Читать книгу Japanese Throwing Weapons - Daniel Fletcher - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеShuriken-jutsu

For nearly a thousand years, there have been schools in Japan dedicated to the art of killing. The ancient schools of martial arts instructed students in every facet of survival in a hostile environment, including castle design, first aid, stress management, and more. The martial arts we see so often these days bear only a vague resemblance to their true origins. There is nothing wrong with using parts of budo in order to teach virtues, morals and physical fitness, but there are much more serious kinds of teachings that exist in the ancient densho (written records) and kuden (personal transmissions) of the original schools. Most people have no idea of the serious nature of real budo. While it is perfectly understandable that your average parent would not want his or her child actually learning how to kill, it must be understood that these arts were not created for the purpose of entertainment or for sport or for self-improvement—they certainly were not intended for children. The martial arts were intended to train soldiers in how to do their jobs, just as modern militaries train their recruits in the use of the rifle, bayonet, and grenade. The purpose of this book is to introduce you to the teachings of only one small piece of that life-and-death world of budo.

The word shuriken (shoo-ree-ken: The Japanese “r” sounds like a soft “d”) is a Japanese term for small pieces of metal used as throwing weapons. They appear quite often in films and on TV, so it’s unlikely that anyone would not recognize their basic form and function, even if it’s only at a superficial level.

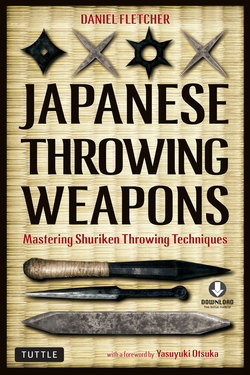

This is a selection of different types of shuriken.

Shuriken-jutsu means “hand release blade techniques.” It entails using shuriken in combat, primarily by throwing, but also by cutting or thrusting. For a long time, the practice of throwing shuriken has been most commonly associated with the ninja, but they were not the only users of these weapons. In fact, every Japanese school of martial arts has had, at some point in its history, at least one form of shuriken-jutsu in their teachings.

As a matter of fact, these weapons are not entirely unknown in the west. During the First World War, similar weapons were used as “bomblets” dropped by the hundreds from aircraft over enemy troops.

In World War I the Germans used these air darts.

It is thought that some of the earliest Japanese practices of shuriken-jutsu were examples of warriors throwing their short swords in battle. The samurai carried two or three swords: a long sword, a short sword and a dagger. The odds of striking a fatal blow against an armored opponent by throwing a short sword are very low. It was an unlikely maneuver, but not totally without merit, as practice in throwing the short sword became common. In some cases, even the long sword was thrown.

How a sword might be used as a throwing weapon.

The shuriken was never a weapon of great strategic importance to an army on the battlefield. During the Warring States period (1450 to 1600 AD), as in many other countries, battles were fought by large, strategically directed formations of men using weapons of distance.

When thousands of men joined in combat, weapons of range made the strategic difference. Long-distance weapons (cannon, firearms and the bow) were the great killers in feudal Japan (along with deliberately set fires). Formations fired on enemy formations; so combat was not typically man-to-man. Cannons would start the battle and then muskets and bows were employed. The ability to kill at a distance is the secret to survival in war. Cavalry and long spear formations would move around and basically finish the battle. Some of those spears were as long as 18 feet. Even though the spear was a hand-held weapon, it still provided the advantage of killing at a distance.

For those who were lucky enough to carry them, the firearm was the un-disputed supreme weapon. It had the range and power to kill that far exceeded the bow. The bow, however, was the main weapon before the arrival of firearms and continued to be used in great numbers even after the match-lock rifle appeared in battle. Once the sides closed and the advantage of the gun or bow was lost, armies fought with long spears. However, if a soldier lost his spear, he was in trouble, now he no longer had the ability to strike from a distance.

There are many pole arms that provide some distance, but in facing a line of thousands of long spears, only another long spear will be of use. There is a point, however, where an enemy gets too close for even a spear to be useful. There are a number of situations where an enemy can reach you before you can reload your musket or nock another arrow. This distance is the traditional domain of the sword, but it is also the domain of the shuriken.

One could say the shuriken was of great importance to an individual soldier on the battlefield, especially if he were to find himself on the losing side. Once the battle was clearly decided, the losers had three choices: be killed, be captured or escape. At this point, the possibility for close-quarters single combat was a distinct possibility. As the distance between combatants closed and their options ran out, the losing side had no choice but to resort to individual, last-ditch techniques. Such circumstances give rise to an artistic level of survival-inspired creativity. A soldier could find many possible weapons in the litter of a fresh battlefield—weapons lying on the ground or protruding from bodies like broken spears, broken swords, discarded knives, thousands of broken arrows, and pieces of broken armor plate. This may be why Tatsumi Ryu shuriken bear a very strong resemblance to a traditional Japanese yari (spear head).

Tatsumi Ryu Shuriken

Any of these battlefield remnants could be used as a buki (weapon) or as me-tsubushi (blinder/distraction). As a soldier on the losing side, all you had to do to survive was get off the field of battle and run. Even if you did not manage to kill your attackers, a distraction, a chance to escape would be enough. The chances of survival are much greater for the man who decides to distract his enemy and escape than for the man who decides to engage in combat.

After the age of wars there came a time of peace known as the Edo period (1600 to 1868 AD). The Edo period is called a peaceful period because there were no more great battles and widespread warring, but that does not mean that individuals were no longer fighting and killing other individuals with regularity. Many of the existing schools of martial arts were founded during the early Edo period. Often these schools “tested” each other by dueling, sometimes to the death, for the honor of their school. The early Edo period also saw thousands and thousands of suddenly unemployed soldiers roaming the countryside who had no other means of making a living. No longer were the fighting men confined to battlefields. During this time of “peace,” the potential for violence to individuals was possibly higher than during the age of wars. Crime was everywhere and there were few police officers. During the early Edo period, the Japanese people started to rebuild their country and grew wealthy, but violence and the fear of violence never left them. The practice of carrying (and using) concealed weapons became commonplace with men and women. There is a story from this period of the famous swordsman Musashi throwing his sword at an opponent. Musashi was losing a duel and was facing death. Were it not for shuriken-jutsu, the man reputed to be “the world’s greatest swordsman” would have been killed by a master of the kusarigama (chain and sickle). He was not the first or last warrior to do this.

Even today, training in shuriken-jutsu is tied closely to the use of the sword. Shuriken are usually thrown before or during the drawing of the sword or they are thrown during a sword fight as a surprise attack. There are even some shuriken designed to be held between the hand and the sword itself, making it easy to use both at the same time. Some martial arts schools consider the kozuka (by-knife) that is carried in the saya (scabbard) of the katana to be their only type of shuriken.

The kozuka was a small knife attached to the scabbard of the sword.

During the Warring States period and Edo periods, an incredible amount of creativity occurred with regard to weapons design and methods of concealing them. Every conceivable form of hand-held weapon found use in Japan at this time. Smaller, more concealable weapons, like the shuriken, were exploited and employed to a great extent. New schools were created and new shuriken designs and methods of hiding them on the body were developed.

Meifu Shinkage Ryu

The Meifu Shinkage Ryu is primarily a bo shuriken school. As such, we will only be discussing in depth the bo shuriken throw. There are two throwing techniques: the basic throw and the advanced throw. The basic throw will enable you to throw the shuriken and stick it in the target reliably and accurately. Compared to the advanced throw it is relatively slow and obvious, but without mastering the basic throw the advanced throw is impossible to learn. The advanced throw also contains a few secrets that Otsuka Sensei wishes to reserve only for his actual students and will not be discussed in this book. (Although there are some hints!) This is the way of many schools and is meant to encourage you to go to Japan and learn in person. Martial arts are not sterile, impersonal sets of factual information. They are living things that are passed down from teacher to student and they remain so to this day.

The Meifu Shinkage Ryu is a small school of martial arts in Tokyo, Japan. They are relatively unknown in the martial arts world and have fewer than forty students. There are no dojos or teachers outside of Japan and there is only one dojo in Tokyo. That “dojo” exists only in rented spaces for a few hours a week. The school is growing, however. Recently a small dojo was opened in Osaka and there are now two keikokai (informal training groups) outside of Japan. The reason behind its growth is the amazing skill of the present headmaster, Yasuykui Otsuka. His ability to throw shuriken with uncanny speed, accuracy and distance is far beyond that of any other masters of the art.

The Meifu Shinkage Ryu school was founded by the late Chikatoshi Someya. (1923–1999) When he was younger, Someya Sensei was a student of the Sugino branch of the Katori Shinto Ryu, a famous sword school. He was always very interested in shuriken-jutsu. In his later years, he decided to form his own school that focused solely on the shuriken. He maintained a good relationship with his former colleagues and to this day the Sugino Katori Shinto Ryu has a strong tie to the Meifu Shinkage Ryu. He devoted himself to refining and perfecting the art of shuriken-jutsu and some other concealed weapons.

Someya Sensei

At one time, there were several teachers of the Meifu Shinkage Ryu, but old age and illness have dwindled their number down to one. Otsuka Sensei believes that this number is going to rise very rapidly in the near future,

The Meifu Shinkage Ryu training focuses primarily on throwing the shuriken, but they also teach some hand-to-hand shuriken techniques, sword, chain and some unusual concealed weapons, such as the sho-ken (a small stabbing weapon).

Examples of the sho-ken (above left) and bo shuriken (below right).

Someya Sensei developed a fast and powerful throw, a technique that is limited in body movement, making it hard to see. To complement this new technique, he modified the design of his shuriken. He experimented with shuriken from different schools, and he also made and tested many new designs, searching for the perfect size and shape for his refined technique. He decided on the design the Meifu Shinkage Ryu uses today.

Shuriken prototypes developed by the Meifu Shinkage Ryu.

The original Katori Shinto Ryu blades owned by Someya Sensei resemble a type of bo shuriken called uchibari (house needles). These shuriken are common to many budo schools in Japan, including the Kukishinden Ryu and the Togakure Ryu. Not all shuriken called uchibari are identical. The “square torpedo” shape can be seen in several examples, often varying greatly in size.

These are examples of antique uchibari.

Otsuka Sensei likes to refer to the school as a “research group.” He uses this term because the study of the school is not wholly limited to the use of Meifu Shinkage Ryu weapons. He enjoys practicing with shuriken from many different schools (most of which are now extinct.) Almost all of the students in the Meifu Shinkage Ryu are students of other martial arts schools. Training is somewhat informal and open-minded when compared to other traditional Japanese schools of the martial arts.

Just as a modern police officer may carry a shotgun in his car, a service pistol on his belt, a backup pistol on his ankle, a baton, pepper spray, a taser and a knife, so too did ancient warriors carry an assortment of weapons, some were concealed and some were not. Samurai were allowed to carry any size and number of weapons they wanted, but they also carried shuriken secreted on their persons. A person of lesser status or a spy (ninja) would probably not wear any weapons openly but might have more than a dozen shuriken hidden in his clothing.

The people who lived through those dangerous times left behind an amazing diversity of weapons in form and function that is reminiscent of the innumerable species of insects you might see in a museum. Nowhere is this more evident than shuriken. In general, there are three categories of shuriken:

• Bo shuriken: “stick-like blades”

• Shaken shuriken: “wheel blades” Also called Hira shuriken “flat blade” or Senban shuriken “lathe blade.”

• Teppan shuriken: “iron plate blade”

In this book we will be looking at all three major categories of shuriken. We will discuss the different types, how they are thrown and how they were used as hand-held weapons. It is a gross overstatement and a mistake to suggest that one group of military men used any one type of shuriken exclusively, however, for the sake of clarity and maximizing the educational benefit of this book, we are going to divide the shuriken between two main schools (despite the fact that both schools use shuriken from both groups). There will be overlap, but that is a good thing. Our two schools will be the Meifu Shinkage Ryu and the Bujinkan (which is actually nine old budo schools taught together). We will look at the bo shuriken-jutsu of the Meifu Shinkage Ryu and the senban and teppan use of the Bujinkan.

Bo shuriken, as the name suggests, are stick-like (straight). They take many forms and sizes and most of them are between long 4 to 7 inches (12 and 18 cm) and weigh 1 ounce to 6 ounces (30 to 180 grams). In cross-section, they may be round, triangular, square, hexagonal or octagonal. They may be of constant thickness or they may taper sharply. Their shape usually depends upon their origin. Some shuriken designs evolved from common objects. Bo shuriken are often descended from nails, nail-drivers (kugi-oshi), metal chopsticks used to tend coals, broken arrowheads, broken spear heads, broken sword tips, unmounted knife blades, hair ornaments, by-knives, large needles, etc. Sometimes, however, they are original designs intended only for combat. The bo shuriken is by far the most commonly used type of shuriken in Japanese martial arts, perhaps because of the universal shape of its design. There are two major categories of bo shuriken: rod-like and dart-like. Rods are plain pieces of straight metal (non-aerodynamic). Darts are aerodynamic and have tails incorporated into their designs. The distinction is entirely subjective, but will help in understanding why the throwing methods differ between these two types.