Читать книгу Guns Illustrated 2011 - Dan Shideler - Страница 17

ОглавлениеH&R's Forgotten Tacklebox Guns BY DAN SHIDELER

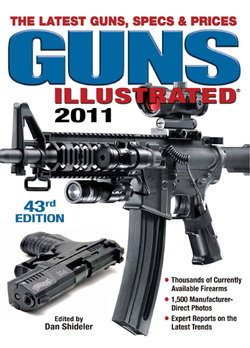

The quintessential tacklebox gun: The H&R Model 732 snubbie chambered in .32 S&W.

In the gun literature of the ‘50s and ‘60s, I find numerous references to “tacklebox guns.” That’s the kind of phrase you skate right past without giving it a second thought, but now that I’ve got you trapped there in your chair, I ask you, sir: what exactly is a tacklebox gun, anyway?

Good question. In the spirit of scien-tifi c inquiry I’ll waddle out to the garage and check my own tackleboxes.

Okay. I’ll start with this big double-hung monster labeled “TOP WATER.” After unlatching the hasps and lifting the lid, I find three Jitterbugs; two old Smithwick Devil’s Horses; 11 – wow! 11! – wood-bodied South Bend Nip-I-Didees and four smaller Spin-I-Didees; two Hed-don Crazy Crawlers; 23 Rapala Floaters, ranging from tiny #5s to mammoth #17s, several of them painfully scarred by pike teeth; and two old Fred Arbogast Hula Poppers with their skirts missing. Not bad!

And what have we here? Why, it’s a corroded bottle of Uncle Josh pork rinds, one of which has somehow escaped from its jar and welded itself to a Johnson Silver Minnow! And here’s a leaky bottle of what may have been salmon eggs. How’d they get in here? No matter. I can’t pry them loose anyway. Ewwwww.

But wait! There it is, hiding under a spool of 10-lb. Stren: a Harrington & Richardson Model 732 revolver. No doubt about it, pardner: that there’s a tacklebox gun.

What’s a gun doing in a tacklebox, anyway? Beats me. In all my fishing excursions, I’ve never had to draw down on a rogue bluegill or fend off a sex-crazed trout. Once, in northern Michigan, I did see a guy shoot a dogfi sh off his hook rather than touch it, but I personally need a tacklebox gun like I need a sixpack of Chanel #5. Once again, however, we see the yawning gulf between “need” and “want.” I may not need a tacklebox gun, but I sure do want a tacklebox gun.

Nobody makes tacklebox guns any more. Properly applied, the term refers to an inexpensive, short-barreled (4-inch maximum), solid-frame revolver with fixed sights that was chambered for .22 rimfire or .32 centerfire. H&R’s top-break models such as the justly-famous Model 999 Sportsman or the Model 925 Defender can’t really be considered tacklebox guns because their fit and finish made them much too nice to stick in a tacklebox.

A real tacklebox gun has fixed sights, usually a blade front paired with a hog-wallow groove milled into the topstrap. Some models from the 1980s have a drift-adjustable rear sight dovetailed into the topstrap, but that’s about as fancy as they get. The purpose of a tacklebox gun, as best I can fi gure, is to shoot a snake, or to defend oneself from a class of miscreant that my father loosely categorized as “Red-Headed Ridge-Runners,” or to blast open a stubborn can of Van Camp pork-‘n’-beans.

Who needs target sights? Before the war, lots of makers – H&R, Iver Johnson, Forehand & Wadsworth, Hopkins & Allen, Howard Arms and about a zillion others – made inexpensive, small-frame revolvers, but these seem to have been intended more for the coat pocket or the nightstand drawer than the tacklebox. Many such H&R revolvers were sold through the Sears, Roebuck Wish Book, priced as low as $1.75 apiece (add 20 cents for postage) and advertised as “STRICTLY FIRST CLASS IN EVERY RESPECT.” Uh huh.

The Golden Age of the Tacklebox Gun lasted from 1950 to around 1990, coinciding with the post-war boom in anything related to the outdoor sports. It was the glorious era of George Leonard Herter, Old Town Canoes, Nimrod pipe lighters, Winchester Staynless shotgun shells – and tacklebox guns.

Harrington & Richardson was the king of tacklebox gunmakers. Iver Johnson gave them a run for their money, but H&R concentrated on tacklebox guns with an admirable singleness of purpose. Today, these sturdy little revolvers are universally ignored by collectors. As a result, they’re usually dirt cheap, an attribute not without merit. In addition, they’re virtually indestructible and they go bang when you want them to, usually in the general direction they’re pointed. Most importantly, they’re not so precious that you’d be heartbroken if they ended up at the bottom of the Tippecanoe River. What’s not to like?

H&R’s tacklebox guns subdivide into two types: those with swing-out cylinders and those with removable cylinders. Both types can be fired in single-or double-action mode. The swing-out revolvers were the Cadillacs of the H&R tacklebox line, if such a thing can be said without my being sued for slander by General Motors. The cylinders of these guns lock at only one point: the spring-loaded extractor rod engages a recess in the recoil shield. And that’s it. No lug up front with an additional lock, a la Smith and Wesson; no thumb latch on the sideplate or anywhere else. To swing out the cylinder, you pull forward on the spring-loaded extractor rod and swing the cylinder out of the frame. A swift bop on the extractor head pops out all empty shells simultaneously.

H&R’s removable-cylinder tacklebox guns come in two fl avors. The first, and most common, features a removable cylinder pin. You press a spring-loaded detent on the frame, pull the cylinder pin entirely free of the gun and roll the cylinder out into your waiting hand (and hopefully not into Lake Wawasee). Then you laboriously stab out each empty case with the cylinder pin.

The second fl avor features a snap-out cylinder. In this design, the cylinder, cylinder pin and extractor are all comprised in a single assembly. Pressing the detent lets you snap out the whole works through a cut-out on the left side of the frame, after which you extract all empties simultaneously with one thrust of the extractor. Although H&R advertised their snap-out revolvers for at least 20 years, I haven’t seen more than a handful of them on the used-gun market in my life. Possibly too many cylinders snapped out permanently and now sleep with the fi shes: “Snap! Splash! Aw, *#*&*!!” It appears that the snap-out models were produced concurrently with the removable-cylinder pin models before being discontinued altogether in the mid-1960s.

H&R tacklebox guns usually incorporate two features that you wouldn’t expect to find on a price-point revolver. The first is H&R’s patented “safety rim,” a raised edge running around the rear face of the cylinder and enclosing the chambers. The safety rim was intended to protect the shooter from the effects of a case head separation, a fairly common occurrence with the rimfire ammunition of the day. (In my shooting life I’ve experienced only one case head failure, and trust me, once is enough.)

The second remarkable feature is H&R’s transfer bar safety. This feature first appeared, not on the Ruger New Model Blackhawk of the 1970s, but on pre-war Iver Johnson revolvers. Advertised under the memorable tagline “Why It’s Safe to Hammer the Hammer,” the IJ transfer bar interposed a steel wedge between the hammer and the frame-mounted firing that transferred the hammer blow to the firing pin but only if the trigger were held all the way back. I don’t know whether H&R purchased rights for the transfer bar from Iver Johnson, but most if not all H&R tacklebox guns have one nevertheless.

H&R’s “safety rim” cylinder incorporated a raised edge that enclosed the cartridge rims and offered some degree of protection against a pierced primer or case head failure.

Assembling a model-by-model chronology of H&R’s tacklebox guns is a bit difficult because some models seemingly drifted in and out of the product line willy-nilly. Features such as grip material seem to have varied according to whatever H&R had on hand. And things really got muddled during the company’s final years when it was known as H&R 1871, Inc., and New England Firearms (NEF) simultaneously.

All in all, H&R built tacklebox guns under one name or another from around 1950 to 1998. When Marlin bought the assets of H&R 1871/NEF in November of 2000, manufacture of H&R revolvers ceased altogether. Here’s a run-down of H&R’s tacklebox guns, courtesy of the 13th edition of Modern Gun Values (Krause Publications), which I had the great pleasure of editing:

SWING-OUT-CYLINDER MODELS

H&R Model 732: A bulky little six-shooter chambered in .32 S&W/.32 S&W Long. Blued finish with checkered plastic grips and a 2-1/2- or 4-inch barrel. Introduced 1958 and dropped in 1985.

H&R Model 733: Identical to the Model 732 but in chrome finish with white plastic grips.

H&R Model 900: An economy-grade nine-shooter chambered for .22 rimfire. 2-1/2-,4- and 6-inch barrels with blued finish and plastic grips. Introduced 1962 and dropped one year later.

H&R Model 901: Similar to Model 900 but with chrome finish and white plastic grips.

Model 929 Sidekick: This was H&R’s first swing-out cylinder model. Introduced in 1956, it merited mention in the editorial section of the 1956 Gun Digest, one of the very few times that august publication deigned to do so. Barrels were 2-1/2-, 4 and 6 inches. Blued finish with checkered plastic grips. Discontinued 1985.

New England Firearms Model R73: Based on the older Model 732, this was a 3-inch-barreled fi ve-shooter chambered in .32 H&R Magnum. Blue or nickel finish with hardwood grips. Introduced in 1988 and dropped in 1999. The scarcest of H&R’s tacklebox guns.

New England Firearms Model R92: The last incarnation of the Model 929. A .22 rimfire nine-shooter with blue or nickel finish and hardwood grips. Introduced in 1988 and dropped in 1999.

REMOVABLE-CYLINDER MODELS

H&R Model 532: A five-shooter chambered in .32 H&R Magnum. Blued finish with hardwood grips. Introduced 1984 and dropped one year later. A remarkably difficult gun to find.

H&R Model 622: H&R’s plain vanilla tacklebox gun. A .22 rimfire six-shooter with blued finish and plastic grips. 2-1/2-, 4- and 6-inch barrels; introduced in 1957 and dropped in 1963.

H&R Model 623: Similar to the Model 622 but in chrome finish with white plastic grips.

H&R Model 632 Guardsman: A .32 S&W Short or Long six-shooter with 2-1/2- or 4-inch barrel and blued finish with black plastic grips. Centerfire version of the Model 622. Introduced around 1950 and discontinued around 1957.

H&R Model 733 Guardsman: Similar to the Model 732 but with chrome finish and white plastic grips.

H&R Model 922: Similar to the Model 622 but with a nine-shot cylinder and 4-, 6- or 10-inch barrel (the latter being called the “Trapper Model”). Introduced as early as 1919 and reintroduced around 1950 without the 10-inch barrel option. Wood (early production) or reddish-brown or black plastic grips. Discontinued in 1985.

H&R Model 923: Similar to Model 922 but with nickel or chrome finish and black or white plastic grips (walnut on early models).

When Marlin acquired H&R 1871/New England Firearms in November of 2000, they dropped all handgun models permanently. The only lasting reminder of the tacklebox gun is, oddly enough, the .32 H&R Magnum cartridge, an excellent little number that was first chambered in H&R’s Model 532.

Most H&R tacklebox guns can be had for under $200, even in Excellent or Mint in Box condition. The few models chambered for .32 H&R Magnum may go as high as $275. At these prices, I’m tempted to buy as many of these little boogers as I can find. If I run out of places to store them, I suppose I can always buy more tackleboxes.