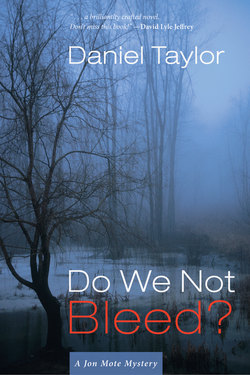

Читать книгу Do We Not Bleed? - Daniel Taylor - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

three

ОглавлениеI claimed to be better, but I’m thinking that maybe I’m only different. As I say, the voices haven’t come back as yet, though they’ve orbited away before, only to return. But I’m not so much worried about that. It feels like maybe they’re gone for good this time. The question is, “What takes their place?” They filled a space that now is simply a void. It does little good to get rid of an evil if you don’t replace it with a good. There are plenty of other doubtful things to rush back in. (There I go again, using the exhausted terms of bankrupt ideologies—good and evil, and their siblings true and false, beautiful and ugly. Hopelessly binary. Spray all the herbicide you want, some dandelions keep coming back.)

“More purposeful action,” I claimed. (I love quoting myself.) But action for what purpose? Action without purpose is just activity—Brownian motion. And purpose has to be deeper than survival, than outlasting the circling sun of another day. There needs to be at least a baseline purpose for living, on which the merely pragmatic purposes of this minute and that are set. Don’t you think? (I’d be a heck of a philosopher if I could just develop the philosophical squint.)

No voices, yes, but silence instead. Is that progress? The big threat now is not Disintegration but Normality. Normal—the usual coupled with the meaningless. Alive but trivial. A brief coalescence of electrified matter, soon dispersed. Coagulated pointlessness. Why hang around?

I depress myself. (Therefore I am?)

I got my first taste of Being with Specials in Public only a few days after starting work at New Directions. In an upscale public space no less. You might say it was in obedience to a government mandate, but that requires a bit of explanation.

Government is a wonderful contraption. I think of it as a vast system of interconnected feeding troughs—as in a stockyard. Every branch, bureau, agency, center, department, headquarters, and office gets a trough. And each trough is presided over by a politician, manager, director, chief, supervisor, administrator, officer, controller, overseer, inspector, examiner, or head. All of whom need assistants, underlings, lackeys, workers, enforcers, advisors, consultants, counselors, subordinates, associates, aides, and, of course, secretaries. Needless to say, every one of these people needs offices, furniture, machines, transportation, security, heat and light, computers, and, not unimportant, wall art. Of course “trough” is too static a metaphor to describe what is more an organism than a contraption. These are neuronic troughs, each one connected synaptically to its next closest trough, like cellular structures in the brain, the whole growing day and night, each one eternal and eternally expanding. In such a system the whole point of existence—for bureaucrats and for citizens—is to get access to one of these troughs. And then to feed.

Which is why the residents and I were heading to the theatre. (Dr. Pratt, my deconstructed grad school mentor and erstwhile life coach, would be proud of me for this brilliant analysis.)

For you see, each of the residents is supported by a program, a title this or a title that. And programs administer troughs and therefore require budgets. And budgets require numbers, including numbers for money spent. So each client is a part of the budget of New Directions, and New Directions has informed Government that dollars X are necessary to spend for the entertainment of resident Y, entertainment being a necessary part of the life of a Special, just as it is for a Normal Human Being. And if that entertainment money (better to call it “programming”) is not spent on client Y, it will not be in next year’s budget, which is not good for New Directions or for client Y.

So Cassandra said to me a few days after I began, “Ralph’s account is getting too big. Buy him something—a new area rug or lamp or radio . . . anything. And take everyone out on an activity. Anything. We’ve got a report due at the end of the month and we’ve got to show more spending.”

I don’t think she really wanted to say it exactly like that. She was thinking out loud. She caught herself and looked at me like we were standing next to a cookie jar and she was holding a macaroon.

“You know what I mean.”

Yes, I knew exactly what she meant. Feed at the trough. Keep the slop coming. Oink. Oink.

So we little piggies went to market. High-end market. The Guthrie Theater, in fact. Tyrone’s palace across the street from Loring Park and next to the Walker Sculpture Garden. It was December, and at the Guthrie December means A Christmas Carol, as it has for something like twenty-five years now. Zillah and I had season tickets for the Guthrie for the first stretch of our time together. It was a nice break from a troubled marriage to go see something like The Oresteia or Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (This is called irony. I learned it early and it has been my loyal companion lo these many years.)

I’ve been thinking about Zillah a lot lately. It’s easier to keep away from someone physically than to keep them out of your thoughts. I haven’t seen her for more than a year, closer to two, but she pays regular visits to all three sections of my Freudian brain—id, ego, and superego. The psych folks have pretty much junked Freud, but I still like the simplicity of the cancer-jawed old geezer. (Did the gods afflict him for telling us lies, or was it just random bad luck?)

How is it that I miss being with a woman with whom I mostly gave and received pain? (“Why should I blame her that she filled my days / With misery?”) Maybe it’s that the pain did not lessen when we parted, but the sense of being in something significant together did. Or maybe not.

We arrive for our matinee performance. (Specials, with a lifetime of scheduled bedtimes, tend to turn into pumpkins at around 9 p.m., so afternoon activities work better.) It’s crowded in the big lobby, which serves both the Guthrie and the Walker Art Center. Dickens’s occult, moralistic thriller is the Guthrie’s dependable cash cow. Parents love to bring their children to it (moooo!), never mind that it scares the bejesus out of the younger ones and bores the older kids (who consume slasher movies like popcorn).

The residents stick close to each other and to me, the primal herd instinct when danger (read “the unfamiliar”) is in the air. Bonita stirs things up a bit.

“Watch out!”

She’s points straight up and everyone follows her finger and then crouches down as if death is descending from the sky.

“What the hell is that?”

That, it turns out, is art. An Oldenburg to be specific. A huge, plasticky, leathery, saggy, artsy rendering of an everyday three-way electrical wall plug to be exact. It’s the size of a minivan and hangs over the crowd from the ceiling, looking more than a little forlorn.

“It’s art,” I say.

“Noah’s ark?” Jimmy asks.

“No, art. With a ‘t’.”

It’s Judy’s turn.

“Why, why, I . . . I should say, I like ar . . . art, Jon. It’s . . . it’s very pretty.”

Billy is looking up, but then Billy is always looking up, so I don’t take it as a sign that he has suddenly developed an interest in oversized aesthetic wall plugs. Billy is as Special as they get, and he communicates, if at all, with things beyond the ken of Normals and Specials alike.

Ralph, as usual, is unimpressed. He shoots a glance and sums it up for the group with a wave of the hand.

“Ah phooey.”

Everyone seems satisfied with that and we move on.

Moving on means getting in line at the Will Call window. I’ve made reservations but there wasn’t time to mail the tickets, so we have to pick them up. It’s a long line.

I place myself in the middle of our group, all of us single file. I’d have them wait for me separately but there’s no telling where these sheep will go if the good shepherd ain’t among ’em. I’m a little self-conscious about having brought them all to the Guthrie. A ballgame or bowling alley is one thing. But a squad of Specials is more than a little unusual at a chic cathedral for the performing arts. (Not that the management wouldn’t be thrilled at this unplanned diversity moment. Play it right and we could end up in an ad campaign—“Differently Abled Enjoy a Night at the Theatre.”)

I’m looking back toward Judy and Ralph holding hands at the back of our little group when I hear a familiar voice and sounds of commotion in front of me. Bonita has gotten tired of waiting and is suddenly pushing her way through the people ahead of us in line toward the ticket window, Jimmy right behind her.

“Let us through, we’re retarded,” she yells, her head down like a running back plowing into the scrimmage line, looking for a hole.

People are parting like the Red Sea.

“Let us through, we’re retarded!” she repeats.

My God, the R word. In public. And in the mouth of one of my charges. My career with the Specials is hanging by a thread.

“Bonita! Jimmy!” I bark. “Get back here!”

I take a couple of big steps and grab the back of Jimmy’s shirt. Bonita continues pushing ahead, delighted with how well things are working out. I am trying to reach for her with my other hand when a purse bounces off the side of my head.

It’s an old woman.

“Young man, you leave these people alone! It’s wonderful that they are here, and I will not have you bullying them!”

Others nod and shoot me Medusa looks. They all step aside and wave for the rest of us to pass up to the front. I am speechless but caught up in the tidal movement of our group toward the window. When I get there, Bonita is waiting for me with an expression of patient resignation.

“Stick with me, Mote.”

We’re in the cheap seats, though none of the seats are actually cheap, which I assume Cassandra will be happy about. Oink. Oink. I wasn’t able to get us all in the same row, so J.P. is by himself in the row ahead of us, right in front of me, so I can keep an eye on him. We’re early and there’s no one else in his row at the moment.

All is well. Everyone localized in a seat. Everyone having gone to the toilet before we left the group home. Bonita calm and satisfied after her Pickett’s Charge to the Will Call window. Jimmy peering all around, sizing up the possibilities. Ralph and Judy blinking rhythmically. Billy starting to hum.

I see a young woman standing in the aisle at the end of J.P.’s row, looking at her ticket and then at the row number. She’s a good twenty seats away from J.P., but hasn’t looked up either at him or at the rest of us in the row behind. She starts walking down the row, marking the number on each seat as she passes it, holding her ticket out in front of her. I see J.P. spot her. His eyes get big. A new friend, which, despite his natural reticence, he collects like baseball cards.

She takes a surreptitious glance at J.P. as she sits down in the seat next to him, but then looks straight ahead. J.P. is looking directly at her left ear, a smile on his face that would shame the Cheshire cat. He twists his head around further and looks at me.

“I’m a lucky guy!” he says loudly.

She shoots out of her seat like a pilot ejecting from a burning fighter jet and flees down the row.

“Oh well,” says J.P. with a shrug.

“Can’t win ’em all, buddy,” observes Jimmy the Man-About-Town.

I can’t tell whether the residents are understanding anything in the play or not. Judy certainly figures out Scrooge in short order.

“He . . . I should say . . . he is not a very nice man.”

And Tiny Tim presents no mystery.

“He’s like Don,” says Jimmy. Don is a kid on the boy’s floor back at New Directions who has cerebral palsy and uses crutches.

“Hello, Don!” Jimmy calls out with a wave. The other residents laugh and Jimmy beams. He’s got this trick down and repetition only burnishes it.

But they don’t seem to know what to make of the ghosts in the play.

Bonita is suspicious.

“I don’t like ghosts,” she says under her breath. “Ghosts are dead people and dead people are yuk.”

This gets nods and general agreement. I try to get everyone to keep quiet, but they are figuring this out together and ignore me.

“They are not . . . are not ghosts, Bonita Marie. They . . . they are called act . . . actors. They are just pre . . . pretending to be ghosts.”

This stumps the group.

“Like on Scooby-Doo,” suggests Jimmy.

“That, that’s right, Jimmy. Like on . . . on Scooby-Doo.”

The troops seem content with that answer and they noticeably relax.

Long before we get to Christmas Future, the residents have lost their zip. After I reject Bonita’s call for popcorn all around, she crosses her arms and sulks silently. Ralph is asleep. Jimmy is snapping his fingers and kicking the back of the seat in front of him. J.P. hasn’t moved a muscle in an hour, sitting straight, shoulders back, staring at the stage but giving no hint that he is following the action, such as it is.

At intermission we are out of there.

The residents offer their usual post-game analysis. Sometimes they are amazingly perceptive, in their Special Kind of Way. After we watched a rerun of Rocky on television one night, J.P. had said, “That was filmed in black and blue.” I couldn’t tell whether he was confused about a statement of fact or trotting out a sly word play. These guys keep you on your toes.

With A Christmas Carol, they seem content to simply catalog the good guys and the bad guys. Maintaining a clear moral order in the universe is important to them, a legacy, no doubt, of the simplified world of the nuns. I got my fill of Sister Brigit quotes when Judy lived with me on the houseboat in St. Paul. Now that I’m working with the older ones at New Directions, I get them in stereo.

As when Jimmy observes thoughtfully, “Sister Brigit would not have let us see that. Christmas is not about ghosts. Christmas is about Jesus.”

Van-wide approval. See if I take you guys to the theatre again.