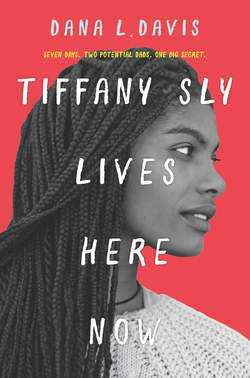

Читать книгу Tiffany Sly Lives Here Now - Dana Davis L. - Страница 11

Оглавление4

He’s here. Omigosh, he’s here. My hands are trembling as I swipe across my phone and scroll through my favorites list. I press the icon for Keelah Bo Beelah.

“Thank you for calling the Center for Disease Control. What horrible disease do you think you’ve contracted?”

“Akeelah!” I whisper. “Help me.”

“Why you whisperin’? Your new dad lock you in the basement?”

“I’m in my closet. I’m hiding.” I nervously flip my braids over my shoulder and yank on them.

“Weird. Did you forget to take your anxiety medication today or something?”

“No. I took it.”

“Then why you hiding in the closet?”

“I’m scared. Talk me through this. He’s home. He’s downstairs. I can hear him with the other kids. I hear him!”

“What other kids?”

“I have siblings. I think.”

“The fuck? What do you mean, you think?”

“Keelah. Help me out of the closet!”

“Girls or boys?”

“Four girls.”

“Dang! How come nobody told you that you had sisters?”

“Keelah, focus!”

“But I’m sayin’. Four sisters and nobody told you? That’s so lame.”

“Keelah! I’m crouched in a closet hiding from this man! Help me.”

“Oh! Okay, I got something that can help. Remember that episode of Maury Povich where the girl thought her baby-daddy was between her cousin, her boyfriend’s brother and her boyfriend? And remember how happy the boyfriend was when he found out the baby was his?”

“Are you serious?”

“Yes, girl! I love that one. That’s how happy your dad is gonna be when he sees you for the first time. He’s gonna be like that baby-daddy. He danced all over the stage and did a backflip.”

Unless he’s not the father. And suddenly all I can picture is the episode of Maury Povich I remember very clearly. Not the one Keelah’s talking about. In this one, Maury opened up a manila envelope and said, “Lula-Mae. Jim Bob is not the father.” And then Lula-Mae fell on the floor and started crying and Jim Bob screamed, “Fuck all y’all!” and ran off the stage.

“Keelah, I’m hanging up now.”

“Wait!” Akeelah exclaims. “What do your sisters look like?”

“They’re mixed.”

“Mixed? With what?”

“White.”

“Does that mean you have a white stepmom?”

“I guess so.”

There’s a long pause.

“Hello?” I whisper.

“Sorry. I’m, like, trippin’. White stepmom? What if she hates black people?”

“She has black kids!”

“Half. Not the same thing. You’re all black. She might hate fully black people. She might Cinderella you, Tiff. Be careful. You’ll be sleeping in the attic with the rats.”

“Her husband’s all black! Uggh. You’re not helping. I’m hanging up on you!”

And I do, angrily tossing the phone into the opposite corner of the closet. I scratch my back. This stupid Anthropologie dress is making me itch like crazy. I do not like Anthropologie. I look like Suri Cruise in this getup. I almost passed out cold when I saw the price tag Margaret must’ve mistakenly left on it. Four hundred and fifty dollars. For one dress?

I hear a knock coming from the bedroom. I stand, smooth out my study-of-humans dress and push through the closet door and back into the Pottery Barn room. Another soft knock and I’m stuck in an Edgar Allan Poe poem with someone faintly tap-tap-tapping gently at my chamber door. ’Tis maybe my dad and nothing more.

I clear my throat. “Come in.”

The door opens and suddenly he’s here. He doesn’t do a backflip or anything. He only stands there looking at me. He’s really tall and thin but sadly the similarities between us end there. He’s light-skinned. And the eyes. Fuck my life, for real. They’re blue.

“Tiffany Sly. You look so much like your mom. It’s as if I’ve gone back in time.”

I barely hear him. I’m too busy looking at his hair. It’s cut short but the texture looks soft and wavy. It couldn’t be possible, could it? He’s mixed?

He moves into the room and sits uncomfortably on the edge of the bed. “Tiffany, I owe you an apology.”

I can’t even muster up a sound. I can only manage to stand, frozen in place, staring at this man that I’m most certain is definitely, probably, maybe not my real dad.

“When your mother contacted me and told me she was sick, that was the first time she told me about you. I should’ve flown to Chicago right then to meet you.”

I’ve still got nothing. Still standing as frozen as an ice sculpture.

“But she made me promise. She had a plan, I suppose. Told me to go through with DNA testing but I didn’t want you to endure the stress of that process. I didn’t think it was fair. I know you’re mine. I don’t need some DNA test to prove that.”

“She asked you to take a DNA test?” So did Mom know? Is there really a possibility Anthony Stone is not my real father?

He nods. “Sometimes you know things. The heart doesn’t lie. I knew. I know. Jehovah knows I know.”

I raise an eyebrow. Jehovah?

“Right away I hired a lawyer. Right away I started making arrangements for you to be here with us after your mom passed away. It was what she wanted. It was what I wanted, too. And so here we are.”

“Yes.” I look down at the floor. “Here we are.” Then I cover my face with my hands and burst into tears.

“Please don’t cry, Tiffany,” Anthony begs. He stands and pulls me toward the bed and we sit side by side.

I wipe my eyes and runny nose with the back of my hand. Feeling so snotty and gross next to my statuesque-looking possible father. Cheeks twitching like crazy, palms sweaty, throat aching from all the guttural sobs.

“When did you find out about me, Tiffany?”

“Right before Mom moved into hospice care. She told me then. She said when she died she wanted me to live with you.”

“But before that. What did she tell you about your father?”

“Artificial insemination. She said she wanted a child and that’s how I was conceived. All my life that’s what I’ve thought.”

He lowers his head into his hand, rubbing his temples, and I take a quick moment to study his hair again. That soft, silky mixed-people hair. Not like my kinky hair, not even close. He looks up and his bright blue eyes stare into my dark brown ones. Uggh. We don’t look anything alike.

“We have to find a way to move on from here.” Anthony places a hand on my knee and I instinctively jerk away. He looks stunned. “Tiffany, I apologize if that made you uncomfortable.”

“I’m nervous,” I admit, feeling terribly guilty for shutting down his first attempt at affection. “I’m really sorry.”

“Would it make you feel more comfortable if Margaret were here with us? She wanted to give us privacy but I can have her come sit here while we talk.”

“No, no. I’m not scared of you or anything like that. I’m just...” Afraid you’re not my real dad. That’s how I’d like to end that sentence.

“I’m actually from Chicago, you know,” he says with a hint of embarrassment in his voice. Like being from Chicago is equivalent to being from Mordor. “Born and raised in Englewood. We moved to California when I was thirteen.”

I give him a curious look. Englewood has to be one of the worst neighborhoods in Chicago. Anthony doesn’t strike me as the Englewood type.

“Do you have any questions for me?” he asks. “Anything at all.”

Only about a thousand. I decide to start with one of the dumbest questions I can think of. “How come you’re so light-skinned? Are you mixed with something?”

“My mother is white, Irish American. Yes. And your grandfather, my father, is African American.”

“Omigosh. Are you serious?” I cover my face with my hands again, a fresh eruption of tears wetting my face. “I’m sorry I’m crying. So, so sorry.”

“Stop apologizing, Tiffany. This must be terribly confusing for you.”

He’s right. This is terribly confusing. Oh, why did I come here? Why didn’t I just take the stupid DNA test with Xavior? What am I supposed to do now? “What...do you want me to call you?”

“You can call me Anthony if that feels comfortable. I’d prefer you to call me Dad. I’d really like that.” He reaches out and touches my hair. “Are these extensions?”

I look up. My vision blurry through my tears. “Um, yes.”

“If you’re going to live here with us, Tiffany, then I will treat you like I treat my other daughters. Same rules. You understand?”

My heart nearly stops, but I nod in understanding.

“I don’t allow extensions. You’ll have to take those out. Will you be able to have that done before school on Monday?”

“But—” I got my extensions fresh back in Chicago two days before I left. They took seven hours to put in and Grams paid nearly three hundred dollars. Plus, I can’t wear my real hair. Not yet, anyway. It’s just starting to grow back. It was about two months after Mom got her diagnosis when I got my own special diagnosis.

“Alopecia,” my longtime pediatrician, Dr. Kerstein, explained to my mom with me sobbing by her side. Beanie pulled almost to my eyes to cover all the bald patches on my head. I was rocking the sideways comb-over like the middle-aged white men do when they start to go bald. But underneath the sideways swoop of hair I looked like I had donated my head to a science experiment.

“Alopecia?” my mom replied in horror. “How in the world she get something like that?”

“Stress,” Dr. Kerstein replied sympathetically. “My instinct says it’s psychosomatic. Understandable, considering.”

After that, Mom made some changes at home. She no longer talked about her condition or all the chemo she had to endure that was making her so sick. In fact, no one was even allowed to speak the word cancer. There was a designated “crying” room because tears were no longer permitted in the main areas of the apartment. No sad movies or slow music or even regular TV. Mom mostly kept the TV on Disney Junior. Grams and I watched so many episodes of Mickey Mouse Clubhouse that we started to have existential debates about Mickey and his friends. Did Mickey age? Did his mouse parents already die? Or were they all eternal?

“Tiffany?” Anthony repeated. “Do you think you can have those braids out before school on Monday? You can’t go to school like that.”

“Could you maybe make an exception for me?” I plead. “My hair—”

“Absolutely no exceptions. I’m sorry. Rules are rules.”

Thump-thump, thump-thump: But he’s not even your real dad!

Thump-thump, thump-thump: And you’re gonna look like a troll doll without braids!

“I have alopecia,” I whisper. As if whispering can somehow cover my shame. “You know what that is?”

“Tiffany, I’m a doctor.”

“I know. Right. So you understand why I can’t take them out?”

“Perhaps I’m not communicating clearly. I don’t allow extensions. You must take them out.”

“That seems unreasonable. What about the bald spots on my head? The braids are placed strategically to cover them up. It’s no one’s business that I’m sick.”

“Alopecia’s not a terminal illness, Tiffany. We’ll get you on a vitamin therapy and we can schedule an appointment with the girls’ beautician. She’ll come up with a style you’re comfortable with.”

“You mean a style you’re comfortable with? I’m already comfortable.” I stand and move toward my new dresser. Staring blankly at the collection of music “gifted” to me.

“Tiffany—”

“Look, I’ll take them out tomorrow.”

“Good. Do you have a phone?”

“It’s in the closet.” I wipe my nose again, my back still turned to Anthony. “Do you want me to get it?”

“You can give it to me tomorrow after you’ve programmed your numbers into your new phone and I’ll send the old one back to your grandma.”

I sigh. Uggh. This is getting complicated. I spin around. “I just got that phone. It was a birthday present from Grams.”

“Margaret and I got you a phone. That’s the one you’ll be using from now on. You’re on the family plan. Only texting and phone calls allowed. No internet. And you have to hand it over every night. We keep the phones in our room so we can monitor them. That means we have all passwords. And we do read texts, so keep it PG.” He rubs his forehead in that way grown-ups do when they seem stressed or overworked. “We’re Jehovah’s Witnesses. Did you know that? Did your grandmother tell you?”

“You’re what?”

“Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

I remember Jehovah’s Witnesses knocking on our door once in Chicago. They had a pamphlet and on one of the pages were cartoon images of very happy, smiling people walking away from a burning city. At the top of the page, it said, Get Ready for Armageddon. Grams was nice, but told them proselytizing wasn’t allowed in our particular apartment complex before she swiftly shut the door. When I asked her what proselytizing meant, she said it was “when people who think they know everything annoy everybody around them.”

“As you might know,” Anthony continues, “Jehovah’s Witnesses don’t celebrate birthdays or holidays.”

“Oh. So why are you having a birthday party for me?”

“It’s a family reunion. Margaret made a cake and...we want you to feel at home here. This is your home, after all, Tiffany.” He stands. “Is it just me? I feel like we may have gotten off to a bad start.”

“Yeah, me, too.” I turn back toward the dresser and pick up a copy of The Jimi Hendrix Experience. “One of my all-time favorite songs is ‘Bold as Love.’ So cool you have this. It’s got to be one of the most beautiful things ever—”

“Let’s join the others downstairs and talk more later. Okay? We don’t want to be rude and stay away from the family too long.”

I scratch at my trembling cheek. They’ve been around him their whole lives; I’ve only had five minutes, but, “Sure. Yeah.”

“You’ll want to wash your face a bit?”

“O...kay?” Rude much? I wipe at my runny nose again, self-conscious and majorly uncomfortable. “Can I ask you one more question please?”

“That’s fine.”

“Why do you think my mom wanted you and me to take a DNA test?”

“Legal reasons, I suppose. I told her there was no need for any of that, though.”

“What did she say?”

“What do you mean?” He looks more than slightly frustrated.

“I mean, when you told her there was no need for a DNA test, was she all ‘Oh, okay, great’? Or was she like...? I mean, what did she say after that?”

Anthony folds his arms across his chest. “She thanked me for trusting her.” He smiles. But it’s not a happy smile. More of an I’m-done-talking-about-this smile. “May I hug you, Tiffany?”

I nod and he steps forward to embrace me. He smells like hospital soap and laundry detergent and his arms feel strong and defined. Like, this is a doctor who hits the gym before and after he delivers babies. But more important...they feel stiff. This time I don’t jerk away like a crazy person, but the hug still feels cold. It’s about as comforting as being embraced by the principal at my old school. And I hated that guy.

“We’re so glad to have you here. It’s a blessing to have my family all together. A real blessing.”

He leaves the room and I stand for a long moment feeling as if I’ve arrived at Disneyland to find out the whole park is closed for repairs. Or worse. Like I’m a millionaire stepping out of the Dublin airport. The sky is bright blue, and it’s a hot, sunny day.

“G’day, miss,” one of the locals would say. “Dinna unnerstan this weather, aye? So lovely. Forecast says no rain in sight. Not for a long, long time.”