Читать книгу The Bad Boy of Athens - Daniel Mendelsohn - Страница 6

Preface

ОглавлениеIn the autumn of 1990, when I was thirty years old and halfway through my doctoral thesis on Greek tragedy, I started submitting book and film reviews to various magazines and newspapers, had a few accepted, and within a year had decided to leave academia and try my hand at being a full-time writer.

On hearing of my plans, my father, a taciturn mathematician who, I knew, had abandoned his own PhD thesis many years earlier, urged me with uncommon heat to finish my degree. ‘Just in case the writing thing doesn’t work out!’ he grumbled. Mostly to placate him and my mother – I’d already stretched my parents’ patience, after all, to say nothing of their resources, by studying Greek as an undergraduate and then pursuing the graduate degree – I said yes. I finished the thesis (about the role of women in two obscure and rather lumpy plays by Euripides) in 1994, took my degree, and within a week of the graduation ceremony I’d moved to a one-room apartment in New York City and started freelancing full-time.

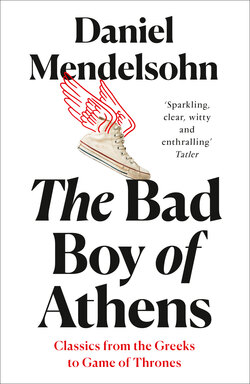

This bit of autobiography is meant to explain the contents and, to some extent, the title of the present collection of essays that I’ve published over the past two decades. When I was first settling into my new life, I was eager to leave my academic past behind and write about genres that I’d been passionate about since my teens (opera, film, theatre, music videos, and television) and subjects that exercised a particular fascination for me (not only the ancient past but family history; sexuality, too). This I began to do, as a perusal of the Table of Contents here will show. But fairly early on in my freelancing career, I found myself being asked by editors who knew I’d done a degree in Classics to review, say, a new translation of the Iliad, or a big-budget TV adaptation of the Odyssey, or a modern-dress production of Medea. I ended up finding real pleasure in these assignments, largely because they allowed me to write about the classics in a way that was, finally, congenial to me. My graduate-school years had coincided with a period in academic scholarship remembered today for its risibly dense jargon and rebarbative theoretical prose; writing for the mainstream press about the ancient cultures I’d studied allowed me to think and talk about the Greeks and Romans in a way that for me was more natural, more conversational – more as a teacher, that is, putting my training in the service of getting readers to love and appreciate the works and authors that I myself loved and appreciated. Euripides, for instance, to whom the title of this collection refers: formally experimental, darkly pessimistic in his view of both men and gods, whose existence he repeatedly questions, happy to poke fun at august predecessors such as Aeschylus, he really was the ‘bad boy’ of Athenian letters; in my essay on Fiona Shaw’s performance in his Medea, I saw no reason not to call him just that.

The desire to present the ancient Greeks and Romans and their culture afresh to interested readers – and, as often as not in these essays, to ponder what our interpretations and adaptations of them say about us – informs many of the pieces in this collection. A new translation of Sappho, for instance, provided an occasion to think about why that poet and her intense, eroticized subjectivity means so much to us today – although what she means to us may be quite different from what she meant to the Greeks; Oliver Stone’s blockbuster biopic Alexander, for its part, was a useful vehicle for thinking about why a mania for historical ‘accuracy’ doesn’t always make for good cinema. So, too, with my reconsiderations of Euripides’ vengeful Medea, whose modernity may reside elsewhere than many modern interpreters imagine; or of Virgil’s Aeneid, which may be unexpectedly contemporary in ways that have little to do with its much commented-on celebration of empire.

But most of the essays here are not about the classics per se, although they inevitably, and I hope interestingly, betray my attachment to the cultures I studied long ago. Hence a review of a pair of recent movies about artificial intelligence, Ex Machina and Her, begins – necessarily, as I see it – with a consideration of the robots that appear in Homer’s epics and what they imply about how we think about the relationship between automation and humanity. And an essay written for the centenary of the Titanic disaster sees, in its enduring fascination for popular culture, ghosts of the most ancient of myths: about hybris and nemesis, about greedy potentates and virgin sacrifice, about an irresistible beauty that the Greeks understood well – the beauty of the great brought low.

Still other pieces here reflect other, more figuratively ‘Greek’ interests of mine. There is a series of review-essays on plays and movies that feature powerful female leads (on Tennessee Williams, and on Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours, about Virginia Woolf, and the movie based on it). I see now that all of these are haunted by my long-ago dissertation on ‘brides of death’ in Euripides’ dramas, and the questions this motif raised about the ways in which male writers represent extremes of female suffering. Another series of essays focuses on works by or about gay authors: from Noël Coward, a great favourite of mine, to the most recent film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s greatest play, to Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love, a drama about A. E. Housman that pointedly contrasts that ‘dry as dust’ classicist-poet with Wilde.

Finally – and unsurprisingly, given that I am also a memoirist – there is a sequence of pieces that ponder the way in which writers’ personal lives intersect with their literary work. Susan Sontag’s diaries, Patrick Leigh Fermor’s elaborately self-mythologizing travel narratives, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s heavily autobiographical My Struggle novels, Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life: all of these betray fascinating and, sometimes, uncomfortable negotiations between literature and the lives we – and sometimes our readers – lead. The collection ends with one of my own entries into this field, one that combines many of the themes I have mentioned: the Greeks, powerful female figures, homosexuality, writing. In ‘The American Boy’, I recall my youthful epistolary relationship with the historical novelist Mary Renault, who did much to encourage both my love of Greek culture (which, in my adolescent mind, was complicatedly connected to my growing awareness of my homosexuality) and my desire to be a writer. The form of that essay, which entwines personal narrative with literary analysis, is one that I have employed in all three of my book-length memoirs, the most recent of which is An Odyssey: A Father, a Son and an Epic, about how reading Homer’s epic brought my late father and me together in unexpected ways, and which will be familiar to some of my British readers.

A personal consideration of another kind allows me to close this brief introduction. At the end of each of the pieces here, I have preserved the original datelines; all were written for periodicals, and such editing as has been done served merely to smooth out certain roughnesses or approximations that are inevitably the result of writing to a deadline. The datelines are meant as a reminder that every piece of criticism – every piece of writing, really – arises out of a certain moment in its author’s life, a certain way of thinking about a subject, a certain set of tastes or prejudices. That context, those prejudices, are important for readers to be reminded of not least because they can change and evolve over the years. The author overseeing the selection of essays for a collection such as this one, which contains a career’s worth of writing, is not necessarily the same person who wrote some of those essays. Such collections may be thought of as maps of an intellectual journey – one that, like Odysseus’s, takes years to complete. Each stop along the way is worth remembering, even though we’d experience it quite differently were we follow the same itinerary today.

This was brought home to me rather vividly only recently. One of the earliest pieces collected here is the long review I wrote about The Invention of Love; in it, I took strong exception to Tom Stoppard’s characterization of A. E. Housman – undoubtedly a rather spiky figure, but one for whose philological rigour and almost touchingly Victorian work ethic I nonetheless have a soft spot, for reasons I go into in the piece. When I first saw Stoppard’s play, in its pre-Broadway Philadelphia run, I disliked the way in which, at the climax of the drama, Housman is contrasted – unfairly, I thought – with the far more popular Oscar Wilde, a beloved figure whose self-martyrdom for what many (myself included) see as a foolish passion has endeared him to audiences in a way that the reserved Housman could never compete with. When my review came out, Stoppard published a strong rebuttal in the back pages of The New York Review of Books, and the heated exchange between us that ensued went several rounds before it finally petered out.

That was nearly twenty years ago, and I didn’t think much more of any of this until last year when, to my astonishment, I opened my mailbox to find a handwritten letter from Tom Stoppard. In it he had some very kind things to say about An Odyssey, which he’d just read. Gratified, a little bit mortified, and impressed by his generosity, I wrote back right away; after exchanging a few emails we agreed to meet during his next visit to New York. I like to think we both very much enjoyed that visit, not least because we simultaneously admitted to being equally bemused, now, by the heat that we’d brought to our ferocious exchange two decades earlier – when, as I can see now, I was enjoying rather too much, as one does at the beginning of one’s career, being a bit of a ‘bad boy’ myself. I hope he won’t mind that I’ve included that essay here; but this is where it belongs.