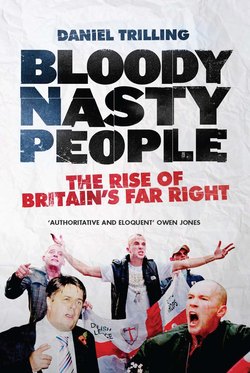

Читать книгу Bloody Nasty People - Daniel Trilling - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

On a spring afternoon in early 2011, I was sitting outside a country pub, when a car pulled up. Out stepped two well-built minders, followed by the portly figure of Nick Griffin, chairman of the British National Party. The BNP has the dubious distinction of being Britain’s most successful far-right party ever; despite roots in a neo-Nazi subculture, it notched up a string of victories in local elections over the past decade, along with two seats in the European Parliament, before an electoral collapse in 2010. It remains an ugly presence on the country’s political landscape, with Griffin periodically invited onto national media to promote the BNP’s racist policies. Yet, for all that, it has been little understood.

I was hoping to find out more. Griffin could not meet me in central London – a ‘security risk’, he had told me when we spoke on the phone – so instead we had arranged to meet here, a few miles outside the Essex town of Epping. (‘Are you a real ale drinker?’ he had asked me. ‘Choose a pub from the Good Beer Guide.’) The trio looked tired and grumpy when they emerged from the car. Because he is so widely despised, Griffin can’t take public transport and so spends hours crammed alongside his hired muscle into a grey hatchback. He speaks ever so slightly too fast, like a man who is used to being heckled or cut off mid-sentence. Since he was elected to the European Parliament in 2009 this semi-fugitive lifestyle has intensified as he makes regular trips across France and Belgium. Griffin, dressed in a dark suit, walked over, shook my hand and sat down; one of his minders nipped inside the pub and returned carrying an unappetizing on-the-road snack: half a Cornish pasty, on a paper napkin, and a packet of dry-roasted peanuts. ‘This is lunch, that’s why I’m not sharing any with you,’ Griffin said, mouth full, as I fiddled with my Dictaphone and searched in my bag for a notebook.

‘So,’ Griffin eventually said, brushing peanut dust from his jacket sleeves. ‘Tell me about this book.’

In April 2008, the New Statesman sent me to review a music festival in East London’s Victoria Park, held to mark the thirtieth anniversary of Rock Against Racism, the cultural movement that had galvanized opposition to the National Front in the late 1970s. My parents, both of whom had gone on anti-racist demos during this period, had told me stories about Rock Against Racism when I was younger, and I was excited to see some of that spirit revisited. It was timely, too: for several years, the British National Party had been growing in prominence, winning seats on a number of councils across England. Elections to the London Assembly, where the BNP was expected to pick up support, were only a few days away.

But something seemed wrong: while thousands of smiling, ethnically diverse teenagers turned out to see the bands, under the slogan ‘love music, hate racism’, it felt strangely detached from reality. Thirty years previously, Victoria Park, in the heart of London’s East End, had been the front line of the fight against the National Front. In 2008, the BNP was gaining support on the outskirts of the capital, miles away from cosmopolitan inner London. The image of its supporters was not that of angry young skinheads, but of pessimistic ex-Labour voters. And surely Britain, too, was a changed place? Hadn’t the battle by black and Asian immigrants to have equal place in popular culture been won? Hate racism? Well, of course – nobody in twenty-first-century Britain wanted to be known as a racist, not even the BNP.

At the time, I could not articulate these thoughts, and my overly cynical review of the festival drew stinging criticism from trade union leaders who had helped organize the event. Praise came from one quarter only: a BNP website that crowed about the party’s seemingly unstoppable rise. A few days later, the BNP candidate Richard Barnbrook was elected to the London Assembly with over 5 per cent of the vote. A relatively small achievement, but another first for a party whose opponents were adamant was a fascist one. ‘Knocking on doors is the secret of our success,’ claimed the website, adding: ‘Our strategy of meeting voters face to face on the doorstep and backing up our campaigns with well produced and easy-to-read election leaflets is providing the right results. There has been much talk . . . of the Labour Party being disengaged from voters – and it is. The BNP on the other hand, through our canvassing, are fully connected.’

‘Fully connected’? What on earth did that mean? And how exactly did a party whose own constitution bore a commitment to ‘reversing the tide of non-white immigration and to restoring . . . the overwhelmingly white makeup of the British population that existed in Britain prior to 1948’ win votes simply by ‘knocking on doors’?

These questions, and more, led me to think about this book. Who are the ‘bloody nasty people’ to whom the title refers? Most obvious are the men (and a few women) who have devoted their lives to fascist and racist politics. They are not foaming-at-the-mouth monsters – indeed, to be so would require far too unstable a temperament for the painstaking and unglamorous work they have put in, over years and decades, towards making the BNP a successful political party. Some may be oddballs and loners; others may be loving parents and partners; and many are gregarious (among the right people, of course). Like most of us, members of the BNP will be a combination of all these things. But they have committed themselves to a politics that even in its ‘voter-friendly’ incarnation would cause untold misery and conflict among the people of this country.

But there is a distinction between committed BNP members and those who have been drawn to support the party. Most – numbering well over a million – will have voted BNP at some point in the past decade. Some will have leafleted or canvassed. A few have even stood for election. There is a persistent image of these people as dejected, racist ‘white working class’. This has been distorted because the image of BNP voters is a powerful tool politically. In some quarters the accusation of bigotry has been a convenient way to dismiss legitimate concerns over jobs and housing. In others, such people have been evoked piously by advocates of a halt to immigration, or by those who proclaim the death of multiculturalism. We will see how this fits into a wider problem Britain has with addressing class, where working-class people have been virtually banished from our politics and media, only to return sentimentalized or demonized according to the occasion. ‘Bloody nasty people’ was a 2004 headline taken from the Sun – and I have used it to raise a question: to what extent have the actions of established politicians, and the mainstream media, given the BNP fertile ground on which to operate? And do the same factors lie behind the more recent emergence of the English Defence League?

Fascism is a heavily contested term: to use it will immediately conjure up images of Hitler and swastikas, or of Mussolini and jackboots. To many people it denotes a particular style of authoritarian politics, located in a historical era that has now passed, and may seem an unhelpful term when discussing the BNP and English Defence League.

For the purposes of this book, I have taken the work of the American historian Robert O. Paxton as my guide. In The Anatomy of Fascism, Paxton explains that while fascist movements throughout the modern period have varied in appearance and tactics, they ‘resemble each other mainly in their functions’. In other words, fascism is not a question of what clothes you wear or what poses you adopt. Rather, as Paxton attempts to define it, ‘fascism is a system of political authority and social order intended to reinforce the unity, energy and purity of communities in which liberal democracy stands accused of producing division and decline.’

This may sound vague at first, but this is because fascism does not offer a fixed set of policies; rather it seeks to recruit followers and bind them around a pole of extreme nationalism by appealing to what Paxton terms as ‘mobilising passions’: fear, betrayal, resentment, a mortal enemy within or without. ‘Feelings,’ he writes, ‘propel fascism more than thought does.’ Those ‘passions’ – the raw material of fascism – are not the preserve of a small group of fanatics, but exist in society at large.

In general, however, I have opted to use the more neutral term ‘far right’ when referring to the BNP and EDL. This covers a range of political positions, from anti-immigrant populism to outright fascism. It will become clear over the course of my argument that the BNP is fascist in origin, and has remained so at heart – but it has been able to progress only by appealing to a wider set of far-right interests. The EDL is an even looser grouping. I use the term ‘neo-Nazi’ only to refer to groups or individuals who seek to recreate the policies, or adopt the visual symbols, of the German Nazi Party. In the BNP’s history, there have been more than a few.

In Britain, the far right has often been portrayed as an aberration, a foreign malady imported into an otherwise tolerant milieu. This has had great strategic value for its opponents: highlighting the Hitler-worshipping tendencies of the National Front’s leaders during the 1970s was an easy way to discredit a supposedly patriotic movement. But this risks obscuring the home-grown intellectual traditions on which parties like the BNP draw. And by regarding them in isolation, we can also miss what they share in common with the political mainstream, the sources from which their propaganda draws its appeal.

As Enoch Powell once remarked, ‘The life of nations . . . is lived largely in the imagination.’ If that is so, then the story of the BNP takes us into the darker corners of this national fantasy. It may force us to confront some unpleasant truths about Britain, but it is vital we overcome our revulsion and examine it carefully: we must peer into its eyes, even if we risk finding ourselves reflected back.

It was getting dark in Essex, so Griffin and I moved inside the pub. Towards the end of our interview, during which the pub had been empty, a couple of men in rugby shirts came in and sat by the bar. After Griffin left (I thanked him politely and told him I hope he never succeeds), one of the men called over: ‘Good luck with the interview.’ Easy to spot I’m a journalist, I suppose. I apologized for having brought Griffin into their pub and explained that he wouldn’t meet me in central London.

‘Fine by me, mate,’ said one in a confident leer. I was puzzled by the ambiguity of that statement – was he happy for his local to be used by journalists? Or was the interviewee more welcome than the interviewer? I didn’t stick around to find out more. I stepped out of the pub with the questions left hanging.