Читать книгу Never Suck A Dead Man's Hand: - Dana Kollmann - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

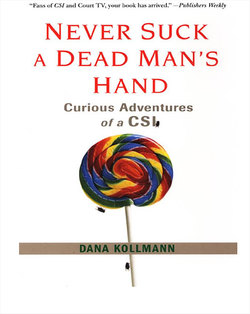

CHAPTER 2 A Sucker’s Born Every Minute…

ОглавлениеAs a real CSI, you learn a lot of things through firsthand experience that can’t be taught in a classroom, read in a book, or seen on television. In my case, I learned the most from my mistakes. It took me a few months and half a dozen bloody crime scenes before I figured out why my dogs were so eager to lick my boots when I came home from work. I wished someone had told me that I’d start a fire if I put my flashlight bulb-side down on a 1970s-era, mustard-yellow shag carpet, and I should have been warned not to place my pepper spray on a warm radiator unless I was in the mood for it to deploy on Christmas Day while the house was full of company. It only took one call before I realized that when a man and a train get into an altercation, the train always wins. I learned that wheps were welts, ramshackled was ransacked, hackers were unlicensed taxi drivers, and 40s were big strong beers. Commitment turned out to be a word reserved for Harlequin romance novels, and both men and women referred to their significant others, not as their girlfriend or boyfriend (or, God forbid, wife or husband), but as their baby’s mama or their baby’s daddy. Only once did I make the embarrassing mistake of asking a victim what he meant when he said he was out looking to “score a nickel of rock,” and within a week of working, I knew where I could pick up a do-rag and a hoodie for a big night out on the town.

One thing that I quickly learned was that dead people weren’t as pleasant as I initially thought they’d be. They certainly weren’t the friendliest bunch and many were inconsiderate and chose to break on through to the other side outdoors in the middle of a thunderstorm or on the coldest and windiest night of the year. Some made the break right at the end of my shift and caused me to work unwanted overtime and almost all of them emitted some foul odor but didn’t excuse themselves. A few didn’t even bother to put on clean socks before my visit and stunk up my van as I drove their clothing back to headquarters.

Despite my aversion to these people that I didn’t even know, my acceptance of the position in the Crime Lab confirmed my readiness and willingness to look at them, smell them, touch them, and roll them. I knew that I would have to listen to the wet sounds of happy little maggots with full tummies slithering through rotten flesh and understood that I might be occasionally asked to assist in the removal of nipple and belly button rings. Although I didn’t like the idea, I acknowledged the fact that I’d need to hold their hand as I rolled their fingerprints and shove my hand deep into their pockets as I inventoried personal effects. I agreed to make regular trips to the morgue to witness autopsies and watch as the pathologists bagged up organs and packed them inside canoed torsos kind of like how Frank Perdue hides the bag of giblets inside an Oven Stuffer Roaster. I was willing to do a lot of things that I never envisioned myself doing, but I had to draw the line somewhere. I crossed that line the day a dead man’s hand ended up in my mouth. Never suck a dead man’s hand was just one more of the many lessons that I had to learn the hard way.

My midnight shift began at 10:30 P.M. and once I left Crime Lab headquarters for my first call of the night, I didn’t return unless I had to. I handled all crime scenes that occurred in roughly a 300-square-mile area; a region that was distributed across five of the department’s nine precincts. I found it senseless to leave headquarters, drive twenty minutes to a call, then twenty minutes back to headquarters, only to get dispatched to another call in the area I had just left. I don’t know why I cared. It wasn’t my gas. One thing was certain: I never returned to the Lab between calls on the nights my supervisor worked. She was one of the nicest people I knew, but she had a lot to say at 3:30 in the morning. By that hour, I was usually struggling to stay awake and was at the height of my grumpiness. She’d chat, chat, and chat. She’d tell me about her furniture, and her car, and bingo, and her ankles, and coupons, and Salvador. I felt sad when Salvador died and wondered if she’d ever get a new parakeet.

On this bitter night, I planted my van in one of my favorite spots, which was in an empty lot adjacent to an old cemetery. I had grown to like it here because I couldn’t be seen from the road and was reasonably assured of being left alone. I had tried dozens of other hiding places, but patrol cars always seemed to find me. In my mind, if a police car was parked out in the middle of an open lot, the cop was saying, “Come talk to me!” But if the car was tucked away behind a building, the driver was saying, “Leave me the hell alone!” The problem seemed to be that I was the only person who had studied this version of Emily Post. I say that because when I was in my “leave me alone” spot, officers didn’t hesitate to pull up alongside me, roll down their window, and start to chat. They were just being friendly, nosey, or both. They usually wanted to know if I happened to have any nasty crime scene photos with me. Sometimes, they wanted to hear about the latest gross calls I handled or if I knew any details on crime scenes across town that had made the evening news. Then there were those who had friends who wanted to get into forensics and wondered if I had any advice or better yet any connections.

If I did have photos with me, I knew there would be a steady stream of invaders taking over my quiet, solitary space. It wasn’t that I minded talking; I actually liked it when the officers and I tried to top one another’s stories. But there were nights like this one when I simply hoped to be alone. The last thing I wanted to do was roll down my window and give the wind permission to bite at my face as I engaged in idle chatter. It was just that cold.

I flipped off my headlights and the interior dome light hoping I would disappear into the night. The heat was cranked and it stung my face, but my feet were still cold. The ever-present chill from the back of the van crept forward as soon as I turned the blower down. I closed my eyes as I fumbled with the heater, trying to find a happy medium. The silence of the police radio was a rare but welcome pleasure. The bad guys didn’t seem to like being wet or cold, so bad weather usually meant a slow night for Crime Lab. I prayed that I had handled my last call of the shift. The wind howled at my van and the swaying branches of the oak trees around me seemed like long fingers extending down from the night sky, reaching for the gravestones.

The sound of the wind and the sensation of the heat blowing on my face were hypnotic. Relaxing even more, I pushed my seat back but grumbled when it was abruptly stopped by the cage that separated the van’s passenger and equipment compartments. I had brought this curse on myself because I had argued for the installation of these cages to protect us from flying sledgehammers, cameras, shovels, electrostatic lifters, and print kits in the event of an accident. The ability to adjust, or more important recline, the seats was a comfort absolutely essential to a midnight shift that never seemed to be properly rested. On nights like this, I welcomed the idea of getting hit in the head with a flying sledgehammer if it meant that I could maneuver my seat into a more comfortable position.

I untied my boots, loosened the laces, and propped my feet on the dash. I didn’t like my Rocky boots even though they were supposed to be some of the better police boots out there. They dug into the tops of my feet and I untied them whenever I could. I turned up my radio’s volume, closed my eyes once again, and rested my ear on the lapel mike that dangled from my shoulder. In the years that I had spent on midnight shift, I nodded off only once, but I was paranoid it would happen again. By placing my ear over the mike and turning up the radio’s volume, I knew that if I did happen to doze, the blaring sound of someone transmitting on the radio would wake me up faster than an extra large espresso.

This is exactly what happened a few minutes later.

“Eighteen ninety-six Dispatch, can you have Crime Lab go to tac?”

I flew out of my seat and scrambled to turn down the volume. Goddamn it! I had gone from a pseudo-reclined to a fully erect position in a fraction of a second. My heart was thumping out of my chest. I rubbed my left ear and wondered if I’d ever hear again. I said every curse word I knew. Hearing the radio suddenly blare was worse than being awakened by a beeping alarm clock after a late night on the town. I was glad that I didn’t have a big cup of Dunkin Donut’s coffee sloshing around in my bladder because it would have been all over the seat.

I grabbed the microphone and without pushing the talk button pretended to berate the officer who raped me of my tranquility. What the hell’s your problem, jackass?

“Twenty-two fifteen,” dispatch was calling my number, “can you switch to tac for eighteen ninety-six?”

I wrinkled my face, rolled my eyes, and mimicked her nasally tone. 2215, can you switch to tac for 1896? I knew it wasn’t the dispatcher’s fault that it was cold, that my volume had been turned way up, that I wanted to be done for the night, that my boots hurt, that the seats didn’t recline, that my supervisor had a dead bird, or that I wanted a sledgehammer in my head—but since I couldn’t see her I could blame her. “Switchin’.” My voice came across as nasty.

The department consisted of ten precincts and each precinct had three dedicated radio channels: the main channel, a tactical (tac) channel, and a restricted channel. Calls were dispatched and received on the main channel, but if someone had something more informal to say or wanted to engage in conversation that would otherwise tie up the main channel’s air, both parties switched to tac. When the conversation was complete, both radios were switched back to the main channel and normal operation resumed. The restricted channel was the “secret” channel and Crime Lab didn’t have access to it. 1896 was a Crash Team unit and the fact that he asked me to switch to tac suggested he had a question or a favor to ask of me.

I reached down and toggled my radio to tac. “Twenty-two fifteen here.” I sounded anything but enthusiastic.

“Eighteen ninety-six, twenty-two fifteen.” I recognized the voice. It was Officer Evarts. “We need you to slide by our location to print our victim at this fatal before he goes downtown. Is that something you’ll be able to do for us?” Since Evarts was on the Crash Team, I knew his use of the word fatal referred to someone who had died in a car accident or had been hit by a car. Downtown was the jargon used to refer to the morgue.

“Uhh,” I groaned. I hated requests like these. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to help, although there was a bit of truth in that considering the weather. This situation was one of Crime Lab’s catch-22s. We couldn’t do anything to alter a body before it was autopsied unless we had the express permission of the Medical Examiner, and that included putting fingerprint ink on the victim’s hands. They rarely gave permission.

This all translated into a situation where it is the middle of the night and there is an unidentified dead person who, under ordinary circumstances, will not be autopsied until the following morning, possibly late in the morning. Only after the autopsy has been conducted can the victim be fingerprinted. Once printed, the fingerprint cards have to be relayed from the morgue to police headquarters and entered into the fingerprint database. Then investigators wait to see if the computer makes a “hit.” If there is a hit, the fingerprint examiner must confirm it by comparing the actual prints lifted from the victim with those on file. All of this has to be done before the victim’s family can be notified of the death. In the mean time, the family is probably pulling their hair out and calling the local hospitals because dad never came home from bowling last night. However, by printing the victim at the crash scene, investigators can get the identification process started immediately.

I knew Evarts wouldn’t like my answer. “I’m direct on that, but I can’t ink your victim unless the ME says it’s okay. Are they there yet?” ME is the acronym for Medical Examiner but we used it to refer to anyone from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME).

In our jurisdiction, it was unusual for the forensic pathologist (a licensed physician) to respond to a death scene. In most cases, he or she dispatched a forensic investigator. These highly trained individuals assess the scene, examine the body, and collect historical, medical, and forensic information that they call in to the on-call pathologist. Based on the information received, the pathologist determines if the body needs to come to the OCME for autopsy or if it can be released directly to a funeral home.

If it was determined that Evarts’s accident victim was going to a funeral home, then there wouldn’t be any reason that I couldn’t fingerprint him or her. But accident victims always went downtown and if the body arrived at the morgue with gobs of black ink on the hands, I’d have a lot of explaining to do. Crime scenes are the jurisdiction of the police, but dead bodies are the jurisdiction of the ME. Therefore, unless the pathologist or forensic investigator is present on the scene, the police can do nothing that will disturb a body. Among other things, they can’t move it, roll it, search it, or poke it. Every time I tell my two-year-old, “look but don’t touch” and “see with your eyes but not your hands,” I think of dead people.

When the body arrives at the morgue, the pathologist’s initial assessment consists of a review of the information collected by the forensic investigator as well as photographs of the undisturbed body at the scene. An external examination of the body and photographs of the victim and injuries are also an important, early phase of the autopsy process. Fingerprint ink applied to a victim’s hands at a crime scene might obscure small injuries, such as defensive wounds, or compromise evidence in his or her palms or beneath the fingernails. This ink would also appear in the photographs of the body taken at the time of autopsy and no one wants these photos to fall into the hands of a defense attorney, who will be prompted to ask in court, “So, Miss Crime Lab, what else did you do to the body before it went to the morgue?” The implication being that the CSI caused some of the other visible injuries to the body, planted evidence, and so on.

“Negative. The ME’s seventy-six [enroute]. We really need this guy printed.” Evarts yelled over the drone of the fire engine motors running in the background. They sounded like generators. The fire department was probably out there illuminating the accident scene with its powerful floodlights. “If we don’t print ’em now, it’s not gonna happen till later this morning. We don’t have an ID [identification]. Can you come out here and give us a hand? There’s nothin’ at all suspicious about this accident.” The bounce in his voice told me he was walking.

I looked at my watch. He was right. If I didn’t print him, Evarts wouldn’t have an ID for the victim until after lunch.

He piped in again. “I understand that you were out on a scene last week and printed a guy without using ink. Whatever you did there, we need you to do here.”

I threw my head backward onto the seat, which made the cage rattle. It was true, but how the hell did Evarts find out about it? I was learning not to do people favors anymore because somehow whatever you did for them would be translated into a new job responsibility. Recovered stolen autos, for example, presented a similar situation. The patrol officers had to fingerprint these cars themselves unless they were used in the commission of another crime. In that case, Crime Lab would take on the responsibility of vehicle processing. On a few occasions, however, we would slide by the location anyway to offer a hand, even if the car didn’t meet Crime Lab’s criteria for response. Before long, we were being requested on all recovered stolens and the same officers who we had helped a few weeks back would become irritated if we didn’t or couldn’t help them again.

I shook my head in disbelief. “Ten-four [okay], I’ll try. I’m seventy-six. Gimme about twenty [minutes].” I sounded perturbed. I toggled my radio back to the main channel before Evarts could even reply. I tied my boots and headed off.

I thought about my conversation with Evarts as I drove to the scene. It was obvious that another officer at his location told him about the John Doe I printed the preceding week. I would have been justified if I refused Evarts’s request, but on a death that was not at all suspicious, I didn’t see any harm in helping.

There are three types of fingerprints: patent, latent, and plastic. A patent fingerprint is a print that is visible to the naked eye, such as one made with blood, chocolate, grease, or fingerprint ink. The opposite of a patent print is a latent print, or a print that is invisible to the naked eye unless it is treated with chemicals, powders, or viewed under special lighting. The third type of fingerprint is a plastic print. These are three-dimensional in nature, such as prints pressed into a soft material like putty or gum.

The residues on an individual’s fingertips responsible for the deposition of latent prints primarily consist of oils and water, which are transferred from the fingertips to a surface when it is touched or handled. If there is reason to believe that a smooth and shiny surface could contain latents, the easiest method of visualizing them is to lightly dust the area with a small amount of carbon black fingerprint powder. If a print develops, it can be photographed or physically lifted from the surface. Lifting a print is simple and doesn’t involve any high-tech equipment. The sticky side of a piece of transparent tape is laid over the print and when it is peeled back, the powder sticks and the tape is then affixed to a white glossy card. This card is transported back to the Lab for subsequent examination.

When I was at the death scene the previous week and was asked to print the body, I initially refused because of the ink issue. But then it occurred to me that if I gently pressed the victim’s fingertips onto a print card, thus depositing the latent residues, and then dusted the shiny card with fingerprint powder, I might be able to get the victim’s prints. It worked!

As I approached the crash scene, I couldn’t help but notice that I wasn’t in Kansas anymore. I hadn’t passed a check-cashing booth or liquor store with bulletproof glass in the past fifteen minutes and could no longer smell fast-food grease or hear the thumping beat of the rap music blaring from the car beside me. I went from being in an ugly, urban corridor replete with corner hackers and ten-dollar hookers to a serene, rural environment marked by the occasional estate of a professional baseball or football player.

A patrol car blocked the road and the officer, who had to be freezing, detoured the few cars that approached down a side street. He had a red cone-shaped gadget screwed onto the end of his flashlight, which transformed it into a glowing traffic wand. My van was unmarked and I knew that I would be directed to follow the detour. When I didn’t turn, the officer snapped his red wand toward the side street. I just stopped in the middle of the road. I could tell he was getting mad because his strokes grew increasingly short and abrupt. A flashlight was yelling at me. When it was clear I wasn’t going to turn, the officer stomped toward my van.

I rolled down my window far enough for him to see the uniform patch on my sleeve.

“Sorry, I thought you were just another idiot driver.” He backed toward his car. “Let me back up and let you through. Be careful, it’s a solid sheet of ice down there.”

The asphalt glistened under my headlights as I drove toward the scene. I decided to park in the middle of the street to avoid the icy puddles that had accumulated along the shoulder. I sat there for a moment taking in the last bit of heat I would feel for a while. The wind tore through the open fields and rocked my van like a cradle. I slipped two pairs of glove liners over my hands and then wiggled them into a thick, fleece-lined outer pair. My cap had a wind liner that would certainly come in handy. I tugged it down as far as it would go. The wind was blowing so hard that it was difficult to open the van’s door and as soon as I got out Mother Nature slammed it closed behind me.

The loose hairs that missed getting stuffed in my cap lashed at my face like whips and it was hard to walk against the force of the wind. I thought that maybe if I had been a little slower responding, the dead guy would have blown away and Evarts would have canceled me.

I found my way through the maze of police cars and fire trucks and located Evarts, like most other officers on the scene, sitting in his warm car doing paperwork. It always looked like the police and highway workers stood around doing nothing. I didn’t know what the highway crew’s story was, but I did know that the police had to be some of the most patient people on Earth because it seemed like they were always waiting for someone. In this case, Evarts was waiting for me to print the body. Once I was through, he had to wait for the morgue transport service that would cart the dead guy away. Then he had to wait for the tow truck. The fire department couldn’t leave until the tow truck was done, and Evarts couldn’t leave until everyone else had left.

There is a protocol in place that establishes the succession of individuals to arrive at a death scene and when they are to be notified. This is done in a specific order to prevent too many people from showing up at once and rushing the work of those before them. Once an officer arrives at a scene and determines that the services of the Crime Lab are necessary, he or she puts in a request. Then the officer waits.

Although deaths are priority calls, Crime Lab’s response can be significantly delayed if we are tied up on a search warrant or another death scene. Eventually, we will get there and take pictures, make sketches, record measurements, take notes, and perform specialized processing if necessary. When Crime Lab is ready for the body to be dealt with, we call for the ME. Then we wait with the officers.

Sometime later, a forensic investigator shows up and takes photographs, conducts interviews, and examines the body. The investigator calls the details in to the forensic pathologist, who determines if an autopsy is necessary. If an autopsy is required, the OCME body transport service is requested. If no autopsy is in order, the funeral home of the family’s choice is called. Either way, we wait.

But the officers understandably get tired of all the waiting, so they frequently try to circumvent the rules, and when they do, there are problems. Oftentimes, they call for Crime Lab and the ME at the same time. They are under the false assumption that Crime Lab will get there first, do their thing, and just as they are finishing up the ME will arrive. The timing never works out. On more occasions than I could possibly count, Crime Lab arrived at a scene after the ME. When this happened, it wasn’t uncommon to find the victim pulled from his or her original location, rolled over, with his or her pockets emptied and the room turned over from searching. It wasn’t the fault of the ME, they operated under the assumption that Crime Lab had already been there. The impatient officers or their supervisors who directed them to hurry things along were the guilty ones.

I stood outside of Evarts’s car for a second, hoping he would see me. I didn’t want to have to take my hand out of my pocket to tap on his window. I had been out of my van for only a minute or so and was already shivering. I looked at the jumble of crunched car metal in the grass near Evarts’s vehicle. There was no way I could work out in that open field, in that cold, with that wind. I shuttered at the thought of taking my thick gloves off and wearing only latex to print the dead guy. Nursing school, which I absolutely despised, was looking like the good old days.

Evarts was deep in thought and I had to tap.

“Good evenin’, ma’am,” he chirped while rolling down the window. He sounded too happy for being trapped on the side of the road with a dead guy in the middle of the coldest night in history.

“Gimme hheeaatttt.” I hung through his window to snatch up some of the warmth while the wind tore at my back and made the loose fabric of my coat flap like a flag on a pole. I had handled a bunch of calls with Evarts and he regularly found me in my hiding spots. He turned the vents toward me and flipped the blower to high. The heat stung my ice-cold face, but it was a good sting, like the kind you get when you put alcohol on poison ivy.

Evarts took notice of my runny nose. My sniffs couldn’t keep up with the drips. “Don’t you dare leak on me,” he warned as he covered his papers and leaned away from my head.

“Well if your passenger’s seat wasn’t filled with all your junk, I’d get in!” I couldn’t feel my lips move when I talked. I probably looked like a ventriloquist. “You have to be nice because I’m doin’ you a favor and it won’t take much for me to reconsider!”

Evarts corrected my interpretation of the junk in the passenger’s seat. He slapped his hand loudly on the pile of papers. “This is work. Some of us in the department actually do it on occasion, ya know?” I wanted to ask if the 7-11 hot dog container poking out from the console was also work, but I was too cold to form the words.

I pressed my hands up against the vent and watched Evarts fasten the papers in his lap to a beat-up, old metal clipboard. He was always a tad bit disheveled but he was a brilliant investigator. He reminded me of Columbo.

“Not that you asked, but I’m gonna roll your guy’s fingers on print cards and then dust them. You’ll end up with ten cards, but that’s the only way I can do it.”

“I was wondering how you planned to do it.” Evarts pulled his ski gloves over his hands and readjusted his cap. “And I do appreciate the effort.”

“So, where is our little friend?” I was hoping the dead guy wasn’t still inside of the mangled car.

“He’s over there, under the sheet.” Evarts pointed in a direction opposite the car. “He was ejected.”

I saw the sheet fluttering in the field. The victim was far from the vehicle, or so it seemed to my untrained eye. I didn’t have a lot of experience interpreting accident scenes, although I found them to be one of the more interesting types of calls. If civilians were allowed on the Crash Team, I’d jump on the opportunity.

“What time did it happen?” I was bouncing on my feet as I asked the question to keep my blood moving. Evarts turned down the blower, cut off the heat, rolled up the window, and got out of the car.

“Not sure when it happened ’cuz the only witness won’t get up off the grass and talk to me.” We were in such a low-traffic area that the accident could have occurred hours ago and gone unnoticed. It looked like the guy’s car might have slipped on a patch of ice. The driver lost control, hit a tree, and then rolled a few times.

Each step toward the scene was one step farther away from the windshield created by the emergency vehicles. As we made our way into the grassy field, it was as if we had awoken the dead. Doors began to open and tired but warm officers and firefighters began to emerge into the cold, windy, floodlit night. Tears streamed out of the corners of my eyes and my lips and nose stung. I pulled my turtleneck up over my face and tugged on my wind-lined cap so there was just a small slit for me to see out of.

I was wearing so many layers that I looked like one of those kids in the toilet paper commercials who stuff their clothes with tissue for padding. I could barely bend, much less contort or twist. I was wearing silk long johns, over which were normal long johns and then my issued cargo pants. On the top, I wore a long john shirt, a turtleneck, my Kevlar vest, my uniform shirt, a uniform sweater, and my issued coat. Departmental regulations prohibited us from wearing turtlenecks, but I wore one anyway—I just made sure it was navy blue like the rest of my uniform and I rolled the neck down during roll call so my supervisor wouldn’t take notice of my dress code violation. This would give her something to add to her list of things to talk about at 3:30 in the morning. I suspected she knew, but she never mentioned it. As soon as I was alone in my van, I pulled my turtleneck up around my neck, but had to remember to roll it back down at the end of my shift. It reminded me of putting makeup on as I rode the bus to junior high school and then remembering to wipe it off on the way home so Mom wouldn’t see it.

Evarts and I scanned the ground with our flashlights. He was probably looking for evidence related to the crash and I was trying to make sure I didn’t step in something gross. As we got closer to the car, I could smell gasoline and something that reminded me of burned rubber. The vehicle itself looked like a crumpled soda can in the recycle bin. It was upside down, and it was quite evident that it had rolled because grass, mud, and branches were embedded in the roof, doors, grille, and undercarriage. The windshield was folded like an accordion and the side windows were smashed out. The front end had obviously struck a tree because there was a deep, U-shaped concavity in the grille, and twigs and bark were embedded in the crumpled metal. Glass, metal, plastic, and contents from the car’s interior were scattered along the accident path and the deep gouges in the frozen earth offered silent testimony to the force of the impact. I shined my light inside the wreckage. There was no way anyone could have survived the crash. The back of the driver’s seat was just inches from the steering wheel and the floorboard nearly touched the dash. The airbags had deployed but offered the victim little protection since his ejection indicated he probably was not restrained. The driver’s seatbelt swayed in the wind and the buckle clinked against the side of the car as if to emphasize the point. For a second, I forgot about being cold.

“Well,” I said matter of factly after taking it all in. I pointed to the Christmas tree air freshener still hanging from the twisted rearview mirror. “That could be a selling point.”

Evarts turned and motioned for me to follow him to the body. The yellow beam that emanated from his flashlight indicated that his battery was dying. He provided me with a little more history as we walked. “The car is registered to a seventy-two-year-old guy just up the road. The victim doesn’t have a wallet, but he isn’t seventy-two.”

The white sheet was conspicuous in the black, starlit field and lay close to a tree that showed recent damage. The vehicle’s hood was nearby. As we approached the body, I couldn’t help but notice the way the sheet danced eerily in the wind. It looked like the victim was trying to get up. Evarts must have noticed it too because he turned to me with a look of consternation and raised one eyebrow. I just had to ask the obvious question, “Think he’s fakin’ it?”

We stood over the body for a moment as Evarts finished briefing me. Someone had tucked the corners of the sheet under the body and secured the sides with rocks. He or she did a good job because it remained in place despite the wind. “Would you like the honors?” I didn’t have any latex gloves in my pocket, so I refused Evarts’s offer to lift the sheet. “His face didn’t hold up too good,” Evarts warned as he kicked a rock away with his foot and pulled a corner out from what I gathered was the head. Within a second, the wind took hold of the sheet and yanked it off the body. I had to duck fast to avoid getting hit in the face with the bloody fabric. I was appalled to see that Evarts hadn’t put on latex gloves and watched as he balled up the sheet wearing his ski gloves, which probably doubled as his off duty gloves. “Voila!”

The guy’s body appeared to be in pretty good shape, at least externally. His head, however, was another story. This guy was dead all right, really dead. I had a flashback to childhood cartoons. “You know, he reminds me of those Tom and Jerry episodes where they’d get flattened by the steamroller!”

Evarts didn’t miss a beat. “Yeah, but on Tom and Jerry they get back up again.”

I was shivering again and my toes stung. “Well, I’ll tell ya, if this guy gets up, I’m bailing and you’re on your own getting prints! Actually, if he gets back up maybe you can just ask him who the hell he is!” Since I didn’t have my latex gloves on, I used my boot to gently jar the victim’s arm to check for rigor mortis. His arm was still generally flaccid, but his hands were clenched in a loose fist position. They were definitely in rigor.

The postmortem interval is a term used to refer to the length of time a person has been dead. In determining the time of death, we were trained to look at the dates of newspapers stacked up on the front porch, expiration dates on the milk in the fridge, dates of messages left on the answering machine, and dates of missed appointments. We were also instructed to generally assess the degree of rigor, livor, and algor mortis development. While each of these is undoubtedly influenced by the specific conditions and circumstances of death, together, they nevertheless provide some information regarding the time of death.

Rigor mortis is Latin for the “stiffness of death” and refers to the complex metabolic cellular process that causes the muscles of the body to become rigid and inflexible in the hours following death. Rigor is first detectable in small muscle groups of the jaw, face, neck, and hands, but moves throughout the body, generally from head to toe. As a rule of thumb, rigor develops during the first twelve hours following death, stays for twelve hours, and disappears over the next twelve hours as decomposition sets in. Rigor mortis can also indicate if a body has been moved after death, as would be the case if a victim was found lying on his or her back but had his or her knees drawn up to the chest or arms in the air. Gravity would prevent someone from dying in such an unnatural position.

Livor mortis is Latin for the “blueness of death” and refers to the gravitational settling of red blood cells to vessels in the lowest areas of the body, causing a bluish-purple discoloration of the skin. Livor will occur only in vessels that can be distended by blood, so if the body is lying on a firm surface, vessels in tight contact with that surface will be compressed and devoid of discoloration. In other words, if a body is found lying on its back in an extended position, livor mortis will probably not be present on the shoulders, buttocks, or calfs since these areas are in tight contact with the ground. Like rigor mortis, livor mortis can indicate whether a body has been moved after death. If a body is found lying on its stomach, but livor is present on its back, then somebody better start asking questions.

Algor mortis is Latin for the “coolness of death” and refers to the body’s loss of heat as it approaches ambient temperature, or the temperature of the surrounding environment. Like rigor and livor mortis, the development of algor mortis is highly variable and influenced by external factors. The fact that the body temperature wasn’t even recorded by the forensic investigator in my jurisdiction spoke volumes.

I turned to Evarts, “Okay, I’ll be right back. Let me go get the tools of the trade.” There was an unwritten Crime Lab rule that you first survey a scene with only your eyes, make an initial assessment and develop a plan of action, and only then do you grab your equipment. As I walked back to my van, I heard Evarts cursing and I turned to see him flailing around with the sheet. It looked like he was trying to put it back over the body, but the sheet was flapping over his head like a sail. I thought about helping him, but only for a second.

The wind pushed at my back and sped up the pace of my walk. If I extended my arms I probably could have flown. My hands were numb, my lips were frozen, my eyes were watering, and my nose was dripping. For some unknown reason, probably force of habit, I had locked the van when I arrived at the scene and now fumbled with the keys as I desperately tried to get inside. After what seemed like an eternity, I heard the joyful sound of the lock click. I sprang inside of the van, frantically started the ignition, blasted the heat, and pressed my hands against the vents.

At first the air felt cool, really cool, but I kept my hands in place armed with the knowledge that the heat was on its way. I started to regain sensation after a few minutes and rummaged through my satchel for one of the many chemically activated hand warmers my brother bought me for Christmas. These things worked fabulously and I didn’t waste a second breaking the seal and vigorously shaking the packet so it could start to generate heat. As it warmed up, I searched behind the seats for small-or medium-sized latex gloves. I could only find extra larges. It annoyed me to no end when other investigators would use the last of something and fail to replace it. But I also had to share the blame since I hadn’t done a careful equipment and supply inspection before I took the van on the road. I grabbed a handful of extra large gloves, my hand warmer, and my print kit, enjoyed one last moment of warmth, then shut off the van and headed back into the night.

The walk back to the body was worse than I expected it to be. My brief rendezvous with the heater only teased me and made the wind scouring my face and screaming in my ears seem all that much colder. I bowed my head and stared at the ground as I walked. I was miserable. I hated my job on nights like this—but my self-pity was put in check when I thought about the family that would receive the worst imaginable news in the upcoming hours.

A small crowd of police officers and firefighters had gathered around the body. I dropped my print kit to the ground and pressed my hand warmer against my face. As I stood there, desperately trying to warm my frozen cheeks, I had to chuckle at the sight of the exposed body and the balled up sheet stashed beneath a pile of rocks. Apparently, Evarts lost his battle with the wind sail.

One of the firefighters broke the silence. “So, we hear you got some special way to get his prints.”

I was sure these guys hated running light details and would have preferred to be anywhere but here. They were doing us a huge favor by illuminating the scene and I had to be nice, even if I was cold, grumpy, and tired. “I have something that I’ll try but I don’t know if it will work or not…we shall see.” I opened my print kit and removed tape, scissors, magnetic powder, and my wand. I lined them up on the lid of my kit like surgical instruments on an operating room table.

All eyes were on me and I felt like a tiger in a circus ring expected to jump through a fiery hoop. I didn’t blame them though. After all, it wasn’t long ago that this kind of stuff used to fascinate me too—but that was before an interest turned into a job. I handed a stack of fingerprint cards to Evarts. “These are gonna blow away. Can you hold ’em and do my writing for me?”

I squatted down uncomfortably in all my layers and only after garnering the nerve did I remove my fuzzy gloves and don the thin, oversized latex pair. I realized immediately that the latex gloves were going to cause problems. Their tips extended about an inch beyond the tips of my fingers and the fit was not snug. This was going to make it hard to manipulate the victim’s rigor-laden hands. I also knew that the extra latex was going to get stuck underneath the fingerprint tape and cause the gloves to tear. Torn gloves were anything but welcome on bloody scenes.

“C’mon, tell us how you’re gonna print him with no ink,” a voice asked from behind me.

I tugged at the gloves, pulling them as far as possible over my fingers to fill the extra latex flapping at the tips. My efforts were in vain. I tucked my hands between my knees to keep them warm. I pivoted in my squat position to see who had asked the question, but the lights on the fire trucks blinded me. I turned back toward the body as I spoke. “I can’t put ink on his fingers because the ME won’t let us. Instead, I’m going to press each of his fingers onto a separate white card and then I’ll dust each one with fingerprint powder. Hopefully, the prints will come up.” I turned back toward the crowd and shielded my eyes from the lights by placing my hand over my brow. “I hope it works. This guy is pretty cold though. The guy I did the other day was fresher than this.” My choice of words elicited a few snickers and giggles. “We get the best prints from hot and sweaty hands.”

I heard someone jokingly ask if the guy I did the other day was hot and sweaty. I pretended not to hear him.

I decided to start with the dead guy’s left hand because it appeared to be less bloody. More important, if I worked on the left hand it meant my back would be to the wind. I grabbed the hand and could feel its chill through my gloves. I didn’t like dead hands because I like living hands. Hands are the first thing I look at on a living person. I really liked beat up hands that showed their owner had been out there hauling wood, mining coal, laying brick, or roping cattle. For me, looking at dead hands was akin to seeing your favorite dessert floating in the middle of a cesspool.

The color of dead people was one of the things that really took me by surprise when I first started doing this job. According to television, dead people are supposed to have blue lips and pale skin. But the only time I saw blue lips was when my brother stayed in the swimming pool for too long—and he was very much alive. The very first time I went to the morgue there was an old man lying on a gurney in the hallway. He was waiting for his turn but didn’t look like he was having a particularly good time. He just quietly lay on his back and stared at the ceiling. He must not have been a modest man because he didn’t care that he was naked and a bunch of strangers were squeezing past him to get into the autopsy room. I wondered if he ever knew that one day he’d be in this sort of predicament—that is, lying naked on a metal table in a crowded hallway. I was immediately struck by the color of the man’s skin. It was yellow and opaque and looked thick and stiff, like a callous on the heel of your foot. He reminded me of a mannequin. I could have propped him up in a department store window with the latest fall fashions on him and no one would have known the difference.

With the crowd at the accident scene anxiously watching me, I tried to extend the dead man’s fingers from their clenched position. They wouldn’t budge. I pulled and pried and tried to force his hand open, but each time I started to make progress I’d lose my grip in the supersized gloves and his hands would snap closed again, trapping mine in his. I pleaded with him to cooperate. “C’mon, help me out here.” He just laid there, ignoring me. I tried and failed again.

By now my gloves were covered in blood, which made it even more difficult to get a grip. I knew that if I could bend his fingers backward and stretch the muscle fibers, I could break the rigor for good and make his hands flaccid. Since his thumb wasn’t as difficult to get to as the other fingers, I changed my plan and managed to slip a print card beneath its pad. I pressed down only to realize that the extra latex from my glove was in the way.

My legs were falling asleep because I was squatting in all my layers. Although kneeling in the grass would have been more comfortable, along with it came the risk of putting my knee in some gross thing that broke off the dead man’s head. But there came a point when I decided that if I were to get the job done before I froze to death, I just had to go for it. I scanned the ground as best I could for anything that looked wet and pink, and once the coast was clear, I kneeled. I was back in business.

I pulled my gloves down again, got another card from Evarts, and repeated the process. I didn’t want to use too much pressure on the thumb because that would obscure the ridge detail in the fingerprint and render it useless. Once finished, I carefully lifted his thumb from the card so as not to smear the print and then let him go.

I turned to my print kit and without even thinking, grabbed my powder and contaminated the bottle with blood. It was for this very reason that I never touched anything inside my kit without wearing gloves. Based on personal experience, I thought that magnetic powder would yield better results than the standard powders that are applied with a brush. I dipped my magnetic wand into the jar and the tiny metal shavings adhered to the applicator like the puffy tentacles on the head of a dandelion. With everyone watching with anticipation, I passed the ball of powder clinging to the end of the wand over the card. A faint print emerged.

I moved the print card back and forth under the light that emanated from the fire truck. Someone behind me was nice enough to shine his flashlight over my shoulder. “Pretty good one, huh?”

The print was horrible. It was faint and there was absolutely no ridge detail whatsoever. All that developed was an outline of the thumb. My pride was bruised and my confidence disappeared. I broke the news. “It’s no good.” I was disappointed. “I’ll try another finger, but I don’t think I’m gonna have any luck. I think his hands are just too cold.”

One of the firemen couldn’t resist, “You mean he’s not hot and sweaty enough?”

I was freezing again and my hands were totally numb.

“C’mon, try again,” Evarts begged. I knew I wasn’t going to have any luck.

“I’ll try one more finger.” Evarts fumbled through the stack trying to remove a single print card with his big puffy gloves. I knelt beside the body and fumbled with the guy’s index finger. My hands barely felt like they were moving. I pulled a felt-tipped pen out of my coat pocket and used it as a lever to lift his finger. I struggled and was finally able to extend the finger just enough to slip a card underneath its pad. Prints were supposed be rolled from nail to nail, but that wasn’t going to happen. I was careful to remove the card from his hand in a way that would not smudge my work of art.

“Now for the big moment.” I turned back to my print kit.

Evarts crouched down beside me as I passed the powder over the card. Once again, the print barely took the powder and there was no ridge detail at all. I knew he was disappointed. “His hands are just too cold, that’s all it is.” I had let everyone down.

“Oh well,” he shrugged, “at least we tried. I guess we’ll name him in the morning.”

I changed out of my bloody gloves and as I started to clean up, I thought about my decision to use magnetic powder. I knew it was the right choice. Magnetic powder had several advantages over the standard variety, including the ability to develop rehumidified prints.

Rehumidify! That was the answer! I needed to huff!

“Evarts, wait a minute!” He had started back to his car. “I have an idea. The ME’s not going to be getting DNA from his fingers, right? I mean, do you see any reason why they’d want to take nail clippings or swab his hands?”

He looked puzzled. “No…why?”

“Just hold the cards for me.” I was shivering and wanted nothing more than to get away from this God awful scene, but my conscience wouldn’t let me leave without trying once more—even if that meant freezing to death. I pulled the hand warmer out of my pocket and sandwiched it between my hands while Evarts grabbed the cards. When he was ready, I tucked every last flyaway hair into my cap, put on the latex, and knelt down next to the guy like I had before, but this time I scooted as close to him as possible. “Evarts, get down here next to me and have a card ready.” I wiggled my jaw back and forth and repeatedly opened my mouth as wide as I could. Evarts just stared at me. “I’m stretching.”

I pulled my gloves down so my fingers were slid all the way up into the tips and then began my fight to extend the dead guy’s index finger. Using the pen as I had done the last time, I was finally able to pry his finger up from the palm of his hand and once I had a grip on it, I attempted to straighten it by pushing down on the knuckle. It was far from straight but I couldn’t push any harder.

I opened up as wide as I could and slowly leaned forward until the top joint of the dead guy’s finger was just inside my mouth. I prayed that he wouldn’t get the urge to touch my lips, teeth, tongue, or gums. So there I was, sitting in a field in the middle of the winter with a bunch of people that I didn’t know and a dead man’s finger in my mouth. My mother would have been proud, even if I wasn’t wearing a dress to work.

Evarts sounded like a broken record. “What the hell? What the hell? What the hell?” He just stared.

I firmly held the finger inside my mouth and prepared for the next step. I inhaled deeply and was caught off guard by the musty scent of blood and stale cigarettes on the guy’s hand. He must have been smoking right before the accident. I tried not to think about it. Then I proceeded to exhale a deep, long breath from the back of my throat, which was hot and full of humidity. After about five seconds I carefully pulled the finger out of my mouth and quickly pressed it on the card that Evarts had waiting.

Evarts just stared at me with his mouth slightly ajar and his nose wrinkled. It was the did-I-just-see-what-I-think-I-just-saw look.

I turned to my print kit and applied the magnetic powder. With only one sweep of the wand, a beautiful, perfect, dark print filled with ridge detail emerged. Evarts was elated and the firefighters clapped and hooted.

“It’s called huffing,” I said to Evarts, who was grinning from ear to ear. I covered the print with a piece of tape to prevent it from smudging and asked Evarts to write “Left Index” on the back of the card. “Sometimes prints won’t develop very nicely because the oils and moisture that were in them have evaporated. But you can put that moisture back by huffing on the print, then quickly processing it with powder.” I nodded toward the dead man. “In this case, his hands are so cold that he didn’t have enough moisture to leave a print, so I just added some to his fingertip.” You could have heard a pin drop.

Evarts made notes on the card and then proceeded to inspect the print more carefully. When he was satisfied, he circulated it among the firefighters. “And no,” he was answering a question that hadn’t been asked—at least not out loud. “I’ve never seen it done like that before either!” Evarts saw that I was in position to print the left middle finger. “Here,” he said to the firefighters as he handed them the first set of lousy prints I obtained without using the huffing method. “Compare the detail in these with the print she just got. It’s like night and day.” Evarts removed another print card from the stack and had it ready for me to grab.

I tugged the gloves down on my fingers to get rid of the extra latex at the tips and then engaged in a struggle to extend the dead guy’s middle finger while holding back the bloody thumb, index, ring, and little fingers. When I was sure I had a firm grip, I leaned forward, opened my mouth, inserted the finger, and exhaled. I was careful not to allow it to touch me as it went in and out of my mouth. Immediately, I pressed the finger on the print card that Evarts had waiting. Just like before, I dusted the card and a beautiful, dark print immediately jumped out. I covered it with tape and handed it to Evarts. “That’s the left middle.”

Despite the cold, Evarts and I got a system going and we were on a roll. Within about twenty minutes I had all but two of the fingers printed and the process had gone pretty smoothly. Since I had moved onto the right hand, my face was toward the wind and the pain was intense. However, as much as I wanted a heat break, I could see the light at the end of the tunnel and it was senseless to stop now.

As we had done with the other eight fingers, Evarts positioned himself with the card while I pried up the right ring finger and straightened it out as best as I could. I opened wide, inserted, and was in trouble before I could even begin to exhale. In a split second, I felt my numb fingers losing grip as the dead man’s hand started sliding in my bloody, oversized gloves.

In a flash, the dead man with a squashed head had freed his hand from mine and his ring finger fell to the floor of my mouth before it sprang back to its clenched position and curled over my bottom incisors, locking his bloody hand to my jaw. I could taste the cigarettes and heard Evarts shouting “Oh, God” as I pushed myself back into the grass. But he wouldn’t let go! I shook my head back and forth like a dog playing with a toy, but this was no game. I shrieked for help but my voice was muffled by the cold stranger’s hand that was pressed up against my face.

In what seemed like hours, but was probably only about three seconds, I was finally able to release his grip. I rolled around on the ground gagging, spitting, coughing, and screaming. I was appalled! I was disgusted! I was horror-struck! Suddenly, I wasn’t cold anymore. I had blood in my mouth and on my chin and one of the firemen ran to his truck and returned with the only cleaning agent he had: rubbing alcohol. I opened the bottle, filled my mouth and swished, swished, and swished. I did it again and again. I wiped my face down with the alcohol and Windex, and gargled with someone’s soda and chomped on about five sticks of gum.

Once I was cleaned up, I walked up to Evarts, who was in the crowd of firefighters probably talking about what they had just witnessed. I could tell they were trying to compose themselves as I approached. I looked at Evarts and then nodded toward the dead guy. “What the hell was he thinking?” Everyone just stared at me, not sure if I was joking. “Why do people have to act like that?” At that point everyone broke down laughing, including me. “Listen,” my eyes met those of each and every person in the group. “What happened in that field stays in that field.” But I knew better than to think they would keep this secret.

I was right. News of the incident spread like wildfire. I heard every sucking up, blood sucker, necrophilia joke in the book. Officers and other CSIs were warned not to leave me alone with a dead man because there was no telling what I might do.

Since the department considered this to be an “exposure,” the victim was tested for hepatitis and HIV and thankfully the results came back negative.

The worst part is that I never even learned the guy’s name, and he didn’t ask for my number. Some things never change and I swear, I’ll never suck on a dead man’s hand again. Been there, done that!