Читать книгу Battle Castles - Dan Snow - Страница 6

Оглавление

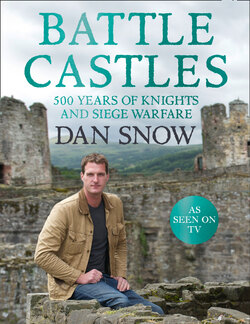

Two magnificent gatehouses at Caerphilly – one of the largest castles in Britain

INTRODUCTION: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE MEDIEVAL CASTLE

I grew up in a landscape marked by violence. We all did. I spent my childhood in Britain where, even before the bombs which fell during the Second World War, hilltop after hilltop and every town in between bore the scars of war. The memories of these older wars have long been fading. It has been centuries since hostile armies criss-crossed the English landscape, since villages were torched, and since desperate men, women and children sought refuge behind strong walls. Nevertheless, the country’s towns, cities and wider landscape were shaped – are still shaped – by a brutal past.

Family car journeys when I was a boy took us past the jagged outlines of ancient buildings. They were mostly ruins, but even in a dilapidated state, with uneven walls and collapsed towers, they captured the imagination of everyone who saw them, especially children like me. They were castles: a type of fortification so widespread and so iconic that they have come to symbolize an entire period in our history.

This is not only true of England: thousands of castles remain in every corner of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and beyond. From the mouth of Lough Foyle in the north of Ireland, to the Alborz Mountains of Iran, castles or their ruins still dominate the landscape and our imaginations. Their massive walls have survived the assaults of both the human and natural worlds, from trebuchets to earthquakes. They are a constant reminder to us today of a time when violence, or the threat of it, was the norm.

As an adult I have continued to be enthralled by these massive skeletons, or ghosts, which stand in our landscape, speaking of very different times. What are they? And what do they tell us? I recently made a television series about some of the greatest surviving castles. I travelled across Europe and the Middle East to walk their battlements, crawl through tunnels, and climb the hills on which they often stand. Built during a period of over two hundred years, from the late twelfth to the early fifteenth centuries, they have helped me to understand how the medieval castle developed during its period of greatest dominance. In different fields of conflict – from the English struggles to subdue the rebellious Welsh to the efforts by Christian kingdoms in Spain to conquer territory held by Muslims; from the Crusades by European knights in the Holy Land to the lesser-known Northern Crusade of the Teutonic Knights in Poland – an arms race took place between the builders of fortifications and the designers of attack weaponry. It oscillated one way then the other, at times evenly poised, until finally it favoured the well-equipped besieging army whose arsenal was too powerful for even the strongest castle. The age of the castle was over; but their influence continued long after in the ways we built. Many of these castles still stand, demanding to be understood.

Maiden Castle in Dorset, England, is one of Europe’s biggest Iron Age hill forts

Ira Block / Getty Images

Hadrian’s Wall was built by the Romans across a 70-mile stretch of northern Britain in the second century AD

What, then, is a castle? And how did this type of building come to exist and to play such an important role for centuries? To some extent, of course, castles speak of a universal human desire for security. Like other animals, humans have always sought to protect themselves. Even today we use bricks and mortar, wood, metal and stone to give ourselves some measure of protection from both the elements and other people. The earliest humans used the natural defences of the landscape: caves, mountain passes, rivers and swamps. Nearly 12,000 years ago Neolithic man built a massive stone wall to protect Jericho. Iron Age defensive structures – ramparts and ditches – remain clearly visible, particularly from the air. The Romans built walls, forts and camps right across their vast domain: an attempt to secure themselves against the incursions of barbarian tribes like the Saxons and the Franks.

In Britain it was the Anglo-Saxons who were the principal successors to the Romans, but they in turn came under pressure from without. Their response to the seafaring, warlike Vikings was to put their faith in fortifications. They built walls round important towns, creating defended settlements called ‘Burhs’ (Wareham and Wallingford are well-preserved examples). In France, meanwhile, the Viking onslaught prompted people to build subtly different defences. It was here that a new kind of fortress appeared on the scene: the castle.

The word ‘castle’ came from the Latin castellum, a term which simply meant any kind of fortified building or town. In English the word has come to describe the grand fortified residences of kings and lords. Most people agree that a castle was a combination of a fort, the residence of a lord and a centre of authority. However, in his excellent recent history book, The English Castle, John Goodall remarks that, ‘a castle is the residence of a lord made imposing through the architectural trappings of fortifications’. This gets round the tricky problem that many buildings that look like massive castles are actually lavish palaces; they look imposing, but are in fact militarily indefensible and not really forts at all.

Castles spread fast through a fragmented, violent Europe. In the 840s, Charles the Bald had just succeeded as King of the West Franks (a kingdom that was to morph roughly into modern France). He and his brothers were at each other’s throats as they wrestled with the problem of governing their grandfather Charlemagne’s vast legacy, which stretched from the north of modern Spain through France, Germany and Northern Italy. They faced external threats: the spread of Islam in the Iberian Peninsula; the Vikings who raided deep inland, as far as Paris several times in the ninth century. Within, they faced the perpetual aggravation of a restless and independent-minded aristocracy, eager to bolster their position by building. It was in the midst of all this, in 846, that King Charles issued a historic order: ‘We will and expressly command that whoever at this time has made castles and fortifications and enclosures without our permission shall have them demolished.’

Neuschwanstein is a nineteenth-century palace in southern Germany with a castle-like appearance, built by King Ludwig II of Bavaria

Ingmar Wesemann / Getty Images

Charles was referring to strongly-fortified residences of the aristocracy. Initially they were simply strong houses, such as Doue-la-Fontaine in Anjou which was given much thicker walls and an easily defensible entrance on the first floor. In the region which would become the kingdom of England, homes of lords were not designed to withstand a determined onslaught – the main fortifications were the burhs, communal defensive structures built by royal command. In France, by contrast, the local magnates responded to collapsing central authority by taking matters into their own hands. Government came to be exorcized by the local lords. They issued coins, collected the taxes, defined and enforced the law. Every local warlord became a king, and kings needed grand fortified residences. Political authority was becoming fragmented and the architecture of the castle was the physical manifestation. The Italian word describing this breakdown of authority is incastellamento, explicitly linking the rise of castles with the decline of central control. Castles conferred autonomy, which is exactly why rulers like Charles the Bald, desperate to re-establish royal control, wanted them destroyed.

Ultimately the attempt to destroy them was, of course, in vain. (Often, in the course of my travels round Europe, I mused on the futility of Charles the Bald’s command.) Castles were here to stay. Once Charles’ vassals had seen the strength of castle walls and felt the independence they gave them, they were loath to give them up. Too many of them had developed a taste for power. To the south-west of Paris, near Tours, the Count of Anjou Fulk III, for instance, built one of the earliest stone towers in Europe: the Château de Langeais. The tower was called a donjon, from the Latin dominium or lordship. In Spain they would become known as torre del homenaje, meaning place of homage. Both terms emphasize that these buildings were the physical demonstration of power.

In one region of modern France, meanwhile, a further change took place which saw these fortified houses evolve into what we would now recognize as castles. In the north-west corner of the country, a particular group had taken local autonomy to the point of outright independence. The Normans were the descendants of Vikings – Norsemen who had arrived as raiders and stayed as settlers. They were tolerated by the French kings as long as the Normans paid lip service to their royal authority. But while the Normans swore fealty to the Crown, they also built castles.

By the mid-tenth century strange mounds were appearing across France, and particularly in Normandy. Known as ‘mottes’, meaning turf in Norman French, they were artificial hillocks to bolster defensive structures. They would often be surrounded by a wooden stockade or ‘bailey’ with animal hides hung on them to combat the effects of fire. On the motte it was customary to find a wooden or even a stone donjon. In the first half of the eleventh century, Normandy became thick with castles. The Duke’s palace at Rouen had a mighty donjon, and another twenty-six castles – mostly built in the first half of the century – sprang up between the towns of Falaise and Caen alone. The process was described by a French chronicler:

The richest and noblest men … have a practice, in order to protect themselves from their enemies and … to subdue those weaker, of raising … an earthen mound of the greatest possible height, cutting a wide ditch around it, fortifying its upper edge with square timbers tied together as in a wall, creating towers around it and building inside a house or citadel that dominates the whole structure.

A drawing of a wooden motte-and-bailey castle. This design became commonplace in England with the arrival of the Normans

Dorling Kindersley / Getty Images

In Normandy, when Duke Robert the Magnificent died on the way to the Holy Land, his seven-year-old son, William, succeeded him. Chaos ensued. As always when political authority fragmented, castles appeared. Normandy was deeply unstable. Three of William’s guardians were killed by usurpers, one in William’s bedchamber. A Norman chronicler, William of Jumièges, wrote that at this time, ‘many of the Normans, renouncing their fealty to him, raised earthworks in many places and constructed the safest castles’. In his late teens, however, William crushed the rebels at the battle of Val-ès-Dunes in 1047. Another biographer wrote that this was ‘a happy battle indeed which in a single day brought about the collapse of so many castles’. William exploited his new power. He issued the so-called Consuetudines et Justicie in which he banned the building of castles in his domain without his consent. Importantly, he defined a castle as any building which had a motte and bailey, plus ditching, earth ramparts and palisading.

A penny struck during the reign of William the Conqueror, King of England (1066–87)

Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge / The Bridgeman Art Library

The Bayeux Tapestry – a 70-metre-long embroidered cloth record of Anglo-Norman relations in the eleventh century, culminating with the Battle of Hastings and the crowning of William the Conqueror in Westminster Abbey – gives useful depictions of several castles, particularly where it portrays William on campaign in Brittany. Three castles are shown: Dol, Rennes and Dinan. All have mottes, and they are strengthened with towers and walls. These defences seem to be made out of wood, since the soldiers are trying to set fire to them. It is clear that by the second half of the eleventh century, castles were becoming a common sight across the French landscape; and in fact they were beginning to spread abroad.

The eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry tells the story of the Norman Conquest. In this section, the process of layering soil to build a motte is depicted by the different colours in the embroidery

Musée de la Tapisserie, Bayeux, France / With special authorisation of the city of Bayeux / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Even before the Norman Conquest, kings of England like Edward the Confessor spent time in Normandy, had a Norman family and Norman advisers. In 1051 an English chronicler wrote that these Norman supporters, granted land by the King, were making themselves unpopular – and one way they did this was by building castles. In Herefordshire, he recorded, these ‘foreigners’ had built a castle, from which they ‘inflicted every possible injury and insult upon the King’s men in those parts’. The site of this castle was probably Ewyas Harold, halfway between Hereford and Abergavenny. I have stood here on a spur looking west towards the higher hills of the Welsh border. You would not think it had much significance now. No walls or battlements survive to inspire daydreams of medieval knights; there is only a tell-tale mound or ‘motte’, and the age-old tussle between goats and undergrowth. But here at Ewyas Harold the story of the English castle began: for this was probably the site of the first French-style castle built in England. Others quickly followed, and a century later there would be few corners of England without one.

Even at this early stage their purpose and impact was clear. A castle was what you built if the locals really didn’t want you there. The snippet of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is illuminating despite its brevity. Castles allowed lords to behave with impunity. From a secure base they could inflict ‘every possible injury and insult’, without fear of retaliation. They might look like defensive structures, but castles were not for cowering. They were springboards from which owners were able to dominate the surroundings, and they made the most striking claim possible about lordship in the domain.

When Edward the Confessor died childless in 1066, three men claimed to be his rightful heir. The English magnate and warlord Harold Godwinson seized the throne, and near York he annihilated the army of King Harald Sigurdsson of Norway (‘Hardrada’, as he was known: ‘hard ruler’). Then William, Duke of Normandy, landed on the south coast, and his first act, tellingly, was to build a castle.

He appears to have brought the necessary materials with him from Normandy. In the ruins of the Roman fort at Pevensey, William’s first castle quickly took shape. Days later, he marched along the coast to Hastings where he immediately set to work on a second, whose motte still stands: part of a stunning castle site which man, weather and sea have left a beautiful ruin. Standing in the ruins it is easy to imagine the trepidation that William’s men must have felt, looking down at the thin strip of ground beneath the walls: their only toehold in a hostile and warlike land.

The Bayeux Tapestry shows the building of Hastings, and gives us a vital piece of evidence for the construction process. Mottes were built in layers – a band of soil, then a band of stone or shingle, followed by another layer of soil. Baileys would have been built around the motte, while on top would have been a timber tower probably with a fighting platform or walkway. Although, unsurprisingly, none of these wooden structures survive, at Abinger in Surrey archaeologists have discovered post-holes in a motte built within a few decades of 1066. Labour would almost certainly have been provided by the unfortunate natives, forced to build buildings that were both the means and symbol of Norman imperialism. It all became too much for two workers, depicted in the tapestry having a fight with their shovels behind the supervisor’s back.

William’s two new castles were not to be tested during that late summer. King Harold of England marched south to meet this new invader, hoping that the same lightning tactics that had surprised and defeated Hardrada would also beat William. It was a mistake, but only just. In one of the longest and hardest-fought battles of medieval history, William won an attritional, bloody contest. The best guess is that the English army broke just before sunset after Harold was terribly wounded or killed by an arrow in the eye. The corpses of Harold, his brothers and the cream of the Anglo-Saxon warrior class lay mutilated on the battlefield. The throne was William’s, but he harboured few illusions that he would be widely welcomed. From Sussex he marched to Kent and took possession of the strategic fortress at Dover, the important site which guarded the narrows between Britain and mainland Europe. Its defences would be improved by William and his successors until it stood as one of the mightiest castles in the world (see Chapter 1). From here, William moved slowly towards London and briefly visited Westminster for his coronation, before heading east into Essex while a suitable castle could be built ‘against’, writes his biographer, ‘the inconstancy of the huge and savage population’.

The White Tower is the keep at the heart of the Tower of London. Built by William the Conqueror, its basic design provided a model for Henry II’s keep at Dover

photo © Neil Holmes / The Bridgeman Art Library

Faced with inhospitable locals, the invaders built castles. To control London the Normans built two, one in the west and one in the east. Soon there were three: Montfichet, near the present-day Ludgate Circus, Baynard’s Tower on the site of the modern Blackfriars, and a castle that would be forever synonymous with English kingship and royal authority, referred to simply as The Tower.

William ordered his engineers to build a castle which reflected his new-found status as king, in the south-eastern corner of the old Roman wall that surrounded the city. They started constructing a vast stone tower, one of the largest in Christendom. Nothing like it had been seen in Britain since the Romans left, over 600 years before. At the same time he began a castle in the old Roman capital at Colchester; this had a donjon which sadly has not survived as completely as the tower. The ground plan of Colchester was the largest of any great tower in Europe. Not for the last time, a king of England would build castles to claim the mantel of the Romans.

The Tower of London was a rectangle. It had extremely thick walls and turrets at the four corners. There were four storeys with the entrance on the first floor, accessed by a wooden walkway that could be removed in war. It was divided in two by a spine so that even if half of the donjon fell, the other half could still act as a final stronghold. The rooms inside were palatial. It appears to have been heavily influenced by castles on the continent. Ivry-la-Bataille in Normandy took the same general form, and it is tempting to think that the blueprint for all these eleventh-century great towers might have been the massive ducal palace in Rouen, demolished in the thirteenth century. Much of the facing stone for The Tower comes from quarries in Normandy, the rubble fill is ultra-hard Kentish ragstone. It was a huge project and William would not live to see it completed.

William’s attitude to his new subjects only hardened as he grew to know them. Initially he seems to have hoped he could rule through the existing elite. But this uncharacteristic compassion was not rewarded by loyalty. Rebellions broke out with infuriating regularity in the years after the Conquest. From the south-west to the north-eastern tip of his new kingdom he was forced to fight vicious campaigns to secure his new domain. In addition, opportunist neighbours – Irish, Welsh, Scots and Vikings – could be relied upon to raid and harry frontier lands.

Clifford’s Tower, York. The remains we see today are thirteenth century, but the site was once topped by an earlier fortification built by William the Conqueror

© incamerastock / Alamy

Typically, William would crush the rebellion in person and then build castles to ensure a strong Norman presence right across the kingdom. These would be garrisoned by reliable allies, often relatives, who were expected to keep the peace and were allowed to enrich themselves in return. William’s biographer tells how, ‘in castles he placed capable custodians, brought over from France, in whose loyalty no less than ability he trusted, together with large numbers of horse and foot. He distributed fiefs (or landholdings) among them, in return for which they would willingly undertake hardships and dangers.’

First William had to march south-west to Exeter, where he erected a castle in the remains of the Anglo-Saxon burh. The following year he marched north through the east Midlands and East Anglia, planting castles at Warwick, Cambridge and York, among other places. Perhaps the most serious challenge came in 1069 when Edgar, the Anglo-Saxon with the best claim to the throne, invaded northern England, killed William’s lieutenant in the north and captured York, England’s second city. William sent an army north which defeated the rebels, forced Edgar into exile and punished the region heavily, salting the land to make it infertile and slaughtering inhabitants. As land and power was stripped from the English lords and churchmen who William could not trust, a small group of foreigners took over almost the entire national wealth.

Such a heist would have been impossible without castles. William continued building them at strategic points in the kingdom. He created an entire system of land ownership and obligation aimed at supporting the castle, seen as the bedrock of his regime. Land was given to knights, who in return had to serve as garrison for the nearby castle. Even tradesmen like cooks and carpenters were given places to live in return for service. On the south coast, six castles – Hastings, Pevensey, Lewes, Bramber, Arundel and Chichester – were established with a vast hinterland geared up to support them. The Welsh borders were parcelled out, as was the far north of England. Just as the Romans had fortified the coast, so too did the Normans. Whereas the Romans paid for their forts with a sophisticated central treasury and a standing army that served from province to province, Norman castles were designed to be self-sufficient. The local lord and his warriors were rooted to the land, paid not by a distant exchequer, but by the proceeds of what they could grow or acquire locally.

The power of local Norman lords meant William was not alone in building castles. An explosion in castle building followed his accession. Almost one hundred are referred to in sources before 1100, but there were many more. Across England and parts of Wales numerous surviving earthworks date from this time: 85 in Shropshire, another 36 in what used to be Montgomeryshire. John Goodall estimates that as many as 500 could have been founded in the decade after 1066 alone – some built by the king, others by the great magnates who now dominated England, and others still by relatively minor gentry, given parcels of land in reward for loyal service, their names now lost to history. This was a militarized landscape. In the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the king and his warlords built castles ‘far and wide throughout the country, and distressed the wretched folk, and always after that it grew worse’. Often mottes were sited in positions of mutual visibility, no more than a day’s march apart, so one garrison could reinforce another that found itself under attack. Visiting these ghostly mounds today, their size much-reduced by 900 years of erosion, one should imagine the three- or four-storey towers which stood on top of them, dwarfing the small dwellings nearby, and think of the wood, earth and stone with which the Normans locked down the country.

The most powerful castle builder in the kingdom, apart from William, was his relative and childhood friend William FitzOsbern, who was given a huge swathe of land from the south coast of England up to the Welsh borders. The various Welsh peoples had maintained an ancient enmity with the Anglo-Saxons which their Norman successors now inherited. Using the river network as modern humans would use roads and rail, FitzOsbern built castles, large and small, across the shifting frontier zone at places like Berkeley, Wigmore, Clifford and Monmouth. He is remembered for the stunning castle at Chepstow, sitting proud on towering cliffs, dominating the sweeping bend of the River Wye. To visit it today is to feel like you are entering a royal palace, and it may in fact have been just that. When FitzOsbern was killed on campaign in Flanders in 1071, the site reverted to King William, and it may have been William who built a palatial fortress on his Welsh border. Tellingly, it is built on the Welsh side, sending the lords of Gwent an unambiguous signal. As in Colchester or London, further clues into the Norman mindset are built into the fabric of the castle. A crumbling Roman fort nearby was looted for bricks, which were incorporated into the walls. William was embracing physically and symbolically the Roman imperial legacy. He was a new Caesar, locking barbaric Britain into a civilized empire. A new imperial project was born, and castles were its symbol.

The shell-keep of Arundel Castle which was built in the twelfth century. The design is of the motte-and-bailey type, but the masonry used is much stronger and more durable than timber

His Grace The Duke of Norfolk, Arundel Castle / The Bridgeman Art Library

What these castles did was make it possible for around 7,000 men to pacify a country of two million people: they were the most efficient ‘force multiplier’ available in this period. This, it has always struck me, was the true reason behind their sudden supremacy. Castles burst onto the scene in medieval Europe not as expressions of strength but of weakness. They were the tool of small-scale imperial powers, such as William’s Normans, who commanded only relatively minor forces. When the Romans invaded Britain 1,000 years earlier, they did so with some 20,000 legionaries and a similar number of auxiliary troops – a massive army which was much larger than the numbers at William’s disposal. While the Romans were able to find and annihilate in battle every British army that gathered against them, William’s forces needed castle walls to shelter them from the English weight of numbers. The sources are full of accounts of Normans hunkering down and simply waiting for rebellions to subside, before sallying out to hunt down the ringleaders and punish the population. The most balanced account of the Conquest is the Ecclesiastical History written by the monk Oderic Vitalis, who had a Norman father and an English mother. His assessment of how the Normans annexed what had been the most powerful state in Western Europe was simple: ‘The king rode to all remote parts of his kingdom and fortified strategic sites against enemy attacks. For the fortifications called castles by the Normans were scarcely known in the English provinces, and so the English – in spite of their courage and love of fighting – could put up only a weak resistance to their enemies.’

Pevensey was one of the first sites to be fortified when William the Conqueror came to England. Under the Normans it was updated to include a stone keep

Robert Harding World Imagery / Getty Images

Rarely in history has an annexation proved so enduring. The Norman grip on England held strong and Norman influence and power slowly spread, with varying success, through Wales, Scotland and Ireland. By the twelfth century, one chronicler referred to castles as ‘the bones of the kingdom’. But the warlords with their mighty castles that underpinned this dominance brought their own problems. Castles had begun as a response to the breakdown of central control, and a lord in his castle was a king in his own domain. To live in a castle bred, and still breeds, an independence of spirit, a suspicion of distant rulers or central government. Conquest and occupation was led by an active warrior king, but it was often enforced by a patchwork of local, autonomous warlords. To a king of William’s stature this was not a problem, but to his successors, castles, and the men who guarded them, would often prove less like bones that gave kingdoms their integrity, and more like rocks on which the ship of state could founder.

William’s descendants would learn that castles were loyal only to the men who held the key to their gate. His son, William II, was immediately faced with a rebellion by his father’s greatest nobles, who preferred the prospect of his brother’s rule. He was forced to conduct a gruelling siege of Pevensey Castle, once the symbol of his family’s claim to the English throne, as well as sieges of other castles, before a mixture of generous promises and the non-appearance of his brother’s army allowed him to secure the throne. Castles were the weapons of occupation, but not the tools of orderly royal rule.

Across Europe similar trends were seen. As the principalities of Western Christendom chipped away at the ring of pagans and Muslims that surrounded them, they built castles on their expanding frontier zones. Against the English, William the Conqueror had believed himself to be on a Crusade, carrying the Pope’s banner into battle. The Pope encouraged this, knowing that the English Church was frustratingly insubordinate. In Iberia, the Baltic and Eastern Europe, relatively small Crusader forces would annex land and then lock it down with a network of castles exactly as William had done in Britain. The Christian toehold in the north of the Iberian peninsula, initially part of the Frankish kingdom, first broke away from French control and then became a base for the conquest or ‘reconquest’ of the rest of modern Spain and Portugal. In Catalonia, in the far north-east, the massive castle of Cardona and the magical Quermançó Castle, built in the late eleventh century on a dizzying rocky outcrop, are testament to a refusal to be dominated by their neighbours – Christian or Muslim. Further south, the sprawling central area that would become the Kingdom of Castile was so defined by castle building that its very name was derived from them. Desperate to cling onto their gains, Crusaders built castles relentlessly – and their Muslim opponents did too. At Málaga, on the peninsula’s southern coast, the great castle of Gibralfaro – clinging to a hill above the town – would prove one of the last bastions of resistance against the resurgent Christian armies (see Chapter 6).

Other Christian Crusaders pushed north and east. The warlike Normans travelled widely, building castles as they went. As William was crossing the Channel, his countrymen travelled also to southern Italy, first, it seems, as religious tourists, then as land-hungry warriors. Men like William de Hauteville, who won the nickname ‘Iron Arm’, arrived as adventurers and died as sovereigns. His half-brother Robert invaded Sicily and built San Marco d’Alunzio, the first Norman castle there, before capturing Rome itself.

Margat Castle’s black walls contrast starkly with the white limestone of Krak. Built of hard basalt, it was one of the Knights Hospitallers’ most important strongholds

In November 1095 Pope Urban II proposed a military expedition to ‘recover’ Jerusalem, the holiest site in the Christian faith – a call which unleashed wars of terrible ferocity across Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Kingdoms and principalities were carved out, besieged, captured and recaptured. In what was already a heavily-fortified landscape, the Christians built the most perfect castles in the world: Kerak, Krak des Chevaliers, Marqab and Saone to name a few (see Chapter 3). To visit them today is a truly awesome experience. At Saone, now known as Salah Ed-Din’s (Saladin’s) Castle after the Egyptian military genius who eventually captured it, there is a 30-metre-deep ditch cut into the rock either by the Crusaders or their predecessors, guarded by a monumental Crusader bastion with walls 5 metres thick. As I approached these castles, panting in the heat, the walls seemed to grow ever more formidable. I was overwhelmed by the lengths to which the Crusaders went to protect their conquered territory. But I also could not help thinking that these vast edifices bear witness to the fury and vigour with which the Muslims tried to drive them back into the sea.

With a supply chain stretching over thousands of miles, a hostile unfamiliar climate and a dizzying array of enemies close by, these castles were needed as ‘force multipliers’ more than anywhere else. Despite the utterly different terrain, they were doing the same job as castles everywhere else I had visited. A group of armed outsiders, invaders, surrounded by hostile territory, sought refuge and strength behind stone walls, gatehouses and towers. The process was universal. I saw the same thing in Syria that I had in Wales, France and Spain.

In the West, war and anarchy continued to promote the building of castles. When King Henry I of England dared to die without a male heir, despite having fathered over twenty acknowledged illegitimate children, England was again plunged into chaos. Camps formed around his daughter Matilda and her cousin Stephen. War followed. Local lords looked to their own defence. Fortifications were raised. ‘Christ and all his saints were asleep,’ a chronicler observed, and ‘the land was filled with castles’.

Castles appear to have made civil war all the more intractable. Neither side had the resources to besiege their enemy’s castles one after the other and so two competing weak regimes were eclipsed in the provinces by local powerbases. For the first time in British history, sieges really came to the fore. During a siege of Newbury Castle, Stephen demanded the surrender of the garrison and said if they held out he would hang the son of their defiant leader in broad view. The warlord defied this threat: ‘I still have the hammer and the anvil,’ he declared, ‘with which to forge still more and better sons!’ Fortunately for the child, and fortunately for England, Stephen did not carry out his threat. The boy, William, would grow up to become the supreme English knight of medieval history, the Marshal of England and saviour of the kingdom at its lowest ebb. Matilda herself was no less lucky if folklore is to be believed. Twice she escaped from being besieged, once across the frozen Thames in winter in a white cloak, and once as a corpse being taken out for burial.

The so-called ‘Anarchy’ came to an end when Matilda’s son Henry Plantagenet invaded England from France in 1153, and forced the ageing Stephen to negotiate. The death of Stephen’s heir opened the door to a deal and Stephen named Henry as his successor. Through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II would control a vast empire from the borders of Scotland to the Pyrenees. To secure it he tore down troublesome castles and built mighty royal ones, like that at Dover which rose above the white cliffs and which would endure the attacks of Prince Louis, another claimant to the throne of England (see Chapter 1).

Henry spent vast amounts of money on his royal castles. It was not unusual for half the annual royal budget to be spent either on building new castles or repairing old ones. An eyewitness observed of the building work at the Tower of London that ‘with so many smiths, carpenters and other workmen, working so vehemently with bustle and noise […] a man could hardly hear the one next to him speak’. Under Henry we know that an unskilled labourer moving earth and stones on a site like this would have been paid a penny a day. For the King these castles were about prestige as much as security. Dover was a glittering adornment to the channel coast, visible to ships passing through the narrows, a symbol of Henry’s massive empire. It was also one of many seats of government. Medieval kingship was peripatetic: kings and courts moved constantly. Since rule was personal it was wise for a king to show himself to his subjects, dispense justice and redress grievance as widely as possible. But logistics also played a part. The King and his court soon consumed all the supplies in one castle and it was easier to move to the food than to bring the food to them. Henry would have recognized the description of medieval kingship offered by his namesake, Henry IV, King of France: ‘I rule with my weapon in my hand and my arse in the saddle.’ His royal castles really were residences for him and his court on these huge progresses and they were appointed with all the finery demanded by the royal court.

The castles also served their most obvious purpose. When Scottish King William the Lion invaded England in 1173, he marched on Newcastle but did not even attempt to besiege the castle because he lacked the necessary, cumbersome siege engines. When he tried to besiege Alnwick, he was captured by English knights and eventually forced to sign a humiliating submission to the English Crown. Henry’s castles defended his northern frontier while he focussed his attention on unrest in other parts of his empire.

That empire grew wider: Ireland was sucked into the orbit of the Plantagenet Crown when Henry himself invaded and captured Dublin, and received the submission of its bishops and kings. Castles like Kilkenny, Killeen and Dunsany were planted by Henry’s subordinates, and his son, John, started work on Dublin Castle, a building that was to remain the seat of English and then British rule in Ireland until 1922. Ireland remained largely beyond the writ of English government, however, as other targets distracted English kings. It was never fully annexed, the chronicler Gerald Cambrensis lamented, because of the failure to build castles ‘from sea to sea’.

Henry’s sons utterly failed to guard their vast inheritance. Richard was a warrior, but no ruler, and John may have been a ruler, but he was no warrior. Richard died while pressing home the siege of a castle in France. His younger brother John’s reign saw Philip of France pushing to expand his kingdom at the expense of Plantagenet lands – laying siege, most notably, to Château Gaillard, the extraordinary castle Richard had built above the small town of Andely, on a bend of the River Seine (see Chapter 2). Failure and losses in France led to unrest in England itself, where rebels tried vainly to hold out in Rochester Castle (‘Living memory,’ a chronicler wrote, ‘does not recall a siege so fiercely pressed, and so staunchly resisted’). The French intervened in this English civil war and the loyal knight Hubert de Burgh led King John’s garrison at Dover in defiance of Prince Louis’ invading army (see Chapter 1).

The years following the death of Henry II witnessed a protracted struggle about the nature and limits of kingship, and castles were the physical manifestation of an aristocracy that felt themselves more than simple subjects. John, his son Henry III and even Henry’s warrior son, Edward, were no strangers to being besieged and even captured by rebels. Eventually the monarchy, in the person of Edward I, emerged victorious, but only after he had promised to abide by the restrictions placed on his grandfather and father by the Great Charter or Magna Carta.

Edward’s peace within England lasted long enough to turn his attention to unfinished business in the rest of the British Isles. Edward fought several campaigns in Wales, initially punitive but eventually of outright conquest. As always, castles were to be the method of subjugation. Edward spent a staggering £80,000 in twenty-five years, considerably more than his father had spent on the magnificent Westminster Abbey. Edward’s engineers built castles that are regarded around the world as some of the finest ever built, including Harlech, Caernarfon, Beaumaris and Conwy – a ring of steel around the recently-independent mountain region of Gwynedd in north-west Wales. To this day, a castle like Conwy dominates its surroundings. Caernarfon was built on a site with powerful Roman associations, and in its architecture and brickwork it deliberately echoed this earlier empire. This was Edward staking his claim to be the modern incarnation of the Caesars, just as his ancestor William had done centuries before. The Welsh understood the message, and when they rose in rebellion, it was these castles – symbols of hated English rule – that were a prime target (see Chapter 4). King Edward attempted to bring Scotland and Wales under the English Crown and yet again castles were used to enforce occupation. Scotland already had a wide network of castles built by Anglo-Norman settlers who had integrated themselves at the Scottish court through marriage and service to the Scottish Crown. These castles Edward sought to control as his forces dealt with widespread rebellions across the countryside led by William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. The Bruce knew just how important these castles were and rarely lost a chance to ‘slight’ or render them defenceless by collapsing an important section of wall. Scotland was never truly pacified by Edward, who died on his way north to deal with the latest of the Bruce’s victories.

As the chapters in this book explain, the design for these castles had evolved greatly since the arrival of the Normans in England. The key defence was no longer, as at Dover, a central keep, but the outer layers. Towering walls, lofty round towers and a massive gatehouse were in vogue, allowing the interior to be laid out with palatial magnificence. The gateway had always been a weak point, but by the thirteenth century changes had made it almost the strongest point of the castle. Round towers on either side in castles like Framlingham in Suffolk or Caerphilly in South Wales were pushed forward with embrasures, allowing the defenders to rake the entrance with crossbow bolts and arrows. Above the gate murder holes and ‘machicolations’ could be used to pour boiling water or incendiaries on the attackers below. Some castles were given a barbican or additional defensive layer in front of the gates, which might be offset to prevent an attacking force using a battering ram.

Scotland eventually secured independence thanks to a crushing victory at Bannockburn in 1314 in the shadow of Stirling Castle, held by the English, besieged by the Scots, and the key to central Scotland. Castles played a huge role in the nature of Scottish kingship thereafter. A geographically-disjointed state with a poor central treasury, Scotland had little choice but to delegate political authority. Lords ruled isolated areas with the powers of kings. Castles were the choice of these aristocrats, partly because Scotland was occasionally torn by civil strife (although it does not seem to have been endemic as was once thought), but partly also because of fashion. The Bruces, the Comyns, the Balliols all had Anglo-Norman blood, owned land in England, and employed the same architects and engineers as their peers had south of the border. Their castles reflected their status as demi-kings: in their own lands dispensers of justice, collectors of revenue and protectors.

Further north the kings of the Scots pursued their own imperial project, with the same vigour with which they defended their independence from the English. James IV fought long and hard to bring north-west Scotland under the control of Edinburgh. One of the most iconic castles in Britain, Urquhart, teetering on the edge of Loch Ness, was strategically vital and constantly changed hands between the Scottish Crown and the Lords of the Isles who dominated the north and west highlands of modern Scotland.

Eastern Europe, meanwhile, became a giant frontier between Christendom and the pagan, often nomadic, tribes of the steppes. The ‘Teutonic Knights’ who began operating in the Crusader States of the Holy Land pursued God’s enemies instead in the north-east of the continent, helping to convert (and conquer) Prussia on the Baltic coast. Behind them they left towering castles in red brick – strongholds like Malbork, which allowed them to dominate the region and to grow rich off its trade (see Chapter 5). The German brickmakers and engineers that they used were some of the most proficient in Europe, and further west, in Germany itself, it was said that there was a castle to every square mile, helping to frustrate the ambitions of anyone who sought to unify the hundreds of autonomous statelets, bishoprics, margravates, duchies, and the like which covered central Europe in a bewildering patchwork.

By the time Malbork came under siege in 1410, a new technology had emerged which radically changed the way castles were built, and attacked. Gunpowder, invented in China around the ninth century, gradually spread west. By the late fourteenth century it was used widely in Europe. In 1453 the Hundred Years’ War was brought to a successful conclusion by the French at the battle of Castillon, the first pitch battle in European history in which cannon played a decisive role. Weapons now existed which could pound even the mightiest walls into dust: a development which in turn triggered a series of changes in government, society and fashion, and which led eventually to the eclipse of castles.

As improvements were made to gunpowder itself, and to the weapons it powered, artillery became ever more dominant. It was also, however, vastly expensive. Effectively, only those with access to the public purse could afford to use cannon, which became the weapon of kings. This significantly undermined the autonomy of the provincial aristocracy. No longer were they free to act as petty kings behind impenetrable walls. During the civil war in England in the fifteenth century, known as the ‘War of the Roses’, even the greatest castles in the land were eventually battered into submission. Bamburgh, which had been thought to be impregnable, fell when two cannon named ‘Newcastle’ and ‘London’ smashed a breech in its walls in 1464. Dunstaburgh, Alnwick and even Harlech all fell, though Harlech had held for seven years.

The middle and inner wards of Caerphilly Castle in south Wales which was not a royal project, despite its size. The leaning tower (centre-left) was a product of damage during the English Civil War

Bolstered by the power of gunpowder, the nature of central government changed in Western European kingdoms like England, Scotland, France and Spain. The Crown has less need for a military elite, with private armies ready at an instant to march against enemies domestic or external. Instead, the ability to tax their subjects to pay for musketeers, artillerymen or ships carrying heavy guns became paramount. Strong regimes emerged which showed a determination to gain a monopoly on the use of military power. Courtiers, administrators and lawyers were required, not warlords. The court travelled less as government grew more complex and immobile. The elite came to the court, not the other way round. Courtiers built comfortable houses and palaces using sophisticated new building techniques and materials like glass which were more enjoyable to inhabit and also embodied their status within a modern political system.

Castles survived. Many people continued to regard crenellations and fortifications (however fake) as the hallmarks of aristocracy. A few people even continued to build them, but these modern castles were subtly different from their stark Norman predecessors. A castle like Bodiam in Sussex was built as a stately home in the architectural style of a castle, but with its shallow, easily drainable moat and its windows in the curtain wall it would not have withstood a siege. Edward III spent a vast amount of money on Windsor Castle in the mid-fourteenth century, none of it on improving its defences. Instead he built palatial accommodation for himself and his queen and a set of buildings in the lower bailey for his new Order of the Garter. His son John of Gaunt entirely rebuilt Kenilworth Castle with comfort uppermost in his mind and Carew Castle saw its powerful defences hobbled by the renovations of its owner at the end of the fifteenth century.

In Scotland, the Stuart dynasty slowly eroded the power of the local elites. King James II was a great fan of artillery. He reduced several castles and increased the power of the Crown before being killed by an artillery piece exploding next to him at the siege of Roxburgh in 1460. Buildings were still built that look like castles – such as Borthwick, south-east of Edinburgh – but in reality they were indefensible. (Borthwick has beautiful machicolations but no crenellations, so anyone actually trying to use them to defend the castle would be exposed to the enemy below.)

Osaka Castle was raised in the sixteenth century. The siege in 1614–15 is considered by many to be one of the most important events in Japan’s history

Jose Fuste Raga / Getty Images

In Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, who completed the Reconquista or removal of Islamic rule from Iberia in 1492, ordered all the castles in the realm to be handed over to royal control. Although this was only partially enforced, they did order the destruction of many of them. There could be no more tangible a symbol of the assertion of royal, central control over the periphery.

The process was not irreversible, of course, nor was it universal. Far-away Japan saw a surge in castle building during the anarchic Sengoku period which lasted for around 150 years from the mid-fifteenth century onwards. From this maelstrom of violence a very similar military caste to that in the West came to dominate Japan. Showing a remarkable synchronicity, they chose castles as the totems of their power. It was centuries before central government was able to assert itself fully. The capture and destruction of Osaka Castle in 1868 was a hugely symbolic end to the period of rule by the military elite and a resurgent central government confiscated thousands of castles, destroying around 2,000 of them.

The British Isles would also see one more rush to fortify as its three component kingdoms descended into a bitter, unanticipated civil war in the seventeenth century. Old castles were suddenly reoccupied and modern earthworks were added. Taking the lead from Italy, fortifications were built with a low profile and arrow-shaped bastions projecting from the walls denying enemy cannon a clear shot at a towering wall. Huge earth ramparts were erected to deflect cannon balls, and complex geometric shapes were adopted to maximize fields of fire of the defenders. King Charles I’s followers fought supporters of Parliament in a drawn-out conflict as these new strongholds sprang up across Britain. With modern improvements to their defences, many medieval castles proved a match for the ad hoc artillery trains of the Parliamentarian forces. Castles like Basing House, Raglan and Pontefract proved a serious obstacle to final Parliamentarian victory. As a result the new Commonwealth regime that succeeded the deposed and executed King Charles ordered the destruction or ‘slighting’ (weakening) of some of the finest castles of the medieval world. Pontefract was wiped off the face of the earth, Nottingham and Montgomery were destroyed. Corfe, Caerphilly and Kenilworth were slighted. Thankfully castles deemed important for coastal defence were left standing. Dover, Arundel and Rochester are evidence of the new regime’s fear of foreign intervention.

Dan Snow filming on location at the mighty Krak des Chevaliers in Syria

As I have toured the world looking at some of the most powerful castles ever built, I have been struck by the fact that, eventually even the most perfect castle will fall to its enemy. As the axe fell on the neck of King Charles in Whitehall in January 1649, the defenders of Pontefract Castle were still holding out for the royalist cause. When the news of his death reached them, the defenders negotiated a surrender. Castles can delay or grind an attacker’s force down and they can bolster a cause, but when that cause totally disappears, even the garrison of the greatest castle must submit to the inevitable. Castles may appear to sit, eternal and unshakeable above the fray, but in fact their survival and that of their garrisons depends ultimately on the wider strategic situation.

Following the war, a new, highly centralized unitary regime sought to bind Britain together as one nation and it was highly significant that they focussed on castles as representing the greatest physical obstacle to this process. Castles were seen, correctly, as the symptom of a political system dominated by an autonomous warrior elite. From now on, even after the restoration of the monarchy and Stuart family, defence would now be left to the State. The Crown built coastal forts and barracks for a national army while the vast majority of aristocrats lived in comfortable modern buildings rather than expensive, dingy, old castles.

In Western Europe gunpowder, government and fashion brought the era of classic castles with towering battlements to an end. But in many ways their story continues to this day. Man still fortifies. The massive forts in France and Belgium that stalled the Germans in World War One, the Atlantic Wall built by the Germans to protect the coast of Europe from the allies in World War Two, the contemporary walls around Israeli settlements, and the compound at Sangin in Helmand with its Hesco ramparts today, are all born of the same basic urges that drove early man to build the walls of Jericho. These defences, like castles, are force multipliers, they do the job of countless men; they provide a secure base from which to conduct combat operations and prevent an area falling into enemy hands. Perhaps we will never truly see the end of the castle.

What follows are chapters which feature the six mighty castles that I encountered during the production of the TV series Battle Castle. The contributors to the chapters in the book are leading authorities on each of the castles. Every chapter tells the story not only of the castle in question, its construction and character, but of the historical context behind its creation. Perhaps most importantly of all, each castle was tested in a terrible siege, the result of which would have a very real impact on subsequent history. These are some of the pivotal moments of history seen through the lens of a castle, and the battle for its control.

Hesco fortifications are pop-up containers into which materials such as sand or stone can be poured. The ones shown here protect a Dutch military base in Afghanistan

© Picture Contact BV / Alamy