Читать книгу Broken - Daniel Clay - Страница 5

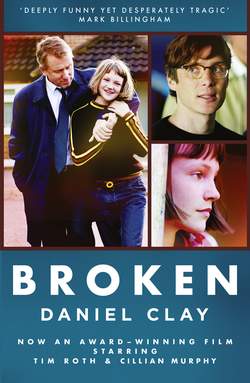

Broken

Оглавление‘Skunk, Skunk. Wake up, beautiful darling.’

Archie, my father, holds both my hands as he says this. I sense his words rather than hear them:

‘Skunk, Skunk. Wake up, beautiful darling.’

I also sense his life now.

It seeps through his palms into my palms. It deadens the blood in my veins. My heartbeat slows. I shudder. Poor old Archie. This is the way that his life is. I see it. I feel it. I know it. Tonight, from midnight through to two in the morning, he will sit all alone in the front room and watch a video of the day I was born. Almost twelve years ago now. There I am. You can see me. A wrinkled pink sack of flesh that does little but lie on its back with tubes feeding into its nostrils. Not a lot different to now then. Here I lie, on my back, with tubes feeding into my nostrils. But tonight I will be a newborn. All that hope. All that promise. Poor old Archie. He'll sit all alone and he'll watch me. He'll drink and he'll think, how did it happen? How did it end up like this? Then he'll go to the bed that he shares with Cerys and listen to her crying. He'll cry a little himself.

Finally, he will sleep and dream that the harsh ringing sound by his bedside is the Royal Hampshire County Hospital phoning to say I am dead. He will sit up, gasping, but it won't be his phone that is ringing, it will be his alarm clock, and it will be time to get up, go to work.

In work, Archie will sit at his desk and recoil every time the phone rings, then he'll rush here to see me.

‘Skunk, Skunk. Wake up, beautiful darling. Don't you leave me. Don't you dare.’

All of this will happen. I know for sure it will happen. I know everything now. Especially about Broken Buckley. Poor old Broken Buckley. Hunched over his mother's corpse. Hands pressed to his temples. How and why? Oh how and why? His story started with Saskia Oswald: Broken loved Saskia Oswald. Had. Once. Loved. Saskia. Oswald. But Saskia Oswald never loved him. She just loved his car. She said, Hey, soldier, fancy taking me for a ride? Did he? Oh, did he. Poor old Broken Buckley. He was nineteen years old and a virgin, the sort of guy who spits when he speaks, just little flecks of saliva that hang in the air and distract you from whatever he's saying. Saskia Oswald ate him for breakfast – ate him up and then spat him out. Not enough for her though. She had to tell everyone about it, and that's when it started for him.

‘Skunk, please, God, blink, just blink if you can hear me… we're here, darling. We're all here beside you.’

It didn't finish there though. It never does with the likes of the Oswalds. They're the family in one of the Housing Association properties on the opposite side of the square. Single parent. Lots of children. Music all hours of the night. Bin bags in the front garden. Portsmouth FC flags hanging from the windows. Maori-style tattoos on overdeveloped biceps. This is Bob Oswald. The father.

Bob Oswald. The father.

The first time I saw him hitting someone, I was coming up ten years old.

It was summer, hot, and Rick Buckley was washing the car his father had bought him as a present for passing his driving test. Skunk Cunningham was skipping on the tarmac drive that had once been their front garden. Other than Skunk and Rick, Drummond Square was empty.

The attack happened out of nowhere. Skunk didn't hear anyone speaking. She didn't hear anyone shouting. The first thing she heard was the scream: it was high-pitched, like a horse, and before she knew what was happening, Bob Oswald had Rick Buckley in a headlock and was twisting him sideways, like wrestling a bull. The two of them staggered out of the Buckleys' front garden and into the otherwise empty square. Rick Buckley shouted, Stop it, I haven't done anything wrong.

Bob Oswald hit him. Not a punch, but a blow with the point of his elbow. It landed in the small of Rick's back. Rick collapsed to his knees.

Skunk stood frozen, hot in the sun, her small hands held up to her mouth. Bob Oswald hit Rick again, and Rick fell flat on his face. Bob Oswald kicked him in the gut then the side of the head. Skunk recoiled at the sound of the thud. Then Bob Oswald took hold of Rick's hair and lifted his head up. He made a lot of noise dredging his throat clean, then spat into Rick's face. After that, he studied Rick closely for a moment, then pushed him back down to the ground. Rick lay very still. He was silent. Bob Oswald stepped over him and made his way back into his house. Once inside, the throb of music that had played like a soundtrack in the background rose to a deafening thud.

As far as I can remember, after Bob Oswald left him, Rick stayed on his face in the road. He was sobbing. I wanted to go and get someone to help him, but I was too frightened to move. I stood with my hands raised to my mouth and my heart beating fast in my chest. Maybe as much as half an hour later, Mr Buckley returned from the funeral parlour he managed and helped his son into their house. I sat down on the kerbside and stared at the blood on the tarmac. I don't remember if I cried. I don't remember if I was sick. If I ever asked Jed or Archie about it, I don't remember what they said. In fact, before I fell into this coma, the only thing I really remember about seeing what Bob Oswald did to Rick Buckley was trying to forget it had happened. Even though this is how it all started, I pushed the whole thing from my mind.

The police turned up three days later. The squad car stood out like a beacon as it sat on the Buckleys' front drive. Bob Oswald saw it through his kitchen window and thought about what he should do. Finally, he stepped out of his house and leaned against his jeep. From here, he watched the Buckley house until the policemen let themselves out. Then he marched over towards them.

‘You,’ he shouted. ‘I want words with you.’

The two policemen looked at each other and sighed. The Buckleys had just told them how Bob Oswald had beaten their son up for no apparent reason, but with no known witnesses and no permanent damage done, the officers had convinced Mr and Mrs Buckley to let the matter drop: if what they'd heard about Bob Oswald was true, he was only going to deny attacking their son, and did the Buckleys really want to be involved in a drawn-out court case with someone who lived so close to them? Now Bob Oswald continued towards the two policemen. A huge man, shaven-headed, he yelled, ‘I want to report a rape.’

It was his third eldest daughter who had been raped.

She was a skinny slip of a girl with lank blonde hair and an underfed gymnast's body. She never wore many clothes - hot pants, bra tops, stilettos. Her favourite expression was fucker, as in, that fucker over there's giving me the evils, or, that fucker down the road wants to watch herself or I'll do her.

Now that fucker Rick Buckley had raped her.

She told her father this just a few minutes before the fight in the square, though she never said it was rape, she only said it was sex, and she only said it was sex because he refused to believe the real reason she had contraceptives under her bed.

He said, Susan, you're thirteen years old, what the fuck do you want the pill for?

She said, I dunno.

He said, Yes, you do, you want them for having sex.

And then he got very angry.

Which made Susan very scared.

So she said that she'd nicked them.

For once, she was telling the truth. She'd nicked them off Mrs McCluskey, who'd made the fatal mistake of leaving an open handbag within reaching range of an Oswald. Mrs McCluskey never did realise they'd been stolen. She just assumed she'd lost them and got another prescription. As teachers go, she was sensible like that. As for Susan Oswald, once she'd nicked them, she didn't know what to do with them. They tasted of nothing and didn't get her going the way her old man's vodka did. What good were contraceptives? She chucked them under her bed and forgot they even existed. Bob Oswald found them six months later when he was looking for a new place to hide his drugs. He yelled, ‘Susan. Get up here.’

Susan Oswald sighed. Her old man. He could be a right fucker.

‘What?’

‘Get your arse up here,’ Bob yelled. ‘Now.’

Susan climbed the stairs. ‘What?’

Bob Oswald threw the contraceptives at her. ‘What are these?’

‘I dunno.’

‘Yes, you do. They're contraceptives.’

A pregnant pause.

‘Your contraceptives. I found them under your bed. Susan. You're thirteen years old. What the fuck do you want the pill for?’

‘I dunno.’

‘Yes, you do. You want them for having sex. Who the fuck are you having sex with?’

Susan Oswald didn't answer. She couldn't. She hadn't been having sex with anyone. Bob Oswald leaned into her face.

‘Susan. Tell me. And don't try to give me no bullshit. I know you've been at it with someone. It's written all over your face.’

‘Dad, it isn't, I haven't.’

‘Then what are you on the pill for?’

‘I'm not. Those tablets ain't mine.’

‘Yeah. Right. Whose are they? Saskia's? Saraya's?’

‘Nobody's.’

‘Nobody's?’

‘Nobody's. I nicked them. I swear.’

Bob Oswald drew a fist back. ‘Nobody nicks the pill, Susan. You get it for free off the state.’

Susan stared open-mouthed at her father's fist.

‘Tell me,’ he told her. ‘Who are you having sex with?’

‘Dad –’

‘Don't “Dad” me, Susan. Give me a name.’

‘But, Dad –’

Bob Oswald punched the wall beside Susan's head. She screamed and fell down on the floor. Bob leaned down above her and pressed his bleeding fist into her face.

‘I want a name, Susan. You're gonna give me a name. If you don't give me a name, I'm gonna count to ten, and if I've not got a name by the time I've counted to ten, I'll be punching you, not the fucking wall. You get me? I don't want to. You're my daughter. I love you. I'm out to protect you. But if you don't help me protect you, I'll break every bone in your body. Now give me the dumb fucker's name.’

Susan Oswald had never been punched by her father before. Staring into his knuckles, she didn't want to be either. They were huge. His onyx rings would slice through her flesh. She sobbed and screamed that the tablets weren't hers, but Bob drew his fist back and started to count. One, he said, two, he said, three. Susan screamed for someone to help her, but her sisters were cowering on the stairs and there was nobody else who could hear. Bob's voice rose with each number, so it was four, tell me, five, tell me, six, you'd better fucking tell me, SEVEN, right into her face. Then he screamed EIGHT, I'm gonna kill you, I'll break every bone in your body. Give me the dumb fucker's name. NINE. He tensed his fist even tighter. The knuckles were dripping with blood. Seeing it before her, Susan gave up trying to reason. She had to come up with a name. But there was no name she could think of, because there was no one she had shagged. She did know, however, that Saskia, her second eldest sister, had recently shagged Rick Buckley, the weird kid from the other side of the square. Susan knew this because she'd heard Saskia talking about the size of Rick's penis. Saraya, the eldest, had yelled, ‘How small? You're like totally kidding me,’ then the two sisters had laughed hysterically. Now, just before Bob could scream TEN and start punching, Susan shouted up into his face:

‘Rick Buckley.’

‘Rick Buckley?’ Bob Oswald stared, wide-eyed. ‘He's – what ȓ seven years older than you are?’

Rick was six years older. Bob didn't care much for maths.

Susan tried to make the lie convincing: ‘We've been doing it in his car.’

‘Fucking hell.’

Fucking hell, the two policemen thought. Rape?

They looked back at the house they'd just come from. The Buckleys seemed a nice enough family. The old man was a bit wet and the mum was a bit dull. In keeping with the parents, the boy had seemed a little bit flaky when Mrs Buckley had finally got him to come out of his bedroom and tell them who'd beaten him up for no apparent reason. But rape? He didn't look capable of sex, let alone rape.

Still. An allegation was an allegation.

They radioed it through to the Child Protection Unit, then went for a chat with Bob Oswald. As he filled them in on the details, they looked through the grimy kitchen window at a beaming Susan Oswald. She was doing dance steps with her two younger sisters in a scruffy wasteland of a garden full of swings and beaten-up toys. When one of her younger sisters got her steps wrong, Susan's beam was shattered. You stupid fucking bitch, Sunrise. You do it like this, not that. Sunset, the youngest of Bob's daughters at two years old, looked from one sister to the other, then threw her arms around both. The policemen turned away. Bob Oswald told them Susan's version of how it had happened: Rick Buckley – always a bit of a weirdo, very quiet, very, very creepy – had offered to take her for a drive in the brand-new car his old man had just bought him as a present for passing his test. He had driven her onto the nearby Oak Tree Place development that was currently just a wasteland of unfinished houses and mudflats, held her down, and raped her.

Both of the policemen took notes.

Just over eleven miles away, in Winchester, seven officers of various rank climbed into an assortment of cars and made their way out to Hedge End. Within fifty-six minutes of the allegation being made Rick Buckley was arrested under suspicion of raping Susan Oswald. In the back of a squad car that smelled of burgers and cigarettes, a constable twice Rick's age leaned in close against him and whispered, very thickly, I hope for your sake you didn't do it. Otherwise, you're dead.

The officer on the other side of him said, She's thirteen years old, you wanker.

Back at the Oswalds' place, Susan Oswald was observed as she played with her younger sisters by two highly trained social workers and the Woman Police Constable who would be her chaperone throughout the investigation. All three women noticed the child swung from agitated to content to agitated again. The social workers took notes. The WPC asked some loaded questions. She got some loaded answers. At just after seven thirty, Susan, Bob, the social workers and the police all made their way from Hedge End to the rape suite in Winchester.

In the Buckley home, Mr and Mrs Buckley sat at their kitchen table and watched as officers carried items of Rick's clothing from the house. Mr Buckley put his head in his hands. Mrs Buckley didn't hide her tears. They ran freely down her face and fell to the table from her chin. Upstairs, the discovery of a small collection of porn was greeted with satisfaction.

In the rape suite, Susan was put in a room with a PlayStation and some dolls and pens and paper and jigsaws and brightly coloured walls. The WPC who would be her chaperone sat with her to make sure she was OK. It was at this stage that Susan began to suspect she had done something wrong: people were never this nice to her, and no one ever let her use their stuff for nothing. She said, What's all this about?

The WPC said, Nothing.

Susan was not fooled.

‘Is it about what I told my old man about Rick Buckley?’

The WPC said, There's no need to look frightened, honey. You haven't done anything wrong.

Susan Oswald thought, Shit.

It was then that the police doctor came in. She was a very tall, very thin woman who tried her best to disguise the fact she hated children.

‘Hello, Susan. How are you?’

Susan said, ‘What's it gotta do with you?’ She looked from the WPC to the doctor then down at the PlayStation control in her hands. She thought, Shit, shit, shit, shit, shit.

The WPC said, ‘This is Dr Mortimer, Susan. Her first name's Susan too.’

‘Big fucking deal.’

The WPC smiled. ‘She just needs to look at you a moment. Examine you. Make sure you're OK. There's nothing for you to be afraid of. I can stay with you, if you like.’

‘Whatever.’ Susan stared at the doctor. The doctor stared at Susan. Then she took a step forward. With the curtains drawn and the door shut, it took a matter of minutes to determine Susan Oswald was a virgin. The doctor stood back and took her gloves off.

She said, ‘I'd best go and speak to DS Westbury.’

The police questioned Dr Mortimer for a further half an hour. They said, Even if Susan Oswald is a virgin, couldn't she have been interfered with? Couldn't the act of sexual intercourse have been simulated? Shouldn't we ask her to describe Rick Buckley's penis? The doctor said, For Christ's sake, the child's lying. It's written all over her face.

Bob Oswald had to be restrained when this was put to him. My Susan's many things, but she ain't no fucking liar. Bob Oswald was many things, and he was a fucking liar. Susan lied to him all the time. She got it from her father. He folded his arms and said, That man's been at my daughter. My little baby girl. She's only thirteen years old. How the hell do I get her through this? He took a deep breath. There were tears in his eyes. I want him charged. I want him strung up by his bollocks. Pervert. Fucking creep. If you don't kill him, I will. He's ruined my poor baby's life.

Detective Sergeant Westbury ran his hands through his thick brown hair.

‘Look, Mr Oswald. If Rick Buckley has been sniffing around your little girl, I want him off the streets as much as you do. But try to see this from my point of view. I've got your daughter saying she's been raped, and I've got a doctor saying she's a virgin.’

‘Then get a second opinion.’

‘Well. I'm not so keen to put your daughter through another internal examination. How about we bring her in here and have a little chat with her? Just see if we can clarify things a little?’

Bob Oswald raised his eyes up towards the ceiling.

Fifteen minutes later Susan turned on him and yelled, ‘I never said he raped me. I said we had sex. And I only said we had sex cos you made me, cos you wouldn't bloody believe me. I don't even know Rick bloody Buckley. I told you those tablets weren't mine.’

She put her head in her hands and because she knew she was really in trouble this time, Susan Oswald wept.

The adults in the room were silent. Then DS Westbury leaned forward.

‘Susan. I want you to listen to me. I want you to listen very carefully. I don't want you to be scared. I don't want you to be frightened. If Rick Buckley's done something, said something, been anywhere near you or exposed himself to you in any sort of way – or even if he hasn't, even if he's just done something to make you feel vulnerable, or threatened, or maybe just suspicious even – I want you to know you can tell us, and whatever Rick Buckley has said to you, or whatever he might have threatened you with, or whatever he might have done to you in the past… well, we won't let it happen again. We're all on your side here, Susan. All of us. So feel free to tell us what happened.’

‘Nothing, you silly fucker. Nothing bloody happened. Jesus. Jesus Christ.’

Bob Oswald shook his head. He cleared his throat. ‘Something must have happened,’ he yelled at everyone who was staring at him. ‘Look at her. She's terrified. He must have threatened her somehow. She's lying to cover his back.’

The WPC cuddled Susan. She whispered, It's OK, sweetie. You don't have to cry. Susan Oswald cried harder. DS Westbury stood up.

‘OK,’ he said. ‘I suggest a comfort break. Susan. Would you like a game of Sonic the Hedgehog? WPC Davies can get up to level eight.’

Susan was led away. She was given a cup of hot chocolate. She was allowed to play Sonic the Hedgehog. Her tears dried. Her mood brightened. She had learned a valuable lesson: sex was good. It got you attention. It got you affection. It was a good way to get on in life.

And if these things came from just saying she'd done it, she couldn't wait to start doing it for real.

The two Oswalds were dropped off by a squad car at three o'clock the next morning. Caught between charging them with wasting police time and Bob's blind insistence that something had gone on between Rick Buckley and his daughter, the police decided to do nothing. No caution. No slap on the wrist. Free to go.

The same was now true of Rick Buckley. The charges against him were dropped and, as they hadn't been sent to the lab yet, the clothes he had been wearing when he'd been arrested were handed back in a clear plastic bag. In a cold room with bright white lighting, Rick hurriedly dressed in front of two male constables and a female nurse who watched his shrivelled penis bob as he stepped into light blue Y-fronts and then pulled up his trousers. Despite his total humiliation, Rick Buckley did not cry: he finished getting dressed, he put his watch on, he signed for the loose change that had been in his pockets. One of the officers marched him down a darkly lit corridor and out into early morning. It was just after 7 a.m.

No one had told Mr and Mrs Buckley their son was being released without charge. Rick stood in a dreary drizzle and, as he had hardly any money and hadn't had his mobile phone on him when he'd been arrested, started the eleven-mile walk to Hedge End. Rain saturated his wavy hair and thin summer cotton T-shirt. He walked with his arms wrapped around himself. He walked with his head down. He talked as he walked.

On each first step he said, I.

On each second step he said, feel.

On each third step he said, dirty.

He said these words over and over.

I feel dirty. I feel dirty. I feel dirty.

He said them all the way home.

It was 11 a.m. by the time he got back to Drummond Square. I don't remember seeing him hurry round the corner and disappear down the Buckleys' side alley, but I do remember Mr Buckley coming over to our house later that evening. I was pretending to be asleep in Archie's lap. He had his hands in my hair. I could hear the depth of his voice through the itch of his polyester shirt. Mr Buckley's voice was distant in contrast.

‘The police were utterly useless. They ignored what we said about Bob Oswald, then took every word he said on oath. You know, after they dragged my son down the station, they stripped him naked and took loads of swabs.’

‘They couldn't have done that without his permission.’

‘He didn't know what he was agreeing to. Since he took that beating, he doesn't seem to know if he's coming or going.’

‘You should have phoned me,’ Archie said. ‘I really wish you'd phoned me.’

‘It all happened so quickly. We didn't know what we should do.’

I looked over at Mr Buckley. I didn't really know him, but I couldn't imagine Mrs Buckley not knowing what she should do. After my father, she was the cleverest person in the square. Sometimes, when she was out in her front garden, I'd go over and ask her about multiplication or spelling and she always knew the right answers. How could she not have known to call my father? She must have known he was a solicitor. I'd told her about loads of his trials.

‘That bloody Bob Oswald,’ Mr Buckley continued. ‘He's reduced my son to a nervous wreck and got away without even a caution.’

‘You need to go back to the police, Dave.’ Archie's voice rumbled from deep inside his stomach. ‘A vicious attack on a nineteen-year-old boy…no matter what Bob Oswald thought he'd been up to … they have to do something about that.’

Mr Buckley laughed in a way I found scary. ‘What like? An ASBO? A caution?’

‘It's GBH at least,’ Archie said after a moment. ‘Bob should be facing prison.’

Mr Buckley's voice was high and shaky where my father's was soft and deep. ‘You know better than I do he'll be facing no more than community service. What'll probably happen is the police'll decide to charge me with wasting their time. It's been an eye-opener, this has. A real bloody shock.’

A long silence followed. Finally, Archie broke it.

‘How's the boy, anyway?’

Mr Buckley's voice went from shaky to jumpy. ‘Broken,’ he said. ‘Utterly broken. He reckons he's never leaving the house again.’

Another silence followed. I was very nearly asleep. It was way, way past my bedtime. Only Archie's voice kept me awake.

‘He just needs time,’ he said to Mr Buckley. ‘Don't worry. He'll be OK.’

But Archie was wrong. Mr Buckley's son was not OK. Just as he'd said to his father, he stayed inside the house. The car he had been cleaning the day Bob Oswald attacked him stood unused on the drive. The curtains to his room stayed shut.

For a time, he was a topic of fascination to me: Has he come out yet, Daddy? Never you mind. What's he doing in there, Daddy? Never you mind. Do you think we should go round and see him? Keep your bloody nose out of other people's business, for Christ's sake, I won't tell you again. Leave the poor Buckleys alone.

Jed was fascinated as well. Why would anyone want to stay in their bedroom when there were so many things to be done? He, being older, got a little more sense out of our father, who told him Mr Buckley's son had suffered a breakdown, and people who suffered breakdowns did things differently to everyone else. Jed still didn't understand though. Why had he suffered a breakdown? Archie shrugged. Some people just do.

This fuelled our fascination. A breakdown? What, like a car? Would a man from the AA come round and jump-start Mr Buckley's son, or tow him away in a tow truck? Eager to see how it ended, we sat on the kerb outside our house. Here, we watched the Buckley place for further developments. As we didn't know Mr Buckley's son's name, we started calling him Broken, as in, any sign of Broken Buckley yet? Nope. Oh. OK. After about an hour of watching, we got bored of just sitting, so we played football while we watched, then rode our scooters up and down the pavement, honking our horns at each other.

‘You kids shut that row up,’ Bob Oswald yelled as he stepped out into the sunshine. And then, seeing Mr Buckley on his knees in his garden, ‘Hey, fuckwit, how's your rapist son healing up?’ When he didn't get an answer, he spat in Mr Buckley's direction, then got in his jeep and sped off. The deep thud of bass music echoed in his wake.

Mr Buckley stood with a small trowel in his hand and stared off into the distance. He stood there for a long time, then dropped the trowel and went inside. The slam of the door seemed final, but ten or so minutes later Mrs Buckley came out and picked the trowel up. The Buckleys were tidy like that.

Later, when Bob Oswald pulled up in his jeep, Mr Buckley came out of his house as if he'd been waiting. ‘You,’ he shouted. ‘Yes. You.’ Bob Oswald got out of his jeep and turned towards Mr Buckley ‘Yes, you,’ Mr Buckley repeated. ‘I want words with you.’ Bob Oswald raised his eyebrows. He put on a voice that wasn't his own. ‘You talkin' to me?’ He was smiling, but he didn't look happy.

Mr Buckley kept right on towards him. ‘I don't know how you can live with yourself. My son. He hasn't done anything to you or your family. Now look at him. Your big mouth and your lying bitch of a daughter. You've made him a nervous wreck. You're a wanker. You're complete fucking scum.’

Beside me, Jed sucked his breath in. Even Bob Oswald straightened a little.

‘You want to come over here and say that? Or do you want to call the police like last time?’

Mr Buckley kept walking towards him. ‘It wasn't my son who shouted rape, was it? Why did you have to go picking on him? Why does it always have to be violence with you? If you had your suspicions, why didn't you just call the police like a civilised human being?’ Mr Buckley was in front of Bob Oswald now. Bob Oswald was looking down on him. He had his hands on his hips. His thick black Maori-style tattoos stood out on his arms and his shoulders. Mr Buckley continued. ‘My son was just minding his own business. Now he won't even leave his bedroom. All because of your fists and your bitch of a daughter's lies. I don't know –'

Mr Buckley stopped talking when Bob Oswald kneed him between the legs. Mr Buckley cried out and fell down in a heap. Bob Oswald bent low and patted Mr Buckley on the shoulder. Then he made his way back into his house. Drawn out by the sound of raised voices, all five of his daughters were lined up on the front doorstep. They greeted Bob Oswald like he had just done something clever:

Good one, Dad.

That showed him.

The fucker.

Bob Oswald ushered them all inside. As Susan Oswald turned away, she looked over at Jed and smiled. Jed looked down at the ground. I looked at Mr Buckley. He was dragging himself away from the Oswald house, half standing, half on his knees. I felt sorry for him. He looked silly. He looked sad. I shouted, Hello, Mr Buckley, hot today, isn't it? But he ignored me. He went inside.

If Mr Buckley ever tried to have a punch-up with Bob Oswald again, I wasn't there to see it. Come to think of it, the only time I really saw Mr Buckley for a long time after that was whenever he came round to see Archie. I don't think he and my father were friends, exactly, but they were the same age and both supported Southampton, so at least they had that in common. Three or four times a year Mr Buckley would come over with a four-pack of Carlsberg and the two men would swear at the widescreen. Jed would watch as well, so even though I hated football I'd often drift in to join them. As an aside, once Southampton had been beaten, Archie would ask after Mr Buckley's son, who he never referred to by name. How's the boy? Or, how's he doing? Or, any news? But, finally, Archie stopped asking, and I can't really blame him. It's not like he ever got a straight answer. Mr Buckley would shrug and say something like, oh, you know, or, no change, or, same as ever, really The last time I ever heard Archie ask him, Mr Buckley said nothing. He put his hands over his face and shook his head. When Mr Buckley's shoulders started to shake, Archie gave me and Jed a tenner to go and buy chips for our tea. As far as I can tell, neither of them mentioned Mr Buckley's son after that. It was as if he no longer existed. He did though, in his bedroom, and one day he would come out.

It wouldn't be for more than a year, though.

This year was long and hard for the Buckleys. Although all charges had been dropped, and although everyone outside of the Oswalds’ accepted Susan had been lying, her accusations somehow stuck. This was mostly due to the other Oswald girls, who would scream rapist across the street every time they saw a Buckley moving about in broad daylight. Once in a while, minor acts of vandalism occurred – Broken's car had its tyres slashed, and some eggs were thrown at the house that Halloween. Rubbish was tossed into their garden, and cigarettes were stubbed out on their UPVC window frames. Nothing to call the police for. Just enough to make life unpleasant.

If Bob Oswald ever saw Mr Buckley in the street, he would always shout something, but Mr Buckley would never respond. One time, Archie Cunningham intervened on Mr Buckley's behalf. He had just taken Jed and Skunk to see Revenge of the Sith at the Odeon in Port Solent, and Mr Buckley was carrying some shopping into his house. Bob Oswald was standing on his doorstep with his huge hands cupped around his huge mouth. ‘How's your prick of a son doing, Buckley? Still touching up the kiddies?’ Mr Buckley hurried into his house and slammed the door behind him.

Archie said, ‘Stay in the car,’ then got out and walked to the edge of the drive. Jed and Skunk wound down the windows so they could hear what the adults were saying.

‘Hey, Bob,’ Archie shouted. ‘You up to speed on your libel laws?’

Bob Oswald turned his gaze from the Buckley house to Archie Cunningham.

‘What the fuck's it gotta do with you?’

‘Well, if Dave or his son wanted me to represent them, I'd be happy to do it for free. Open-and-shut case, considering the police dropped all charges. Like taking candy off a kid, taking money off you.’

Bob Oswald stared at Archie Cunningham. ‘Answer me one question, Cunningham. You let your kids go over the Buckleys'?’

‘More often than I let them go over yours.’

Bob Oswald said nothing.

Archie took a steady step forward. ‘You watch your big mouth in future. And if you ever want legal aid again don't come running to my firm. Get me?’ He stared at Bob Oswald, then turned and ordered Skunk and Jed inside. ‘I don't want you playing with the Oswalds any more,’ he said as they took their coats off. Skunk and Jed raised their eyebrows: like they ever played with the Oswalds. All of the Oswalds were mental. But so, too, was Broken Buckley: he crouched down by his bedroom window and watched his father scurry away from Bob Oswald, then watched Archie Cunningham shout Bob Oswald down in the street. Fearing Bob Oswald might look up and see him, Broken moved away from the curtains and sat down on the edge of his bed. Hunching his shoulders forwards, he tormented himself with memories of the day Bob Oswald attacked him. Then he remembered the policemen coming to get him after Susan Oswald accused him of rape. These memories were nothing compared to the day Saskia Oswald came on to him and then laughed at the size of his penis. Why did she have to go and do that? Why did she do that to him? Broken didn't know. He couldn't understand. Still, though, he went through it over and over, hidden away in his box room, curled on his side on his bed. Sometimes, he stared through a gap in the curtains. If he ever saw Bob Oswald, he relived the day of his beating. If he ever saw Saskia Oswald, he stepped quickly away from the window and paced up and down his small room. Outside of his bedroom, the world continued without him. Time passed without him emerging: days and weeks and months. He didn't just refuse to come out – he refused to open the windows or the curtains or even the bedroom door. He went to the toilet in a bucket and brought it out when Mr Buckley was at work and Mrs Buckley was out shopping. For the rest of the time he lived in a strange world of curtains, shadows and dread. His parents were despairing. Mrs Buckley, on the landing:

‘Rick. Rick. Are you in there, Rick? Can you hear me? Can I come in? Love? Please? Love? Please?’

Silence. A chair wedged under the handle. If Mrs Buckley listened, she could hear him, breathing. If she came home unexpectedly, she could hear his footsteps, scurrying, up the stairs. Late at night or in the small hours of the morning, she could hear him moving about in the kitchen, making himself something to eat. She would nudge Mr Buckley awake.

‘David,’ she'd say. ‘David. Wake up. Quickly. He's down there. Listen. He's downstairs. He's moving about.’

Mr Buckley wouldn't answer, though he hadn't been asleep. He had been listening too. And thinking. And trying not to cry. In the daytime, he tended dead bodies at the funeral parlour he managed. He sat and watched the bereaved deal with death. He held out tissues. He powdered dry cheeks. He lifted the limbs of virgins and put the corpses of babies in boxes. He applied make-up where coroners cut. And at nighttime, in the dark times, he lay on his back and he listened to the ghost of his son scrape around in the kitchen.

His wife said, ‘We have to do something.’

‘I know. But what can we do?’

‘I don't know. But we have to do something.’

‘I know. But what can we do?’

Mr Buckley knew what he had to do. He just didn't want to do it. He didn't want to go to the doctor. He didn't want to sit down before a man who was two years younger than he was, a man he remembered from school as a corn-sheaf of a child who would sit at the back of the assembly with a stupid blank expression all over his dim empty face. He didn't want to say, my one son is mad.

My one son is mad.

He never actually said this.

What he said was:

‘It's Rick. He's having some problems.’

Dr Carter sat back in his chair and looked at the undertaker with dry biscuit eyes through lashes of dust. He thought about his golf swing.

‘Uh-huh.’

Mr Buckley nodded. ‘He's not acting himself.’

‘Uh-huh.’

Mr Buckley did not say any more.

Dr Carter stared at him. Finally, he relented. ‘In what way has he not been acting himself?’

Mr Buckley cleared his throat. Then he shut his eyes. As he talked, he thought of Rick sitting on a swing on an autumn day that had never existed. On this autumn day that had never existed, Mr Buckley was pushing Rick – who was five – higher and higher and higher. Rick was clinging to the thin grey metal chains that held the swing to its rusty old frame. A sharp, dry breeze was blowing leaves into a sandpit and the rest of the playground was empty. Faster, Daddy, faster. The sound of laughter. The scrape of leaves. The glint of sunshine through a darkness that hadn't quite fallen. Mr Buckley said, ‘He won't leave his room. He won't eat any food that we cook him. He compulsively washes his body. He isn't acting himself’.

Dr Carter shrugged. ‘Why don't you tell him to pop down? I'll have a chat.’

‘He won't leave his room, let alone the house.’

‘Is he being aggressive towards you?’

‘No.’

‘Then tell him to pop down. I'll have a chat.’

‘Doctor. He won't leave his room. Let alone the house.’

Dr Carter shrugged. ‘If he's not being aggressive towards you, I can't come out to see him. He's a grown man, Mr Buckley. He has to come here of his own accord.’

Mr Buckley sighed. ‘Look,’ he said. ‘Doctor. We've asked him to come down and see you, but he won't listen to us. Can't you please come out and see him?’

‘Only if he's posing a danger to himself or the general public.’

Mr Buckley rubbed his eyes. ‘Doctor. I'm not sure I'm making myself clear here. This is a situation I really struggle to talk about. But my son, Rick, who you've treated all his life, has been through a hard time lately. Ten months ago, he was beaten senseless by a total nutter and then falsely accused and arrested for rape. Since these events have happened, he's hardly left his bedroom, let alone the house. He's lost his job. He's lost contact with his friends. He's become moody and uncommunicative with his mother and myself. I'm worried about his mental health and his physical safety. I've asked him to come and see you, but, as I've already mentioned, he won't leave his room, let alone the house. So, clearly, he's suffering some form of mental illness. So, please, won't you come out and see him?’

Dr Carter blinked. ‘I'm sorry, Mr Buckley, but I can't go out and see your son on your say-so unless he's being aggressive or posing a danger. Is he being aggressive or posing a danger?’

Mr Buckley said, ‘No.’

‘Then I'm afraid I can't come out and see him. You'll have to get him to come here.’

Mr Buckley said, ‘Christ.’

Dr Carter blinked. ‘There's no need to be aggressive.’

Mr Buckley left.

Poor old Mr Buckley. He came in to the hospital to see me last night and stood with his head bowed and his hands clasped before him. He didn't speak, but I knew he was wishing me better.

Mrs Buckley never came with him. Obviously. She's dead.

Even after everything that's happened, I feel sorry for the Buckleys. All they ever did was love their son. And they used to buy me stuff for birthdays and Christmas. Mrs Buckley used to talk to me while she did the weeding in her front garden. In fact, before Jed got me too scared of axe-murderer-psycho-killers to go anywhere near their side of the square, I used to spend ages following her around and asking her questions. Unlike my father, she was never too busy to answer, and, unlike Cerys, she never shouted she was busy, Jesus, get out of my face. Sometimes, now, lying here, I wonder if I could have helped them: Broken Buckley only ever wanted someone to be kind to him, someone to make him feel better. I could have done that. I could have been his friend. Archie sees it differently. He sits and he holds my hands and I feel his thoughts flooding through me: Fucking Rick Buckley Bastard. Fucking bastard. I should have had him put away. But Archie could never have done that, because once Mr Buckley stopped talking about Broken, Archie never gave Broken a second thought. Once the novelty of his situation wore off, none of us did. We all just stopped thinking about him. We all just got on with our lives.

Then, suddenly, he reappeared.

It happened towards the end of the summer holidays fourteen months after Bob Oswald attacked him. Jed was thirteen and Skunk had just turned eleven. They had spent most of that summer holed up in Jed's bedroom playing Star Wars on Xbox, but, occasionally, they would venture out so Jed could smoke. As Drummond Square – with its four sides of houses facing in on each other – didn't have anywhere to hide his habit from Cerys (whose cigarettes he was stealing), the best place for Jed to smoke was down Shamblehurst Lane South, a long, winding overgrown path that ran from the One Stop to the train station via the Hedge End Household Waste Recycling Centre. Archie once told Skunk that the only reason the houses on the far side of the square were Housing Association and not privately owned like the rest of the square was because their gardens backed on to the Recycling Centre. Skunk hadn't known what Housing Association meant. She asked Archie to explain. He said Housing Association properties were rented dirt cheap to people who couldn't afford to buy their own houses, and the reason the planners had made these properties Housing Association was because no one in their right mind would buy a house that backed on to a rubbish dump.

Across the room, Cerys had laughed, which was unusual for Cerys. Skunk asked why she was laughing. Cerys nodded in Archie's direction and said no one in their right mind would buy a house opposite a row of Housing Association properties that could be rented dirt cheap to scum like the Oswalds.

Skunk had thought they were both talking rubbish. The dump was cool, and so was Shamblehurst Lane South. There were always loads of fallen branches to use in light-sabre battles with Jed, and people often walked their dogs there, which meant she sometimes got to pet one. It was also where she and Jed met Dillon.

He was riding his bike, but it wasn't his bike, it was a bike that had been left outside the One Stop. It was far too big for Dillon, so he was weaving all over the path. He nearly ran Jed over.

‘Watch yourself,’ Jed told him.

‘Watch yourself yourself,’ Dillon said, and then fell over. Skunk couldn't tell if he'd ripped his jeans when he'd fallen, or if they'd already been ripped. They were so big on his hips that they practically hung off his buttocks. His Calvin Klein boxers were worn like a badge of pride, as was his pale pink hoodie. Glowering from underneath it, Dillon had scraggy blond hair and bucky-beaver teeth. His skin was freckled and greasy, and his knuckles were bleeding from falling over. He held them out towards them. ‘Look what you made me do.’

Jed blew smoke out through his nostrils. ‘Didn't make you do anything. Not my fault you can't ride your bike.’

‘Not my bike. I nicked it.’

‘Stealing's bad.’ Skunk knew this. Archie had told her. Cerys had told her. And she'd been taught it at school.

‘Shut your face, dick-splat.’

‘You shut your own face, twat-head.’

‘Both of you shut your faces.’ Jed stepped closer to the bike. ‘Where'd you nick it?’

‘Just outside the One Stop.’

‘Aren't there cameras at the One Stop?’

‘Duh. That's why I put my hood up.’

Jed nodded his approval, then offered Dillon a drag on his cigarette. Dillon said cheers and took it. Skunk could tell Dillon didn't smoke much, because he didn't take it all the way back the way Jed said you were meant to: he just sort of inhaled, kept his mouth shut for a second, then puffed out a big grey cloud. Jed took his cigarette back, but Dillon's blood had stained the filter, so Jed heeled it and put his hands on the bike's handlebars. ‘Couldn't you nick one more your size?’

‘Didn't nick it cos I wanted it. Nicked it cos I could.’ Dillon wiped his knuckles on long grass. ‘Who're you, anyway?’

‘My name's Jed. And this is Skunk, my little sister.’

‘I'm Dillon,’ Dillon said. ‘Skunk's a crap name for a girl, though, ain't it? What happened? Did she stink when she was a baby?’

‘No,’ Jed told him. ‘Our mum liked Skunk Anansie.’

‘And anyway,’ Skunk said to change the subject, ‘Dillon ain't much better. Where's Zebedee and Florence?’

‘Yeah,’ Jed laughed. ‘Where's your roundabout and Dougal?’

Dillon looked from one Cunningham to the other. ‘What the fuck are you two on about?’

Jed took the bike from Dillon and tried to pull a wheelie before Skunk could admit they both watched The Magic Roundabout on Children's BBC. It was then that the bike's owner saw them.

‘Oi. You little wankers. Give me my fucking bike back.’

He was a big bloke with a shaved head. He was running towards them. His belly heaved with the motion, and his two bags of shopping knocked against his legs.

‘Give it back,’ he yelled. ‘I'll kill you.’

Before Skunk knew what was happening, Jed had climbed off the bike and was running in the direction of the Shamblehurst Barn Public House. She turned round to ask Dillon where Jed was going, but he had run off as well. In their absence, the bike remained standing of its own accord for a second, then fell over on its side. Its owner kept sprinting towards Skunk.

‘You stay where you are, you little fucker.’ His face was all red and there were sweat stains under his armpits. Skunk felt her legs turn to jelly. The man was going to kill her. She could see it in his eyes. He was going to grab her by the throat, pick her up and smash her to bits on the pavement.

Possibly he would have, but his shopping bags split before he reached her, and cans of Stella spilled all over the path. His charge towards her was halted and she turned and ran off as well. Ten minutes later, she found Jed and Dillon hiding out in the bus shelter by the train station. This is where they got to know each other. Jed told Dillon his and Skunk's ages and about their dad who was called Archie and their live-in au pair who was called Cerys. He didn't mention their mother, but, then, since the day she'd done a bunk to Majorca, nobody ever did. Dillon, in turn, told them he was a Gypsy. He was fifteen years old and this was the eleventh county he'd lived in since his mum, dad, two brothers and younger sister had all been killed in a fire started by another Gypsy who had caught Dillon's older brother having it away with his wife. Dillon had only escaped because he'd been arrested that afternoon for trying to rob a sausage roll off the deli counter in the Great Yarmouth branch of Asda. Now Dillon lived with his aunt and uncle outside the old Halfords store that had shut down the previous winter. Even though he was older than Skunk and Jed, he couldn't read or write anywhere near as well as they could, but he did have the ability to steal from a sweet counter with the shopkeeper staring straight at him, and the shopkeeper would never know. His ambition was to rob a house. Jed's ambition was to be a professional footballer. Skunk's ambition was to get married and have lots of babies and never ever leave them, so she asked Dillon back to play Xbox, which Dillon thought was cool, because all the other kids he'd met in Hedge End so far had called him a stinking pikey and left him to play on his own. As they made their way back to the Cunninghams' house, two police cars sped down Drummond Road and screeched into Drummond Square. Thinking the bike's owner had dobbed them in for stealing, Skunk turned and started to run, but Jed grabbed her by the shoulder. ‘They're not looking for us, Skunk. They're parking outside the Buckleys'.’

Skunk turned back and looked at the police cars. Mrs Willet from Drummond Primary had once got a policeman to come into school and tell them stealing's bad, but he'd come on a pushbike, so this was the first time she'd ever seen them with lights on and sirens wailing other than on the motorway. Now, close up, they were huge and gleaming and there were two policemen in each one. All four of them got out and ran towards the Buckleys'. The front door was already open and Mrs Buckley was standing under the porch roof. Her house was a giant behind her, the biggest in the square, and Archie looked at it dreamily each time he got in his car. Unlike the Cunningham place, which just had a double driveway, it was set back from the road and partially screened by swaying horse chestnuts that had recently lost their blossom and would soon start to lose their leaves. Mrs Buckley looked much the same as the trees; a tall woman with auburn hair that was greying, her face looked haggard and bloodless. She ran towards the policemen and the five of them formed a huddle. Skunk, Jed and Dillon moved as close as they dared and they listened.

‘It's my son …’

‘… his name?’

‘… Rick. Rick Buckley … he hasn't been acting himself…’

‘… have you called social services?’

‘… how long has he been like this …’

‘… you say your husband's in there with him?’

‘… please … he's my son …’

Snippets. Maddening snippets. The three children were so engrossed in the conversation they didn't notice Cerys's presence until she took hold of Skunk's and Jed's ears. The two of them were dragged back to their side of the square. In an impressive show of allegiance that made Skunk instantly love him, Dillon crossed the road to be with them. Here, they joined a swelling gaggle of neighbours and passers-by who had come out to witness the Buckleys' shame. Mrs Buckley was crying openly now. It wasn't the first time Skunk had seen an adult cry – Archie had cried after Euro 2004 and the World Cup in 2006, and Cerys cried each time another man dumped her – but it was the first time she had seen one cry the way a child cries. Mrs Buckley's face screwed up and she lost the breath that she needed to speak with. The policemen seemed scared of her emotion. They sneaked off into the house. Mrs Weston from number 12 went to Mrs Buckley and put her arms around her. Mrs Buckley sobbed in Mrs Weston's arms. The house, in contrast, stood silent.

Skunk said, ‘What's going on?’

Jed said, ‘Their son's gone mental.’

Cerys said, ‘You shut your mouth. I'll give you mental,’ and clipped Jed around the ear.

Behind them, people Cerys could not beat into silence spoke on …

‘… Poor Veronica and Dave …’

‘… it's the kid I feel sorry for …’

‘… shouldn't be out anyway …’

‘… a danger to himself…’

‘… a danger to us all…’

‘… that Bob Oswald's a bastard …’

… in hushed, excited voices that reminded Skunk of Christmas. These voices only quietened when an ambulance and two more police cars pulled up outside the Buckley house. As they tried to find spaces to park in, three of the four policemen came out with a man Skunk hadn't seen for what seemed like forever. She didn't get much of a look at him now. He was huddled with his head down and he had his hands behind his back. To Skunk, he didn't act like he'd gone mental. Sunrise Oswald at school was mental; she smoked roll-ups in the playground and called lezzer after female teachers. This man did nothing like that. He simply got in the back of one of the police cars and a policeman got in beside him. The car pulled away with its lights off and siren silent.

Really, it was quite dull.

Then Mr Buckley came out.

They didn't carry him out, but a medic stood either side of him and Mr Buckley had one arm in a sling. It looked like he had been bleeding – there was blood on his shirt and his trousers. Mrs Buckley ran to him and said, Oh David, David, but he snapped, Get off me, Veronica, and got in the ambulance without her. Again, it drove away without sounding its sirens. Mrs Buckley stood all alone on the pavement while the remaining policemen talked among themselves. Across the street, the crowd gossiped on.

‘… that's the last we'll see of him then …’

‘… I didn't even know he still lived there …’

‘… I'd almost forgotten they had a son …’

Skunk had forgotten as well. Somehow, in the past fourteen months, Broken Buckley had slipped from her mind. Sure, she and Jed had been fascinated for a short time, but then Jed got an Xbox for his birthday and Star Wars took over their worlds. She turned and looked up at Cerys. ‘What's he been doing in there?’

Cerys shrugged. ‘How the bloody hell would I know?’ ‘He's probably been murdering people,’ Jed said speculatively. ‘Like Fred West or the Yorkshire Ripper.’ The only books Jed ever read were about serial killers. He was an expert on the subject, and Skunk bowed to his superior knowledge. ‘Mr Buckley probably found a head in his fridge and asked Broken what it was doing there and that's why Broken attacked Mr Buckley. Mr and Mrs Buckley are lucky to be alive.’

‘Right,’ Cerys said. ‘That's it. Inside.’ She took hold of Skunk and Jed and ushered them up the drive. Dillon followed behind. ‘And where do you think you're going?’

‘To play Xbox.’

‘Uh-o. I don't think so.’

‘I am so,’ Dillon insisted. ‘They asked me up to play.’

‘Did they indeed.’ Cerys's tone was even frostier than normal, but remembering the way Dillon had crossed the road to stay with them earlier, Skunk stepped forward in his defence.

‘Cerys,’ she said, ‘this is Dillon. He's coming upstairs to play Xbox.’

‘No he's not,’ Cerys said firmly. ‘Bye-bye, Dillon. Off you go now, back to your mum and dad's lay-by.’

Dillon looked at Jed and Skunk for assistance, but they knew better than to mess with Cerys. He hid his face by pulling his hood up and made his way out of the square. Cerys didn't wait till he was out of earshot:

‘I don't want you playing with pikeys. They'll rob the shirt off your backs.’ She pushed Skunk and Jed into the house and slammed the door behind them. Skunk was going to tell her how Dillon had already robbed some bloke's bike, but Jed stopped her by raising his eyebrows. The two of them went up to Skunk's bedroom. Outside, the square was empty again. Jed pointed towards the Buckley house.

‘I reckon he's been killing babies.’

‘Who? Dillon?’

‘Nah. Broken Buckley. I reckon that's what the police wanted him for. They'll come back in a minute and put up a tent in the garden. Then they'll start digging up bodies.’

Skunk stared over the road. ‘There'll be TV cameras,’ she said.

‘And helicopters,’ Jed told her.

She put her hand to her bedroom window. ‘Wonder if it was anyone we knew?’

Jed shrugged. ‘The Oswalds are missing.’

‘They're at the seaside.’

‘So we think.’ Jed put his hands on Skunk's shoulders. ‘Wouldn't it be brilliant if Broken Buckley's murdered the Oswalds?’ He paused a moment, then relented. ‘Maybe not Susan Oswald. But all the others. Wouldn't that be cool?’

Skunk had to admit the idea had its attractions. Sunrise Oswald was in her form class at Drummond Primary. Skunk, like the rest of the class, had been paying her two pounds fifty protection money each week. In return for this protection money, Sunrise made half-hearted attempts to keep her sisters at bay: two of them – Saskia and Saraya – were too old for school now, but that didn't stop them hanging around the school gates and robbing pupils as they made their way home. Even worse than Saskia and Saraya, Susan Oswald often broke into the playground from the secondary-school playground next door. Protection money or not, if Susan Oswald decided to rob you, fighting back was stupid, and complaining was suicidal.

They discovered this at the start of the spring term in 2002, when Fiona Torby complained.

Fiona Torby, who had just started at Drummond Primary because her mum and dad were spending the money they had set aside for her private school fees on a divorce, complained when Susan Oswald nicked the iPod Fiona's dad had bought her to say sorry for leaving her mother. Distraught by the theft of her iPod, Fiona Torby told Mrs Willet, who, as one of the more sensible teachers, ignored her. Unimpressed with Mrs Willet and refusing to be a victim, Fiona Torby told her mother, who was already in a foul mood because her bastard husband had left her.

Mrs Torby complained to the headmaster, Mr Christy, a thin, balding dust jacket of a man who reminded Mrs Torby of her bastard soon-to-be-ex-husband. She slammed the door on her way into his office, then slammed a fist down hard on his desk. ‘What sort of school are you running here?’ she demanded. ‘You've had my happy, balanced daughter for less than a week and she's an emotional wreck already. You'd better sort this situation out, you balding little man, or I'll have your bollocks for earrings, and that's nothing compared to what the PTA will do to you once I've finished. I'll have you out of this job before you can say unfair dismissal. And you won't get another. Not after the mess you've made of this one.’

Mrs Torby made several other threats, then slammed the door on her way out. It was the happiest she'd felt in weeks. Mr Christy, on the other hand, took umbrage at being threatened in his own office, and took it out on Mrs Willet.

‘What sort of class are you running there? You've had that happy, balanced little girl for less than a week and she's an emotional wreck already. You'd better sort this situation out or I'll… I'll… I'll…’

He never actually thought of anything to do, but Mrs Willet got the picture. The Oswalds were picking on one of her pupils. She had to be seen to do something. Being an adult of more than average intelligence, she ran down the list of Oswalds she could complain to and went for the weakest one. In front of a form class of terrified Year 2 students, she called Sunrise Oswald to her desk and asked her to turn her bag out. Sunrise did so. There was an iPod in her bag. It was Fiona Torby's. Sunrise had no idea what an iPod was or what it did, but on a scouting expedition under Susan Oswald's bed, Sunrise had seen this bright and shiny thing and decided that finders were keepers.

Mrs Willet picked the iPod up. Engraved across the back were the words, Dear Fiona, just because I don't love your mother any more doesn't mean I don't love you. The music's never ending. Dad.

‘Fiona. Is this your iPod?’

Fiona Torby looked at Sunrise Oswald and remembered the way Susan Oswald had threatened to kill her if she didn't hand over her fucking iPod. Suddenly grasping the consequences of getting an Oswald into trouble – all of the Oswalds would kill her – she decided losing her iPod to the Oswalds wasn't as bad as being murdered by them.

‘No, Miss. I don't think so.’

‘Yes it is. It's got your name engraved on the back. Come up here and get it.’

Fiona Torby went up and got her iPod. Mrs Willet turned to Sunrise Oswald.

‘Do you think stealing's clever?’

‘No.’

‘Do you think stealing's big?’

‘No.’

‘Do you think it's big or clever to be a thief? Mrs Torby's ex-husband worked hard to afford this iPod for Fiona. Do you think it's fair that you just came along and took it?’

‘Nuh-nuh-no.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘No, Miss. It ain't fair.’

‘No, it isn't fair, Sunrise. It's cowardly and it's wrong and let me tell you that older children who steal get taken away from their families and locked up in horrible prisons and terrible things get done to them. Is that what you want to happen?’

‘Nuh-nuh-no.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘No, Miss. It ain't.’

Sunrise started to cry. Mrs Willet pounced.

‘Well, then, everybody. Look at the big brave thief now. Not so clever now, is she? Not so big now, is she? Sunrise, I want you to write some lines for me. A hundred lines. I want you to write, I will not be a thief. Now sit back down and stop crying.’

Sunrise Oswald sat down but she didn't stop crying. She went home in tears. Bob Oswald said, Jesus, baby, what's the matter with you? Sunrise Oswald told him. Bob Oswald said, She called you a thief? Sunrise Oswald nodded. Bob Oswald bent down before her. Honey, he said, I'm going to teach you two words now, and if anyone ever calls you a thief again, I want you to stand up straight and look them in the eye and use them. These two words are, Prove it. You get me? Prove it. You think I'm a thief? Prove it. What did I tell you to say?

Prove it.

That's my girl. Prove it. Now, give me a hug, then get me a pen and some paper. I'll write your lines out for you. Don't you worry about a thing.

The next day, Sunrise Oswald handed her lines in. Mrs Willet paled.

‘Sunrise. Come to the front of the class. Right now.’

Sunrise got up and approached the front of the class.

‘What's the meaning of this?’ Mrs Willet held the lines up. The handwriting was huge and spidery, but all the words were joined up, so it was obvious Sunrise hadn't written them. Sunrise stared at Mrs Willet.

‘My lines, Miss.’

‘You didn't write these lines.’

Sunrise folded her arms and gazed at Mrs Willet and followed her father's instructions. ‘You calling me a liar?’

Mrs Willet hesitated, then opted to sit on the fence. ‘I'm saying you didn't write these lines.’

‘Prove it.’

Mrs Willet stared. To her right, the classroom door swung open and Bob Oswald entered the room. ‘Which of you fuckers has got my little girl's iPod?’

Bob Oswald was a big man in the real world. In a room full of little desks and little people, he seemed to be a giant. His shaven head gleamed. His tattoos rippled. His smell of cigarettes and sweat pervaded. Fiona Torby stood up like she was on springs.

‘I told Miss it wasn't mine.’

‘OK, sweetie. Bring it here.’

Fiona Torby did so. Bob Oswald took her iPod from her and handed it to Sunrise.

‘There you go,’ he said. ‘And you,’ to Mrs Willet. ‘You think it's big and clever to bully little children?’

Mrs Willet said, ‘No. Of course not. But I didn't bully your daughter, Mr Oswald. I simply asked her to empty her bag out.’

‘Yeah. Right. Sure.’ Bob Oswald walked towards Mrs Willet's desk. ‘So how many other kids did you get to empty their bags out?’

‘Well, none, Mr Oswald. But I knew –’

Bob Oswald yelled before she could finish, ‘I said, how many other fucking kids did you get to empty their bags out?’

Mrs Willet shrivelled back in her chair. She said, ‘None.’

Bob Oswald leaned over towards her. ‘So. You think it's big and clever to bully little children?’

Very quietly, Mrs Willet said, ‘No.’

‘What did you say?’

‘Nuh-nuh-no.’

‘What?’ Bob Oswald leaned closer. Mrs Willet leaned back. ‘What did you say to me?’

‘No, Mr Oswald. Sorry.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Sorry.’

‘Well,’ Bob Oswald said, and a wisp of Mrs Willet's hair shifted under his breath, ‘you better be sorry. This is my little baby I'm trusting you with. You ever send her home to me in tears again, you won't just be sorry. You'll be very fucking sorry. You get me?’

‘Yes, Mr Oswald.’

Bob Oswald straightened. He ruffled his daughter's hair. ‘And you,’ he said in a harsh parade-ground bark, ‘stand up for yourself in future. Don't be so bloody soft.’

‘No, Dad. Don't worry. I won't be.’

‘Good girl.’ Bob Oswald looked over his shoulder and scowled at the petrified Year 2 pupils behind him, then turned and walked out of their world. Sadly, for Skunk, the council moved him and his family into their current Housing Association property soon after Mrs Oswald died giving birth to Sunset, and the Oswalds became the curse of her home life as well as the curse of her school life. It would not be a bad thing if Broken Buckley had murdered them all.

Now she turned to Jed and she said, ‘How do you think he'd have done it?’

Jed considered the question. ‘With a knife, or maybe an axe. Most likely with an axe, though, and I bet he slaughtered Mr Oswald first, then Saraya, then Saskia, then I reckon he'd have done away with Susan, before, finally – chop, chop - Sunrise and Sunset.’

‘But why do you think he did it?’

‘Serial killers don't have motives, Skunk. That's what makes them so difficult to catch. In fact, I bet Broken Buckley wasn't content with just slaughtering the Oswalds. I bet he's been watching you too.’

‘Jed,’ Skunk said, ‘shut up.’

‘No, Skunk. Think about it. If that's Broken Buckley's bedroom at the front there, he can see right into your room from his room. I bet that's what he's been doing since he slaughtered the Oswalds – watching and thinking and waiting. I mean, what else would he have been doing? He's been locked away in that house for almost forever. That's classic serial killer behaviour, that is – they hide away, but they're not hiding, they're watching, and while they're watching, they're working out who to kill next and what to do with the bodies.’ Jed dropped his voice to a whisper. ‘Some cut them up and store them in bin bags. Others eat them – Jeffrey Dahmer did that - and some hide them away under floorboards. There was even this one in America who turned his victims into furniture. He shot his last victim in the head and made a lampshade out of her skin. I bet you'd make a cool lampshade. I bet that's what Broken Buckley's been thinking. You're lucky he got caught when he did. Let's hope he never escapes.’

‘Jed,’ Skunk yelled. ‘Shut up.’ And then, even louder, ‘Cerys, Jed's trying to scare me.’

‘Ain't trying,’ Jed yelled proudly. ‘Doing.’

Skunk punched him on the shoulder. ‘Ain't scared of no mad axeman,’ she lied, and fled, sobbing, down the stairs.

In the hallway, Cerys was crying even harder than Skunk was. She wasn't just crying, though. She was chasing Mike Jeffries down the hallway and hurling insults at his back: Wanker. Tosser. Scum. Skunk wasn't all that worried by this behaviour. Mike and Cerys were always arguing. It was because of the things they wanted. Cerys wanted to buy a house and get married and have children. Mike didn't. Now, sick of not being proposed to, Cerys hurled her cigarette lighter as hard as she could at the back of Mike's head. It hit his shoulder and bounced back to where she was standing. Before she could grab it and throw it again, Mike yanked the door open and fled. Cerys yelled after him, ‘Go on then, fuck off. And don't even think about coming back here because I won't be here waiting. I'll find someone who loves me. I'll find someone who cares.’ Silence for an answer. Cerys curled her fists up. ‘I know you're out there, listening. I know you're not really leaving.’ The sound of Mike's car driving into the distance seemed to drain her. She spoke without looking around. ‘Go upstairs, Skunk. Go play Xbox.’

‘Have you and Mike split up?’

‘Skunk, what did I just tell you?’

‘You told me to go upstairs and play Xbox.’

‘Go on then. Bloody go upstairs. Jesus. Fucking hell.’ Cerys fumbled a cigarette into her mouth and grabbed her lighter off the floor. It fell apart in her hands. She stared at it a moment, then went through to the kitchen and slammed the door behind her. Skunk stood all alone in the hallway. She knew Cerys was crying because she could hear the hoarse sound of her tears. She sat down on the stairs and carried on crying herself. She didn't want to be killed by Broken Buckley. She didn't want to be turned into a lampshade. Even more than these things, though, she didn't want Mike and Cerys to split up. She loved Mike. He was the best boyfriend Cerys had ever had. None of the others had ever remembered her birthday or bought her presents at Christmas. Now she would probably never see him again. He would go the same way as all the other men Cerys had ever been out with. It wasn't fair. Mike was dead good-looking and dead cool and almost half good at Xbox. Secretly, Skunk had dreamed of marrying him herself when she was older. Now this would never happen. She felt deserted. Betrayed. She sat on the stairs and tried not to think about Mike or Broken Buckley. She sat on the stairs and tried to think about Dillon instead: she remembered his smile and his freckles and decided he might be the best alternative for her affections now Mike had departed the scene. She wondered when she would see him again.

It turned out to be the next day, but that would be the last time she saw him for ages.

He was running out of the One Stop with a sausage, egg and bacon sandwich in one hand and a bottle of Sprite in the other. The lady behind the counter was giving chase. Although Dillon was faster than she was, an old man with a rolled-up newspaper grabbed him by the hood of his pale pink hoodie. Dillon cried as they dragged him back into the store. Behind him, very slowly, the automatic doors slid shut. Jed and Skunk stared at the sign that was stuck there. ALL THIEVES WILL BE PROSECUTED.

Jed sighed and said, That'll teach him. Then he took Skunk home to play Xbox. Outside, it started to rain. Summer was nearly over. It seemed incomprehensible to Skunk. She didn't know where it had got to. Not knowing what else to do with the last few days of the holiday, she moped around the house while Jed tried to do six weeks' worth of homework in just under five and a half days. Skunk wished she had homework to do. Instead, all she had was the vague worry of starting her first term at Drummond Secondary School. According to Jed, older children flushed your head down the toilet on your first day while teachers stood back and did nothing. Skunk didn't want to have her head flushed down the toilet almost as much as she didn't want to be murdered by Broken Buckley. She sat at her bedroom window and stared out on the street. Today, it was very quiet. It was never usually so quiet but every summer the Oswalds went to live by the seaside and have a good time. Skunk wished her family could go and live by the seaside every summer and have a good time. She phoned Archie on his mobile and asked him why they couldn't. He said it was because he had to work to keep a roof over their heads. Skunk said, Doesn't Mr Oswald have to work to keep a roof over their heads? Archie said, morosely, That lazy bastard's on benefits, Skunk, so doesn't have to struggle like we do. Now bog off. I'm trying to work.

Skunk hung up and returned to staring out the window. Across the way, life seemed to be back to normal. Mrs Buckley was on her hands and knees in the front garden and Mr Buckley's car wasn't on the driveway, so he was most likely at work. Skunk didn't know where Broken was. Jed had several theories: A, he was in an asylum; B, he had been locked up for murdering babies; C, he had been locked up for murdering babies, escaped, and was now living rough in the fields behind Botleigh Lakeside. Skunk wanted to go over and ask Mrs Buckley where Broken had got to, but was put off by Jed's theory D: Broken had been locked up for murdering babies, escaped, and was now being sheltered by Mr and Mrs Buckley who – in a desperate attempt to keep him from butchering them in their sleep – were keeping him supplied with eleven-year-old girls to be slaughtered and turned into lampshades.

In truth, Broken Buckley was sharing a small room in a secure unit with three other men who were broken the same way Broken was broken. Each day a male nurse would inject him in the left buttock and he would lie down and drift off to sleep. Or stare. Or sob. In the evenings, Mr and Mrs Buckley would phone the centre and ask to speak to Rick. As the phone was in the residents' common room, quite often, nobody answered. On the few occasions when somebody did answer, he or she failed to grasp they were using a phone. They picked it up, they stared at it, then let it drop and shuffled away. The mouthpiece hung limp on its cord. Hello? Hello? Hello? Eventually, Mrs Buckley would crack and hang up. She would turn her back on her husband. She would sob in the palms of her hands. Mr Buckley would stand helpless beside her. At night, they would lie in bed without speaking and worry themselves sick about Rick. How was he doing? How was he coping? Was he being well fed? Mrs Buckley imagined him sobbing. Mr Buckley imagined him slowly getting better as psychiatrists and social workers discovered the things that were wrong in his head. Please, he kept thinking, please let them discover the things that are wrong in his head. Mr Buckley had tried to do this himself after his trip to see Dr Carter, but it had proved to be beyond him. ‘Son,’ he would say on the landing outside Broken's bedroom door. ‘Son? Can I come in? Can we talk?’ No answer. Mr Buckley would rattle the handle. The chair on the other side would hold firm. ‘You can't stay locked away in there forever,’ Mr Buckley would say. ‘You'll have to come out in the end.’

No answer. Never any answer.

Never any response at all.

One time, Mr Buckley retreated down the stairs and waited. At 3 a.m. the following morning, his patience was finally rewarded when Broken shuffled out of his bedroom and made his way down to the kitchen. Mr Buckley stood in darkness and watched his son make his way to the fridge and stand with his hands pressed flat against its white surface. Broken stayed that way for a long time, then quietly pulled the door open and began to pick from the plate of food Mrs Buckley had left there in the hope he would come down and eat it. In the yellow glow of the fridge light, Mr Buckley felt sick at how pale his son was and the scratch marks on his face and his arms. Oblivious to the fact he was being studied, Broken continued to eat. A cold sausage, a boiled egg. He drank milk. After a few minutes, the cool refrigerated air began to remind him of fresh air, and this, in turn, reminded him of the day Bob Oswald attacked him. No longer hungry, Broken dropped the ham sandwich he'd been eating and pushed the fridge door shut. He put his hands to his face. Inside, whispered, breathless, he said, over and over, I feel dirty, I feel dirty, I feel dirty, but he didn't make any sound. In contrast, Mr Buckley said, ‘Son?’

Broken froze at the suddenness of the voice. A sick giddiness swept through him. He said nothing, did nothing, was still.

‘Son,’ Mr Buckley said. ‘It's OK. I just want to talk to you. That's all I want to do.’

Broken stayed huddled in darkness. Behind him, out of more darkness, Mr Buckley said, ‘I just want to know how you are. That's all. I just want to know how you're doing.’ His voice was shaking. He didn't know why. It was only his son he was talking to. Mr Buckley stepped forward. ‘Son, please. Just tell me. What's going on in your head? Why are you hiding away in your bedroom? Is there anything I can do to help? Is there anything anyone can do to help? Anything at all?’ He took another step forward. Broken didn't hit him. He just screamed and flung his arms out. Mr Buckley jumped back and banged his hip against the work surface. A cup rolled off the edge and smashed to bits on the floor. Above their heads, there was the sound of sudden movement, then Mrs Buckley came running down the stairs and into the kitchen.

‘What's going on?’ She switched the light on. ‘Rick?’ she said. ‘Rick? Are you OK? Is everything OK?’ She held her arms out and stepped towards her son. He screamed in her face and pushed her away. Mrs Buckley stumbled backwards. Broken ran past her. His footsteps pounded the stairs. His bedroom door slammed. Silence fell. Mr and Mrs Buckley stood helpless within it, he with shards of china glittering all around him, she staring at the half-eaten sandwich Broken had dropped on the floor.

Finally, she said, ‘He was eating, David. He was eating. You know how little he eats these days. Why couldn't you leave him alone?’

‘We've left him alone for too long, Veronica. Look at the state he's got into.’

‘He is not in a state. He's going to be fine.’

‘He is not going to be fine. How can you say that?’ ‘Because, David, he is.’ Mrs Buckley picked the ham sandwich off the floor and fed it into the waste disposal unit, then went back up to bed. Mr Buckley used a dustpan and brush to throw the shattered cup away then went upstairs to join her. The two of them lay together, alone, and stared into darkness from different directions. Neither wished the other goodnight.

The next day, Mr Buckley stayed up again, but Broken remained in his bedroom. And the next day. And the day after that. Scared that his son was starving to death, Mr Buckley tried to get into his bedroom once more, but a chair remained wedged between the floor and the handle. As Mr Buckley pushed and pushed against it, Broken lay on his side with the knife he had taken from the kitchen soon after Bob Oswald attacked him. He held it in a tight, sweaty palm with the blade rising up at an angle. Sometimes, he pointed this blade towards the window. Sometimes, he pointed it towards the door. Other times, during the worst times, he turned round and round in a circle, because he was frightened of being attacked from behind, without warning, but couldn't see all ways at once. Broken was always afraid now. He couldn't make sense of it all. He had only been washing his car. Why had Bob Oswald attacked him? Broken didn't know, Broken couldn't imagine, so he clutched his knife and lived in fear of Bob Oswald while, outside, Mr Buckley tried to get into his room.

‘Son? Son? Open this door. I'm not going to hurt you. I just want to know how you are. Please, son, please. I'm worried sick about you. Your mother's worried sick about you.’ Mr Buckley stood back. He shook his head. Mrs Buckley was standing behind him. She said, ‘You'll have to go back to the doctor.’

‘What's the point in going back to the doctor? Carter's useless. A bloody fool.’

‘Yes. I know. But you'll have to go back to him, David.’ She nodded towards the shut bedroom door and dropped her voice to a whisper. ‘I don't think he's eaten in days.’

‘I know that, Veronica, I know that, but I don't think starving yourself to death constitutes aggressive behaviour, do you?’