Читать книгу Fateful Transitions - Daniel M. Kliman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

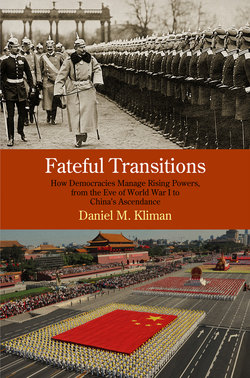

Fateful Transitions

An age-old question—how to manage the rise of new powers—looms large for the United States, Europe, and much of Asia. Although the nature of the emerging international order remains unclear, the geopolitics of the twenty-first century has earlier parallels. Since the late 1800s, the world’s major democracies have repeatedly navigated the ascendance of other nations. The choices made by democratic leaders during these fateful transitions have profoundly shaped the course of history. On the positive side, these decisions paved the way for the Anglo-American rapprochement; on the negative side, the path taken culminated in World War I, World War II, and the Cold War. This track record of limited success should give today’s leaders pause as they confront a world increasingly defined by fateful transitions.

As other powers rise, democratic nations have pursued a range of strategies. Sometimes they have appeased, sometimes they have integrated the rising state into international institutions, sometimes they have built up military capabilities and alliances, and sometimes they have contained the ascendant state. On occasion, they have even switched approaches midway through a new power’s emergence. This book explains the strategic choices that democratic leaders make as they navigate power shifts. It argues that an ascendant state’s form of government decisively frames transitions of power: democracies can rise and reassure while autocracies cannot. As a result, the strategies adopted by democratic leaders differ depending on the regime type of the rising power.

Domestic institutions shape external perceptions of a nation’s rise. On multiple levels, democratic government functions as a source of reassurance. Democracy clarifies intentions: decentralized decision-making and a free press guarantee that information about a state’s ambitions cannot remain secret for long. In addition, checks and balances coupled with internal transparency create opportunities for outsiders to shape a rising power’s trajectory. Other states can locate and freely engage with multiple domestic actors who all have a hand in the foreign policy of the ascendant state. Thus, democratic government mitigates the mistrust a new power’s rise would otherwise generate.

Autocracy has the opposite effect. By policing the media and confining foreign policy decisions to a select few, authoritarian government creates a veil of secrecy that obscures a rising power’s intentions. Moreover, in a centralized and opaque political system, opportunities to shape strategic behavior are slim. Enforced secrecy prevents external powers from identifying and subsequently exploiting rifts within the government. And outsiders have few domestic groups to engage because autocratic rule cannot tolerate independent centers of influence. Consequently, autocracy amplifies the concerns accompanying a powerful state’s emergence.

Regime type sets the boundaries for how democratic leaders formulate strategy. A democracy tends to accommodate when an ascendant state upholds rule of law and provides for domestic transparency. In an environment defined by relative trust and adequate information, a democracy can safely appease the ascendant state to remove points of conflict before integrating it into international institutions. By contrast, a democracy is likely to favor a different approach at the outset of an autocracy’s rise. Integration remains attractive as a tool for restraining and potentially reshaping an autocracy as it becomes more powerful. However, the existing climate of uncertainty and mistrust tends to compel a democracy to pair integration with hedging: developing military capabilities and alliances as a geopolitical insurance. This two-pronged approach is inherently fragile. If over time integration clearly fails to moderate a rising autocracy’s external behavior, a democracy will shift to containment.

The argument connecting power transitions, regime type, and strategy finds affirmation in a series of historical junctures beginning with the eclipse of Pax Britannica. At the turn of the twentieth century, Great Britain entered a period of relative decline as the United States and Germany burst onto the global scene. Although both of these emerging giants challenged Great Britain on diverse fronts, its strategies toward each sharply differed. Confident in American goodwill and perceiving significant opportunities to shape the United States into a pillar of the global order it had established, London appeased Washington, systematically eliminating all sources of tension with the rising power of the Western Hemisphere. Autocratic Germany, however, elicited a different British response. Wary of Berlin’s intentions and skeptical of London’s capacity to influence German foreign policy through internal lobbying, British leaders initially opted for integration and hedging. But when international institutions proved unable to limit German bellicosity, they transitioned to containment.

The British approach toward Germany’s resurgence under Nazi rule followed a similar course. German autocracy initially masked Adolf Hitler’s true intentions. Unsure whether they were dealing with the megalomaniacal Hitler of Mein Kampf or a reformed and responsible statesman, British leaders attempted to integrate Germany into a new European order while simultaneously ramping up military spending as a precaution. Once the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia demonstrated that no post-Versailles Treaty settlement could moderate German behavior, London pivoted to containment, declaring war when Hitler’s armies invaded Poland.

The onset of the Cold War similarly underscores how a rising nation’s domestic government frames power transitions. The Second World War catapulted the Soviet Union into a dominant position on the Eurasian landmass. Uncertainty rooted in the Soviet Union’s opaque political system compelled the United States to hedge against its ally while holding out hope that Moscow would join the new postwar order. However, Moscow’s temporary occupation of northern Iran, bullying of Turkey, and blockading of Berlin led Washington to conclude that integration had failed to restrain the Soviet Union. Accordingly, the United States moved toward a strategy of containing its erstwhile ally.

The ascendancy of China, which started in the mid-1990s and has accelerated since 2000, demonstrates that regime type continues to shape external perceptions of a nation’s rise. Censorship and state secrecy have cast a pall of uncertainty over China’s long-term ambitions, ensuring that the modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and recent episodes of assertiveness in the South and East China Seas provoke growing concern in Washington and Tokyo. Concentration of power at the apex of the Communist Party and the related absence of societal checks and balances deprive the United States and Japan of opportunities to shape China’s strategic behavior by engaging with a range of domestic actors. Thus, both democratic powers have moved to integrate China into the global order while simultaneously fielding new military capabilities and reinforcing strategic ties with each other and with additional countries in Asia. Despite changes of administration in both Washington and Tokyo, neither has deviated from this two-pronged approach.

Fateful transitions past and present point to multiple insights for contemporary policymakers.

First, the leadership in Beijing has wrongly bet that alleviating mistrust abroad will not require political reform at home. Integration into the global economy and rhetorical commitments to “peaceful development” and a “harmonious world” have failed to quell mounting concerns about China’s future course. These concerns are inextricably linked to China’s system of one-party rule, which magnifies anxieties that, in the best of circumstances, would attend the emergence of a new superpower. The absence of domestic political reform is now becoming a strategic liability as nations wary about China’s ascendance take steps that amount to quasi encirclement. Moreover, widespread mistrust threatens to ultimately constrict China’s ability to take a leadership role in the international community, depriving the country of the fruits of its rise.

Second, American leaders should recognize that integration, though essential, is no substitute for more actively promoting democratic reforms inside China. Encouraging gradual political liberalization is the only way to short-circuit the cycle of mistrust, reaction, and counter-reaction that increasingly defines relations between Washington and Beijing. Because China’s leadership would regard a U.S. push for overnight elections as a deeply hostile act, Washington should press for political reforms that do not inherently threaten the Chinese Communist Party. It can do so by giving consistent presidential attention to human rights and specific issues of democratic governance in China, supporting efforts that help Chinese officials strengthen their own institutions, and promoting a regional agenda that advances democratic norms in Asia.

Third, India’s ruling elites should recognize that influence comes not only from wealth and military power but also from the capacity to reassure. This is an advantage India enjoys thanks to its democratic institutions and one which is overlooked by many outside observers who see the parliamentary maneuvering and popular protests associated with representative government as a challenge to sustaining India’s economic takeoff. No penumbra of uncertainty surrounds India’s emergence on the world stage. In addition, outsiders can influence Indian foreign policy by engaging a diverse landscape of political parties, bureaucracies, business groups, media figures, and civil society actors. Consequently, despite India’s testing of nuclear weapons in the late 1990s and its accelerating military buildup, mistrust of its intentions remains low. The way is clear for India to rise into a position of global leadership.

Fourth, the United States should forge closer partnerships with rising democracies to strengthen the global order. For more than six decades, the rules-based international system has advanced peace, prosperity, and freedom. However, new challenges to the order have emerged. These include a weakened global financial architecture, expansive maritime claims in East Asia and beyond, the retrenchment of democracy in some parts of the world, and fiscal constraints in the United States and Europe. To adapt and renew the current system, Washington should look to rising democracies as the most promising partners. Unlike China or Russia, these new powers possess domestic institutions that permit the United States to work with them in an environment devoid of crippling mistrust and offer American leaders entry points into their foreign policy processes. U.S. engagement with rising democracies is critical. The choices these emerging powers make—about whether to take on new global responsibilities, passively benefit from the efforts of established powers, or complicate the solving of key challenges—may, together, decisively influence the trajectory of the current international order.

The world of the twenty-first century is a world of fateful transitions. In the years ahead, how to manage rising powers will increasingly preoccupy the foreign policies of the United States, Europe, and much of Asia. The flare-up of Japan-China tensions surrounding the Senkaku/Diaoyu island group and the revelation of widespread Chinese hacking against American government agencies and corporations have put a spotlight on whether current approaches toward the growth of Chinese power are working. Meanwhile, budgetary pressures on U.S. foreign affairs and defense spending will place an even greater premium on building partnerships with rising democracies. Within Europe, the continued weakness of many Eurozone economies after the debt crisis underscores the global power shift and focuses European capitals on how to navigate the rise of other states. Leaders in the world’s established powers—and their rising-state counterparts—would do well to keep in mind how regime type frames power transitions if they wish to avoid the mistakes of their predecessors.

The Book and International Relations Theory

This book speaks to multiple strands of international relations scholarship. It reinforces the extensive literature on the democratic peace and contains new insights for academic work on relations between declining and rising states. At the same time, the book examines whether arguments about the interplay of economic interdependence and foreign policy explain the strategic choices made by democratic leaders as they navigate power transitions.

The Democratic Peace

Scholars have devoted much attention to understanding why democracies, though about as conflict prone as autocracies, have “virtually never fought one another in a full-scale international war.”1 Potential explanations generally fall into one of two categories. Normative accounts of the democratic peace argue that democratic leaders externalize rules and practices that govern the domestic political arena, for example, nonviolent conflict resolution and “live and let live” attitudes toward negotiation. At the international level, these norms translate into mutual trust and respect among democracies, which prevent conflicts from escalating into war. However, democracies do not accord autocratic regimes the same trust and respect because the latter’s type of political system lacks norms that would moderate external conduct. Thus, disputes between democracies and autocracies may result in war.2

The other explanation for the democratic peace emphasizes the role of domestic institutions. In democracies, leaders are accountable to legislatures, major interest groups, and the general public. According to proponents of the democratic peace, this imposes a number of constraints on foreign policy. Publics will normally be averse to bearing the costs of war.3 Democratic institutions also give a voice to interest groups who may oppose military conflict for political or moral reasons. Mobilizing for war therefore constitutes a complex, drawn-out process as leaders try to convince the public and major societal actors to support military action. Consequently, democracies mobilize slowly and in the public eye. In crises featuring two democracies, neither need fear surprise attack—each recognizes that the other operates under similar domestic constraints. This provides ample time to peacefully resolve crises through locating mutually acceptable agreements.4

A different institutional argument for the democratic peace draws attention to the linkage between successful prosecution of war and political survival of elected elites. Democratic leaders should be more willing than their autocratic counterparts to devote resources to war because military defeat would erode the broad political base they require to remain in office. Recognizing that elected elites in other states confront the same incentives to expend significant resources in the pursuit of victory, democratic leaders will avoid costly conflicts with each other.5

The democratic peace is not without critics. Using regression analysis, Joanne Gowa observes no statistical evidence of a democratic peace prior to World War I or during the interwar period. Although the democratic peace appears statistically significant throughout the Cold War, Gowa attributes this finding to shared national interests: the Soviet threat compelled democracies to settle their differences peacefully.6 David Spiro points to the Spanish-American War and Finland’s membership in the Axis during World War II as examples of military conflicts among democracies.7 Critiquing the democratic peace from a different angle, Christopher Layne examines “near misses” where rival democratic states nearly went to war. According to Layne, in these cases factors other than externalized norms averted military conflict.8 Sebastian Rosato, in a critique of mechanisms underlying the democratic peace, contends that nationalist publics may demand war and that leaders can manipulate public opinion when initial support is lacking.9 Last, Edward Mansfield and Jack Snyder put forward a major qualification to the democratic peace. Using both statistical analysis and a series of case studies, they argue that well-developed political institutions and rule of law prove conducive to peace, but elected regimes at the early phase of democratic transitions are actually war prone.10

Proponents of the democratic peace have answered each of these critiques. Bruce Russett and John Oneal demonstrate that the democratic peace extends throughout the twentieth century. In their statistical analysis, “When the democracy score of the less democratic state in a dyad is higher by a standard deviation, the likelihood of conflict is more than one-third below the baseline rate among all dyads in the system.”11 Other scholars have replicated Russett and Oneal’s findings, and the significance of the democratic peace across time has largely ceased to generate debate.

The historical anomalies that Spiro and Layne identify have led to a more precise understanding of how the democratic peace operates. John Owen incorporates perceptions of regime type into democratic peace theory. He argues that pacific relations between democracies endure only when each state perceives the other as liberal. The Spanish-American War thus upholds the democratic peace because the United States perceived its European adversary as a monarchy. Owen also evaluates “near misses” in which democracies came close to conflict and finds that normative mechanisms actually operated to forestall war.12 Charles Lipson proposes that democracies have a special “contracting advantage.” Transparency, stable leadership succession, public accountability, and constitutional checks and balances enhance outsiders’ confidence that a democracy will abide by its commitments. Repeated interaction gradually increases confidence in another democracy’s reliability as a contracting partner. Lipson thereby accounts for why “near misses” may occur between democracies, particularly at the early stage of their relationship.13

Rosato’s challenge to the democratic peace has not withstood close scrutiny. David Kinsella notes that Rosato mischaracterizes the democratic peace. The theory extends to interactions between democratic states, yet Rosato treats it as an argument for democratic avoidance of war in all circumstances. In addition, Rosato tries to falsify the democratic peace by pointing to historical anomalies that existing scholarship has already addressed.14 Branislav Slantchev, Anna Alexandrova, and Erik Gartzke call attention to methodological flaws in Rosato’s analysis. Rosato casts the democratic peace as an inviolable law of international relations, yet it is a theory that predicts broad tendencies, not the foreign policy choices made by any given democracy. Slantchev and his coauthors also uncover selection bias in Rosato’s choice of evidence to refute the democratic peace.15 Michael Doyle critiques Rosato from a perspective rooted in the writings of the philosopher Immanuel Kant. Doyle argues that peace among democracies reflects three interlocking factors—“Republican representation, an ideological commitment to fundamental human rights, and transnational interdependence”16—and that by treating each factor separately, Rosato fails to grasp the actual logic of the democratic peace.

Significant flaws have emerged in the analysis underlying Mansfield and Snyder’s qualification of democratic peace theory. John Oneal, Bruce Russett, and Michael Berbaum use their own statistical model to evaluate whether democratization increases the likelihood of conflict. Their findings contradict those of Mansfield and Snyder: “democratization reduces the risk of conflict and does so quickly.”17 Vipin Narang and Rebecca Nelson show that states with fragile institutions experiencing democratic transitions have almost never initiated war. They demonstrate that the relationship between incomplete democratization and military conflict in Mansfield and Snyder’s statistical model hinges entirely on a series of wars associated with the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire. Narang and Nelson also challenge Mansfield and Snyder’s selection of case studies. Most feature countries with stable regimes or governments trending toward autocracy, not democratizing states with weak domestic institutions.18

This book intersects with the evolving democratic peace scholarship in several ways. It emphasizes the primacy of institutions over shared norms in promoting peace among democracies. The argument is that the byproducts of a state’s regime type frame outside perceptions of its rise. Decentralized authority and transparency work together to clarify intentions and create opportunities for the shaping of strategic behavior. Domestic institutions thus enable democracies to rise and reassure. The book’s focus on institutions rather than common values helps to move the democratic peace away from normative arguments grounded in Anglo-American political culture. Outside Great Britain and the United States, democratic leaders may not attribute ideological significance to the domestic arrangements of other nations. Yet the structural consequences of regime type should influence how democracies across different traditions and historical legacies relate to ascendant states.

The other contribution the book makes to the democratic peace is to extend the theory to an arena traditionally dominated by realism, an approach to international relations that downplays the impact of domestic political arrangements and prioritizes factors such as military capabilities and geography. These two factors, according to proponents of realism, should exert maximal influence over a state’s foreign policy during power transitions. Thus, the book affirms the democratic peace under conditions that should be least conducive to the theory.19

Power Transitions

Scholarship on power transitions has its origins in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, a chronicle of the struggle between Sparta and an ascendant Athens. The starting premise of most work on power transitions is that the “relative strengths of the leading nations in world affairs never remain constant, principally because of the uneven rate of growth among different societies.”20 International relations theorist Robert Gilpin builds on this premise to conceive the arc of history as “successive rises of powerful states that have governed the system and have determined the patterns of international interactions and established the rules of the system.”21 In his account, war occurs when a declining but still dominant state confronts a rising power. Invariably, the rising power will seek to alter international rules, the global hierarchy of prestige, and the distribution of territory among states. The reason is that a disjuncture exists between the rising power’s newfound preeminence and an international system reflecting the preferences of the now declining state. This embattled nation will attempt to right the balance of power; failure to reverse the power transition results in war. If victorious, the newly dominant power, having displaced the leading state, will set about creating a new international system more favorable to its interests.22

Perhaps the most developed line of argument in the scholarship on power transitions is located in the work of A. F. K. Organski. In Organski’s view, differential rates of industrialization produce an international system where the distribution of benefits lags behind changes in the balance of power. The probability of war hinges on two variables: the magnitude of the gap between the dominant state and the rising power, and the rising power’s degree of satisfaction with the existing international order. When the dominant state retains an unbridgeable lead, the prospects for war are negligible. No matter how revisionist, a weak nation has little recourse but to accept the current international order. However, as the dominant state declines, the likelihood of war increases with the rising power’s level of dissatisfaction.23 No longer unassailable, the flagging leader begins to question its ability to defeat the rising power in future conflicts. On the flipside, the rising power becomes ever more confident that war with the dominant state will bring about an advantageous reordering of the international system.

Organksi and scholars building on his work remain divided over the sequencing of power transitions and war. Originally, Organksi argued that rising powers initiate war before overtaking the dominant state. But in a later book, Organski and Jacek Kugler contend that wars only occur after the power transition is complete.24 Kugler and Douglas Lemke assert that the probability of war peaks at the moment of parity between the declining and rising states, while Robert Powell finds that the likelihood of war rises throughout the course of power transitions.25

Disagreements over the timing of conflict point to several areas of weakness in the foundational scholarship on power transitions. The advent of nuclear weapons calls into question the merit of examining power transitions largely from the perspective of war. The costs of conflict become prohibitive when both the dominant state and the rising power possess nuclear weapons. A dissatisfied and powerful state may wish to overturn the existing international order, but in the nuclear age, radical redistribution of territory by force no longer presents a viable option.26 Another oversight in the early scholarship on power transitions is the disproportionate attention accorded to choices made by the rising state. Woosang Kim and James Morrow acknowledge this: “We do not ask the question of why dominant states do not crush nascent challengers far in advance of their rise to power. The literature, to our knowledge, has never addressed this question, so we do not.”27

Not all the early scholarship falls into one or both of these analytical traps. Stephen Rock examines how reconciliation occurs between major powers. Through several case studies, including the Anglo-American power transition, he finds that compatible geopolitical goals and a common culture and ideology promote reassurance.28 Yet his approach leaves unanswered how a state might gauge a rising power’s intentions. Randall Schweller focuses on why democracies experiencing relative decline refrain from preventive war. He suggests they will accommodate other democracies as they rise and form defensive alliances against ascendant autocracies. However, Schweller offers only a cursory explanation for these choices, observing that because of shared values and common external enemies, democracies inevitably regard relations with each other as positive sum.29 In a study on the origin of great power conflict, Dale Copeland asserts that dominant states perceiving a sharp decline in their relative standing may resort to preventive war if they confront a single rising power.30 The focus on the dominant state’s strategy is useful, but the nuclear age would appear to rule out preventive war as a tool for navigating power transitions.

In recent years, a new wave of scholarship has significantly enriched the power transitions literature. Schweller in the opening chapter of an edited volume on China’s ascendancy distills history and theory to describe potential responses to a new power’s rise. Although some of these strategies blur together in practice, the menu of policy options he articulates represents a major step forward.31 David Edelstein too focuses on how states navigate unfavorable power shifts. He asserts that a declining but still dominant state will pursue cooperation if the ambitions of a new power appear susceptible to external manipulation. In drawing attention to beliefs about a rising state’s intentions, Edelstein makes a significant contribution.32 Yet his perspective overlooks how such beliefs ultimately reflect a new power’s regime type. Paul MacDonald and Joseph Parent examine a particular approach to relative decline: retrenchment. Surveying eighteen historical junctures, they find that a majority of great powers retract their strategic commitments when their position within the hierarchy of nations falls.33 A question that lingers is the extent to which the authors’ expansive definition of retrenchment sheds light on the concrete choices that states make during power shifts.

The new wave of scholarship also offers a more sophisticated treatment of power transitions and war. John Ikenberry points out that the probability of conflict will vary depending on the type of international order a state established before its decline. If the order subordinates other countries, a rising power will have few avenues to secure its interests other than war. But in the case of a “liberal order” that features rules-based governance and well-developed international institutions, an ascendant state will possess avenues to increase its voice and influence and consequently experience fewer pressures to pursue forcible change.34 In a study on the origins of peace, Charles Kupchan argues that the path to reconciliation begins with a unilateral concession and that enduring friendship between nations requires “compatible social orders and cultural commonality.”35 Although his analysis extends beyond power transitions, it contains important insights for how declining and rising states might avoid conflict.

Robert Art, forecasting the future of U.S.-China relations, observes that insecurity does not invariably accompany transitions of power. He contends that war is most likely when declining and rising states present a real or perceived threat to each other, and that the insecurity of the declining state matters most.36 Asking whether China’s ascendance will result in war, Charles Glaser takes a related approach. In his perspective, the severity of the security dilemma—the cycle of action and reaction in which the pursuit of security by one state triggers a countervailing response from another—can vary during power transitions. When defense and deterrence are easy, and states perceive each other as motivated by a desire for security rather than dominance, changes in the balance of power can unfold with a reduced likelihood of conflict.37 William Wohlforth offers a more pessimistic view of power transitions and war. He asserts that a state’s status depends on its capabilities relative to others. Leveraging research in psychology and sociology, Wohlforth argues that a clear imbalance of power among states promotes acceptance of the status quo. Power transitions muddy once-clear hierarchies and create incentives for status competition, which may translate into conflict.38

This book builds on the considerable advancements made by the power transitions literature over the past decade. It explains strategy formulation rather than the outbreak of war, and examines the choices of the initially dominant state. The book’s focus on regime type also addresses a major oversight in the current scholarship: how national leaders form beliefs about a new power’s intentions and why these beliefs evolve over time.

Economic Interdependence

Statesmen and scholars have long expounded that economic interdependence causes peace. One formulation of this argument points to mutual selfinterest: nations become less inclined to fight wars as the costs of disrupting trade and investment flows increase.39 Other arguments linking commerce to peace focus on the second-order effects of economic interdependence. The exchange of goods and ideas across borders may reshape identities. As they become increasingly cosmopolitan, citizens of commercial states are less likely to view foreigners as inherently threatening.40 Trade may also give rise to domestic groups with a vested stake in peace. These groups can leverage their new wealth to lobby for a pacific foreign policy congruent with their commercial interests.41 Last, economic interdependence may promote peace by offering policymakers a way to credibly telegraph their intentions without resorting to force. A state’s willingness to reduce lucrative trade and investment flows constitutes a powerful signal that alleviates uncertainty about resolve. This in turn diminishes the likelihood of miscalculation during disputes.42

Statistical research has yielded considerable support for claims about the relationship between economic interdependence and peace. Since the mid-1990s a number of studies have found a significant correlation between high levels of trade between pairs of countries and a diminished propensity for conflict. Oneal and Russett use regression analysis to demonstrate that commercial interdependence is associated with more pacific bilateral relations before World War I, during the interwar period, throughout the Cold War, and after.43 In their book Triangulating Peace, Russett and Oneal again test whether the existence of important economic ties coincides with decreased conflict between states. They find that the probability of violent disputes declines by 43 percent when each country is economically dependent on the other.44

This “commercial peace” is not without critics. Katherine Barbieri uses regression analysis to show that higher economic interdependence enhances the risk of conflict between countries.45 Copeland argues that expectations about future trade determine whether commercial ties foster peace or foment war. His logic is that a deep trading relationship can only underpin peace if both states foresee its continuation; if they anticipate a breakdown in future trade, highly dependent states fearing that the resulting economic loss will diminish their relative power may come to regard war as an attractive option.46

Proponents of the commercial peace have refuted each of these critiques. A number of scholars have suggested that Barbieri’s measure of economic interdependence may account for the positive relationship between trade and conflict that she identifies. Oneal and Russett further question the scope of her regression analysis, which includes all potential pairs of countries. They demonstrate that Barbieri’s main finding is a statistical mirage: trade only increases the likelihood of violence between states that lack the proximity or power to fight each other.47 Oneal, Russett, and Berbaum test whether expectations of future commerce matter. Their analysis contradicts Copeland’s argument. Historical trends in bilateral trade levels—a key point of reference for national leaders trying to forecast the future—appear to have minimal impact on the frequency of conflict between states.48

Another critique questions whether the line of cause and effect runs from trade to peace or peace to trade. Early arguments of this kind focus on how political relationships between states may facilitate commerce. Gowa and Mansfield contend that allied states are more likely to trade with each other because the gains in national wealth will strengthen their collective capabilities. Surveying most of the twentieth century, they conclude that alliances have a significant and positive influence on bilateral trade flows.49 More recent arguments in this vein emphasize the simultaneous interaction between trade and conflict. In separate studies, Omar Keshk, Brian Pollins, and Rafael Reuveny, and Hyung Min Kim and David Rousseau reassess the commercial peace while accounting for reciprocal cause and effect. Both studies show that economic interdependence has no pacific benefit.50

This challenge to the commercial peace has not gone unanswered. In an early survey of the simultaneous interaction between trade and conflict, Soo Yeon Kim determines that the strongest line of cause and effect runs from commerce to peace.51 Oneal, Russett, and Berbaum likewise demonstrate that while a two-way relationship characterizes trade and conflict, a dispute between states will only depress bilateral commerce for a short period. Controlling for several factors that might influence trade flows, they also find that alliances have no impact on commerce between states.52 Last, Havard Hegre, Oneal, and Russett uncover methodological flaws in the two recent studies negating the commercial peace. They “show that the pacific benefit of interdependence is apparent when the influences of size and proximity on interstate conflict are explicitly considered.”53

A subset of the literature on trade and peace explores how economic interdependence interfaces with domestic politics to shape a state’s strategic choices. Paul Papayoanou maintains that extensive economic ties with a rival power will hinder a state’s capacity to hedge or contain. Groups that directly benefit from commerce with the rival power will be reluctant to view it as hostile and oppose the adoption of confrontational policies. In addition, political leaders will fear the consequences of a more assertive strategy—that the rival power will sever commercial relations, resulting in painful economic dislocation at home. Papayoanou argues that democracies are more vulnerable to both of these dynamics because they accord all interests a voice in the making of foreign policy.54 Kevin Narizny advances a related argument. Sectors dependent on an external power for their economic livelihood will champion a foreign policy of accommodation while sectors that compete with that power in third markets will prefer more hardline approaches. Sectors reliant on trade and investment with a multitude of foreign partners will advocate international law and institution building but stand ready to oppose aggressors that threaten regional or global stability. The balance of these sectors within a state’s ruling political coalition will dictate its strategic choices.55

The commercial peace scholarship thus offers another vantage point for understanding how democratic leaders formulate strategy during power transitions. Trade and investment linkages may impose comparatively greater constraints on the rising state if its economy remains smaller than the democratic power’s. Yet if trade with the rising state constitutes a sizeable percentage of the democratic power’s national wealth, or if other types of economic entanglements exist, the potential loss of valuable commercial relations and the prospect of domestic blowback may overhang democratic leaders as they decide whether to appease, integrate, hedge, or contain. Except for the onset of the Cold War, all the case studies in this book feature nonnegligible economic ties between the democratic power and the ascendant state. Although the limited number of power transitions in the book provides an insufficient basis for broader claims about the role of economic interdependence, the analysis of multiple cases allows for a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between commercial ties and foreign policy.

Ordering of the Book

The remainder of the book offers an analytical framework and supporting historical evidence that, in turn, illuminate the geopolitics of the twenty-first century. Chapter 2 explains how regime type frames power shifts and sets the stage for how democratic states respond to the emergence of other powers. The next five chapters cover a period of time stretching from the late nineteenth century to the present. Chapter 3 explores the British responses to the simultaneous rise of the United States and Imperial Germany. Chapter 4 looks at Great Britain’s approach to the resurgence of Germany during the 1930s. Chapter 5 focuses on how the United States in the 1940s managed the rise of the Soviet Union. Chapters 6 and 7 respectively examine how the United States and Japan have responded to the growth of Chinese power. Chapter 8 discusses the scholarly and policy implications of the book’s main findings.