Читать книгу Foundational missionaries of south american adventism - Daniel Plenc - Страница 7

Оглавление3

Geörg (Jorge) Heinrich Riffel

By Sergio E. Becerra

Introduction

The origins of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Argentina are closely linked to the missionary efforts of two lay leaders from Entre Ríos province, Argentina: Geörg (Jorge) Riffel1 y Reinhardt (Reinaldo) Hetze. Both were German immigrants from the Volga2 who settled on the west of the Entre Ríos province together with other German families from the Volga in the second half of the 19th century, seeking economic, religious and social stability.

During the 19th century, one method favored by Adventist missionaries throughout the world was to arouse interest in Adventism among the Protestant communities and even among Sabbath-keepers,3 who due to their religious background would be more sensitive to the Adventist message. This was the preferred model to enter South America, since the first colporteurs for reasons of language and/or religious affinity, sought to sell their religious books and win interested people among the European migrant communities of Protestant background wherever possible.4 That was the case of the small community of Adventist believers among The Germans from the Volga, that was born and grew in its first years among German migrants of Protestant background. Unlike what happened other places, this foundational task was not in the hands of North American missionaries, but it was the result of the labor of Jorge Riffel and Reinaldo Hetze, lay leaders whose Adventist conviction led them to share their hope with neighbors and family years before the church would send an official missionary to Argentina.

Background and Preparation

The Riffels came originally from the valley of the Upper Rhône, today a part of the Canton of Valais, in Southwest Switzerland. The meaning of the Riffel name is “flax comb or rake,” that is in turn related to the verb riffeln, “to comb”.5 Undoubtedly, it refers to the family job in their original living place, that consisted of growing, combing and selling flax for cloth making.

Some of them embraced the Protestant faith during the Reformation. The valley of the Upper Rhône was part of Church lands, its prince was the Bishop of Zion, at that time. It was a time of upheaval and great religious intolerance. This forced the Riffels to leave their homes and principality behind to move to the north of Switzerland in search of a region with population of the same faith. Finally, they settled in the south of Germany, where they became farmers.6

The invitation of Kaherine the Great to settle in Russia was attractive, as well as other residents of the German Empire of the 18th century, after decades of suffering wars, hardship and violence. Germany was coming out of seven years of bloody international war. The decrees of this sovereign of German ancestry, according to which their professions and faith would be respected, they would be exempt from taxes and the duty of serving in the Russian army, plus the giving of land were very convincing. The Riffels moved to Russia and settle in a Protestant settlement called Deutsch Scherbakovka, founded in 1756 west of the Volga River (the Bergseite), south-west from Saratov. There Geörg (Jorge) Heinrich Riffel was born in January of 1850, in the home of Petter Riffel and Susana Kraft.7

Although at the beginning life’s conditions in the new land were not easy, a hundred years later the loss of certain privileges granted by the Russian crown, with the addition of the lack of land for the new generation,8 provoked a new migration. Encouraged by reports of the first emigrants to the United States and Brazil, in the settlements enthusiasm arose to leave in search of a better future in American land. Heart-rending were the farewell moments between the young emigrants and their elders that stayed behind. Because of scarcity means of communication and transportation, they realized they would not see them again.9 By that time, Jorge Riffel had married María Ziegler and they had a son named David who was three years old by that date. Along with other Germans from the Volga, Riffel decided to leave with his family to Brazil in November of 1876. They set off on a long journey across Russia and then to the port of Bremen to board a ship that would take them to the southern hemisphere. In Brazil, they settled in the state of Río Grande do Sul for three or four years. These were not fortunate because of bad crops. It was apparent that tropical lands were not suitable for growing wheat, staple of this community. Around 1880, Riffel decided to leave for Argentina, where a big number of Germans from the Volga had concentrated in the Diamante department of the Entre Ríos province.10 Again, conditions were unfavorable. Bad crops followed plagues of locusts between 1885-1886 that forced them to choose another emigration, this time to the USA. They settled near the family of Friedrich (Frederick) Riffel, brother of Jorge, in Tampa, Marion County, Kansas State. Thus, after a decade of separation, the Riffel brothers found themselves farming the land together in the United State.

It is then that an incident happens that changed radically the course of their lives. Around 1888, Louis R. Conradi, a young German evangelist from Michigan, carried out meetings in Hillsboro and Lehigh aimed at the community speaking that language. In reports written in the periodical of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Conradi, H. Schultz y S. S. Schrock praised God for the excellent response he and his associates had. Since 1884, work was done among the Germans of the Volga in Tampa with excellent results. In 1888 the combined membership of Hillsboro, Lehigh and Clark churches were about 500 people.11

The families of Jorge and Frederick Riffel attended the meetings of this Adventist preacher. As a result, both families were baptized in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Jorge Riffel embraced the Adventist faith with enthusiasm. He attended Adventist camp meetings and conferences and began a lively correspondence with friends in Argentina sharing with them his new faith. Over time, he received letters from Entre Ríos indicating that his efforts were bearing fruit. A friend, Reinhard Hetze, wrote to him saying he would keep the Sabbath if somebody would do so with him.12 Next year, Riffel decided to return to Argentina as self-supporting missionary, intending to share his new faith with family and acquaintances that were Germans of the Volga. Riffel encouraged his brother Frederick to go with him, but he did not since he had to support a family of ten children and thought he was in no place to start a new uprooting. However, Adán and Eva Zimmermann, Augusto and Cristina Yanke and Osvaldo and Eva Frick and their families joined Riffel.13

The travelers arrived at the port of Buenos Aires in February of 1890. The Riffels continued to the port of Diamante without waiting for the other three families delayed by immigration procedures. Hetze was waiting for them and took them home, 15 kilometers from the port. During the journey, Jorge taught and exhorted Hetze regarding his faith. Then, Hetze decided to accept the Adventist teachings, becoming the first South American Adventist convert, along with his family. It was a Friday, and everybody made plans to celebrate the first Sabbath together.14 At that time, the Hetzes lived near the confluence of Ensenada and Gómez creeks. It was in the property of Hetze that it was held the first meeting of Adventist believers in the Argentine Republic a Sabbath day of February of 1890.

The Riffels obtained lands in the district of Isletas, near Camps, Department of Diamante, Entre Ríos. Soon they were joined by a small core of Adventist families composed by the immigrant families and those of the new converts. Hetze moved to live among them, too. This gathering of believers was known in the place as the “Sabbatarian Colony.”15 There were 20 people that kept the Sabbath. First, they met in the house of Hetze and then in a small chapel by the cemetery of present-day Aldea Jacobi. He would live in this place until his death.

His Work and Method

Jorge Riffel experienced an intense desire of sharing his Adventist faith after his conversion. Reinaldo Hetze pointed out that Riffel wrote him from the USA telling him about his new beliefs and that they would come to share with him the truth about the Sabbath.16 The exchange with Hetze and the reading of an article by Ellen G. White encouraging believers speaking in other languages to volunteer as self-supporting missionaries encouraged them to return to Argentina.17 After arriving to Argentina, he did not stop actively preaching, teaching, baptizing and organizing the church.

Evidently, his method is witnessing through exhortation to relatives, friends and acquaintances, Bible study and testimony through his life example. The memories of his descendants talk about a missionary Jorge Riffel who was persuasive, insistent and convinced that Christ would return soon and whose duty was to warn everyone willing to hear him. And his vision went beyond his place and the community surrounding him. He combined farm work to support his family with mission work near and far from his home. One descendant states that Riffel used to periodically hitch up his horse to his Russian carriage, loading some hay bundles to feed the animal and serve as a makeshift bed, and thus leave for several days to visit German settlements in distant places of the Entre Ríos province.18

He complemented this task with supporting the work of the local church, as lay leader and preacher. Finally, when the church organization was established, he supported it with his own funds and got involved in affirming the work of evangelist pastors. The church repaid this calling by granting him missionary credentials and licenses and appointing him member of different administrative boards.

By 1891 arrived the first Adventist missionaries sent by the organization of the church. When the leadership of the church knew of the existence of this group of German-speaking believers and other immigrants, they saw the need of strengthening them and building a solid Adventist presence. It was decided to send colporteurs Edwin W. Snyder, Albert B. Stauffer and Clair A. Nowlin.19 Their task was to distribute Adventist publications as a means of evangelization. They worked with publications in English, French and German, but they communicated poorly in Spanish and had no literature to sell in that language. Stauffer, who was German, worked quite a lot among German settlers.

In 1892, the Foreign Missions Board of the General Conference sent L. C. Chadwick to Argentina to visit the colporteurs. He also met with Adventist German of the Volga families of Entre Ríos.20 He advised the leaders of the group, trained and preached to the converts that until then had not heard the exhortation of an Adventist pastor. In his own words, he states:

I think I never enjoyed so much freedom to preach the Word. The meetings were held in a mud house of one of the brethren and the attendance of the neighbors was good. There are eight families of Sabbath keepers in the settlement and since their houses are a stone’s throw away from each other’s, they are well placed for the meetings. The last Sunday we were there with them, two of the brethren were chosen as leaders of the group and a third as treasurer. A Sabbath School director was also chosen and since they had just received the first copies of a subscription for Hausfreund they will be able to obtain their Sabbath School lessons from it.21

The appointed leaders where, undoubtedly, Riffel and Hetze, that had naturally been established as leaders of the small Adventist community. Chadwick stated that he did not see that the group was ready to be organized as church because it needed more instruction than what he could offer them, but the members would wait patiently for a German-speaking worker to be sent to them, who would find many doors open among the settlers thanks to the work of Riffel and the first Adventist families of Germans of the Volga.

A year later arrived Frank H. Westphal, Adventist pastor coming from the Illinois Conference, USA, sent by the Foreign Missions Board to organize the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Argentina.22 After taking a week to settle his family in Buenos Aires, he traveled immediately to Entre Ríos to take care of the small community of German-speaking believers, the main motive of his trip.23 His arrival produced a great sensation. Quickly, a group of listeners gathered. The first night a sizable group met to hear him preach. After hearing the first sermon and attempting to close the meeting with a hymn and a prayer, he was surprised that nobody left. He preached a second and even a third sermon, after which they let him close with the promise of meeting again the next day.24 This incident clearly shows the interest aroused by the Adventist message and the desire for greater religious instruction. A congregation was soon organized, the first in the Southern Cone, with 36 members but it quickly increased to 200.25 Westphal was reaping the work began by Riffel. There are testimonies that affirm that he had taught and baptized, together with Hetze, several interested people that became the core of the first congregation, as well as that of Diamante.26

After the organization of the first Adventist congregations, the support of Riffel and Hetze to witnessing did not abate. The magazine of the church points out how Riffel contributed with evangelism in the cities of Entre Ríos by himself or along with pastor Godofredo Block, one of the first native pastors. They also participated actively in administrative meetings of the church, then in the organization of the South American Union. Riffel was member of the executive board several times. Both showed their commitment to the development of the church and its work, contributing with generous donations for the purchase of a press for the church in Chile. The organization of the church recognized the valuable contribution in time, dedication and material support granting them missionary licenses or credentials that authorized them to fulfill some ministerial responsibilities.

Qualities and Motivation

In the personality of Riffel stands out the conviction with which he embraced the Adventist faith and the spirit he used from then on to share his faith and to support the beginning of the Adventist organization. He showed it first in his correspondence with Hetze trying to convince him to his new faith. In expressing this interest on the Sabbath and Adventist doctrines but making his affiliation to Adventism dependent on the support of other believers, Riffel mobilized to form a group of missionaries that would be willing to move for good to Argentina, including his family, to be part of the group of believers that would begin the seeding of Adventism in Argentina.

With the development of a group of regular believers in Entre Ríos, he took the initiative of making contact with the General Conference insisting in the need of a pastor to organize and lead the nascent church. In the absence of an ordained pastor, he led, instructed, baptized and encouraged.

On the other hand, Riffel showed a persistent and steady love for the salvation of people he met, and many times his efforts were crowned with success. Juan Riffel, his nephew, stated that Jorge Riffel financed his trip from Russia to Argentina, a cost Juan gave back with years of work. But besides helping financially his nephew, Riffel tried to convince him time and again of the truth of Adventist beliefs. In the words of Benjamín Riffel, his grandson, Juan Riffel said years later:

I also wanted to leave Russia and go to Argentina, but did not have enough money. Your grandfather sent me a thousand pesos that were enough to pay for the trip I did in 1906. I gave that money back working. I was two years with him as farmhand. Any time it was good or there was an opportunity, your grandfather talked to me about the truth. I was a Protestant and had my convictions and would not accept it. But he kept doing his part with unrelenting perseverance. One day I told him: “Grandpa, just leave me alone.” And tactfully, with love and firmness he answered: ‘To him who knows to do good and does not do it, to him it is sin’ (James 4:17, NKVJ). He quoted the text and told me where to find it. That made me think and I reacted favorably accepting the truth”. And he added: ‘Today I am thankful for all he did for me”.27

Likewise, Kimmel, from the Centenario Church, Entre Ríos, shared a talk he had with Jorge Riffel and that confirmed his persistence in sharing his faith with every person he could. In the words of Benjamín Riffel, he would have said:

Your grandfather always talked to us not only about the message, but also about the goodness of the fertile lands in Kansas, United States. He said: ‘We sowed wheat and corn there, that yielded abundant crops, to the point that we picked corncobs the size of my forearm and a few meters away there were oil wells.’ One day I asked him: ‘Since you were doing so well in the United States, why did you come to Argentina?’ He answered emphatically: ‘I came because I knew you needed to know the truth.’ I became an Adventist largely because of him and he was who baptized me and my wife. You have had a great grandfather, because he loved souls and made the best for them to accept Christ.28

Regarding the economic cost of the missionary enterprise carried out by Riffel and the other three families from the USA, a North American missionary asked him once whether he had lost considerably economy-wise with the move to Argentina. Riffel answered he had had a financial setback for several years, but finally had managed to possess more than he had in Kansas before leaving. Actually, Riffel was the first resident to own a motor vehicle in his neighborhood, what was seen by the inhabitants of the zone as a sign of great prosperity. On the other hand, this mission project, according to the same person, had been a big step of faith in the Testimonies of Ellen G. White about the need of volunteering as self-supporting missionary to advance the Adventist cause in the world among other cultures for those that had command of other languages.29

Finally, Riffel is seen actively supporting the establishment of church institutions. First, the foundation of a college and two years later a sanitarium. Although these institutions were promoted by the missionaries of the church, Westphal and Habenicht, without the financial support of the prosperous families of the Adventist community in Entre Ríos, they would have never been a success.

Conclusion

Daniel Oscar Plenc affirmed that although Riffel was short, enthusiast, restless, extroverted and excellent preacher, he was a spiritual giant if measured by the abundant fruits of his evangelizing work.30 There is no doubt that he felt the calling of lay pastor that drove him to this work. However, it must be highlighted his pioneer vision and leadership skill in organizing the Adventist church among the Germans of the Volga. He also represents well the Adventist families that used their financial prosperity to support and strengthen the beginnings of Adventist institutions in Argentina, institutions that have been of enormous importance in the formation of future church workers and in the diversification of evangelistic methods. His life of efforts and achievements in the beginning of the establishment of Adventism in Argentina is an inspiration for new generations that work to finish the proclamation of the soon coming of the Savior.

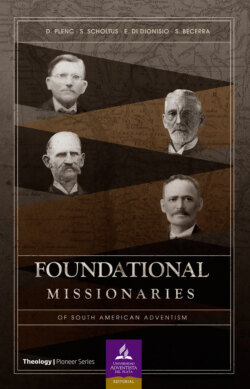

Jorge Riffel (right) with his son David, Julia Weiss, wife of David, and grandchildren.

1 Geörg Riffel, usually known as Jorge Riffel, since documents and usage among Adventists systematically hispanize his name. This article will follow this tradition.

2 The emigration of Germans to the Volga region, in the south of the Russian Empire, took place from 1763 thanks to edicts by Empress Catherine II, the Great, of Russia that offered several privileges to those willing to settle in the Saratov region by the Volga River. Immigration was sustained by approximately 100 years. The interest to migrate from Germany was favored by the hardship provoked by the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and then by the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). The new migration, this time from Russia to America, took place from 1872 caused by the loss of exemption from military service, the lack of land for descendants and a policy of Russification. Brazil and Argentina offered favorable conditions to attract German immigrant from the Volga. In Argentina, a significant group of settlers founded five villages in the department of Diamante, Entre Ríos, on July 21, 1878. One of them was Aldea Protestante, where Reinhard Hetze settled, the first native German of the Volga Adventist. Cf. Víctor Pedro Popp and Nicolás Dening, Los alemanes del Volga (Buenos Aires, AR: Gráfica Santo Domingo, 1977); and Jacob Riffel, Die Russlanddeutschen insbefondere die Wolgadeutschen em La Plata (Argentinien, Uruguay und Paraguay) (n.p.: n.e., 1928).

3 It was the case of the beginning of Adventist missions in Europe. Although the work of J. N. Andrews (first official Adventist missionary) began among the Adventist believers of Tramelan, fruit of the preaching by M. B. Czechowski, a former Catholic priest convert to Adventism. Andrews worked in the French- and German-speaking Protestant Switzerland. The headquarters of the church was established in Basel, a Protestant city. Another Canadian missionary worked among the Waldenses of Piedmont [Cf. J. N. Loughborough, The Great Second Advent Movement: It’s Rise and Progress (Washington, DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1905), 404-406]. There is also a curious incident where Andrews, at the beginning of his work in Switzerland, found out about a group Sabbath-keepers in Germany and visited them intending to integrate them into the Adventist Church. Cf. Historical Sketches of Foreign Missions of the Seventh-day Adventist (Basel, CH: Imprimerie Polyglotte, 1886), 17-21.

4 It was the case of the first interested persons and converts of Davis and Bishop in Chile, and Snyder, Stauffer and Nowlin in the Río de la Plata (Cf. the chapter of this work about Thomas Davis and the thesis by Brown, “A Historical Study of the Seventh-day Adventist in Austral South America”, chapter 4: “The First Colporteurs and the First Minister: 1891-1894”, especially pages 54-61; see also the article by Claudio Fabián Flores, “Inventando a los adventistas: El proceso de invención y reinvención de la identidad en la comunidad religiosa de Puiggari [Inventing Adventists: The Process of Invention and Reinvention of Identity in the Religious Community of Puiggari]”, available at: http://www.naya.org.ar/congreso2004/ponencias/fabian_flores.htm (accessed on October 19, 2011).

5 Diccionario alemán-español, español-alemán (1978), see “riffeln.”

6 “Descendientes de Juliana María Weiss y David Riffel” (unpublished document).

7 Ibid.

8 In these settlements the MIR-DUSCH system was applied, that made the community and ultimately the crown the owner of the land and not the individual. Land was divided and allocated for farming according to the number of males in the community. Every ten years, lands were reallocated by lot, but with the growth of population the hectares belonging to each one were significantly reduced. Initially, each male received approximately 15.5 has. By 1914 this amount had been reduced to 1.9 has. (Popp and Dening, Los alemanes del Volga, 60-63).

9 Ibid., 137-139.

10 This initial group of settlers, Germans of the Volga, was known as La Colonia General Alvear, that corresponded to the simultaneous foundation of five villages of Germans of the Volga in the Department of Diamante, Entre Ríos, on July 21, 1878. These villages are Aldea Valle María (or Marienthal), Aldea Spatzenkutter, Aldea Salto (or Kehler), Aldea San Francisco (or Pfeiffer) and Aldea Protestante (“Nuestra historia: fundación de aldeas [Our History: Foundation of Villages]”, Voces del Volga, available at: http://vocesdelvolga.com/ FUNDACION%20ALDEAS.htm (accessed on October 19, 2011).

11 Robert G. Wearner, “The Riffels: planting Adventism in Argentina”, Review and Herald 61, No. 37 (Sept. 13, 1984): 4-6. Wearner is enthusiast in his report, but his statements about the date of opening of Hillsboro and Lehigh churches by 1888 could not be verified. On the contrary, a search in the Review and Herald in the 1880s shows that since 1884 the work was already systematic among the Germans in Kansas and by 1888 those churches were firmly established. Conradi traveled periodically to Kansas to collaborate in evangelism during the whole decade. Cf. R. Conradi, “Kansas: Leehigh and Hillsboro, May 14”, Review and Herald 61, No. 22 (May 27, 1884); 13; J. W. Bagby, “Work among the Germans in Kansas”, Review and Herald 65, No. 15 (April 10, 1888): 13; H. Shultz, “The Work Among the Germans”, Review and Herald 67, No. 12 (March 25, 1890); 12.

12 See note No. 16.

13 F. H. Westphal, “The Argentine Mission Field”, The General Conference Bulletin 4 (April 15, 1901): 245.

14 There is a family tradition among the Riffels that affirms that the wife of R. Hetze was making bread dough on the Friday Riffel arrived. After studying and deciding together that from then on they would keep the Sabbath, she threw the dough she had leavened to bake that night to the animals as a sign of her new commitment with the day of the Lord (see “Descendientes de Juliana María Weiss y David Riffel”).

15 According to an oral report about the title deed of that time for that place.

16 Hetze, “Cómo empezó la obra en Entre Ríos”, 16.

17 J. W. Westphal, “The Beginnings of the Work in Argentina”, Review and Herald 97, No. 33 (Aug. 12, 1920): 6.

18 Interview to Arístides Riffel, great-grandson of the biographer, by the author in 2009.

19 F. M. Wilcox, “Report of Foreign Mission Secretary”, The General Conference Bulletin 1 (Feb. 20, 1895): 260; E. W. Snyder, “The Work in Argentina”, The General Conference Bulletin 1 (March 4, 1895): 461.

20 L. C. Chadwick, “República Argentina”, La Revista Adventista 69, No. 41 (Oct. 18, 1892): 11.

21 L. C. Chadwick, “Foreign Mission Board Appointments”, Review and Herald 71, No. 24 (June 12, 1894): 11; “South America”, Review and Herald 71, No. 28 (July 10, 1894): 5.

22 Ibid.

23 Westphal, Hasta el fin del mundo, 4. This work is the autobiographical translation by Westphal narrating his years of work in South America, written in the 1920s (Westphal, Pioneering in the Neglected Continent).

24 Ibid., 6-7.

25 Ibid., 7.

26 Hetze, ¿Cómo empezó la obra en Entre Ríos?, 16. Hetze stated that the converts achieved by the arrival of Wesphal, about 120, were divided among the congregations of Diamante and Ramírez. It is not clear from that article whether the Ramírez Church is the same as Crespo Campo. It is most probably so. Anyway, the Diamante Church could be a reference to the group of converts of Camarero, place where the Adventist College and Sanatorium would later be established.

27 Riffel, Providencias de Dios…, 195.

28 Ibid., 195-196.

29 W. A. S., “How the Light of the Advent Message Came to South America”, Review and Herald 83, No. 19 (March 10, 1906): 4.

30 Plenc, Misioneros en Sudamérica, 21.