Читать книгу 250 Days - Daniel Storey - Страница 6

DAY 1

Оглавление‘Go on, Cantona, have an early shower’

At 8.57 pm, Steve Lindsell got the shot.

Lindsell had gone to Selhurst Park on a Wednesday evening to watch Manchester United try to move to the top of the Premier League and witness the third anniversary of Eric Cantona’s arrival in English football through the lens of his camera. He was positioned on the touchline, primed. He would hope to sell a few choice photos – a goal celebration, frustration etched onto a contorted face, a manager thrusting his hands in pockets to protect against the cold January night – to several media outlets.

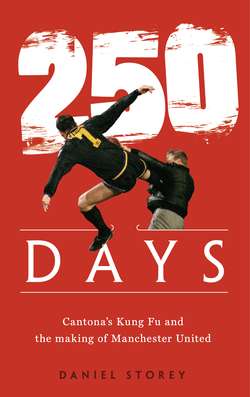

Right place, right time. Midway through the second half, Lindsell hurriedly clicked his shutter and took the photos that captured the most outrageous moment of the Premier League’s first decade. The most famous footballer in the land had both feet off the ground. One was planted into the chest of a supporter. Around him, fans who had rushed to the ground after work, or paced the same walk from their homes as they had done a hundred times before, watched on. Just another home game had become a match they would never forget.

‘I snapped, and snapped again,’ Lindsell said. ‘I thought I had a good picture but couldn’t imagine the impact it would have. I went to my van outside Selhurst Park, printed the roll, which must have taken me 15 to 20 minutes, then sent the pictures. It was only the day afterwards that all hell broke loose.’

Before the 48th minute Cantona had been a passenger in an uneventful game. Palace, just outside the relegation zone on goal difference, had broken up play effectively and limited Manchester United to a series of half chances. This was largely due to the man-marking job done on Cantona by Palace central defender Richard Shaw, who had been instructed by manager Alan Smith to stay touch-tight to the Frenchman.

Smith and Shaw would later insist that the defender was merely doing his job, but Cantona spent the first half complaining about the physical treatment that referee Alan Wilkie had either failed to spot or chosen to ignore. The reality is that Shaw left his foot in on more than one occasion to both put Cantona off his game and try to rile the Frenchman. It was common practice at the time; the hallmarks of the old First Division hadn’t quite been erased.

Wilkie remembers Cantona chastising him as the players left the field at half-time – ‘No yellow cards!’ – and the Frenchman repeating the message as the players waited in the tunnel to come back out for the second half. But, as ever, it was Ferguson’s message that most stuck in Wilkie’s mind. ‘Why don’t you do your fucking job?’ was the Manchester United manager’s presumably rhetorical question. This was par for Ferguson’s course.

What is certainly true is that Ferguson had spoken to Cantona in the dressing room at half-time to warn him not to get involved in Shaw’s games. ‘Don’t get involved,’ he quotes himself as saying in his autobiography. ‘That is exactly what he wants. Keep the ball away from him. He thinks he is having a good game if he is tackling.’

As an experienced – and very capable – central defender, seeing Cantona’s frustration was only likely to make Shaw step up his strategy. You could hardly blame him. Palace could not hope to contend with United on ability.

‘It was all Shawsy’s fault as well,’ Shaw’s teammate John Salako later said with his tongue inserted in cheek. ‘Richard was the best man-marker ever. He had a job to do on Eric and he did it so well Eric got so frustrated he literally booted Shawsy up the arse. Eric lost the plot.’

Three minutes into the second half, Peter Schmeichel launched a goal kick forward and Shaw and Cantona clashed again. Shaw was certainly the first to commit an offence – the linesman flagged to indicate as such – but it was Cantona’s kick-out at Shaw that earned the wrath of the officials. It clearly constituted violent conduct, and Wilkie was left with no choice but to show Cantona a red card. On the touchline, Ferguson was incandescent with anger.

Later, in court, Cantona would accept Wilkie’s decision to send him off but complained at his treatment by Shaw. ‘In my opinion, his decision was correct,’ he said in a statement read out by his barrister David Poole, ‘although I had been repeatedly and painfully fouled in the course of the match.’

One of the direct results of the Cantona incident was that the rule was changed regarding post-red card events. Until the end of the 1994/95 season a player in English football would leave the field at the nearest point following their dismissal. Then followed what was a potentially long walk around the perimeter of the pitch to the tunnel, often passing large swathes of opposition supporters who had free rein to offer their own personalised farewell messages. From August 1995 onwards, players left the field in a direct line towards the tunnel. In hindsight, it is extraordinary that it was ever different.

It does not condone Cantona’s subsequent actions, but the atmosphere at Selhurst Park was notoriously raucous and there is no doubt that any opposition player making the walk in front of the Main Stand would have faced many hundreds of taunts and foul-mouthed tirades.

But for Cantona, that abuse was worse than usual because of who he was, where he came from and which team he played for. Twice Cantona can be seen looking up to the stands in response to particular fans, but after a momentary pause he walks on.

‘It wasn’t just the tackles and shirt pulling he had to deal with that night that pushed him over the edge,’ said then-teammate Gary Pallister in 2015. ‘It was the culmination of a lot of abuse Eric had to put up with at every ground he went to.

‘You wouldn’t believe the kind of vile verbal abuse that was directed at him when we arrived at opposition grounds and got off the bus. Even when we went to the horse races, Eric couldn’t escape it. I remember at one race meeting he was being spat on from a balcony in the enclosure above where we were standing. He was a target, there was no doubt about it.’

One of those supporters delighting in Cantona’s ignominious and premature departure from the pitch was 20-year-old Matthew Simmons. Eye-witnesses said that Simmons had rushed down 11 rows of the Main Stand in order to get as close as possible to the Frenchman to abuse him, though Simmons would later claim that he was merely leaving his seat to visit the toilet.

The language Simmons used is also open to interpretation. Rather comically, he claimed to police in a follow-up interview that he had used the words ‘Off, off, off. Go on, Cantona, have an early shower.’ A slightly different account was heard in court by a witness attending the game as a neutral, and who quoted Simmons as shouting, ‘You fucking cheating French cunt. Fuck off back to France, you motherfucker. French bastard. Wanker.’

It is worth noting that the court sided with the witness and that Simmons’s evidence was clearly unsound, to the extent that even Cantona’s prosecutor Jeffrey McCann fully agreed on that point. It later transpired that Simmons had a conviction for assault with intent to rob and was a British National Party and National Front sympathiser. There is also a theory that Simmons was not even a Crystal Palace supporter, but a Fulham fan who for some reason had chosen to attend the game. On that point, the truth will surely never be known.

Cantona had been subjected to a series of racist taunts and the strongest verbal abuse from someone intent on provoking a reaction. If Shaw was the star in Act 1 of The Temptation of Cantona, Simmons took over the role in Act 2.

Simmons would cause greater controversy having been found guilty of using threatening words and behaviour during the Cantona incident, earning him a £500 fine and a 12-month football banning order. When he appeared for sentencing, Simmons leapt over the bench and kicked and punched the counsel for the prosecution. It earned him a seven-day prison sentence for contempt of court. As he was led away, Simmons shouted a final parting message: ‘I am innocent. I swear on the Bible. You press. You are scum.’

Whatever was said, Cantona’s reaction was shocking. Pausing for a second to identify his target, the forward launched a flying kick at Simmons’s chest and connected emphatically. Falling awkwardly to the floor – as is inevitable when you have propelled yourself near horizontally in such a manner – Cantona then waded in with multiple punches as Simmons fought back. Around them, Palace supporters watched on in astonishment and fear.

Cantona’s teammate Paul Ince also got involved; scalded with hot tea thrown from someone in the crowd, he responded with punches of his own. It was Manchester United’s kit man Norman Davies, tasked with escorting Cantona to the tunnel, who eventually dragged the Frenchman away with the help of a steward. Schmeichel raced over to try to calm Cantona down. It is interesting to see the goalkeeper pointing at the Palace support in an accusatory manner even in the midst of what had just occurred.

Back at the scene of the fight, Manchester United players gathered near the home supporters to vent their displeasure at the abuse that they believed had been responsible for sparking the furore. In front of them, a row of stewards wearing hi-vis jackets provided a human barrier between fans and players. The entire incident lasted seven seconds. Its ramifications would last for years.

‘I just stood there transfixed,’ Pallister told the Manchester Evening News. ‘I was in total disbelief at what I’d seen. I just couldn’t believe it. I can remember seeing Norman Davies attempting to stop Eric beating the living daylights out of the fan. Thank goodness he managed to pull him away.’

Kitman Davies deserves great credit for his pacifying role. Having eventually frogmarched – weak pun unintended – Cantona down the touchline without further incident and got him into the safety and sanctity of the away dressing room, Davies’s job was not finished. He guarded the door from the inside, blocking a still irate Cantona from breaking out and continuing the altercation.

‘He was furious,’ Davies recalled. ‘He wanted to go back out again. I locked the door and told him, “If you want to go back out on the pitch, you’ll have to go over my body and break the door down.”’

Having finally relented, Cantona drank a cup of tea that Davies had made for him and went for a shower. United’s kitman had prevented a dire situation getting even further out of hand. He would thereafter be known as ‘Vaseline’ among the players, having seen Cantona slip out of his grasp to kick Simmons.

The first official reaction to the incident came from Chief Superintendent Terry Collins, who said that Cantona and Ince would be allowed to travel home but should expect to be called to police interview within the next 48 hours. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it in my life,’ Collins said. ‘There could have been a riot.’ On that point, it was hard to disagree.

That same evening, the Football Association issued its own statement: ‘The FA are appalled by the incident that took place by the side of the pitch at Selhurst Park tonight. Such an incident brings shame on those involved as well as, more importantly, on the game itself.

‘The FA is aware that the police are urgently considering what action they should take. We will as always cooperate in every way with them. And as far as the FA itself is concerned, charges of improper conduct and of bringing the game into disrepute will inevitably and swiftly follow tonight’s events. It is our responsibility to ensure that actions that damage the game are punished severely. The FA will live up to that responsibility.’

Ferguson’s reaction was altogether more interesting, not least because he had not seen the full extent of the incident from his vantage point and had been given mixed messages about what had taken place. A number of Manchester United players have recalled their surprise at Ferguson’s composure in the dressing room after the match, barely focusing on the incident but instead castigating his defenders for allowing Gareth Southgate to score a late equaliser. That gives some credence to the theory that United’s manager was not fully aware what had happened. It would have been a brave player to have spoken up to explain.

Ferguson’s initial anger was at Cantona’s stupidity in ignoring his half-time advice. ‘Not for the first time, his explosive temperament had embarrassed him and the club and tarnished his brilliance as a footballer,’ Ferguson wrote in Managing My Life. ‘This was his fifth dismissal in United colours and, in spite of all the provocation directed at him, it was a lamentable act of folly.’ That description became mistakenly attributed to the kung-fu kick at Simmons; it was actually in reference to the kick on Shaw.

Initially – and, his critics might say, typically – Ferguson blamed the referee. Alan Wilkie had also not seen the incident, although he was informed post-match of the precise details and stayed late at the ground to assist with the initial inquiries. He was met by a furious Ferguson, who told him, ‘It’s all your fucking fault. If you’d done your fucking job this wouldn’t have happened.’ It is unclear whether Ferguson was again referring to the red card or the post-sending-off events, but a police officer eventually had to force Ferguson out of Wilkie’s dressing room.

Having flown back to Manchester late that night, Ferguson rejected the advice of his son Jason to watch what he described as a ‘karate kick’ and instead endured some broken sleep. By 4 am he had risen, and by 5 am was ready to watch the footage. ‘Pretty appalling,’ is the only description that Ferguson offered.

Ferguson’s anger with Cantona reflected his disappointment that he had been so let down by a player in whom he had bestowed considerable faith. Manchester United had been widely derided for taking a chance on the enfant terrible. If Cantona’s performances in his first two seasons had proved Ferguson right, here was the sting in the tail.

Manchester United’s manager couldn’t say that there had been no warning signs. When playing for Auxerre, Cantona punched teammate Bruno Martini after a disagreement. During a charity match in Sedan for victims of an earthquake in Armenia, he kicked the ball into the crowd, threw his shirt at the referee and stormed off the pitch. In September 1988 he called France national team coach Henri Michel ‘a bag of shit’ in a post-match interview and was banned from playing for the national team until after Michel’s eventual sacking.

In 1991, when playing for Nîmes against St-Étienne, Cantona threw the ball at the referee and was given a four-game ban. When hauled in front of a disciplinary commission to explain himself and be told that other clubs had complained about his behaviour, Cantona approached the face of each member of the panel and called each of them an idiot in turn. The ban was promptly extended to two months.

That ban led to Cantona retiring from football at the age of 25, but he was talked round by Michel Platini, who believed that such a talent was too big a loss for the national team. It was Platini who persuaded Cantona to consider a move to England, having burned his bridges in Ligue 1.

If Ferguson’s aim was to smooth the roughest edges of Cantona’s ill-discipline, he barely managed it. Six months after joining United, Cantona was found guilty of misconduct and fined £1,000 after Leeds United fans accused him of spitting at them. Cantona claimed that he had spat at a wall. The disciplinary commission certainly agreed that there were mitigating circumstances, Cantona having been subjected to constant abuse from Leeds supporters.

In 1993/94, his first full season at Old Trafford, Cantona was sent off twice in the space of four days against Arsenal and Swindon. The first dismissal was for a stamp on the chest of John Moncur, the second for two yellow cards. The accusation against Ferguson’s United was that they were becoming undermined by their own indiscipline. For better and worse, the players were following Cantona’s lead.

Matters deteriorated even further in September 1994 in Galatasaray’s Ali Sami Yen Stadium, a daunting atmosphere for any player. Cantona was again sent off, right on the full-time whistle, and was reportedly struck by a police officer’s baton as he headed down the tunnel. Incensed by the assault, Cantona attempted to force his way through stewards and officials to confront the police officer, and had to be dragged to the dressing room and guarded by teammates.

‘Pally [Pallister], Robbo [Bryan Robson] and Brucey [Steve Bruce] had to drag Eric in and hold him there,’ Gary Neville remembers in his autobiography. ‘The experienced lads were going to the shower two by two so that Eric was never left alone in the dressing room. They ended up walking him to the coach to stop him going back after the police.’

This suggests two things: that Cantona’s combustibility was hardly a secret to Manchester United’s coaches and players, and that his anger took a considerable time to dissipate.

The uncomfortable truth for Ferguson is that Cantona was an accident waiting to happen and that the incident at Selhurst Park – while initially shocking – was not at all surprising. Manchester United’s manager backed himself to curb such ‘over-enthusiasm’ but was not successful, even if he rightly considered that Cantona’s quality outweighed the pitfalls.

In an interview with the Observer in 2004, Cantona – perhaps unwittingly – alluded to the inevitability of such incidents and his own lack of control. ‘If I’d met that guy on another day, things may have happened differently even if he had said the same things. Life is weird like that. You’re on a tightrope every day.’

Further evidence arrives in another Cantona quote, this time on the subject of being challenged. ‘I want to be like a gambler in a casino who can feel that rush of adrenaline not just when he’s on a roll, but all of the time,’ he said. ‘He gambles because he needs that buzz, he wants to experience it every moment of his life. That’s the way I want to play.’

This is the definition of playing on the edge, with every extreme element of the psyche bubbling just beneath the surface. It is a style that is rarely admitted to by sportspeople, for whom the typical strategy to achieve excellence is to rely upon an inner calm that enables composure in the crunch moments.

Cantona was a team player and very rarely selfish in possession of the ball, and yet he says that penalties – football’s most individual moment – were his ultimate buzz because they offered him a few seconds during which all eyes were on him to perform. He was driven to achieve, not necessarily to help the team or for personal glory, but through an addiction to the feeling of displaying immense skill and entertaining spectators in doing so.

That might sound peculiar, but it’s actually a persuasive argument. Becoming a professional footballer and maintaining your fitness and level of performance is incredibly hard. Dragging yourself through such physical and mental exhaustion for neither money nor love but to satisfy an addiction makes some sense. After all, many retired players speak of their propensity to succumb to other addictions because of their need to recreate football’s adrenaline rush.

Cantona sat at the extreme end of that spectrum. Anything that stopped him playing or curtailed his enjoyment of the game became the enemy: referees with their red cards, defenders with their physical treatment, coaches with their stymied tactics, supporters with their abuse. All this explains his fury in Istanbul and south London.

Cantona’s desire to ‘feel that rush’ blended with an anarchistic edge to his personality that lay not in a mistrust of authority per se, but a need to enjoy freedom of expression. ‘Above all I need to be free,’ he writes in Cantona on Cantona. ‘I don’t like to feel constrained by rules or conventions. There’s a limit to how far this idea can go, and there’s a fine line between freedom and chaos. But to some extent I espouse the idea of anarchy.’

Rather than rules, Cantona preferred to administer justice according to an ethical code; one that his critics might argue lacked calibration. So when Simmons screamed xenophobic abuse in his face, Cantona’s temper and determination to dispense moral retribution led to a spectacular assault. The accusation from Simmons that Cantona was a ‘lunatic’ was spectacularly misplaced.

Amid the myriad explanations for the attack, one thing remains certain: Cantona stayed true to his principles and never regretted his actions. ‘I’ve said before I should have kicked him harder but maybe tomorrow I’ll say something else,’ he said in 2017. ‘I cannot regret it. It was a great feeling. I learned from it – I think he [Simmons] learned too.’

Had you spoken to Ferguson on the morning of 26 January 1995, he might have had a slightly different view. Manchester United had travelled south to Selhurst Park with the chance to go top of the Premier League. They travelled back north without a victory, with potential criminal charges hanging over two key players and with their most talented attacker once again thrust into disciplinary controversy. Lock the doors and windows and batten down the hatches at Old Trafford. A storm was brewing.