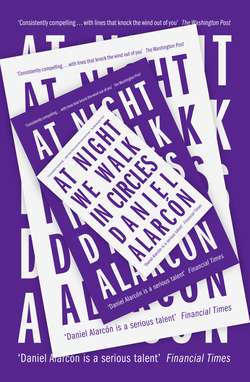

Читать книгу At Night We Walk in Circles - Daniel Alarcon - Страница 12

5

ОглавлениеIN THE FINAL WEEKS before they left the city, Henry began to jot down a few ideas. Notes. Dictums. Data points. Pages of them, from a man who had all but abandoned writing since his unexpected release from Collectors fourteen years before. Later, when we spoke, he shared these folios with me, apologetic, even embarrassed, as if they proved something about the ill-fated tour, or his state of mind in the days prior. I was unconvinced, but I scanned the pages anyway, trying to make sense of them.

A sampling:

Bus was twelve minutes late today, read a line scrawled on a page dated March 16, 2001. Reasons unknown and unknowable. Mystery. Could have driven.

Two days later: Woke to a serviceable erection at 7:00 a.m. Sat up in bed, turned on the light, to observe it. Watched it wilt, like time-lapse photography. My very own nature special. I should have been on television when I was young, before I was ugly. Slept awhile longer. Three eggs for breakfast. No coffee. Pants feeling tight in the thighs. A woman got in the cab today, black hair, asked if I would—

The following week: For seven months, I hardly talked about life outside. Except with Rogelio. Because he asked.

March 27: A play for Rogelio. Finally. A love story. A man learning to read in a rented jail cell. Being taught to read, in exchange for sex. A plainly capitalist transaction, between two men pretending to be in love. Perhaps they are. Awkward moments. Butter as lubricant, stolen from the commissary and warmed between their palms. Between their thumbs and two fingers. Strange that such a simple gesture could be so arousing. A woman got in my cab today, black hair, ruby lips. Asked if I would climb in the back and make love to her—

Then pages of lists: Dead things I’ve seen—telephones, lightbulbs, street corners, nightclubs. Also: pigs, painters, passengers, plays, presidents, prisoners …

On and on like this.

Was Henry losing it?

I don’t think so.

Or—perhaps.

Far worse things have been published as poetry and won awards; which is what I told him, in so many words, as I tried to hand the journal back. He wanted me to keep it. Correction: he insisted I keep it—as if the pages contained something toxic he wanted desperately to be rid of—and I obliged. The important thing for us to understand is this: Henry thought he was losing it, and it worried him. He entered the prison every night in his dreams, walked its dark hallways, inhaled its fetid air. He’d forgotten so many details about his time inside that it terrified him: the color of Rogelio’s eyes, for example. The number of the cell they shared on Block Seven. The meal they shared on the last night before his release.

But every afternoon, at every rehearsal, something struck him, some bit of the past emerging with surprising clarity. Henry began to remember, began to piece things together. This particular play, of the dozen or so he’d written, had special characteristics: it was the last one he’d finished, the one that had brought his career (such as it was) to a premature close. It had last been performed by men who’d died only a few months later, dead men who’d begun to appear in his dreams. Perhaps the script itself was cursed. These men, these ghosts, hovered about the stage at every rehearsal, sat in the ragged seats of the Olympic to critique every line of dialogue. They booed each poorly rehearsed scene, whispered their doubts in his ears. It was impossible not to feel unsteady when confronted with this text. After all, the man who wrote it had lived another life, and that life was gone. That’s what Henry was dealing with. Nelson, unfortunately, and through no fault of his own, had to watch this up close. It wasn’t pretty.

The kicking incident, for example, which Patalarga described so vividly—Henry recalled it too, answering all of my questions politely and without hesitation. He had experienced it this way: a feeling of looseness, a momentary disorientation. Anger. Impotence. Then, an image: in August 1986 he’d seen a man be kicked to death, or nearly to death, by a mob that formed unexpectedly at the door to Block Twelve. He and Rogelio had stood by, at first horrified, then simply frightened. Then, almost instantaneously, they’d accepted the logic of the attack: every victim was guilty of something. The chatter: What did he do? Who did he cross? The men watching felt safer. Less helpless. A crowd had formed around the victim, but no one moved. Henry took Rogelio’s hand. Squeezed.

“Do you see what I mean?” Henry asked me.

I said that I did, but I could tell he didn’t believe me.

Not every memory was poisonous. For example: one day, Henry gathered up his courage, and went to see Espejo, the boss, about doing The Idiot President in Block Seven; surely this was one of his fondest memories. Espejo was a small but well-built man whose lazy grin belied a long history of violence, a man who’d risen far enough from the streets to relax, and now controlled the block through sheer force of reputation. He was languorous and content, occasionally dispensing pointed but very persuasive doses of rage should any inmate question his authority. Mostly though, he protected them—there were less than two hundred men in their block, and after nightfall they were in constant danger of being overrun by one of the larger, more ferocious sections of the prison. Espejo directed a small army of warriors tasked with keeping those potential invaders at bay.

Henry was afraid of this man, but he had to remind himself: me and Espejo, we’re Block Seven, we’re on the same side.

Espejo’s cell reminded him of a small but comfortable student apartment, with a squat refrigerator, a black-and-white television, and a coffeemaker plugged into a naked outlet. Espejo kept a photo of himself from his younger days framed above his bed, an image Henry had never been able to shake in all the years hence. He described it to me: in the picture, Espejo is shirtless, astride a white horse, riding the majestic animal up the steps of a swimming pool, toward the camera. He is handsome and powerful. A few delighted women stand behind him, long-legged, bronzed, and gleaming in the bright sun. Everything is colorful, saturated with tropical light. A child—Espejo’s son, one might guess—sits at the edge of the diving board, watching the horse maneuver its way out of the water. On the boy’s face is an expression of admiration and wonder, but it’s more than that: he’s concentrating; he’s watching the scene, watching his father, trying to learn.

Henry would’ve liked to be left alone with the photograph, to study it, to ask how and when it had been taken and what had happened to each of the people in the background. To the boy most of all. He might have fled the country, or he might be dead, or he might be living in a cell much like this one in another of the city’s prisons. There was no way of knowing without asking directly, and that was not an option. The photo, like the lives of the men with whom Henry now lived, was both real and startlingly unreal, like a framed still from Espejo’s dreams. What did Espejo think about when he looked at it? Did it make him happy to recall better times, or did the memory of them simply hurt?

Rogelio had warned him not to stare, so he didn’t.

“A play?” Espejo said when Henry told him his idea.

Henry nodded.

Espejo lay back on his bed, his shoeless feet stretched toward the playwright. His head and his toes shook left to right, in unison. “That’s what we get for taking terrorists,” Espejo said, laughing. “We don’t do theater here.”

“I’m not a terrorist,” Henry said.

A long silence followed this clarification, Espejo’s laughter replaced by a glare so intense and penetrating that Henry began to doubt himself—perhaps he was a terrorist after all. Perhaps he always had been. That’s what the authorities were accusing him of being, and outside, in the real world, there were people arguing both sides of this very question. His freedom hung in the balance. His future. Henry had to look away, down at the floor of the cell, which Espejo had redone with blue and white linoleum squares, in honor of his favorite soccer club, Alianza. One of Espejo’s deputies, a thick-chested brute named Aimar, coughed into his fist, and it was only this that seemed to break the tension.

“Did you write it?”

Henry nodded.

“So name a character after me,” Espejo said.

Henry began to protest.

Espejo frowned. “You think I have no culture? You think I’ve never read a book?”

“No, I …” Henry stopped. It was useless to continue. Already he’d ruined himself.

They were quiet for a moment.

“Go on. If you can convince these savages,” Espejo said finally, waving an uninterested hand in the direction of the yard, “I have no objection.”

Henry thanked Espejo and left—quickly, before the boss could change his mind.

“I told Rogelio the news, and we celebrated,” Henry said to me.

“How?”

Henry blushed. “We made love.”

“Was that the first time?”

“Yes.” His voice was very soft.

Then: “I don’t remember.”

Then: “No.”

I told Henry we could stop for a moment, if he wanted. He sat with his head at an angle, eyes turned toward a corner of the room. He laughed. “It’s not because we were in prison together, you know. You’re making it sound cliché.”

“I didn’t say that. I’m not making it sound like anything. I’m not judging you.”

“You were thinking it.”

“I wasn’t,” I said.

He frowned. “Are you a cop? Is that what this is?”

I thought I’d lost him. I shook my head. “I’m not a cop,” I said in a slow, very calm voice. But at the time, even I wasn’t sure what I was doing.

“Nelson and I, we’re almost like family,” I said.

Henry’s brow furrowed. “He never mentioned you.”

Silence.

“The play,” I said, after a moment. “Was it easy to get inmates to volunteer for the play?”

Henry sighed. That, it turned out, was easy, and he had a theory as to why:

Everyone wanted to be the president, because the president was the boss.

Everyone wanted to be the servant, because like them, the servant dreamed of murdering the boss.

Everyone wanted to be the son, because it was the son who got to do the killing. And it was this character, Alejo, whose name was changed. He became Espejo.

And indeed, the project sold itself. A week of talking to his peers, and then the delicate process of auditions. Henry had to write in extra parts to avoid disappointing some of the would-be actors. It was for his own safety—some of these men didn’t take rejection very well. He added a chorus of citizens, to comment on the action. Ghosts of servants past to stalk across the stage in a fury, wearing costumes fashioned from old bed sheets. He even wrote a few lines for the president’s wife, Nora, played with verve by Carmen, the block’s most fashionable transvestite. Things were going well. Someone from Diciembre alerted the press (how had this happened? Neither Henry nor Patalarga could recall), and after he’d done an interview or two, there was no turning back. Espejo even joined the enthusiasm. It would be good for their image, he was heard to say.

Rogelio wanted to audition too, but there was a problem.

“I can’t read,” he confessed to Henry. He was ashamed. “How can I learn the script?”

At this point in our interview, Henry fell silent once more. He scratched the left side of his head with his right hand, such that his arm reached across his face, hiding his eyes. It was a deliberate and evasive gesture; I was reminded of children who close their eyes when they don’t want anyone to see them. We sat in Henry’s apartment, where he’d lived since separating from Ana’s mother more than four years before. There was a couch, two plastic lawn chairs that looked out of place indoors, and a simple wooden table. One might have thought he’d just moved in.

“Rogelio was my best friend, you know?”

“I know,” I said.

“At a time when I needed a friend more than I ever had before. I loved him.”

“I know.”

“And even so—before we went on tour again, just now, I hadn’t thought about him in years. I find this a little shameful, you know? Do you see how awful it is?”

I nodded for him to go on, but he didn’t. “It’s not your fault,” I said. “You didn’t destroy the prison. You didn’t send the soldiers in.”

“You’re right,” Henry said.

“You taught him to read.”

“But I didn’t save him.”

“You couldn’t have.”

“Precisely.”

We decided to break. It was time. I excused myself, wandered back to the bathroom at the end of the hallway and splashed cold water on my face. When I returned, Henry was standing on the narrow balcony of his apartment, wearing the same look of exhaustion, of worry. In the tiny park in front of his building, some children were drawing on the sidewalk.

“My daughter draws much better,” he said.

When we went back inside, I asked him what he’d expected from the tour, what his hopes were. He began to speak, then stopped, pausing to think. “If the text of a play constructs a world,” Henry said finally, “then a tour is a journey into that world. That’s what we were preparing for. That’s what I wanted. To enter the world of the play, and escape my life. I wanted to leave the city and enter a universe where we were all someone different.” He sighed. “I forbade Nelson to call home.”

“Why?”

“I wanted him to help me build this illusion. I needed his help. This sounds grandiose, and dramatic, I know, but …”

I told him not to worry about how it sounded. “Did you have any misgivings about it?”

It was a poorly phrased question. What he’d been trying to tell me was this: his misgivings in those days were all encompassing, generalized, profound. He could push them away for hours at a time, but with only great effort. And they returned. Always.

“To be quite honest, it wasn’t the tour I was afraid of,” Henry said. “It was everything.”

AT MY REQUEST, Ana’s mother took a look at the notebook, spending a few moments with the pages, smiling occasionally as her eye alighted on a particular phrase or observation. She read a couple lines aloud, letting out a short, bitter laugh now and then. When she was finished, she shook her head.

“He gave you these?” Henry’s ex-wife asked, wide-eyed.

I told her he had.

“Henry’s the moody type,” she said, “nothing new. An artist. Always was. But he could enter these spirals of unpleasantness, just like what you describe. Only he wouldn’t write it down, not like this. In eight years—was it that long? Jesus—in eight years, I never saw him write down anything that wasn’t for the classes at that school where he taught. Teaches. Whatever. But he’d talk this way sometimes, stream of consciousness, chatter. At night mostly. Imagine living with this!”

She threw two hands in the air, and the notebook tumbled to the floor.

“I can’t believe I’m going to tell you this,” she said, “but listen. Toward the end, he was never home, God bless. He’d go to school, and then drive the cab till ten. He’d come home, climb into bed, and say: Baby, I fucked a passenger today, on the way to the airport. Wonderful, I’d say, half-asleep, but you still have to fuck me. I’m your wife. It was a game, see? And at first he would. Four times a week. Then three. Then once. But then, he wouldn’t—sleep with me, I mean. Not at all. He’d sleep beside me, but I’d be awake, waiting. He’d snore, and I’d want to kill him. I’d put my hand on his cock. Nothing. Like touching a corpse. He would talk in his sleep, nonsense like this stuff here.” She picked up the fallen notebook, shaking the pages at me. “And then one day, I realized that it wasn’t just stories, it was true: he actually was fucking his passengers. I said, Henry, I’m leaving. Do you know how he responded? Did he tell you this?”

I shook my head.

“He said, ‘Oh, no, the turtle’s getting away! Hurry!’ I thought he was drunk. On drugs. I slapped him. Do you hate me? I asked. I was hurt, you understand. Angry. Do you hate me, I said. Is that it? Do you hate our life? Are you trying to break my heart?”

“How did he respond?”

“He collapsed, sobbing, and told me no. That he hated himself, that he had for years.” She laughed drily. “That his unhappiness was a monument! Like a statue in the Old City. One of those nameless heroes covered in bird shit, riding a stone horse. I told him not to try his poetry now. That it was too late. He begged me to stay.”

“But you didn’t.”

“Of course not. I left him, like any reasonable, self-respecting woman would’ve done. He’d slept with half the city, but it wasn’t his fault because he was depressed? If I’d stayed a moment longer, I would’ve put a steak knife through his neck. Or through my own. So I took Ana, and we went to my mother’s house.”

“Did you ever meet Nelson?”

As it turns out she had, during the last week of rehearsals before they left the city. One afternoon she dropped their daughter off at the Olympic. (“What a dump, and how sad to see it that way! I don’t know why Patalarga would’ve wasted a cent on that place.”) She got to see some of the play. It was the last week of rehearsals.

What did she think?

“About the play, or about Nelson?”

“Both.”

She frowned. Nelson admired Henry without reservation—that much was clear to her. She saw about half a rehearsal, enough to get a sense of the dynamic between them: Henry was hard on Nelson. Interrupted him, chastised him, explained a scene, a beat, once and again; and all the while, Nelson listened carefully to everything, suppressing the frustration he surely must have felt. And he was good. Intense. Very professional. You’d think they were preparing to tour the great halls of Europe, and not a bunch of frostbitten Andean villages.

“And the play?”

Ana’s mother responded with a question: Did I watch much theater? I told her I did, my fair share.

“You know what? I’d remembered it being funny. Fifteen years ago, Henry had a sense of humor. I didn’t remember it being so fucking dark. It was always there, in the script, I suppose, but he was emphasizing it now. What can I say? Life does that to a man. Patalarga was trying. He’d add a note of slapstick, but it just wasn’t … I mean, it had its moments. I’ll tell you this much, which I’m not sure Henry even knows. My daughter, Ana—she fell asleep. She’s no critic, but there it is. She slept. Soundly.”

When our interview was over, Henry’s ex-wife excused herself for having spoken so crudely. “I don’t hate him, I just wouldn’t say Henry brought out the best in me. We’re better off apart.” She paused. “Or at least I am, which really is what matters. To me, I mean.”

I told her that I appreciated her honesty.

She asked that her name not be printed. It’s been years, but I’m honoring that request.