Читать книгу The life of Friedrich Nietzsche - Daniel Halevy - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER III FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE AND RICHARD WAGNER—TRIEBSCHEN

ОглавлениеNietzsche installed himself at Basle, selected his domicile, and exchanged visits with his colleagues. But Richard Wagner was constantly in his thoughts. Three weeks after his arrival some friends joined with him in an expedition to the shores of the lake of the Four Cantons. One morning he left them and set off on foot by the river bank towards the master's retreat, Triebschen. Triebschen is the name of a little cape which protrudes into the lake; a solitary villa and a solitary garden, whose high poplars are seen from afar, occupy its expanse.

He stopped before the closed gate and rang. Trees hid the house. He looked around, as he waited, and listened: his attentive ear caught the resonance of a harmony which was soon muffled up in the noise of footsteps. A servant opened the door and Nietzsche sent in his card; then he was left to hear once more the same harmony, dolorous, obstinate, many times repeated. The invisible master ceased for a moment, but almost at once was busy again with his experiments, raising the strain, modulating it, until, by modulating once more, he had brought back the initial harmony. The servant returned. Herr Wagner wished to know if the visitor was the same Herr Nietzsche whom he had met one evening at Leipsic. "Yes," said the young man. "Then would Herr Nietzsche be good enough to come back at luncheon time?" But Nietzsche's friends were awaiting him, and he had to excuse himself. The servant disappeared again, to return with another message. "Would Herr Nietzsche spend the Monday of Pentecost at Triebschen?" This invitation he was able to accept and did accept.

Nietzsche came to know Wagner at one of the finest moments of the latter's life. The great man was alone, far from the public, from journalists, and from crowds. He had just carried off and married the divorced wife of Hans von Bülow, the daughter of Liszt and of Madame d'Agoult, an admirable being who was endowed with the gifts of two races. The adventure had scandalised all the Pharisees of old-fashioned Germany. Richard Wagner was completing his work in retreat: a gigantic work, a succession of four dramas, every one of which was immense: a work which was not conceived for the pleasure of men, but for the trouble and salvation of their souls; a work so prodigious that no public was worthy to hear it, no company of singers worthy to sing it, no stage, in short, vast enough or noble enough to make its representation possible. What matter! The world must stoop to Richard Wagner; it was not for him to yield to it. He had finished Rhinegold, and the Valkyries; Siegfried was soon to be completed; and he began to know the joy of the workman who has mastered his work, and is able at last to view it as a whole.

Restlessness and anger were mixed with his joy, for he was not of those who are content with the approbation of an élite. He had been moved by all the dreams of men, and he wished in his turn to move all men. He needed the crowd, wanted to be listened to by it, and never ceased to call to the Germans, always heavy and slow-footed in following him. "Aid me," he cries out in his books, "for you begin to be strong. Because of your strength do not disdain, do not neglect those who have been your spiritual masters, Luther, Kant, Schiller and Beethoven: I am the heir of these masters. Assist me. I need a stage where I may be free; give me it! I need a people who shall listen to me; be that people! Aid me, it is your duty. And, in return, I will glorify you."

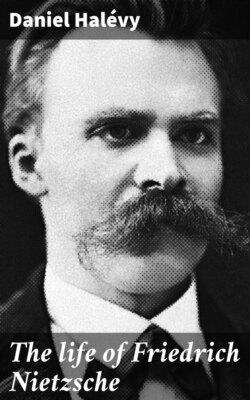

We may picture this first visit: Nietzsche with his soft manners, his nervous voice, his fiery and veiled look; his face which was so youthful in spite of the long, drooping moustache; Wagner in the strength of the fifty-nine years that he carried without sign of weakness, overflowing with intuitions and experiences, desires and expectations, exuberant in language and gesture. What was their first interview like? We have no record of it, but no doubt Wagner repeated what he was writing in his books, and said imperiously: "Young man, you too must help me."

The night was fine and conversation spirited. When it was time for Nietzsche to go, Wagner desired to accompany his guest on his way home along the river. They went out together. Nietzsche's joy was great. The want from which he had long suffered was now being supplied; he had needed to love, to admire, to listen. At last he had met a man worthy to be his master; at last he had met him for whom no admiration, no love could be too strong. He gave himself up entirely and resolved to serve this solitary and inspired being, to fight for him against the inert multitude, against the Germany of the Universities, of the Churches, of the Parliaments, and of the Courts. What was Wagner's impression? No doubt he too was happy. From the very beginning he had recognised the extraordinary gifts of his young visitor. He could converse with him; and to converse means to give and to receive. And so few men had been able to afford him that joy.

On the 22nd of May, eight days after this first visit, a few very intimate friends came from Germany to Triebschen to celebrate the first day of their master's sixtieth year. Nietzsche was invited, but had to decline, for he was preparing his opening lecture and did not like to be distracted at his task. He was anxious to express straightway the conception that he had formed of his science and of its teaching. For his subject he took the Homeric problem, that problem which is an occasion of division between scholars who analyse antiquity and artists who delight in it. His argument was that the scholars must resolve this conflict by accepting the judgment of the artists. Their criticism, fecund in useful historical results, had restored the legend and the vast frame of the two poems. But it had decided nothing, and could have decided nothing. After all, the Iliad and the Odyssey were there before the world in clear shapes, and if Goethe chose to say: "The two poems are the work of a single poet "—the scholar had no reply. His task was modest, but useful and deserving of esteem. Let us not forget, said Nietzsche at the conclusion of his inaugural lecture, how but a few years ago these marvellous Greek masterpieces lay buried beneath an enormous accumulation of prejudices. The minute labour of our students has saved them for us. Philology is neither a Muse nor a Grace; she has not created this enchanted world, it is not she who has composed this immortal music. But she is its virtuoso, and we have to thank her that these accents, long forgotten and almost indecipherable, resound again, and that is surely a high merit. "And as the Muses formerly descended among the heavy and wretched Bœotian peasants, this messenger comes to-day into a world filled with gloomy and baneful shapes, filled with profound and incurable sufferings, and consoles us by evoking the beautiful and luminous forms of the Gods, the outlines of a marvellous, an azure, a distant, a fortunate country. … "

Nietzsche was highly applauded by the bourgeois of Basle, who had come in great numbers to hear the young master whose genius had been announced. His success pleased him, but his thoughts went otherwhere, towards another marvellous, azure, and distant land—Triebschen. On the 4th of June he received a note:

"Come and sleep a couple of nights under our roof," wrote Wagner. "We want to know what you are made of. Little joy I have so far from my German compatriots. Come and save the abiding faith which I still cling to, in what I call, with Goethe and some others, German liberty."

Nietzsche was able to spare these two days and henceforward was a familiar of the master's. He wrote to his friends:

"Wagner realises all our desires: a rich, great, and magnificent spirit; an energetic character, an enchanting man, worthy of all love, ardent for all knowledge. … But I must stop; I am chanting a pæan. …

"I beg you," he says further, "not to believe a word of what is written about Wagner by the journalists and the musicographers. No one in the world knows him, no one can judge him, since the whole world builds on foundations which are not his, and is lost in his atmosphere. Wagner is dominated by an idealism so absolute, a humanity so moving and so profound, that I feel in his presence as if I were in contact with divinity. … "

Richard Wagner had written, at the request of Louis II., King of Bavaria, a short treatise on social metaphysics. This singular work, which had been conceived to fascinate a young and romantic prince, was carefully withheld from publicity, and lent only to intimates. Wagner gave it to Nietzsche, and few things surely that the latter ever read went home more deeply. As traces of the impression he received from it are to be discovered in his work down to the very end, it will be worth our while to give some idea of its nature.

Wagner starts by explaining an old error of his: in 1848 he had been a Socialist. Not that he had ever welcomed the ideal of a levelling of men; his mind, avid of beauty and order, in other words, of superiorities, could not have welcomed a notion of the kind. But he hoped that a humanity liberated from the baser servitudes would rise with less effort to an understanding of art. In this he was mistaken, as he now understood.

"My friends, despite their fine courage," he wrote, "were vanquished; the emptiness of their effort proved to me that they were the victims of a basic error and that they had asked from the world what the world could not give them."

His view cleared and he recognised that the masses are powerless, their agitations vain, their co-operation illusory. He had believed them capable of introducing into history a progress of culture. Now he saw that they could not collaborate towards the mere maintenance of a culture already acquired. They experience only such needs as are gross, elementary, and short-lived. For them all noble ends are unattainable. And the problem which reality obliges us to solve is this: how are we to contrive things so that the masses shall serve a culture which must always be beyond their comprehension, and serve it with zeal and love, even to the sacrifice of life? All politics are comprised within this question, which appears insoluble, and yet is not. Consider Nature: no one understands her ends; and yet all beings serve her. How does Nature obtain their adhesion to life? She deceives her creatures. She puts them in hope of an immutable and ever-delayed happiness. She gives them those instincts which constrain the humblest of animals to lengthy sacrifices and voluntary pains. She envelops in illusion all living beings, and thus persuades them to struggle and to suffer with unalterable constancy.

Society, wrote Wagner, ought to be upheld by similar artifices. It is illusions that assure its duration, and the task of those who rule men is to maintain and to propagate these conserving illusions. Patriotism is the most essential. Every child of the people should be brought up in love of the King, the living symbol of the fatherland, and this love must become an instinct, strong enough to render the most sublime abnegation an easy thing.

The patriotic illusion assures the permanence of the State but does not suffice to guarantee a high culture. It divides humanity, it favours cruelty, hatred, and narrowness of thought. The King, whose glance dominates the State, measures its limits, and is aware of purposes which extend beyond it. Here a second illusion is necessary, the religious illusion whose dogmas symbolise a profound unity and a universal love. The King must sustain it among his subjects.

The ordinary man, if he be penetrated with this double illusion, can live a happy and a worthy life: his way is made clear, he is saved. But the life of the prince and his counsellors is a graver and a more dangerous thing. They propagate the illusions, therefore they judge them. Life appears to them unveiled, and they know how tragic a thing it is. "The great man, the exceptional man," writes Wagner, "finds himself practically every day in the same condition in which the ordinary man despairs of life, and has recourse to suicide." The prince and the aristocracy which surrounds him, his nobles, are forearmed by their valour against so cowardly a temptation. Nevertheless, they experience a bitter need to "turn their back on the world." They desire for themselves a restful illusion, of which they may be at the same time the authors and the accessories. Here art intervenes to save them, not to exalt the naïve enthusiasm of the people, but to alleviate the unhappy life of the nobles and to sustain their valour. "Art," writes Richard Wagner, addressing Louis II., "I present to my very dear friend as the promised and benignant land. If Art cannot lift us in a real and complete manner above life, at least it lifts us in life itself to the very highest of regions. It gives life the appearance of a game, it withdraws us from the common lot, it ravishes and consoles us."

"Only yesterday"—wrote Nietzsche to Gersdorff on the 4th of August, 1869—"I was reading a manuscript which Wagner confided to me, Of the State and Religion, a treatise full of grandeur, composed in order to explain to 'his young friend,' the little King of Bavaria, his particular way of understanding the State and Religion. Never did any one speak to his King in a tone more worthy, more philosophical; I felt myself moved and uplifted by that ideality which the spirit of Schopenhauer seems constantly to inspire. Better than any other mortal, the King should understand the tragic essence of life."

In September, Friedrich Nietzsche, after a short stay in Germany, returned to a life divided between Basle and Triebschen. At Basle he had his work, his pupils, who listened to him with attention, the society of amiable colleagues. His wit, his musical talent, his friendship with Richard Wagner, his elegant manners and appearance, procured him a certain prestige. The best houses liked his company, and he did not refuse their invitations. But all the pleasures of society are less acceptable than the simplest friendship, and Nietzsche had not a single friend in this honest bourgeois city; at Triebschen alone was he satisfied.

"Now," he writes to Erwin Rohde, who was living at Rome, "I, too, have my Italy, but I am able to visit it only on Saturdays and Sundays. My Italy is called Triebschen, and I already feel as if it were my home. Recently I have been there four times running, and into the bargain a letter travels the same road almost every week. My dear friend, what I see and hear and learn there I find it impossible to tell you. Schopenhauer and Goethe, Pindar and Æschylus are, believe me, still alive."

Each of his returns was an occasion of melancholy. A feeling of solitude depressed him. He confided in Erwin Rohde, speaking at the same time of the hopes he had in his work.

"Alas, dear friend," he said, "I have very few satisfactions, and solitary, always solitary, I must ruminate on them all within myself. Ah! I should not fear a good illness, if I could purchase at that price a night's conversation with you. Letters are so little use! … Men are constantly in need of midwives, and almost all go to be delivered in taverns, in colleges where little thoughts and little projects are as plentiful as litters of kittens. But when we are full of our thought no one is there to aid us, to assist us at the difficult accouchment: sombre and melancholy, we deposit in some dark hole our birth of thought, still heavy and shapeless. The sun of friendship does not shine upon them."

"I am becoming a virtuoso in the art of solitary walking," he says again; and he adds: "My friendship has something pathological about it." Nevertheless he is happy in the depths of his being; he says so himself one day, and warns his friend Rohde against his own letters:

"Correspondence has this that is vexatious about it: one would like to give the best of oneself, whereas, in fact, one gives what is most ephemeral, the accord and not the eternal melody. Each time that I sit down to write to you, the saying of Hölderlin (the favourite author of my schooldays) comes back to my mind: 'Denn liebend giebt der Sterbliche vom Besten!' And, as well as I remember, what have you found in my last letters? Negations, contrarieties, singularities, solitudes. Nevertheless, Zeus and the divine sky of autumn know it, a powerful current carries me towards positive ideas, each day I enjoy exuberant hours which delight me with full perceptions, with real conceptions—in such instants of exalting impressions, I never miss sending you a long letter full of thoughts and of vows; and I fling it athwart the blue sky, trusting, for its carriage towards you, to the electricity which is between our souls."

And we can get a glimpse of these positive ideas, these precious impressions, because we are in possession of all the notes and the blunders of the young man who was acquiring, at the price of constant effort, strength and mastery.

"My years of study," he wrote to Ritschl, "what have they been for me? A luxurious sauntering across the domains of philology and art; hence my gratitude is especially lively at this moment that I address you who have been till now the 'destiny' of my life; and hence I recognise how necessary and opportune was the offer which changed me from a wandering into a fixed star, and obliged me to taste anew the satisfaction of galling but regular work, of an unchanging but certain object. A man's labour is quite another thing, when the holy anangkei of his profession helps him; how peaceful is his slumber, and, awakening, how sure is his knowledge of what the day demands. There, there is no philistinism. I feel as if I were gathering a multitude of scattered pages in a book."

The Origin of Tragedy proves to be the book the guiding ideas of which Nietzsche was now elaborating. Greek thought remains the centre round which his thought forms, and he meditates, in audacious fashion, on its history. A true historian, he thinks, should grasp its ensemble in a rapid view. "All the great advances in Philology," he writes in his notes, "are the issue of a creative gaze." The eyes of a Goethe discovered a Greece clear and serene. Being still under the domination of his genius, we continue to perceive the image which he has put before us. But we should seek and discover for ourselves. Goethe fixed his gaze on the centuries of Alexandrine culture. Nietzsche neglects these. He prefers the rude and primitive centuries, whither his instinct, since his eighteenth year, had led him when he elected to study the distiches of the aristocrat, Theognis of Megara. There he inhales an energy, a strength of thought, of action, of endurance, of infliction; a vital poetry, vital dreams which rejoice his soul.

Finally, in this very ancient Greece, he finds again, or thinks that he finds again, the spirit of Wagner, his master. Wagner wishes to renew tragedy, and, by using the theatre, as it were, as a spiritual instrument, to reanimate the diminished sense of poetry in the human soul. The "tragic" Greeks had a similar ambition; they wished to raise their race and ennoble it again by the most striking evocation of myths. Their enterprise was a sublime one, but it failed, for the merchants of the Piræus, the democracy of the towns, the vulgar herd of the market-place and of the port, did not care for a lyrical art which stipulated a too lofty manner of thought, too great a nobleness in deed. The noble families were vanquished and tragedy ceased to exist. Richard Wagner encounters similar enemies—they are the democrats, insipid thinkers, and base prophets of well-being and peace.

"Our world is being judaised, our prattling plebs, given over to politics, is hostile to the idealistic and profound art of Wagner," writes Nietzsche to Gersdorff. "His chivalrous nature is contrary to them. Is Wagner's art, as, in other times, Æschylus's art, to suffer defeat?" Friedrich Nietzsche is always occupied with a like combat.

He unfolds these very new views to his master. "We must renew the idea of Hellenism," he says to him; "we live on commonplaces which are false. We speak of the 'Greek joy,' the 'Greek serenity'; this joy, this serenity, are tardy fruits and of poor savour, the graces of centuries of servitudes. The Socratic subtlety, the Platonic sweetness, already bear the mark of the decline. We must study the older centuries, the seventh, the sixth. Then we touch the naïve force, the original sap. Between the poems of Homer, which are the romance of her infancy, and the dramas of Æschylus, which are the act of her manhood, Greece, not without long effort, enters into the possession of her instincts and disciplines. It is the knowledge of these times which we should seek, because they resemble our own. Then the Greeks believed, as do the Europeans of to-day, in the fatality of natural forces; and they believed also that man must create for himself his virtues and his gods. They were animated by a tragic sentiment, a brave pessimism, which did not turn them away from life. Between them and us there is a complete parallel and correspondence; pessimism and courage, and the will to establish a new beauty. … "

Richard Wagner interested himself in the ideas of the young man, and associated him more and more intimately in his life. One day, Friedrich Nietzsche being present, he received from Germany the news that the Rhinegold and the Valkyries, badly executed far from his advice and direction, had had a double failure. He was sad and did not hide his disappointment; he was afflicted by this depreciation of the immense work which he had destined for a non-existent theatre and public, and which now crumbled before his eyes. His noble suffering moved Nietzsche.

Nietzsche took part in his master's work. Wagner was then composing the music of the Twilight of the Gods. Page after page the work grew, without haste or delay, as though from the regular overflowing of an invisible source. But no effort absorbed Wagner's thought, and, during these same days, he wrote an account of his life. Friedrich Nietzsche received the manuscript with directions to have it secretly printed, and to supervise the publication of an edition limited to twelve copies. He was asked to oblige with more intimate services. At Christmas, Wagner was preparing a Punch and Judy show for his children. He wanted to have pretty figurines, devils and angels. Madame Wagner begged Nietzsche to purchase them in Basle. "I forget that you are a professor, a doctor, and a philologist," she said graciously, "and remember only your five-and-twenty years." He examined the figurines of Basle, and, not finding them to his liking, wrote to Paris for the most frightful devils, the most beatific angels imaginable. Friedrich Nietzsche, admitted to the solemnity of the Punch and Judy show, spent the Christmas festival with Wagner, his wife and family, in the most charming of intimacies. Cosima Wagner made him a present; she gave him a French edition of Montaigne, with whom, it seems, he was not acquainted, and of whom he soon became so fond. She was imprudent that day. Montaigne is perilous reading for a disciple.

"This winter I have to give two lectures on the æsthetic of the Greek tragedies," wrote Nietzsche, about September, to his friend the Baron von Gersdorff; "and Wagner will come from Triebschen to hear them." Wagner did not go, but Nietzsche was listened to by a very large public.

He described an unknown Greece, vexed by the mysteries and intoxications of the god Dionysius, and through its trouble, through this very intoxication, initiated into poetry, into song, into tragic contemplation. It seems that he wished to define this eternal romanticism, always alike to him, whether in Greece of the sixth century B.C. or in Europe of the thirteenth century; the same, surely, which inspired Richard Wagner in his retreat at Triebschen. Nietzsche, however, abstained from mentioning this latter name.

"The Athenian coming to assist at the tragedy of the great Dionysos bore in his heart some spark of that elementary force from which tragedy was born. This is the irresistible outburst of springtime, that fury and delirium of mingled emotions which sweeps in springtime across the souls of all simple peoples and across the whole life of nature. It is an accepted thing that festivals of Easter and Carnival, travestied by the Church, were in their origin spring festivals. Every such fact can be traced to a most deep-rooted instinct: the old soil of Greece bore on its bosom enthusiastic multitudes, full of Dionysos; in the Middle Ages in the same way the dances of the Feast of Saint John and of Saint Vitus drew out great crowds who went singing, leaping and dancing from town to town, gathering recruits in each. It is, of course, open to the doctors to regard these phenomena as diseases of the crowd: we content ourselves with saying that the drama of antiquity was the flower of such a disease, and if that of our modern art does not fountain forth from that mysterious source, that is its misfortune."

In his second lecture Nietzsche studied the end of tragic art. It is a singular phenomenon; all the other arts of Greece slowly and gloriously declined. Tragedy had no decline. After Sophocles it disappeared, as though a catastrophe had destroyed it. Nietzsche recounts the catastrophe, and names the destroyer, Socrates.