Читать книгу Women Strikers Occupy Chain Stores, Win Big - Dana Frank - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление

Interview with Dana Frank

Conducted by Todd Chretien December 12, 2011

Todd Chretien: I’d like to ask you about the parallels between the Occupy Wall Street protests and the great workplace occupations carried out by workers in the 1930s in their fight for union rights. So to begin with, Dana, can you speak about the precursors that led up to the occupation at Woolworth’s? How did working people respond to the Great Depression? What were the movements, the strikes, the organizations that laid the basis for this type of action?

Dana Frank: Let’s remember exactly when this strike happened: right in the middle of the Great Depression. The U.S. economy was a total disaster since 1929. At the worst point a third of the country was unemployed and another third was underemployed. But at the same time, by 1937 when the Woolworth’s strike happened, people had a huge sense of hope because of the New Deal. The government of Franklin Delano Roosevelt had created all sorts of social programs to redistribute wealth and try to address the economic crisis. But let’s be clear: the New Deal only happened because ordinary people were taking things into their own hands with huge social protests throughout the 1930s, and that’s what got us the welfare state. We tend to think that people just roll over dead when things are terrible economically, but in reality it’s just the opposite.

The most spectacular of those social movements in the thirties was the uprising of the labor movement through the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the CIO. It organized literally millions of people. That’s when we got most of the big industrial unions that we take for granted, like the auto workers, steel, tire, electrical manufacturing. All of that was happening in 1936 and 1937. The most famous moment was when the auto workers sat down and occupied a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, for almost two months. And they beat General Motors cold. There was almost no union in there before, and they won union recognition, wage increases, and then, eventually, better and better contracts at GM.

So, in that winter of December 1936 and January 1937, the General Motors strike was going on in Flint, next door to Detroit, and it was really an astonishing thing. It was all over the headlines in the United States and all over the world for that matter, because GM was the biggest corporation in the world, and the workers completely defeated it. That victory then inspired people to all kinds of labor activism. People said, “Wow, if they can beat General Motors, anything can happen!” In fact, U.S. Steel, really soon after that, gave in to the Steel Workers Organizing Committee without a strike because it was so afraid the same thing would happen to it, too.

The Woolworth struggle was at this exact moment. These women said, “Whoa!” It wasn’t just them, either. Two or three weeks after the autoworkers won, all these little strikes started breaking out in Detroit and all over the Northeast and upper Midwest, led by workers in laundries, in restaurants, in golf ball factories. They saw that the iron was hot, that there was a window of opportunity for activism. Public opinion was on the side of the General Motors strikers. Public opinion was saying, “Wait a minute, something is very wrong in this country. The wealth is completely out of kilter in this country in terms of who’s rich and who’s poor.” Remember, General Motors was a sit-down strike, so the strikers had to have the moral authority and legitimacy to occupy private property and win. You can only do these things when people in the general public are feeling like, “They have a right to do this.” That winter and spring of 1937 was an incredible, historic moment in U.S. history.

Could you say a few things about this question of seizing or occupying private property? As we know, private property is written into our constitution, it is sacrosanct, and unions have traditionally picketed outside workplaces, workers have withdrawn their labor from companies and corporations as the primary means of taking strike action. So how and why did workers decide to move their strikes inside?

It’s important to underscore that these sit-down strikers were not trying to take property away from the owners. They were using a sit-down as a tactic while they were striking. Traditional strikes set up a picket line as big as possible around the workplace and the workers use that to prevent the employers from bringing in scabs. In a sit-down strike, you are already in there so they can’t bring in scabs. Also, you have a sense of camaraderie and spirit and creativity, because what are you going to do in there all day, right? But because it’s on somebody else’s property, there are these questions of legitimacy. When people have a sense that the corporation, or whatever the target might be, is itself illegitimate, that it’s obtained its power and wealth illegitimately, then you can have public opinion on your side. But I do want to emphasize that the strikers were not saying take the store away from Woolworth’s. They were saying, “Give us just wages, shorter hours, don’t make us pay for our uniforms.” In terms of demands, they were not saying that “we should own it.” Also, they were super, super careful to never damage a thing inside the store while they were in there.

But the Woolworth’s strike was about saying, we are going to take our bodies and we are going to put them here and we are going to make some claims. That’s what the Republic Windows and Doors workers did in 2008 in Chicago when they occupied their plant and said, “Wait a minute, you can’t just shut down this factory without paying us.” They were working with the United Electrical Workers’ union, and they won, too. So, the sit-down is a tactic, it’s about people thinking creatively about what it means to occupy something. Notions of property can shift during moments of fundamental economic crisis, such as the one we’re in now. When the system isn’t working, people start rethinking it; they challenge what’s just and what’s not.

Let’s talk about these different types of occupations. In the 1930s, workers occupied their own workplaces, which gave them a certain legitimacy, camaraderie, as you said, but in the 1960s the occupations were by customers, African Americans who challenged segregation by demanding to be served at Woolworth lunch counters. They put their bodies on the line to take that space. Now, we see Occupy Wall Street and yet another type of occupation. As we speak, the West Coast ports are being blockaded, not by longshore workers alone, but by community members, youth, students, unemployed, and activists from other unions all in solidarity with rank-and-file longshore workers, and with the active support of some of those workers, but without the official recognition of the ILWU. So, what we see is a continuum of types of occupations. There’s been a lot of talk in the mainstream press about how these new occupations are not legitimate because they are not being carried out exclusively by employees from those workplaces. So, two questions. First, in the 1930s, what was the attitude of the mainstream press and employers to sit-down strikes and, second, how do the past occupations, be they in the 1930s or 1960s, relate to what is happening today?

In the 1960s, the protests were about the rights of African American people to be served at Woolworth’s lunch counters, so they were really about customers protesting racism in consumption. Whereas in 1937, it was about the exploitation of the Woolworth workers. But these issues are not separate, right? Those same people who couldn’t get served at Woolworth’s also couldn’t get hired. Woolworth’s in 1937 would only hire white workers almost entirely. And if African American people did maybe get hired—one or two men in the stockroom, or a woman cleaning up—they would be exploited even more than the white workers.

As for today, the most obvious parallel is Walmart. Walmart is one of the biggest forces in the world driving down labor costs and working conditions, not just in its stores but equally importantly in the factories that supply it, all over the world. That’s why its products are so cheap. It creates poverty all around the globe, and then turns around and sells those products to other poor people whose poverty it has helped create, and rakes in the money. I mean, here’s Walmart. It has 1.4 million workers in the United States and 2.4 million around the world—and that’s not counting the tens, perhaps hundreds of millions of workers who manufacture the products it sells. It creates enormous wealth for the Walton family and other stockholders. Listen to this statistic: in 2007, the combined wealth of the six Walmart heirs was bigger than that of the entire poorest thirty percent of the United States’ population. That is huge! These six people have more wealth than the entire bottom third of the United States! I think those types of numbers make people realize that something is fundamentally wrong. And WalMart is just the tip of a global iceberg of corporate-generated wealth; it’s just one example.

So, what are you going to do about it? What’s awesome about the Woolworth story—and you can see this in some parts of Occupy Wall Street—is that these young women were absolutely ordinary young people, they did not have a history of activism. They saw what their brothers and boyfriends and family members had done at General Motors and they said, “Hey, we can do that too!” They believed in themselves. They knew that the iron was hot, but they also had a sense of “We can do this, just by ourselves.” They did have major help with allies in the labor movement, but it was their idea. They also knew how to sustain themselves emotionally because it was scary to be occupying a chain store in the middle of the night. The police could have blasted in at any moment. It was their bravery and their sense that enough is enough and we can take on Woolworth’s and win. And that spread all over the city and country. This wasn’t just about one group of women in one store. It spread to another store in Detroit. It spread to fifteen stores in New York City and it spread to all kinds of other stores around the U.S. It was about people believing that organizing works. And, of course, the big point of the story is that, amazingly, organizing did work. It was a complete victory.

They were also very smart and creative about running it themselves inside the store, for the most part. The initiative came from below, and I think there’s a lesson there about successful organizing. There’s a major lesson at the end of the strike, too. It was initiated and led by women, but they were cut out of the negotiation process at the end by the male union officials who came in to strike the deal with the company. So, what did that mean in terms of what we would now call union democracy and the internal democratic process of the movement? One of the things that’s been beautiful about Occupy Wall Street is to watch people developing new forms of democratic decision-making. In the case of the Woolworth’s strike, we don’t know that much about what was going on inside the store. We know they developed their own committees to run things, and had an incredible culture of resistance, as historians would call it, but we also know that at the end, the big decisions about what they’d win were not, for the most part, under their control. So, we have to think about what we are modeling when we run occupations, in terms of what kind of a society, what types of relationships among ourselves we are building, and how gender and racial politics and class differences are going to play out.

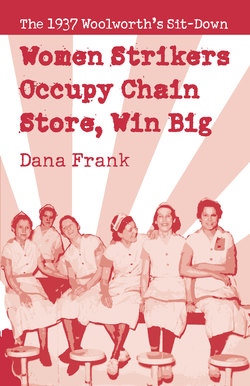

You asked about the media. Much of the mainstream media was very supportive of the Woolworth strikers—that was a big part of what made it possible for them to stay in the store, and win. The headlines I used in the text are mostly real, although I made up the original title, “Girl Strikers Occupy Chain Store, Win Big.” You would see headlines like that all the time during 1937. Today, you can see peeps here and there of sympathy—like one mainstream report on Occupy San Francisco that emphasized that the demonstrators had gone out of their way to isolate and discourage anyone who sought to damage a nearby ATM. The reporters and editors themselves are usually union members. But they’re under tremendous pressure from their own bosses. So you almost never ever see a headline that affirms that Organizing Works! Striking Gets You Health Care! Warmongers Don’t Invade Country X Because of Mass Protests!

Can you talk about this question of democracy within the occupation and the demands these young women, and we should say very young women, I think the average age was eighteen or nineteen, placed on the bosses? Within Occupy Wall Street there is a strong current of concern that raising any set of demands necessarily puts you at risk of being co-opted back into the system. So, how did Woolworth workers articulate their demands, and how, given this problem you raised about union officials taking over the negotiations, how do you see what we might call partial victories?

I have a tremendous respect for the process politics of Occupy Wall Street and the way that people have been experimenting with not moving too quickly toward saying, “Here’s our one thing we want.” They want to embrace so many issues, and that’s really important. We absolutely need to think big about connecting the dots of social injustice. I myself think, though, that you have to have some concrete demands that you can win—and then you ask for lots more! That keeps you going, while you keep driving in your point about the big changes, and groping toward the middle-level road to those changes. You do need to feel a deep sense, however small, of “Gee, we did that. Look what we got,” while simultaneously keeping clear that small steps will not solve the underlying problems. You have to have a sense as a movement that organizing worked, while being open to saying, “Wait a minute, did that lead us right back to where we were when we started?” André Gorz famously wrote in 1967 that you should ask for impossible demands that the system cannot satisfy.

In the case of the Woolworth strikers, they did win wage increases, improvements in working conditions, and union recognition, but they didn’t solve the larger structural problem of Woolworth’s as a huge capitalist firm following the logic of profit unfettered. They did put brakes on that exploitation, and they did help redistribute the wealth, if you take not just the Detroit case but all the organizing of retail clerks reaching well into the 1940s, inspired by the Woolworth’s workers. But then you have to think about whether that movement then did or didn’t contribute to a process of long-term structural change. Did it take on deep economic structures? Did it challenge capitalism, which continually regenerates wealth and inequality in its very nature?

One of the differences you raise between Woolworth’s as it existed in the 1930s and Walmart today is the fact that, if Woolworth’s began to incorporate international production into its supply chain in the 1930s, then Walmart today has taken the process to the most extreme degree possible. So, we see that most of Walmart’s consumer goods come from China, from other Asian countries, all of which has to come through the ports, making Walmart a truly international corporation. And, in terms of the workforce, if Woolworth’s refused to hire people of color in the 1930s, today Walmart employs black, white, Asian, Latino workers. They are young, middle-aged, elderly, men, women, gay, straight, and on and on. In other words, Walmart’s workforce is tremendously diverse, despite the fact that Walmart’s management retains discriminatory promotional and hiring policies. What are the specific challenges facing organizers in these circumstances?

Walmart is very specific because it is so global and so big, but the formula that it uses is the same used by Best Buy or Target or Starbucks or most any huge employer. They are looking for the cheapest labor they can get, they are driving labor costs down by making the job as simple as possible—exactly like Woolworth’s did—and they’ll take whatever cheap labor force they can find. Walmart is looking for whoever is most vulnerable and is going to have to take the job because they don’t have other opportunities, in part because of racism and sexism. Of course, we know how badly Walmart has also been discriminating at higher levels of management. It also discriminates against older people, defining positions like clerks to include stocking shelves, so older people won’t be able to do it, and the company saves on health costs. I think the sheer baldness of the way in which Walmart exploits all its workers gives people a common ground, because they know they are all getting the same bad wages, the same crummy benefits, if any. They all know they can be fired the minute their supervisor, who’s watching them on a spy camera, doesn’t like the way they just burped. It’s an opportunity for unity.

There are all kinds of historical examples of working people successfully organizing together across racial and ethnic lines. In the Lawrence, Massachusetts, textile strike of 1912, for example, workers and organizers gave their speeches in literally dozens of different immigrant languages. In packinghouse workers’ union campaigns in the 1910s, Polish, Irish, and African American workers figured out ways to strike together even though they had huge conflicts. Ethnic solidarity can aid a social movement when people draw on cultural resources in their communities to then build to broader solidarities. We know employers are always trying to drive a wedge between racial and ethnic groups. There’s a long history of that. But there’s just as long a history of people overcoming it.

One of the things that’s changing today is that poor and working people are once again starting to realize that our problems are not about people failing individually. It’s that all this company or this system has to offer me is poverty. During the Great Depression, even when everyone knew a third of the country was unemployed, a lot of people still thought at first it was their own individual failure somehow. They had to figure out it was the system that was failing them. Also, you have to believe that organizing works. Because you have to believe that if you take the risk of a sit-down strike or the risk of an occupation it’s going to pay off. And that’s where history matters. Because if you look at U.S. history, it’s full of people going out on strike, full of people occupying things, saying, “¡Basta ya!, enough already!” People are always saying, “We are in this together and the only way out is together.” But you have see that and you have to believe in that and you have to know it’s possible.

That’s why this Woolworth story is so beautiful. It’s a true story, I didn’t make it up! These were absolutely ordinary young women who had never done anything like that. Some of them were sixteen and seventeen years old. But they were also very careful about choosing the right moment because they knew that if they didn’t choose the right moment they could fry. They had the media on their side, they knew how to frame their issues, how to present themselves. You have to be very careful about those things while believing deep in yourself that we can do this together.

You don’t walk in there all by yourself and say, “Mr. Boss, would you pretty please give me a raise?” You go in there with three thousand people all at once, and you say, “This is wrong, the way you’re treating all of us, and we are not going to accept it any more, and we have lots and lots of friends out there all lined up.” You have to believe in that power and that’s what solidarity is all about. But it’s also about having a vision of a labor movement that’s not just about one group of workers. It’s about seeing the need to fight for broader social gains, including big demands on the state. Whether it’s the antiracist movement, or immigrant rights, or gay rights, it’s about seeing all of these movements as a larger fight for social justice. That’s what’s brilliant about Occupy Wall Street and the way they’ve framed this as the 1 percent against the 99 percent.

We see in the thirties that the old strategies of craft unionism and exclusion utterly fail to deal with the economic crisis and a series of new ideas and tactics replace them, like the sit-downs, occupations, and city-wide general strikes. It seems to me that today, although there are more progressive elements, labor is in a similar crisis. Less than eight percent of the working class has a union, manufacturing is globalized, millions of workers cross borders looking for work, the service sector is now huge, etc. All of this has presented the unions with a huge dilemma. It’s true that some elements in the trade union leadership have welcomed Occupy Wall Street, but others have been hostile, or remained aloof, or are worried that it is too radical or too disconnected from the Democratic Party. So there is tension over these new questions, new methods, new tactics that Occupy Wall Street is developing and the traditional labor movement’s practices. Given this, what is your opinion about the role the established trade unions can play and, perhaps, what they need to change?

There’s a long history of debate within the labor movement over whether it should be narrowly defined for just a small group of workers who get some power through their own struggles, versus seeing the labor movement as something broad that includes all working people and their concerns and their social movements to address those concerns, whether it’s immigration or gay rights or housing discrimination. The labor movement is most powerful when it understands itself as a social movement. And it’s also strongest when it understands that rank-and-file workers, their neighborhoods, and their families are the driving force of social change, not just the union officials. In the thirties, ordinary people, the rank and file, were unleashed. Better, they unleashed themselves. So that’s one big thing. The labor movement has to respect its own members and their creativity and power and their faith in themselves. This is tied in with racism and sexism at the top. We still have a problem of who top-level labor leaders are in many of our unions. People of color and women need to be in the top leadership, with power to define what the labor movement is and what its priorities are in terms of social justice on all fronts.

Historically, the labor movement has been incredibly diverse in terms of what people understand a workers’ movement to look like. In fact, what most people today understand a labor movement to be—that what a union does is have a government-sponsored election and then bargain a contract and then, if a demand is not in the contract, it doesn’t exist— that’s not what the labor movement looked like for its first hundred and fifty years. Just as important, it hasn’t always been the case that the labor movement and social movements address different forms of oppression. At its best, the labor movement has fused with and served other movements, like the women’s movement or the Black freedom movement or Chicano power.

You were trained in a school of labor history exemplified by your mentor, David Montgomery, who just recently passed away, that started from the assumption that working-class people can run the world. A lot of people will agree that we need to protest because conditions are bad and we should try to fight for some reforms but there really is no alternative to capitalism. In other words, the idea the world can be fundamentally different, as they said during the French general strike in 1968, “The boss needs you, you don’t need the boss,” is a utopia. Do you believe that labor, working-class people of all colors and nations, men and women, can run the world? Or is that simply a dream that we should put aside in the interest of more practical politics?

Of course it’s possible. You do, though, have to define working people as broadly as possible and that’s why framing this as the 99 percent is really important. I think the ordinary people who go to work every day, they don’t own big things, they don’t have a lot of power in the formal sense, but they do know how to do their job, how to run that office, or hospital or school or factory or store or port, they know how to run it as well as the boss—and usually better. Famously, secretaries are always having to teach the boss how to do their job. And we have examples today like in Argentina, where people are successfully re-opening and managing their closed factories by themselves. There’s a long history of co-ops and collectives and communes. You still have to duke it out and have a lot of arguments and a lot of meetings. Of course, you always have to have a lot of meetings! There are all sorts of other structures we know about, non-capitalist or pre-capitalist, in which societies are not based on the idea that one group of people owns things and exploits another group of people so that they can get even more money, right? Why should that be the organizing principle for how we manage our lives together? I think there is a tremendous wisdom and creativity and generosity among all people. Working people know that they could be doing it themselves, but we don’t get to practice it very often. Our systems of governing ourselves don’t have to be about these big, monolithic, global corporations paying off governments to change the rules so they have even more wealth. Then there’s the challenge of how get there from here. Of course, it’s a REALLY big challenge. How do we do it? We’re not all going to just get along and agree with each other all the time; but that doesn’t mean that we should then just agree to hand over all the wealth to the top 1 percent and say, “Thank you very much, yes, you can drive me into the ground.” People aren’t going to put up with that forever.

In the end, what the Woolworth strike shows is that regular people have this potential to change the world, and they often do. You have to believe that it’s possible and you have to have the right moment and you have to do it together. But when people do move together—and in 1937 it wasn’t just those Woolworth strikers, it was people all over Detroit, at General Motors, it was the union people, it was the money pouring in to the women from unions and individuals all over the country, it was about the people going out on strike in New York, all of it can come together. And it does come together all the time. It’s happening all over the world as we speak. We have to organize to change the world. It takes a lot of small, daily organizing as well as a lot of frustration. But when the time is right and people feel historical change they want to be part of it. Then they do change the world—and change, themselves in the process.