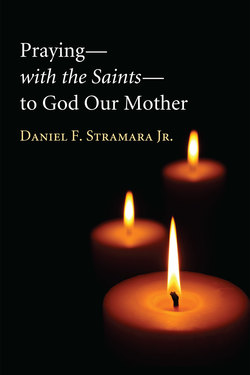

Читать книгу Praying—with the Saints—to God Our Mother - Daniel F. Stramara - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеLet the word of Christ dwell in you abundantly,

as you teach and admonish one another in all wisdom,

singing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs,

with gratitude in your hearts to God.

—Colossians 3:16

About the Topic

God is a wondrous life-giving mystery to be experienced personally. The rich bounty of God’s love overwhelms us and defies scrutiny. No matter how much we try to comprehend God, totally understand God, we can’t; we can only partially know God. The Scriptures, as well as Christians throughout the centuries, have warned against putting God in a box, making images of God and turning them into idols. No one image can capture the infinite graciousness of God’s total presence; no one metaphor can exhaust the immeasurable liberality of God’s complete loving presence (known as “immanence”). That is why the Scriptures abound with various analogies and metaphors, struggling to paint a comprehensive picture of God’s loving relationship with us. Genesis tells us that God created us in the image of God, male and female God created us. Appropriately, Moses and the prophets after him were not afraid to compare God’s love for us to that of a mother for her child, or to utilize other feminine analogies and metaphors. The Scriptures, as well as Christian tradition, emphasize that God is neither male nor female, that the infinite Divine Nature cannot be circumscribed by such categories pertaining to finite nature. God’s very Being transcends these attributes and surpasses their richness while at the same time encompasses them.

Masculine metaphors of God afford us deep and beautiful insights into God’s inexhaustible love for humanity. The majority of us are quite familiar with these. Unfortunately, the Christian populace is not as aware of the feminine imagery employed by the Scriptures as well as Christians throughout history, providing yet another window into the vastness and enduring strength of God’s relationship with us. God is neither male nor female, but possesses qualities we deem as masculine and feminine, while at the same time surpassing such life-giving qualities. Regrettably, for us humans, we usually come into consciousness about something only when we really concentrate on it, and thus end up possibly excluding other vital realities. This book runs that risk. I have purposely focused on feminine analogies and metaphors of God and not masculine ones. However, as will be evident, the two are not exclusive. Many writers, both biblical and Christian, felt quite at ease moving back and forth between masculine and feminine imagery.

About the Purpose

The purpose of this book is to enable one to experience and to appreciate in a prayerful and meditative manner various feminine aspects of God. While this book is primarily a book of prayer, it can also be used by the serious scholar as an anthology of scriptural and Christian texts depicting God in feminine imagery; Appendix B lists the critical sources used in the translations.

It is my express hope that Praying—with the Saints—to God Our Mother can enrich your personal life and encounter with God, as well as bear fruit in Christendom as a whole: secular and religious, lay and academic, as well as within the various Christian churches and traditions.

The purpose of this book is to promote a healthy spirituality that embraces both the masculine and the feminine qualities of God. However, by its very nature, Praying—with the Saints—to God Our Mother emphasizes the feminine aspects of God, but not to the exclusion of the masculine. While honoring the masculine, it celebrates the feminine. Furthermore, femininity is far broader and richer than just motherhood. In this book are images of God as a woman who is sister, friend, teacher, guide, architect, baker, and so forth. Likewise God is depicted in female animal form: she-bear, leopardess, lioness, hen, mother bird, as well as other living creatures.

About the Format

Because I wish this book of prayer to be ecumenical I have chosen to use the format of prayer and meditation that predates all divisions within the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic faith. The structure is that of “monastic” prayer, commonly known as the Liturgy of the Hours. I in no way intend this book to replace the Liturgy of the Hours as used within the Roman Catholic Church or Orthodox Office of Readings; rather, it is to serve as a complement. Early Christian men and women assembled together to pray the Psalms, meditate on the Scriptures, and draw inspiration and encouragement from other writings and songs composed by recognized spiritual authorities.1 This was regularly done in the morning and evening of every day. For biblical witnesses to the regular practice of Christian prayer see Luke 11:1–13 & 18:1–8; Ephesians 5:18–20 & 6:18; Colossians 4:2; and 1 Thessalonians 1:2 & 5:16–20. Quite often prayer was done at home (Acts 2:46; 10:9; 12:5, 12). Those men and women who withdrew into the desert in imitation of Jesus, escaping the distractions of the world in order to focus upon God, eventually gave concrete form to this method of prayer and reflection. The morning was devoted to pondering how the Law, Prophets, and Writings prepared the way for the New Covenant revealed in Jesus Christ. Thus the scriptural texts chosen for the morning office in this book are usually taken from these books. The evening prayer celebrates the riches bestowed on us by God Almighty through the Word of God in the Holy Spirit. Consequently, the biblical texts are regularly drawn from the New Testament. In each office of prayer, three or more psalms were recited, usually chanted from side to side. A canticle was also sung. This structure is followed throughout the book. For those who have used the Liturgy of the Hours or other books for the Divine Office, you will only have to flip to the front of the book to find the indicated psalm and scriptural reading. The song, known as the “canticle,” is up to you. Everything else is printed in sequence except for the standard format for Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, which is provided at the very end of the book. You will also have a choice of a doxology to use (see below).

About the Content

The vast majority of modern English-speaking Christians read translations of the Psalms based upon the original Hebrew. However, for over fifteen hundred years this was not the case. Early Greek-speaking Christians used the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, known as the Septuagint (abbreviated as LXX). In fact, nearly 97 percent of all the quotations in the New Testament from the Law, Prophets, and Writings were taken from the LXX, not from the original Hebrew. To this present day, the Septuagint version of the Bible is the official text used by Christians who call themselves Orthodox. In the West, the Scriptures were quickly translated into Latin; this version was naturally based upon the Greek. This Old Latin version of the Psalms was popular and survived in various renditions. Consequently, it is the Greek version of the Psalms which has been prayed by Christians, both East and West, for nearly nineteen hundred years, except for those Christians from the sixteenth century onward known as Protestants who used translations based on the Hebrew Bible. The purpose of the book is to recapture the experience of previous generations of Christians who recognized the feminine aspects of God. Most of them prayed and meditated upon the Greek version of the Psalms, and thus I have purposely chosen to make my own translation of them from the Septuagint. The Psalms will thus follow that numbering. Besides, this will provide you with variety in your prayer life.

The Scriptures play a vital role in the life of every Christian. The books of the Bible are authoritative and consequently authoritative translations were made. The Jews refer to their own Hebrew Bible as the Tanak, standing for Torah (Law), Neviim (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). I will refer to the Hebrew Bible as the Tanak (abbreviated TNK) and all translations based upon this version will be noted as such. As already mentioned, the authoritative Greek version of the Bible is called the Septuagint, meaning “seventy,” abbreviated using the Roman numeral (LXX). The same applies to the Latin Vulgate (abbreviated VULG), the authoritative Bible in the Western Catholic Church. There is one other ancient authoritative version of the Bible that I have used, the Syriac, known as the Peshitta (PESH). The Peshitta is an Aramaic/Syriac translation of the Tanak and the Greek New Testament. It is authoritative among Syriac-speaking Christianity and churches that developed out of Antioch. Where I have made my own translation from the New Testament Greek and I wish you to use my version, the passage is followed by NT. If no abbreviation follows a scriptural reference it means you are to use whichever translation you prefer.

Christians consider certain books to be canonical, or authoritatively binding, thus forming the Bible. I, myself, am a Catholic Christian. Some quotations will be from books not found in the Protestant Bible. However, I am not attempting to impose my own beliefs and persuasions upon you, the prayerful reader. What I am trying to do is present the experience of all Christians in their encounter with God before the Protestant Reformation. Catholics have more books in their Bible than do Protestants; Orthodox Christians have even more. Thus I have chosen to use the largest canon of the Bible, that belonging to Orthodox Christianity. For the Protestant reader, these extra books are known as the Apocrypha, and are considered merely inspirational. For the Catholic reader, the extra books you will encounter are known as “extra-canonical.” For Catholic and Orthodox Christians, equal authority resides in the Scriptures and the Apostolic Tradition. For Catholics, the extra-canonical books, nevertheless, form part of the Church’s Tradition.

Case in point: one scriptural reading is taken from 4 Esdras, a book not considered canonical by any church but for centuries (even still) included in the Latin Vulgate after the New Testament. This book was quoted by numerous early church authorities such as Clement of Alexandria, Cyprian, Tertullian, Commodianus, Ambrose, Athanasius, and Gregory of Nyssa (known by Catholic and Orthodox Christians as Fathers of the Church).2 Several extracts from 4 Esdras were incorporated into the Roman Catholic Liturgy.3 In fact, a verse from this book persuaded Columbus and his royal sponsors that there was land to be discovered west of the Atlantic. Fourth Esdras has impacted Western civilization in numerous ways.4

I have also chosen to use one text found in 1 Enoch. Perhaps this extra-canonical book is more familiar to Christians. The New Testament epistle known as Jude contains a direct quote from it and mentions Enoch by name. This book forms part of the canonical Scriptures of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians. First Enoch was also used at Qumran and is found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Besides Jude 14–15 being a quotation from 1 Enoch 1:6, verses 6 and 16 of Jude are also influenced by it. Understandably, many early Church Fathers considered 1 Enoch inspired and meditated upon it, for example, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Origen, Clement of Alexandria, and Tertullian.5 First Enoch, as well as other biblical books not found in the Tanak but used by Christians throughout the world and throughout the centuries (i.e., Apocrypha), are employed as sources for passages in both Morning and Evening Prayer.

A regular part of the Liturgy of the Hours is a time for meditation upon a passage written by some spiritual authority. The question of authority can be a sticky issue. I have chosen to quote in the Liturgy of the Hours only passages taken from the Fathers of the Church and saints recognized by the Catholic Church. A word of explanation is in order. In 1 Corinthians 11:1 the Apostle Paul exhorts, “Take me for your model, as I take Christ.” Elsewhere Paul states, “Take as your models everybody who is already doing this and study them as you used to study us” (Phil 3:17). Christians are to emulate other Christians who have more fully conformed their lives to Christ than we have (see also 1 Thess 1:6–7; 2 Thess 3:7–9; Heb 6:12 and 13:7). Eventually, the issue arose of deciding who ought to be held up publicly as a model of Christian virtue and teaching. The Roman Catholic Church, of all the catholic apostolic churches, over time devised a method and system for deciding who is worthy of such a widespread status. Every Christian is called to be a saint, but in certain people the splendor of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit more brightly shine. I have chosen to use writings from those Christians who have been sanctioned by the Catholic Church. There are three ascending levels of Catholic sainthood: Venerable (Ven.), Blessed (Bl.), and Saint (St.). The names of the men and women quoted herein will be preceded by their recognized Catholic title and position.

However, a few saints will also be quoted who are not formally recognized as such by the Roman Catholic Church. Originally there was one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church. This body of Christians became divided in the fifth century into two major camps: the “new” Oriental Orthodox Churches and the original Catholic Orthodox Churches. Eventually there was another split, a schism between East and West in the eleventh century, resulting in the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Churches. Over the centuries, various non-Roman Christians sought communion with the Church of Rome; these have formed what are known as the Eastern Catholic Churches. The Roman Church is only one of more than eighteen Catholic Churches in communion with the bishop of Rome, who is known as the pope. Because all the Catholic Churches in communion with the bishop of Rome recognize the various Orthodox Churches as fully apostolic and preserving the catholic faith, men and women who are regarded as saints in these particular churches will also be quoted. One such illustrious (Greek) Orthodox saint is Gregory Palamas. His spiritual authority and learning in Orthodoxy is comparable to that of St. Thomas Aquinas in the West.

Vatican II has this to say regarding the teachings of the Orthodox Church: “In the study of revealed truth, East and West have used different methods and approaches in understanding and confessing divine things. It is hardly surprising, then, if one tradition has come nearer to a full appreciation of some aspects of a mystery of revelation than the other, or has expressed them better.”6

Because of the length of this book, quotes from non-canonized Christians—whether they are Catholic or Orthodox, as well as Protestant—will be found in a forthcoming book. Many would expect to find excerpts from Dame Julian of Norwich in this volume; however, she has never been canonized by the Catholic or Orthodox Churches and thus her texts are not included in this book. Reformers such as Luther, Calvin, and Zinzendorff, not to mention other Protestant renowns, also used feminine metaphors when speaking about God. As should be evident by now, and as will become strikingly clear later, Christians throughout every century and belonging to every church affiliation have celebrated the feminine aspects of God. Meditational passages in this book have been drawn from eight non-canonized but officially recognized Fathers of the Church, thirteen authoritative church documents (five of which are from Ecumenical Councils), and seventy-five Catholic and Orthodox saints speaking almost every language, and spanning every century. In Appendix A you will find a complete chronological list of these Fathers, documents, and Catholic/Orthodox saints.

One further point needs to be made. Saints are noted for conforming their lives to Christ under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit to the glory of God Almighty. The Catholic Church also accords various extra titles to certain saints for their teaching authority. Listed according to importance, we have Apostolic Fathers (those who lived and taught from AD 70–125), Post-Apostolic Fathers (AD 125–175), Fathers of the Church (AD 175–787), and Doctors of the Church, who are outstanding teachers acclaimed as authorities. Some Fathers of the Church are also Doctors, thus possessing the highest honor. But one need not live before 787 to be a Doctor of the Church, nor must one be a man; there are three female Doctors of the Church: Sts. Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Avila, and Thérèse of Lisieux. In the Catholic Church there are thirty-three Doctors.7 Every single one of them utilized feminine imagery to express a facet of God’s infinite love.

Finally, there is the peculiar case regarding St. Gregory of Nyssa, who was highly influential during the Second Ecumenical Council, known as Constantinople I. For some reason, he is not yet acclaimed by the Roman Catholic Church as a Doctor of the Church, even though he is a weighty and brilliant authority whom the Seventh Ecumenical Council hailed as the “Father of the Fathers.” Two Eastern Catholic Churches in communion with Rome acknowledge Gregory of Nyssa as a “Doctor of the Church”: the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Chaldean Catholic Church. Because the Seventh Ecumenical Council, recognized by Rome, as well as two Eastern Catholic Churches, accord Gregory of Nyssa the title of Doctor of the Church, I have likewise, thus raising the number by my reckoning to thirty-four Doctors.

I have used authors sanctioned by the Catholic Churches as well as Orthodox to demonstrate that speaking about God in feminine terms is not contrary to the Catholic Church’s Tradition. In fact, it is part and parcel of the Apostolic Tradition as demonstrated by several authors included herein. Authors will be followed by the date of their death so that one can appreciate the persistency and continuity of this tradition.

About the Translations

One of the most difficult jobs is to translate accurately from one language into another. All translations are my own and are based on the most critical text available, unless noted otherwise. While I am concerned with the authenticity of the text in question and the historical meaning the author most probably had in mind, I am more intent upon presenting the possible historical perception that the Christian community had when pondering these texts. This is especially true for the Psalms, which were prayed in a christological context. I have striven to be faithful to the actual wording and to maintain any vagueness that might have permitted an alternate understanding of the text. For example, the Hebrew version of Isaiah 46:3 is polyvalent, that is to say, open to various interpretations. It reads:

Listen to me, O House of Jacob,

and all the remnant of the House of Israel,

whom I have borne since your conception,

whom I have carried since you were born.

The Hebrew does not make it explicit if God “carried” Israel internally or externally. Because the passage is open to a feminine interpretation—God carrying us within God’s own womb—I have used this passage. It could legitimately be heard in this fashion. Such a contention is verified by the Vulgate. When Jerome translated this text he explicitly brought out the feminine possibility in his Latin translation:

Listen to me, O house of Jacob,

and all the remnant of the house of Israel,

you who are carried by my uterus [meo utero],

you who are borne by my womb [mea vulva].

I have always attempted to be faithful to the original wording. However, sometimes I felt some modifications to be necessary for flow in the English language.

1) The Psalms were originally written as poetry to be sung. Accordingly, I have tried to maintain some semblance of meter, rhyme when appropriate, plays on words and the like. To do this, at times it was necessary to add an adjective or adverb so that the beat could be facilitated in public recitation. In all cases, what I perceive to be the meaning of the text was never violated. Reputable translations were always consulted. Some admirably captured the beauty of a turn of phrase, or the full force of a verb. I am indebted to their insights and sometimes a wording has been borrowed, not out of plagiarism, but out of praise for the translator. In the final analysis there are only so many ways in which a sentence can validly be translated. Biblical translators can appreciate my predicament.

2) Unlike English, nouns in most languages have a grammatical gender: masculine, feminine, or neuter. Verbs likewise take corresponding feminine and masculine endings. Some nouns are grammatically masculine but can refer to either sex of an animal, or some are feminine. Case in point: Isaiah 31:5 refers to birds that are hovering. The noun is grammatically feminine in the singular but becomes masculine in form when plural. In the following verse the verb is in the feminine plural. The verb means “to hover” (especially above a nest); thus I chose to bring out the validly possible feminine metaphor:

Like mother birds hovering over their young

Yahweh Sabaoth will shield Jerusalem;

to protect and save,

to spare and deliver.

But in order to do this, I needed to add the word “mother” to convey the underlying feminine grammatical, as well as metaphorical, text. God being compared to a mother bird is common in the Scriptures.

Also because certain nouns are feminine, this permitted the original authors to create images revolving around women. For example, the word for “wisdom” in Hebrew (as well as in Greek and Latin) is feminine. When Wisdom is personified it is presented as a woman. Many of us are familiar with such passages, especially from Proverbs.

In Hebrew, the word for “spirit” is also feminine. I have not utilized every text in which “spirit” is grammatically followed by a feminine adjective or verb with a feminine ending. However, I have chosen to garner some texts so that the reader can experience how many Aramaic- and Syriac-speaking Christians considered the Holy Spirit to be feminine, inasmuch as they considered God masculine. (Jesus spoke Aramaic.) Recall that God, in and of God’s self, is actually neither male nor female. This grammatical feminine gender of the Spirit allowed Christians to depict the Spirit as mother.

3) Sometimes the richness of a particular word needed to be brought out by more than one word in English. One such word is the Hebrew rachemim, usually translated as “compassion” or “mercy.” Its root is the noun rechem, which unequivocally means “womb.” Thus, in certain passages wherein I believed the context warranted it, I translated rachemim as “maternal compassion.” In fact, Hebrew has five other words for compassion, pity, or mercy. The underlying womb motif in rachemim should not be overlooked. In the famous scene where Solomon must decide to which of two women a certain baby belongs, he purposely proposes to have the child divided in half. He discerns which woman is the true mother by the one who has pity or compassion (rachemim), in other words, the one whose womb is moved for her baby’s welfare. This is lost upon the English reader. In the following text, once again from Isaiah, the feminine imagery is explicit; thus this passage has been used by many. But the richness of the maternal nature of God is missed when rachemim has been translated merely as “pity” or “mercy.”

For Yahweh comforts his people

and displays maternal compassion on his afflicted ones.

Zion was saying, “Yahweh has abandoned me;

the Lord has forgotten me.”

Can a mother forget the baby at her breast,

feel no maternal compassion for the child of her womb?

Even should she forget,

I will never forget you. (Isa 49:13–15)

4) Perhaps nothing is more challenging than the very terms used to refer to God. The Hebrew for “God” is elohim. This noun is actually a plural form, literally “gods,” and at times it is used to refer to the gods of the heathens. However, whenever it refers to the One God of Israel the verb is almost always in the singular, except, for example, in Genesis 1:26—“God said, ‘Let us make man in our own image . . .’” While the grammatical form of elohim is masculine plural, it is theologically understood as singular and thus grammatically followed by the verb in the masculine singular. However, the grammatical singular of elohim is eloah, which is feminine. In one sense, elohim is the perfect word for God because it displays and contains within itself the plurality of the masculine and the feminine. It is plural and yet singular, masculine yet feminine. The term eloah appears several times in the Scriptures and is always followed by the verb in the masculine singular. Scholars believe that rectification of elohim and eloah to be followed by a masculine singular was a conscious act on the part of the copyists who transmitted the written text. However, there is one instance in which the Hebrew text has kept eloah followed by a feminine direct object. It is Job 40:2, “Will the one who contends with Shaddai correct? Let the one who accuses Eloah answer her.” Because in the ears of any Semitic speaker eloah is clearly a feminine noun, possessing the feminine ending, I have chosen not to translate it as “God” but keep it in its original Hebrew/English spelling. I am intending it to carry a feminine aura. Such an intention can be argued when it is realized that the author of Job regularly used eloah in parallel with shaddai, another puzzling term.

Shaddai as a name for God is most ancient. English Bibles, following the Septuagint translation, render it as “Almighty.” Scholars still debate its actual meaning; thus I have not resolutely concluded that shaddai has the feminine meaning I attach to it, but in this book of prayer I am underscoring that valid possibility. Early on, scholars believed that el shaddai meant “God of the Mountain.” However, Albright in 1935 pointed out that the Hebrew word shad means “breast,” and that in the mind of the ancients, a mountain rising up from a plain resembles a breast mounted above the abdomen.8 Having known this, and read other scholarly references arguing that on linguistic grounds el shaddai possibly means “God the Breasted One,” I did my own contextual analysis of the divine name. I was struck at how many times el shaddai is used in a context referring to the blessing of fertility (see Genesis 17:1–22; 28:1–5; 35:8–12; 43:14; 49:25 as well as Ruth 1:1–22 where this blessing was lacking). Of particular interest is the explicit avowal that el shaddai bestows “blessings of breast and womb” (Gen 49:25). Naturally, God the Breasted One would grant such graces of fertility. I mention this because my own independent research was confirmed when I read a scholarly article by Cross.9 He too believes, because of linguistic and textual analysis, that shaddai can validly be interpreted to mean “breasted one,” and was understood as such by the early Hebrews. Of further interest is the contention by Walker that shaddai comes from the Akkadian word shagzu and was an epithet for the god Marduk meaning God the Womb-Wise, or God the Midwife.10 Whatever the case may be, understanding shaddai as a feminine name for God is neither unreasonable nor without scholarly support. This feminine nuance is further strengthened when it is paralleled with eloah. This cannot be mere coincidence. Consequently, I have rendered the Hebrew for shaddai in English and at times followed it by “God the Breasted One.”

Finally, a word should be said about the psalms I have chosen. I have purposely utilized psalms that address God as “you,” or ones in which God speaks in the first person. Because I am pondering the feminine side of God, I felt it inappropriate to use psalms that constantly refer to God as “he.” I, personally, have nothing against referring to God as “he,” but thought that this would be distracting in this context. Nevertheless, some readers might be disconcerted that on occasion “he, him, and his” are found. I must be faithful to the original text. Furthermore, the ancient authors, whether biblical or Christian, felt quite at ease employing both analogies at the same time. I have respected their experiences and practices. Other normal rules of non-gender biased translation have been followed, such as avoiding unnecessary “he who has” and related phrases, replacing it with “anyone” or “whoever.” I refer the reader to such gender-inclusive translations of the Scriptures as the New Jerusalem Bible, the Revised New American Bible, and the New Revised Standard Version. Inevitably, I will not please everyone, but I have chosen to be grammatically accurate and faithful to the original wording and meaning of the texts, without being slavishly so. Any errors or oversights are my own.

About the Doxology

In the early church there were a variety of doxologies; eventually “Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit . . .” became standard. St. Basil the Great († 379), a very important Doctor of the Church, argued that there were various ancient doxologies and that these were legitimate.11 Because a doxology must be used in the Liturgy of the Hours, I needed to address the issue of coming up with an alternate to the canonical doxology that brings out the masculine side of the relationality within the Holy Trinity. Proposed doxologies such as “Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier” are unacceptable from a Catholic/Orthodox point of view because 1) they do not safeguard the relationship among the divine Persons within the Trinity, 2) each of the Persons is Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier, and 3) such a doxology only emphasizes God’s relationship with us and not God’s eternal nature as the Divine Community of Love.

However, it is important to note that Fathers and Doctors of the Church gave voice to their praise of God in terms beyond the traditional “Glory be.” St. Theophilus of Antioch was the first to use the term “Trinity” around AD 180. The text is Ad Autolycus 2.15, in which he has “God, His Word and His Wisdom.” The relationality is preserved but in English the possessive pronoun is masculine; see also Clementine Homilies 16.12 where Spirit is also feminine Wisdom. St. Gregory of Nazianzus

(† 389), a Doctor of the Church who was acclaimed as “the Theologian” by the Orthodox Church, praises God as “Mind and Word and Spirit, one in relationship and divinity.”12 Such a doxology is appealing to me because it is gender neutral. However, the metaphors are intellectual and abstract. Furthermore, for a book of prayer such as this, the feminine side of God should be celebrated in the doxology. In fact, St. Aphrahat († ca. 345), another Father of the Church, wrote: “Glory and honor to the Father and to his Son and to his Spirit, she who is living and holy; let the mouths of everyone render praise, above and below, for ever and ever, Amen.”13 Such a conception in the Syrian Church is refreshing. Nevertheless, as shall be seen, the Doctor of the Church St. Ephrem the Syrian († 379) depicted all three divine Persons as feminine. Moreover, according to the Ecumenical Councils, all three Persons are equal; whatever is ascribed to one is equally ascribed to the other, except for their terms expressing origin of relationship. If a doxology is to be truly theologically balanced, all three Persons must be equal, i.e., all three masculine, or all three feminine, or all three neuter.

Thus after the section of the Psalms and Scriptures you will find a list of possible doxologies you can employ, many based off of early church writings and some created by myself. In no way is this list to infer that I consider the traditional doxology as incorrect or theologically problematic; the issue is, however, pastoral. It will be up to the reader or praying community to decide which form will be used. If Praying—with the Saints—to God Our Mother is used publicly, I suggest that the first line of the doxology be recited only by the one leading the prayer; the refrain “as it was in the beginning

. . .” can be a communal response, thus avoiding confusion concerning which wording is being adopted. Of course, one is free to alternate the various doxologies between the morning and evening office or after each psalm.

May this book of prayer and meditation deepen your relationship with the God of our ancestors, and may She abundantly bless you as you prayerfully ponder another rich and life-giving facet of the Holy Trinity.

Stand firm, then, brothers and sisters,

and maintain the traditions that we taught you,

whether by word of mouth or by letter.

—2 Thessalonians 2:15

You must remain faithful to what you have learned and firmly believe;

knowing full well who your teachers were,

and how, ever since you were a child,

you have known the Holy Scriptures—

from these you can learn the wisdom

that leads to salvation through faith in Christ Jesus.

All Scripture is inspired by God

and useful for instruction and refuting error,

for guiding people’s lives

and teaching them to be upright.

This is how someone who is dedicated to God

becomes fully equipped and ready for every good work.

—2 Timothy 3:14–17

1. For a good survey of the history of Christian prayer see Taft, Liturgy of the Hours as well as Uspensky, Evening Worship.

2. See Myers, I and II Esdras, 131–34.

3. See Stuhlmueller, “Apocrypha,” 1:552.

4. See Metzger, “Fourth Book of Ezra,” 1:523.

5. See Isaac, “I Enoch,” 1:8.

6. Vatican II, “Decree on Ecumenism,” §17, p. 466.

7. According to reports coming out of Rome, Pope Benedict XVI will declare Hildegard of Bingen a Doctor of the Church in October 2012. When this happens, she will be the fourth female Doctor of the Church.

8. See Albright, “Names Shaddai and Abram.”

9. See Cross, “Yahweh and the God of the Patriarchs.”

10. See Walker, “New Interpretation.”

11. See Basil of Caesarea, De spiritu sancto 1.3 & 29.71 (PG 32:72B–C & 200B–201A).

12. See Gregory of Nazianzus, Oratio 12.1 (PG 35:844B).

13. See Aphrahat, Demonstrationes 23.61 (PS 2:128).