joffre during a visit to GHQ in 1916. Philip had not flown in combat, but used aeroplanes to travel between meetings, and marvelled that he could get from GHQ in Montreuil back to his home in Kent in just forty minutes.

It was as recently as 1909 that Louis Blériot had made the first Channel crossing in an aeroplane, and there were frequent crashes even for experienced pilots. Winston Churchill was also a great enthusiast; he would often fly out to the front from London and return to Westminster that same evening to give an update to the House of Commons based on what he had seen. He considered the air to be a ‘dangerous mistress. Once under its spell, most lovers are faithful to the end, which is not always old age.’70 In 1918, after his third plane crash, and the death of airmen in aircraft that he had previously piloted himself, Churchill gave in to the pressure from his family and friends to abandon his mistress. Philip, free from such domestic pressures, remained faithful to the air throughout his life, and not just because of its speed and convenience, but because in the skies he didn’t suffer from the motion sickness that made journeys by sea such an ordeal for him. Air travel also demonstrated just how close normal life was to the horrors of the Western Front. Folkestone was less than 100 miles from Ypres, and from his house at Lympne Philip could hear the guns during heavy artillery bombardments at the front.

Working alongside the high command gave Philip the opportunity to bring forward ideas of his own. One of these was encouraging famous artists to come and use their creative perspective to capture aspects of life at the front. He shared the idea with Northcliffe, who was excited by the prospect of these works capturing the everyday nobility and heroics of the men. Northcliffe credited himself with having conceived of it but praised Philip for making it happen. For Philip it was the perfect marriage of his military duties and his artistic instincts. He obtained permits for friends like John Singer Sargent and William Orpen to spend time in Belgium and France, with the freedom to paint whatever they chose. Sargent evoked a haunting beauty in his depiction of the ruins of the cathedral at Arras and great dignity in his tableau Gassed, which showed a line of men supporting each other after suffering the temporary blindness caused by a mustard-gas attack. In bad weather Philip fixed it for Sargent to tour the trenches in a tank, ‘looping the loop generally’.71 He also arranged for him to meet with Douglas Haig to show him some of his work, and was greatly entertained by the juxtaposition of these two strong if mildly eccentric personalities. Philip would recall that ‘Sargent cannot begin his sentences and starts them in the middle with a wave of his hand for the beginning, while Haig cannot finish his and often concludes with hand work instead of words. In consequence, the meeting between the two was quite amusing – a series of little pantomimes.’ He also remembered taking Haig to see a remarkable picture by Sargent showing a train full of men going up to the front at twilight. Haig looked at it intently for some time and then, turning to Sargent, remarked, ‘I see – one of our light railways,’ to which the artist just smiled back in response.72

William Orpen was one of the greatest portrait painters of the day; his 1916 painting of a haunted Winston Churchill after the failure of Gallipoli was Clementine’s favourite portrayal of her husband. He had also previously painted Philip Sassoon and his sister Sybil. Philip arranged for him to paint a number of the generals; in May 1917 he telephoned to invite him to paint the Chief and to come and meet him at an informal lunch at advanced HQ. Haig made a positive impression on Orpen. In the artist’s view:

Sir Douglas was a strong man, a true Northerner, well inside himself – no pose. It seemed it would be impossible to upset him, impossible to make him show any strong feeling and yet one felt he understood, knew all, and felt for all his men, and that he truly loved them; and I knew they loved him … when I started painting him he said ‘why waste your time painting me? Go and paint the men. They’re the fellows who are saving the world, and they’re getting killed every day.’73

Although Philip was increasingly confident in using his position to develop his personal networks, there was one man of growing reputation he studiously avoided – his second cousin, the decorated army officer and poet Siegfried Sassoon. Siegfried was the grandson of S. D. Sassoon, the half-brother of Philip’s grandfather. While Philip was the principal male descendant of their great-grandfather David Sassoon, and the holder of the family’s baronetcy, Siegfried’s branch had become somewhat estranged from the rest of the Sassoon clan.fn18 At that time the two cousins had never met,fn19 but they had mutual friends, including the writer Osbert Sitwell and the painter Glyn Philpot. Philip had been an early patron of Philpot’s and, as already noted, had had his portrait painted by the artist in 1914. Philpot then painted Siegfried in June 1917, after the publication of his first volume of war poems, The Old Huntsman, had brought him to public attention. This was just before his statement calling for an end to the war was read out in the House of Commons, an episode that gave him even greater notoriety. His declaration would have come to the particular attention of Philip at GHQ, as Siegfried was not just some pacifist poet, but an officer who had been awarded the Military Cross for his bravery in battle. Siegfried’s fame grew in June 1918 when a second volume of his poems, Counter-Attack, was published. Lord Esher asked Philip, ‘By the way, who is Siegfried Sassoon? Tell me, and do not forget. He is a powerful satirist. Winston knows his last volume of poems by heart, and rolls them out on every possible occasion.’74 Philip initially ignored Esher’s question but, when he wrote asking again, confirmed that Siegfried was a distant relation. Philip would have found the war poet’s work embarrassing, with its constant references to the bravery of the men, the brutality of the military commanders and the incompetence of their staff officers. One poem in particular that Churchill had committed to memory was ‘Song-Books of the War’, with its lines:

And then he’ll speak of Haig’s last drive,

Marvelling that any came alive

Out of the shambles that men built

And smashed to cleanse the world of guilt.

Yet Siegfried was just as damning of the politicians as he was of the generals, exclaiming in his poem ‘Great Men’:

You Marshals, gilt and red,

You Ministers and Princes, and Great Men,

Why can’t you keep your mouthings for the dead?

Go round the simple cemeteries; and then

Talk of our noble sacrifice and losses

To the wooden crosses.

The sacrifices had been great and the losses terrible. There was no doubt by 1918 that the world had grown weary of the war, but there was still no obvious end in sight. In early 1918 the British were instead bracing themselves for a massive German assault on their lines. The Russian Revolution of 1917 had heralded victory for the Germans on the Eastern Front, which would allow them to move large numbers of men and munitions over to France and Belgium. The United States had entered the war in support of the western Allies, but its troops were only just starting to arrive at the front. On 4 a.m. on 21 March, Operation Michael, the first phase of the great German spring offensive, or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle), was launched. Its objective was simple: to smash the British, drive them back to the sea and then force the French to surrender.

Philip and GHQ would be in the firing line of the German attack and its significance was clear to him. As he wrote to Lord Esher after the offensive had started:

This is the biggest attack in the history of warfare I would imagine. On the whole we were very satisfied with the first day. There is no doubt that they lost very heavily and we had always expected to give ground and our front line was held very lightly. We have had bad luck with the mist, because we have got the supremacy in the air, fine weather wd. have been in our favour … The situation is a very simple one. The enemy has fog, the men, and we haven’t. For two years Sir DH has been warning our friends at home of the critical condition of our manpower; but they have preferred to talk about Aleppo and indulge in mythical dreams about the Americans … We are fighting for our existence.fn20, 75

The British were being driven back, but the Germans were sustaining heavy losses. Nevertheless, when the King visited GHQ on 29 March, Philip reflected to Esher that ‘This is the ninth day of the attack. It feels like nine years. There have been times in every day when one might have thought the game was up.’76 Haig told the King of his concern that, while the British army had held up well, its position had been compromised by decisions made by the politicians. They were fighting a German army vastly superior in size with 100,000 fewer of their own men than the year before, and over a longer section of front line. This was a result of Lloyd George’s agreement that Britain would take over some sectors that had previously been held by the French. The following day Philip wrote to Esher again: ‘We have been promised 170,000 men from home of which 80,000 are leave men. The remainder will not fill our losses and then basta [i.e. ‘enough’, from the Spanish]. Nothing to fall back on. It is serious.’ 77

On the morning of 11 April, Haig was at his desk early, writing out in his own hand a special order for the day, which he gave to Philip with the instruction that it should be sent to all ranks of the British forces serving at the front. Two days earlier, the Germans had launched Operation Georgette, the second phase of the Kaiserschlacht, and there was no doubting that this was the critical moment of the war. Haig wrote:

Many amongst us now are tired. To those I would say that Victory will belong to the side which holds out the longest. The French Army is moving rapidly and in great force to our support.

There is no other course open to us but to fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end. The safety of our homes and the freedom of mankind alike depend upon the conduct of each one of us at this critical moment.

The lines held, and on 24 April the great offensive was halted by British and Australian forces in defence of Amiens. The Germans would launch a final attack in July, but essentially their forces were spent, and with the arrival of growing numbers of fresh American reinforcements, it would just be a matter of time before victory would be delivered.

Philip came down with a dose of Spanish flu in July while on leave in London, and after resting made it to his home at Lympne for the weekend, before returning to GHQ. He was fortunate to have contracted a milder form of the virus that spread across the globe in a more virulent form in the autumn and winter of 1918–19. Over 200,000 people in Britain alone would be killed by the flu that claimed the lives of 50 million around the world.

Following the summer successes against the Germans he allowed himself to start to look forward to peace. He wrote to his friend Alice Dudeney about Lympne, ‘It was lovely there. I do want to show it to you. I am on the lip of the world and gaze over the wide Pontine marshes that reflect the passing clouds like a mirror. The sea is just far enough off to be always smooth and blue.’78

At 4.20 a.m. on 8 August, having withstood all that the Germans could throw at them over the previous months, the Allies launched their own offensive. This campaign, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, commenced with the Battle of Amiens, which pushed the Germans away from their positions to the east of the town. Philip Sassoon was with Douglas Haig at advanced HQ, a train parked in the station at Wiry-au-Mont, about 40 miles west of the front line at Albert. The British broke through the lines, advancing 8 miles on what the German commander Erich Ludendorff called ‘the black day of the German army’.79 Haig told his wife, ‘Who would have believed this possible even 2 months ago? How much easier it is to attack, than to stand and await the enemy’s attack!’80 The Allied advance continued through the rest of the summer and by late September the Oberste Heeresleitung, the supreme German army council consisting of both the Chief of the General Staff Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Ludendorff, told the government that the position on the Western Front was close to collapse. On 4 October the new German Chancellor Max von Baden approached the Allies with a view to agreeing an armistice to end the war, appealing in particular for the intervention of the American President, Woodrow Wilson, to act as an honest broker. As talks between the Allies and Germany continued, Philip travelled to London with Douglas Haig later that month for discussions with the French on the terms to be offered for the armistice. He told Lady Desborough after the talks, ‘We saw Foch today, he says “peace approaches”. This would certainly be the best solution of all. If only we knew and could state our peace terms we could then calmly await the day of Germany’s acceptance of them. Meanwhile Wilson über alles is the Saxon chant. Everyone is furious, but helpless. We do the fighting – America reaps the harvest.’81

At 5 a.m. on 11 November 1918, in a railway carriage parked in the Compiègne forest, General Foch signed the armistice agreement with Germany on behalf of the Allied forces. At 11 a.m. that day, the moment the agreement came into effect, Philip was with Haig and the army commanders at Cambrai, to share in the moment of celebration. The news of the pending armistice had reached Folkestone in Philip’s constituency, no doubt with his help. Reporting on the events of 11 November the Folkestone Express noted that

There had been quite an electric feeling about the townspeople from early morning. Folkestone was one of the first towns, although not officially, acquainted of the fact that the war was at an end. Consequently in the vicinity of the Town Hall crowds began to gather as early as nine o’clock all full of the news. The townspeople were augmented by soldiers from every part of the British Empire, and representatives of practically all our gallant Allies.

In the drizzling rain of a November morning, the town’s mayor, Sir Stephen Penfold, announced the news of the armistice ‘in a voice trembling with joy and maybe with grief at the thought of those who had gone never to return … Pandemonium reigned for some minutes, for motor horns and anything that could make a noise were used for the purpose of spreading the glad tidings. The bells of the Parish church rang out their joyous song. At once flags and bunting were exhibited.’82

Philip Sassoon would have little time for rejoicing as three days after the armistice David Lloyd George called a general election for 14 December. The Prime Minister wanted an immediate mandate for the coalition government that had won the war to negotiate the peace. The Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law agreed that candidates from his party who supported the coalition should receive a joint letter of endorsement, from both himself and the Liberal leader Lloyd George. It was the first time that such an electoral pact between parties had been organized. The endorsement letters were dismissed as a ‘Coupon’ by Herbert Asquith (now leader only of a splinter group of Independent Liberals), but it proved to be a highly effective tactic. This wasn’t the only revolutionary change to be rushed through for the election. The 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote for the first time to all men over the age of twenty-one, and to some women as well. Philip Sassoon had supported votes for women when he first stood for Parliament in 1912, and this reform, so long campaigned for by the suffragettes, had finally been achieved, if not yet on a fully equal basis to men.fn21 The new Act of Parliament expanded the electorate from 7.7 million to 21.4 million; and three-quarters of these had never voted before.

The election campaign was famous for its promises that Germany would be made to pay for the war, and that there would be rewards for the people in return for their sacrifice and forbearance, most notably homes ‘fit for heroes’. Philip was still on active service with Douglas Haig at GHQ, but the Chief gave him leave to make flying visits home to campaign in his constituency. His first trip back was on Thursday 21 November, and he addressed a series of public meetings before returning to France the following Monday.

Philip was ‘enthusiastically received’ at his first election rally at a packed Folkestone town hall. Some pride was expressed by his supporters in the role he had played supporting Douglas Haig during the war. Philip, now returning to the stage of the civilian politician, set out his wholehearted support for the coalition: ‘no government’, he said, ‘but a coalition government could have won the war and I am convinced that nothing but a coalition government can secure a satisfactory peace and start the country wisely, safely and prosperously on a new path. That is why I am a coalition candidate. On some points I may not, perhaps, see eye to eye with the Prime Minister, but I leave my personal views behind.’83

This speech also demonstrated the impact of the war on Philip as a politician, and his belief that things could not just go back to the way they had been in 1914. ‘The lesson of this war’, he told his listeners, ‘is that all sections of the community are dependent on one another, and why only by unselfish desire to help the common-good can happiness come.’ It was a message that his Eton friend Charles Lister, who had died of his wounds fighting at Gallipoli, would have appreciated. Charles, who had devoted much of his time to the school’s mission to the poor in Hackney Wick, would have noted the change in Philip, from the student who seemed to care only for beautiful things to the champion of opportunity for all.

In particular, Philip focused on education, care of children and their mothers, and his belief that ‘every child born should be given a chance to become a fit and useful citizen of the Empire’. He also told his audience in the town hall that housing was ‘one of the most important questions before them. It has always been important and should have been taken up before the war.’

Even on the question of home rule for Ireland, something he had campaigned against when he first entered Parliament, the war would seem to have softened his position. The Folkestone Express reported him as stating at the meeting that

He had always held very strong views and he had not abandoned them but he realised the need of a solution which would allow Ireland to build up her industrial and political prosperity. Mr Lloyd George said he would have nothing to do with any settlement which involved the forcible coercion of Ulster and on that basis he would support any measure which would bring peace and prosperity to that much troubled land.