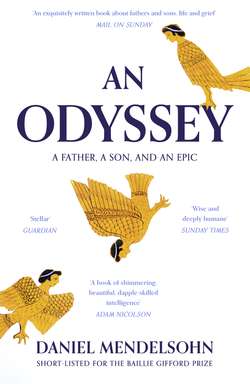

Читать книгу An Odyssey: A Father, A Son and an Epic: SHORTLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZE 2017 - Daniel Mendelsohn, Daniel Mendelsohn - Страница 8

ОглавлениеOne January evening a few years ago, just before the beginning of the spring term in which I was going to be teaching an undergraduate seminar on the Odyssey, my father, a retired research scientist who was then aged eighty-one, asked me, for reasons I thought I understood at the time, if he might sit in on the course, and I said yes. Once a week for the next sixteen weeks he would make the trip between the house in the Long Island suburbs where I grew up, a modest split-level in which he still lived with my mother, to the riverside campus of the small college where I teach, which is called Bard. At ten past ten each Friday morning, he would take a seat among the freshmen who were enrolled in the course, seventeen- or eighteen-year-olds not even a quarter his age, and join in the discussion of this old poem, an epic about long journeys and long marriages and what it means to yearn for home.

It was deep winter when that term began, and when my father wasn’t trying to persuade me that the poem’s hero, Odysseus, wasn’t in fact a “real” hero (because, he would say, he’s a liar and he cheated on his wife!), he was worrying a great deal about the weather: the snow on the windshield, the sleet on the roads, the ice on the walkways. He was afraid of falling, he said, his vowels still marked by his Bronx childhood: fawling. Because of his fear of falling, we would make our way gingerly along the narrow asphalt paths that led to the building where the class met, a brick box as studiedly inoffensive as a Marriott, or up the little walkway to the steep-gabled house at the edge of campus that for a few days each week was my home. To avoid having to make the three-hour trip twice in one day, he would often spend the night in that house, sleeping in the extra bedroom that serves as my study, stretched out on a narrow daybed that had been my childhood bed—a low wooden bed that my father built for me with his own hands when I was old enough to leave my crib. Now there was something about this bed that only my father and I knew: it was made out of a door, a cheap hollow door to which he’d screwed four sturdy wooden legs, securing them with metal brackets that are as solidly attached today as they were fifty years ago when he first joined the steel to the wood. This bed, with its amusing little secret, unknowable unless you hauled off the mattress and saw the paneled door beneath, was the bed on which my father would sleep that spring semester of the Odyssey seminar, not long before he became ill and my brothers and sister and I had to start fathering my father, anxiously watching him as he slept fitfully in a series of enormous, elaborately mechanized contraptions that hardly seemed like beds at all, whirring noisily as they inclined and declined, like cranes. But that came later.

It used to amuse my father that for a long time I divided my time among so many different places: this house on the rural campus; the mellow old home in New Jersey where my boys and their mother lived and where I would spend long weekends; my apartment in New York City, which, as time passed and my life expanded, first to include a family and then to teach, had become little more than a pit stop between train trips. You’re always on the road, my father would sometimes say at the end of a phone conversation, and as he said the word “road” I could picture him shaking his head from side to side in gentle bewilderment. For nearly all of his life my father lived in one house: the one he moved into a month before I was born, and which he left for the last time one January day in 2012, a year to the day after he started my class on the Odyssey.

The Odyssey course ran from late January to early May. A week or so after it ended, I happened to be on the phone with my friend Froma, a Classics scholar who had been my mentor in graduate school and had lately enjoyed hearing my periodic reports about Daddy’s progress over the course of the Odyssey seminar. At some point in the conversation she mentioned a Mediterranean cruise that she’d taken a couple of years before, called “Retracing the Odyssey.” You should do it! Froma exclaimed. After this semester, after teaching the Odyssey to your father, how could you not go? Not everyone agreed: when I e-mailed a travel agent friend of mine, a brisk blond Ukrainian called Yelena, to ask her what she thought, her response came back within a minute: “AVOID THEME CRUISES AT ALL COSTS!” But Froma had been my teacher, and I was still in the habit of obeying her. The next morning, when I called my father and told him about my conversation with her, he made a noncommittal noise and said, Let’s see.

We went online to look at the cruise line’s website. As I slumped on the sofa in my apartment in New York, a little worn out by another week of traveling up and down Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, staring at my laptop, I could picture him sitting in the crowded home office that had once been the bedroom I shared with my older brother, Andrew: the simple low beds that he’d built and the plain oak desk long since replaced by particle-board desks from Staples whose slick black surfaces were already bowed by the weight of the computer equipment on top, the desktops and monitors and laptops and printers and scanners, the looping cables and swags of cords and winking lights giving it all the air of a hospital room. The cruise, we read, would follow the mythic hero’s convoluted, decade-long itinerary as he made his way home from the Trojan War, plagued by shipwrecks and monsters. It would begin at Troy, the site of which is located in what is now Turkey, and end on Itháki, a small island in the western Greek sea that purports to be Ithaca, the place Odysseus called home. “Retracing the Odyssey” was an “educational” cruise, and although he was contemptuous of anything that struck him as a needless luxury—cruises and sightseeing and vacations—my father was a great believer in education. And so a few weeks later, in June, fresh from our recent immersion in the text of the Homeric epic, we took the cruise, which lasted ten days in all, one day for each year of Odysseus’ long journey home.

During our voyage we saw nearly everything we’d hoped to see, the strange new landscapes and the debris of the various civilizations that had occupied them. We saw Troy, which to our untrained eye looked like nothing so much as a sand castle that’s been kicked in by a malicious child, its legendary heights reduced by now to a random agglomeration of columns and huge stones blindly facing the sea below. We saw the Neolithic monoliths on the island of Gozo, off Malta, where there is also a cave that is said to have been the home of Calypso, the beautiful nymph on whose island Odysseus was stranded for seven years during his travels, and who offered him immortality if only he would forsake his wife for her, but he refused. We saw the elegantly severe columns of a Doric temple left unfinished, for reasons impossible to know, by some Greeks of the classical era in Segesta, on Sicily—the island where, toward the end of their homeward voyage, Odysseus’ crew ate the forbidden meat of the cattle that belong to the sun god Hyperion, a sin for which they all died. We visited the desolate spot on the Campanian coast near Naples that, the ancients believed, was the entrance to Hades, the Land of the Dead—that being another, unexpected stop on Odysseus’ journey toward home, but perhaps not so unexpected because, after all, we must settle our accounts with the dead before we can get on with our living. We saw fat Venetian forts, squatting on parched Peloponnesian meadows like frogs on a heath after a fire, near Pílos in southern Greece, Homer’s Pylos, a town where, according to the poet, a kindly if somewhat long-winded old king named Nestor is said to have reigned and where he once entertained the young son of Odysseus, who had come there in search of information about his long-lost father: which is how the Odyssey begins, a son gone in search of an absent parent. And of course we saw the sea, too, with its many faces, glass smooth and stone rough, at certain times blithely open and at others tightly inscrutable, sometimes of a weak blue so clear that you could see straight down to the sea urchins at the bottom, as spiked and expectant as mines left over from some war whose causes and combatants no one any longer remembers, and sometimes of an impenetrable purple that is the color of the wine that we refer to as red but the Greeks call black.

We saw all those things during our travels, all those places, and learned a great deal about the peoples who had lived there. My father, in whom a crabbed cautiousness about the dangers of going pretty much anywhere had given rise to certain notorious sayings that his five children loved to mock (the most dangerous place in the world is a parking lot, people drive like maniacs!), came to relish his stint as a Mediterranean tourist. But in the end, as the result of a string of irritating events beyond the control of the captain or his crew, which I will describe presently, we were unable to make the last stop on the itinerary. And so we never saw Ithaca, the place to which Odysseus strove so famously to return; never reached what may be the best-known destination in literature. But then, the Odyssey itself, filled as it is with sudden mishaps and surprising detours, schools its hero in disappointment, and teaches its audience to expect the unexpected. For this reason, our not reaching Ithaca may have been the most Odyssean aspect of our educational cruise.

Expect the unexpected. Late in the autumn that same year, a few months after my father and I returned home from our trip—which, I would sometimes joke with Daddy, because we had never reached our goal, could still be considered to be incomplete, could be thought of as ongoing—my father fell.

There is a term that comes up when you study ancient Greek literature, occurring equally in both imaginative and historical works, used to describe the remote origins of some disaster: arkhê kakôn, “the beginning of the bad things.” Most often the “bad things” in question are wars. The historian Herodotus, for instance, trying to determine the cause of a great war between the Greeks and the Persians that took place in the 480s B.C., says that a decision taken by the Athenians to send ships to some allies many years before the actual opening of hostilities was the arkhê kakôn of that conflict. (Herodotus was writing in the late 400s B.C., approximately three and a half centuries after Homer composed his poems about the Trojan War—which, according to some ancient scholars, had taken place three centuries before Homer lived.) But arkhê kakôn can be used to describe the origins of other kinds of events, too. The tragic playwright Euripides, for instance, uses it in one of his dramas to describe an unhappy marriage, an ill-fated union that set in motion a sequence of events whose disastrous outcome furnishes the climax of his play.

Both war and bad marriages come together in the most famous arkhê kakôn of them all: the moment when a prince of Troy called Paris stole away with a Greek queen called Helen, another man’s wife. So, according to the myth, began the Trojan War, the decade-long conflict waged by the Greeks to win back the wayward Helen and punish the inhabitants of Troy. (One of the reasons the war took so long to prosecute was that Troy was surrounded by impregnable walls; these finally yielded, after a ten-year siege, only because of a trick—the Trojan Horse—devised by the Odyssey’s notoriously crafty hero.) Whatever its basis in remote history may have been—there had indeed been an ancient city located on the Turkish site that my father and I visited, and it was destroyed violently, but beyond that we can only guess—the mythic cataclysm that resulted from Helen’s adultery with Paris has furnished poets and playwrights and novelists with material for the past three and a half millennia: countless deaths on both sides, the shocking sack of the great city, the enslavements and humiliations and infanticides and suicides, and then, finally, the wretchedly prolonged homecomings of those Greeks clever or lucky enough to survive the war itself.

Arkhê kakôn. The second word in that phrase is a form of the Greek kakos, “bad,” which survives in the English “cacophony,” a “bad sound”—a reasonable way to describe the noise made by women as their young children are thrown over the walls of a defeated city, which is one of the bad things that happened after Troy fell. The first word in the phrase, arkhê, which means “beginning”—sometimes it has the sense of “early” or “ancient”—also makes its presence felt in certain English words, for instance “archetype,” which literally means “first model.” An archetype is the earliest instance of a thing, so ancient in its authority that it sets an example for all time. Anything can be an archetype: a weapon, a building, a poem.

For my father, the arkhê kakôn was a minor accident, a single false step that he took in the parking lot of a California supermarket where he and my brother Andrew had gone to get groceries for a long-awaited family reunion. All five of his children were coming with their families to join him and Mother for a long weekend at Andrew and Ginny’s place in the Bay Area; all were traveling great distances to get there. My parenting partner, Lily, and our two boys and I were flying in from New Jersey, my younger brother Matt and his wife and daughter were coming from DC, my youngest brother, Eric, from New York City, our sister, Jennifer, and her husband and small sons from Baltimore. But before any of us got there, my father fell. Like some unlucky character in a myth, he had unwittingly fulfilled his own glum warnings in a way no one could have guessed: for him, a parking lot had turned out to be the most dangerous place of all, but not because of the cars, the people who drive like maniacs. He and Andrew had finished loading the car with groceries, and as Daddy was returning the empty cart he tripped on a metal stanchion and fell. He couldn’t get up, Andrew told me later, he just sat there looking dazed. By the time we all arrived my father was confined to a wheelchair. He’d fractured a bone in his pelvis, an injury from which it would take him months to recover; but of course we knew he would recover, since, as everyone used to say, Jay is tough!

And he was indeed tough, mastering first the wheelchair and then the walker and then the cane. But the fall he’d feared for so long set in motion a series of complications whose outcome was grossly disproportionate to the mishap that had triggered them, the hairline fracture leading to a small blood clot, the blood clot requiring blood thinners, the blood thinners causing, ultimately, a massive stroke that left my father helpless, unrecognizable: unable to breathe on his own, to open his eyes, to move, to speak. At a certain point we were told it would soon be over, but he fought his way back yet again. He was tough, after all, and for a brief period he was well enough to converse about ball games and Mother and a certain Bach piece that he was eager to practice on his electronic keyboard although, he said, he knew it was too hard for him. This last period was one in which (as we would say later on, retelling the remarkable story over and over as if to convince ourselves that it was all real) “his old self” had reappeared: a term that raises questions first posed, as it happens, in the Odyssey, a work whose hero must, at the end of his decades-long absence from home, prove to those who once knew him that he is still “his old self.”

But which is the true self? the Odyssey asks, and how many selves might a man have? As I learned the year my father took my Odyssey course and we retraced the journeys of its hero, the answers can be surprising.

All classical epics begin with what scholars call a proem: the introductory lines that announce to the audience what the epic is about—what will be the scope of its action, the identities of its characters, the nature of its themes. These proems, while formal in tone, perhaps a bit stiffer than the stories that follow, are never very long. Some are almost disingenuously terse, such as the proem of the Iliad, an epic poem of fifteen thousand six hundred and ninety-three lines devoted to a single episode that takes place in the final year of the Trojan War: a bitter quarrel between two Greek warriors—the commander-in-chief, Agamemnon, son of Atreus, and his greatest warrior, Achilles, son of Peleus—that threatened the mission to destroy Troy and avenge the abduction of Helen. (For Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae, the war is personal: Helen’s cuckolded husband, Menelaus, the king of Sparta, is his younger brother. Achilles, for his part, fights only for glory. “The Trojans never did any harm to me,” he bitterly remarks.) In the end, the two warriors reconcile and their mission is successful—although it should be said that the destruction of Troy, the ruse of the Trojan Horse, the nighttime ambush, the slaughter of the city’s warriors and enslavement of its women and children, the razing of its once-impregnable walls, an outcome familiar to the Greek audiences of the epic from their real-life wars and made famous through many literary and artistic representations of the Fall of Troy, is not actually narrated in the course of the Iliad’s fifteen-thousand-some-odd lines. Epics, despite their great length, are in fact tightly focused on whatever theme is announced in their proems. The proem of the Iliad is concerned simply with the quarrel between the two Greek warriors, its causes and effects, and what it reveals about the characters’ understanding of honor and heroism and duty and death. But because epic has a sophisticated array of narrative devices—because it can hint, and foreshadow, and even flash forward into the future—the Iliad leaves us in no doubt as to how things will end.

The proem of the Iliad consists of seven lines:

Rage! Sing the rage, O goddess, of Peleus’ son, Achilles—

devastating rage, which put countless pains upon the Greeks

and hurled to Hades many sturdy souls of

heroes, while making their bodies into pickings for dogs

and all manner of birds, as Zeus’ plan was achieving its fulfillment—

from the moment when first the two stood forth in strife,

Atreus’ son, the lord of men, and Achilles, a man like a god.

In themselves, these seven lines tell us fairly little about the plot of the epic. We know simply that there is rage, death, and a divine plan; Agamemnon and Achilles. The reference to Zeus’ plan is arrestingly coy: what exactly is it? How are the rage and the pain and the dogs and birds helping to fulfill it? We aren’t told right away, and there’s no doubt that part of the reason the poet hints without explaining is to make us keep listening—to make us find out what this plan is. But it’s also hard not to feel that the reference to a “plan” is slyly pointed: for it implies that the poet, at least, has a plan, even though at this early point we have only the dimmest idea of what it might be. In epic, we need the proem because it reassures us, at the very moment we set out upon what might look like a vast ocean of words, that this expanse is not a “formless void” (like the one with which another great story, Genesis, begins) but a route, a path that will take us someplace worth going.

“Someplace worth going” is a good way to summarize the great preoccupation of the Odyssey, which in certain ways is a sequel to the Iliad. A poem of twelve thousand one hundred and ten lines, it takes as its subject the convoluted and adventure-filled return home of one of the Greeks who took part in the war against Troy. This particular Greek is Odysseus, the ruler of a small island kingdom called Ithaca; he is a trickster about whose ruses and ploys, some successful, others not, the Greeks loved to tell tales. One of the most popular of these legends concerns the run-up to the Trojan War. We are told that when the Greeks came asking Odysseus to join their coalition in the war against Troy, Odysseus—“a clever man,” as an ancient commentator on the Odyssey drily observed, “who perceived how vast the conflict would be”—tried to avoid conscription by pretending to be crazy: in the presence of the Greek scout he yoked an ass and an ox together and began to plow salt into his fields. Familiar with his reputation, the scout took Telemachus, Odysseus’ infant son, and placed the baby on the soil in front of the plow; when Odysseus swerved to avoid his child, the scout concluded that he couldn’t be all that crazy, and took him away to the war.

The conflict was indeed vast—but so are Odysseus’ trials during his protracted homeward voyage. For he is continually harassed and delayed, shipwrecked and castaway, by the machinations of the angry sea god, Poseidon, whom Odysseus has offended (for reasons we learn later in the poem) and whom the hero will learn to appease only after he finally gets home. Odysseus’ far-flung wanderings over ten years as he struggles to return to his wife, Penelope, and their son—to get back to his family and home—stand in stark contrast to the immobility of the Greeks as they sat before the walls of Troy during the ten years of their war. So, too, does the mutual devotion of the couple at the heart of the Odyssey—Odysseus, whose allegiance to the wife he hasn’t seen in twenty years withstands the seductive attentions of various goddesses and nymphs whom he encounters on his way home, and Penelope, who remains true to him in the face of the aggressive attentions of the Suitors, the dozens of young men who have taken up residence in her palace, intent on marrying her—stand in sharply ironic contrast to the adulterous affair between Paris and Helen that was the cause of the war in the first place: the arkhê kakôn.

Most classicists agree that the proem of the Odyssey consists of its first ten lines:

A man—track his tale for me, Muse, the twisty one who

wandered widely, once he’d sacked Troy’s holy citadel;

he saw the cities of many men and knew their minds,

and suffered deeply in his soul upon the sea

try as he might to protect his life and the day of his men’s return;

but he could not save his men, although he longed to;

for they perished through their wanton recklessness,

fools who ate of the cattle of Hyperion,

the Sun; and so they lost the day of their return.

From some point or another, Daughter of Zeus, tell us the tale.

It is an odd way to begin. After modestly introducing his subject as, simply, “a man”—Odysseus’ name isn’t mentioned—the poet seems to wander away from this “man” to other men: that is, the men whom he had commanded and who, this proem tells us, died through their own recklessness. Just as the man himself had widely wandered, so does the proem.

Perhaps inevitably, in the case of this meandering work about a meandering and unexpectedly prolonged homecoming, some scholars have argued that the proem of the Odyssey itself strays: that, in fact, it runs for the first twenty-one lines of the poem. The eleven additional lines describe the circumstances in which Odysseus’ divine patroness, Athena, the goddess of wisdom, urges her father, Zeus, king of the gods, to bring Odysseus home at last despite the implacable opposition of the enraged sea god:

… tell us the tale.

Now all the others—those who’d fled steep death—

were home at last, safe from war and sea;

but he alone, yearning for home and wife,

was detained—by the Lady Calypso, most heavenly of goddesses,

in her hollow caves: she longed to marry him.

But then the time came in the course of the whirling years

when the gods devised a way to bring him home

to Ithaca; but even there he was hardly free of woe,

even when he was back among his people. All the gods felt pity

for him except Poseidon, who raged hotly against

Odysseus, that godlike man, until he reached his homeland.

And so, again very much like Odysseus, the proem not only wanders, but may wander on longer than it had intended to.

The Iliad and the Odyssey are the most famous epics in the Western tradition, but they are far from being the only ones to come down to us from Greek and Roman days. The landscape of classical Greek and Roman literature, from the two Homeric poems in the eighth century B.C. to Christian verse epics composed in the fifth century A.D., was dotted with epic poems, which reared up from those landscapes much the way that Troy must have risen from its smooth plain above the sea, seemingly unassailable and permanent. Even when the poems themselves were lost over the millennia, as many of them were, the proems often survived, precisely because of their gripping succinctness.

A proem could memorialize other poems. Take, for example, the proem of Virgil’s Aeneid, which knowingly alludes to the opening lines of both the Iliad and Odyssey:

Wars and a man I sing: the first who came

from Troy to Italy and to Latium’s shores,

exiled by Fate: tossed about on land and sea

by the violence of the gods above, all because

of the ever-wakeful wrath of savage Juno;

he suffered greatly too in war, so he could found

his city and bring his gods to Latium, whence arose

the Latin people, the Alban fathers, and the walls of lofty Rome.

The Aeneid revisits the world of Homer’s poems but radically shifts their point of view to that of the losers: it retails the adventures of Aeneas, one of the few Trojans to survive the Greek obliteration of Troy. After escaping the burning wreckage of his city with (this is one of the epic’s most famous and touching details) his father strapped to his back and his young son in tow, Aeneas first undergoes a series of elaborate wanderings (meanderings that remind us of the Odyssey) before he settles in Italy, the land that has been promised to him as the homeland of the new state that he will found, where he must then fight a series of grim battles against the locals (warfare that reminds us of the Iliad) in order to establish himself and his people forever. While he lacks the cruel glamour of the Iliad’s Achilles or the seductive slyness of Odysseus, Aeneas does embody a dogged sense of filial obligation, a quality much prized in Roman culture and signaled by the Latin adjective most often used of Virgil’s hero: pius, which means not “pious,” as might seem natural to an English-speaker’s eye, but “dutiful.” The proem of the Aeneid is seven lines long; the first of these, in which the poet announces that he will sing of “wars and a man,” arma virumque, is itself a nod to both the Iliad, which is above all about “wars” or “arms,” arma, and to the Odyssey, whose own first line, as we know, announces that it is about “a man.”

A proem, therefore, can not only summarize its own action, look into its own future, and forecast, in miniature, what is to come, but can nod gratefully backward in time at the earlier epics, the archetypes, to which it is indebted.

When I was growing up, there was a story my father liked to tell about a long journey he and I once made, a story that hinged on a riddle. How, my father would inevitably ask at some point as he told this story, not quite looking you in the eye while he talked—a habit my mother disliked and about which she would sometimes scold him because, she would say, it makes you look like a liar, a reproof that amused us children because one thing that everyone knew about my father was that he never lied—How, my father would ask when he told this story, can you travel great distances without getting anywhere? Because I was a character in this story, I knew the answer, and because I was only a child when my father started telling this story, I naturally enjoyed spoiling his telling of it by giving the answer away before he reached the end of his tale. But my father was a patient man, and although he could be severe, he rarely scolded me.

The answer to the riddle was this: If you travel in circles. My father, who was trained as a mathematician, knew all about circles, and I suppose that if I had cared to ask him he would have shared with me what he knew about them; but because I have always been made nervous by arithmetic and geometries and quadratics, unforgiving systems that allow for no shadings or embellishments, no evasions or lies, I had an aversion even then to math. Anyway, his esteem for circles was not the reason he liked to tell this story. The reason he liked to tell it was that it showed what kind of boy I had once been; although now that I am grown up and have children of my own, I think that it is a story about him.

A long journey he and I once made. In the interests of precision, a quality my father much admired, I should say that the trip we made together was a homecoming. The story starts with a son who goes to rescue his father, but, as sometimes happens when travel is involved, the journey home ended up eclipsing the drama that had set it in motion.

The son in question was my father. It was the mid-1960s, and so he would have been in his mid-thirties; his father, in his mid-seventies. I must have been four or so; at any rate, I know that I wasn’t yet old enough to go to school, because that’s why I was the one chosen to accompany my father. It was January: Andrew, four years older than I, was in the second grade, and Matt, two years younger, was still in diapers, and my mother stayed home with them. Why don’t I take Daniel, Marlene? I remember my father saying, a remark that made an impression because until then I don’t think I’d ever done anything alone with him. Andrew was the one who went places with Daddy and did things with him, handed him tools as he lay on the concrete floor of the garage under the big black Chevy, stood next to him in front of the workbench in the basement as they pored over model airplane instructions. I thought of myself, then, as wholly my mother’s child. But Andrew was in school, and so I went with Daddy down to Florida when my grandmother called and said, Come quickly.

In those days my father’s parents lived on the ninth floor of a high-rise apartment building in Miami Beach overlooking the water—a building, as it happened, that was located next door to the one in which my mother’s father and his wife lived. I doubt that the two couples spent a lot of time with each other. My mother’s father, Grandpa, was garrulous and funny, a great storyteller and wheedler; vain and domineering, he devoted a good deal of thought each day to the selection of the clothes that he was going to wear and to the state of his gastrointestinal tract. Although he had only one child, my mother, he’d had four wives—and, as my father once hissed at me, a mistress. The average length of these marriages was eleven years.

My father’s father, by contrast—Poppy, the object of our traveling that January when I was four—barely spoke at all. Unlike my mother’s father, Poppy wasn’t given to displays of, or demands for, affection. A small man—at five foot three he was dwarfed by my tall grandmother, Nanny Kay—he always seemed vaguely surprised, on those occasions when we drove to Kennedy Airport to pick up the two of them, when you gave him a welcoming hug. He liked being alone and didn’t approve of loud noises. He’d been a union electrician. You’ll hurt the wiring! he would cry out in his high, slightly hollow voice when we ran around the living room; we would tiptoe for the next fifteen minutes, giggling. He took his modest enjoyments, listening to comedy shows on the radio or fishing in silence off the pier in back of his building, with quiet care—as if he thought that, by being cautious even in his pleasures, he might not draw the attention of the tragic Fury that, we knew, had devastated his youth: the poverty so dire that his father had had to put his seven brothers and sisters in an orphanage, his mother and all those siblings and his first wife, too, all dead by the time he was a young man. These losses were so catastrophic that they’d left him “shell-shocked”—the word I once overheard Nanny Kay whisper as she gossiped with my mother and aunts under a willow tree one summer afternoon when I was fourteen or so and was eavesdropping nearby. He was shell-shocked, Nanny had said as she exhaled the smoke from one of her long cigarettes, explaining to her daughters-in-law why her husband was so quiet, why he didn’t like to talk much to his wife, to his sons, to his grandchildren; a habit of silence that, as I knew well, could be passed from generation to generation, like DNA.

For my father, too, liked peace and quiet, liked to find a spot where he could read or watch the ball game without interruption. And no wonder. I’d heard from my mother about how tiny his family’s apartment in the Bronx had been, and I’d always imagined that his yearning for peace and quiet was a reaction to that cramped existence: sharing a foldout bed in the living room with his older brother Bobby, who’d been crippled by polio (I remember the sound as he leaned his iron leg braces against the radiator before we got into bed, he told me years later, shaking his head), his parents just yards away in the one small bedroom, Poppy listening to Jack Benny on the radio, Nanny smoking and playing solitaire. How had they managed before his oldest brother, Howard, went off and joined the army in 1938? I couldn’t imagine … And yet since he himself had gone on to have five children, I had to believe that my father also, paradoxically, craved activity and noise and life in his own house. Why else, I sometimes asked myself, would he have had so many kids? Once, when I was talking about all this with Lily—the boys were small, Peter maybe five or six, Thomas, never a good sleeper, tossing restlessly in his crib, muttering little cries as he slept, not yet two—I asked this question about my father out loud. Lily looked at me and said, Well, you grew up in a crowded house with lots of siblings, and you wanted to have kids, didn’t you? And it was a lot more complicated for you! I grinned, thinking of how it had all begun and how far we’d come: her shy request, when she’d first started thinking of having a child, whether I might want to be some kind of father figure to the baby; how nervous I’d been at first and yet how mesmerized, too, once Peter was born, how increasingly reluctant I’d grown to return to Manhattan after a few days visiting with them in New Jersey; the gradual easing, over months and then years, into a new schedule, half a week in Manhattan, half in New Jersey; and then Thomas’ arrival somehow cementing it all. Your first kid, it feels like a miracle, almost like a surprise, my father had said when I told him about Thomas. After that, it’s your life. All that had been five years earlier; now, as I wondered aloud why my father had had so many children, Lily cocked her head to one side. I thought she was listening for Thomas, but she was thinking. It’s funny, she said slowly, that you ended up doing just what your father did.

For this reason—because the men in that family didn’t talk much to others, didn’t share their feelings and dramas the way my mother’s relatives did—it seemed strange to me that one day we had to rush down to Florida to be with Poppy, my small, silent grandfather. Only gradually did I perceive the reasons for Nanny’s frantic phone call: he was gravely ill. So we went to the airport and got on a plane and then spent a week or so in Florida in the hospital room, waiting, I supposed, for him to die. The hospital bed was screened by a curtain with a pattern of pink and green fish, and the thought that Poppy had to be hidden filled me with terror. I dared not look beyond it. Instead, I sat on an orange plastic chair and I read, or played with my toys. I have no memory of what my father did during all those days at the hospital. Even when his father was well, I knew, they didn’t talk much; the point, I somehow understood, was that Daddy was there, that he had come. Your father is your father, he told me a decade later when Poppy was really dying, this time in a hospital near our house on Long Island. Many of my father’s pronouncements took this x is x form, always with the implication that to think otherwise, to admit that x could be anything other than x, was to abandon the strict codes that governed his thinking and held the world in place: Excellence is excellence, period; or Smart is smart, there’s no such thing as being a “bad test taker.” Your father is your father. Every day during Poppy’s quiet final decline in the summer of 1975, my father would drive to this hospital on his lunch break, a drive of fifteen minutes or so, and sit eating a sandwich in silence next to the high bed on which his father lay, seeming to grow smaller each day, as desiccated and immobile as a mummy, oblivious, dreaming perhaps of his dead wife and many dead siblings. Your father is your father, Daddy replied when I was fifteen and asked him why, if his father didn’t even know he was there, he kept coming to the hospital. But that would come later. Now, in Miami Beach in 1964, he was sitting in the tiny space behind the curtain with the fish, talking quietly with his mother and waiting. And then the tiny old man who was my father’s father, who had had a heart attack, did not die; and the drama was over.

It was when we flew home that the strange return, the circling, began.

Who wandered widely.

The English language has several nouns for the act of moving through geographical space from one point to another. The provenances of these words, the places they came from, can be interesting; can tell us something about what we have thought, over the centuries and millennia, about just what this act consists of and what it means.

“Voyage,” for instance, derives from the Old French voiage, a word that comes into English (as so many do) from Latin, in this case the word viaticum, “provisions for a journey.” Lurking within viaticum itself is the feminine noun via, “road.” So you might say that “voyage” is saturated in the material: what you bring along when you move through space (“provisions for a journey”), and indeed what you tread upon as you do so: the road.

“Journey,” on the other hand—another word for the same activity—is rooted in the temporal, derived as it is from the Old French jornée, a word that traces its ancestry to the Latin diurnum, “the portion for a day,” which stems ultimately from dies, “day.” It is not hard to imagine how “the portion for the day” became the word for “trip”: long ago, when a journey might take months and even years—say, from Troy, now a crumbling ruin in Turkey, to Ithaca, a rocky island in the Ionian Sea, a place undistinguished by any significant remains—long ago it was safer and more comfortable to speak not of the “voyage,” the viaticum, what you needed to survive your movement through space, but of a single day’s progress. Over time, the part came to stand for the whole, one day’s movement for however long it takes to get where you’re going—which could be a week, a month, a year, even (as we know) ten years. What is touching about the word “journey” is the thought that in those olden days, when the word was newborn, just one day’s worth of movement was a significant enough activity, an arduous enough enterprise, to warrant a name of its own: journey.

This talk of arduousness brings me to a third way of referring to the activity we are considering here: “travel.” Today, when we hear the word, we think of pleasure, something you do in your spare time, the name of a section of the paper that you linger over on a Sunday. What is the connection to arduousness? “Travel,” as it happens, is a first cousin of “travail,” which the chunky Merriam-Webster dictionary that my father bought for me almost forty years ago, when I was on the eve of the first significant journey I myself ever made—from our New York suburb to the University of Virginia, North to South, high school to college—defines as “painful or laborious effort.” Pain can indeed be glimpsed, like a palimpsest, dimly floating behind the letters that spell TRAVAIL, thanks to the word’s odd etymology: it comes to us, via Middle English and after a restful stop in Old French, from the medieval Latin trepalium, “instrument of torture.” So “travel” suggests the emotional dimension of traveling: not its material accessories, or how long it may last, but how it feels. For in the days when these words took their shape and meaning, travel was above all difficult, painful, arduous, something strenuously avoided by most people.

The one word in the English language that combines all of the various resonances that belong severally to “voyage” and “journey” and “travel”—the distance but also the time, the time but also the emotion, the arduousness and the danger—comes not from Latin but from Greek. That word is “odyssey.”

We owe this word to two proper nouns. Most recently, it derives from the classical Greek odysseia: the name of an epic poem about a hero called Odysseus. Now many people know that Odysseus’ story is about voyages: he traveled far by sea, after all, and (ironically) lost not only everything that he started out with but everything he accumulated on the way. (So much for “provisions for a journey.”) People also know that he traveled through time, too: the decade he and the Greeks were besieging Troy, the ten arduous years he spent trying to return home, where sensible people stay put.

So we know about the voyages and the journey, the space and the time. What very few people know, unless they know Greek, is that the magical third element—emotion—is built into the name of this curious hero. A story that is told within the Odyssey describes the day on which the infant Odysseus got his name; the story, to which I shall return, conveniently provides the etymology for that name. Just as you can see the Latin word via lurking in viaticum (and, thus, in voiage and “voyage” as well), people who know Greek can see, just below the surface of the name “Odysseus,” the word odynê. You may think you don’t recognize it, but think again. Think, for instance, of the word “anodyne,” which the dictionary my father gave me defines as “a painkilling drug or medicine; not likely to provoke offense.” “Anodyne” is actually a compound of two Greek words which together mean “without pain”; the an- is the “without,” and so the -odynê has to be “pain.” This is the root of Odysseus’ name, and of his poem’s name, too. The hero of this vast epic of voyaging, journeying, and travel is, literally, “the man of pain.” He is the one who travels; he is the one who suffers.

And how not? For a tale of travel is, necessarily, also a tale of separation, of being sundered from the ones you are leaving behind. Even people who have not read the Odyssey are likely to have heard the legend of a man who spent ten years trying to get home to his wife; and yet, as you learn in the epic’s opening scenes, when Odysseus left home for Troy he also abandoned an infant son and a thriving father. The structure of the poem underscores the importance of these two characters: it begins with the now-grown son setting out in search of his lost parent (four whole books, as its chapters are called, are dedicated to the son’s journeys before we even meet his father); and it ends not with the triumphant reunion of the hero and his wife, but with a tearstained reunion between him and his father, by now an old and broken man.

As much as it is a tale of husbands and wives, then, this story is just as much—perhaps even more—about fathers and sons.

And knew the minds of many men.

From Miami we flew home to New York. It was night. As we settled into our seats, the stewardess mentioned that there was “bad weather” waiting at home. Daddy briefly looked up from the book that he was reading, registered the information, and then went back to the book. Soon after we were in the air, however, the pilot announced that, because of the weather, there would be a lengthy delay before we could land; we would have to “circle.” The plane started to bank gently, and for a long time we went round and round. Up where we were, there was no weather at all: the night was as dense and matte as the piece of velvet a jeweler might use to display his stones—like the jeweler from whom, my mother once whispered to me, her own father had bought her engagement ring, haggling in a narrow back room on Forty-Seventh Street with an old Jewish man, one of Grandpa’s many, many friends, who rolled some uncut brilliants onto the black cloth as he and my grandfather argued in Yiddish, all because my father didn’t have enough money to buy the kind of stone her father thought she should have—the sky was like a piece of black velvet and the stars were like those brilliant winking stones. I knew that we were going in circles because the moon, as round and smoothly luminescent as an opal, kept disappearing and then reappearing in my window. I had a book of my own that night but ignored it when the circling first began, happily looking at the moon instead as it went past once, twice, three, four times, I eventually stopped counting how many times it showed its bland face to me.

My father wasn’t looking at the moon. He was reading.

But then he always seemed to be reading. My father, whose parents never got beyond high school, once told me a story about how he became a great reader. Having been misdiagnosed with rheumatic fever in the seventh grade, he’d had to stay in bed for months, and during that period he became attached to books. There’s nothing you can’t do if you have the right book, he liked to tell his five children, and he, at least, lived by his own rule. He was never happier than when puzzling over his latest haul from the public library, some volume about how to play jazz guitar, how to play drums and recorder, violin and piano, how to write pop lyrics, how to construct a built-in wet bar, how to build an accelerator for the barbecue coals, how to make a compost heap, Colonial furniture, a harpsichord. At the end of Book 5 of the Odyssey, when the love-mad nymph Calypso finally allows Odysseus to leave her island and make his way toward home, she fetches a set of tools that she had hitherto kept locked away and gives them to the shipwrecked man; it is with these few tools, and whatever trees and plants there are to hand, that the hero builds himself the raft on which he begins the final legs of his journey home. Whenever I read this passage, I think of my father.

In part because he seemed always to be coiled over a book, always to be using his own mind and absorbing the contents of others’, when I was a child I thought of my father as being all head. The impression that his head was the greater part of him was enhanced by the fact that he went bald when he was still quite young, certainly by the time I was a small child, and the impression I had was that the massive brain beneath his skull had expanded to the point where it had, somehow, forced the hair from his scalp. Many of my memories of him start with an image not of his face—the sallow oval with its arced brows and narrowly set dark brown eyes, the long broken nose with the rubbery swerve at the end, the thin-lipped mouth that tended to be set in a tight frown—but of his head, which, devoid of hair, seemed almost touchingly exposed, available to injury. A fringe of residual hair made a U around the base of his head, this U being dark throughout my childhood, gray later on, then shaved, and then, bizarrely, a little fuzzy again because of the drugs he had to take. And then there was the forehead, nearly always wrinkled in concentration as he thought his way through a problem, an equation, my mother, one of us.

This was the head that was bent, that night of the long and circling plane ride, over a book.

What was my father reading? It isn’t impossible that it was a Latin grammar, or maybe Virgil’s Aeneid, the Roman epic that nods so elegantly to its Greek archetypes. Although my father spent his working life among scientists and equations and figures—first in his job at Grumman, an aerospace corporation, where whatever he did was unknown and unknowable to us, since the facility he worked in was top secret, and besides, as he later pointed out to me, I wouldn’t understand; and then, after he retired in the 1990s, during a second, decade-long career teaching computer science at a local university—he took pride in the fact that he had once, long ago, been a Latin student. Oh, he would say sometimes, when I was in college and majoring in Classics, Oh, in high school I read Ovid in Latin, you know! And I, instead of being impressed, as he hoped I would be, by this early feat of scholarship, noticed only that he’d pronounced the poet’s name with a long o: Oh-vid. My father’s mispronunciations, which embarrassed me a great deal at one point in my life, were the inevitable result of him having been the bookish child of parents who had no education to speak of; I suspect a good many of the proper names and words he had encountered, by the time I was old enough to disdain his errors, were words he’d never heard uttered aloud. Only now do I see how greatly to his credit it was that he himself would be the first to joke about these gaffes. I was in the army before I realized there was no such thing as “battle fa-ti-gyoo”! he’d say with a tight little grin, and if I happened to be there when he was telling this joke on himself I would wait, with a complicated pleasure, for the person he was telling it to to realize that the word in question was “fatigue.”

So my father liked to boast that he had been good enough in Latin to read Oh-vid in the original, although I came, in time, to know that a great regret of his was that he had stopped studying Latin before he had a chance to read Virgil. The knowledge that my father had never finished Latin, had never read the Aeneid, gave me a faintly cruel satisfaction, since I myself pursued and eventually completed my classical studies and had, therefore, read Virgil in Latin; and Virgil’s Latin, as I would sometimes take pleasure in pointing out to my father, was denser, more complicated, and more difficult than was Ovid’s.

Throughout the years I was growing up, my father would occasionally make a stab at recouping what he had lost all those years ago, back in the late 1940s. I would sometimes come home to Long Island on spring or fall break to find his copies of Latina pro populo (“Latin for People”) and Winnie ille Pu lying next to the black leather recliner downstairs in the den where he would try, and often fail, to find the solitude he craved. Already when I was a child of seven or eight or nine, I was reading books about the Greeks and their mythologies, drawn, no doubt, by the allure of naked bodies and of lascivious acts, by the heroes and the armor and the gods, the ruined temples and lost treasures, and although I never suspected it at the time, I now realize that my father liked the idea that I had an antiquarian bent.

Years later—long after I had failed, in high school, to master the math courses that would have allowed me to go on to study calculus—my father would occasionally remark that it was too bad, because it’s impossible to see the world clearly if you don’t know calculus. He said this not to hurt me but from, I believe, genuine regret. It was too bad, he would say; just as, at other times, he would say that it was too bad that I couldn’t appreciate the “aesthetic dimension” of math, a phrase that made no sense to me whatsoever because I associated mathematics with being forced to perform fruitless exercises that had no purpose, and only much later did I realize that they only seemed to have no purpose because I wasn’t working hard enough, or maybe wasn’t being taught well enough (Why isn’t your teacher explaining these things better? he would exclaim, shaking his shiny head in dismay, although when I asked him to explain the same things he would shake his head again, confounded by my inability to grasp what was so clear to him), and so I went on cluelessly through junior high school and high school, uncomprehendingly copying out diagrams and geometric shapes and quadratic equations, having no idea what they were supposed to be leading to, like someone forced to practice scales on a guitar or piano or harpsichord without guessing that there was something called a concerto. Much later, when I was a freshman in college learning Greek, I sat in a classroom with three other students every weekday morning at nine o’clock, and we would recite, precisely the way you might play scales, the paradigms of nouns and verbs, each noun with its five possible incarnations depending on its function in the sentence, each verb with its scarily metastasizing forms, the tenses and moods that don’t exist in English, the active and passive voices, yes, those I knew about from high-school French, but also the strange “middle” voice, a mode in which the subject is also the object, a strange folding over or doubling, the way a person could be a father but also a son. And yet I happily endured these rigorous exercises because I had a clear idea of where they were leading me. I was going to read Greek, the Iliad and the Odyssey, the elaborately unspooling Histories of Herodotus, the tragedies constructed as beautifully as clocks, as implacably as traps … Years after all this, whenever my father made this comment about how you couldn’t see the world clearly without calculus, I’d invariably reply by saying that you couldn’t really see the world clearly without having read the Aeneid in Latin, either. And then he’d make that little grimace that we all knew, half a smile, half a frown, twisting his face, and we’d laugh a sour little laugh, and retreat to our corners.

So he might have been studying his Latin, perhaps even taking a stab at Virgil, that night when we circled for hours in the airplane bringing us back from Florida, where my dutiful father had hurried to be with his silent parent. Years later, when he said he wanted to take my course on the Odyssey, it occurred to me that you might devote yourself to a text out of a sense of guilt, a sense that you have unfinished business, the way you might have a feeling of obligation to a person. My father was a man who felt his responsibilities deeply, which I suppose is why, when I asked him a certain question years later, he replied, simply, Because a man doesn’t leave.

That night when I was four years old I sat there, quiet next to my quiet father, as the plane leaned heavily on one wing so that it could spin its vast arcing circle, not unlike the way in which, in Homer’s epics, a giant eagle will wheel high in the sky above the heads of an anxious army or a solitary man at a moment of great danger, the eagle being an omen of what is to come, victory or defeat for the army, rescue or death for the man; I sat as the plane went round and my father read. I don’t remember how long we circled, but my father later insisted that it was “for hours.” Now if this were a story told by my mother’s father, I’d be inclined to doubt this. But my father loathed exaggeration, as indeed he disliked excess of all kinds, and so I imagine that we did, in fact, circle for hours. Two? Three? I’ll never know. Eventually I fell asleep. We stopped circling and began our descent and landed and then drove the thirty minutes or so through the cold and were safely home.

When my father told this story, he abbreviated what, to me, was the interesting part—the heart attack, the (as I saw it) poignant rush to my grandfather’s side, the drama—and lingered on what, to me at the time, had been the boring part: the circling. He liked to tell this story because, to his mind, it showed what a good child I had been: how uncomplainingly I had borne the tedium of all that circling, all that distance without progress. He never made a fuss, my father, who disliked fusses, would say, and even then, young as I was, I dimly understood that the gentle but citrusy emphasis on the word “fuss” was directed, somehow, at my mother and her family. He never made a fuss, Daddy would say with an approving nod. He just sat there, reading, not saying a word.

Long voyages, no fuss. Many years have passed since our long and circuitous return home, and during those years I myself have traveled on planes with small children, which is why, when I now think back on my father’s story, two things strike me. The first is that it is really a story about how good my father was. How well he had handled it all, I think now: downplaying the situation, pretending there was nothing unusual, setting an example by sitting quietly himself, and resisting—as I myself would not have done, since in many ways I am, indeed, more my mother’s child, and Grandpa’s grandchild—the impulse to sensationalize or complain.

The second thing I am struck by when I think about this story now is that in all that time we had together on the plane, it never occurred to either one of us to talk to the other.

We were happy to have our books.

Twists and turns.

It is not for nothing that, in the original Greek, the first word in the first line of the twelve thousand one hundred and ten that make up the Odyssey is andra: “man.” The epic begins with the story of Odysseus’ son, a youth in search of his long-lost father, the hero of this poem; it then focuses on the hero himself, first as he recalls the fabulous adventures he has experienced after leaving Troy, then as he struggles to return home, where he will reclaim his identity as father, husband, and king, taking terrible vengeance on the Suitors who tried to woo his wife and usurp his home and realm; then, in its final book, it gives us a vision of what “a man” might look like once his life’s adventures are over: the hero’s elderly father, the last person with whom Odysseus is reunited, now a decrepit old man alone in his orchard, tired of life. The boy, the man, the ancient: the three ages of man. Which is to say that, among the journeys that this poem charts, there is, too, a man’s journey through life, from birth to death. How do you get there? What is the journey like? And how do you tell the story of it?

The answers are deeply connected with Odysseus’ own nature. The first adjective used to describe the man with whom the proem begins—the first modifier in the entire Odyssey—is a peculiar Greek word, polytropos. The literal meaning of this word is “of many turns”: poly means “many,” and a tropos is a “turning.” English words containing the element -trope are derived, ultimately, from tropos. “Heliotrope,” for instance, is a flower that turns toward the sun. “Apotropaic,” to take a less cheery example, is an adjective that means “turning away evil”: it is used of superstitious rites that are intended to avert bad luck—such as the custom, common among Eastern European Jews of my grandparents’ era, of tying a red ribbon around the wrist of an infant in order to keep the Evil Eye away. Oh, my mother loved you so much, my mother will occasionally say to me, even now, when she took you to the park she would tie a red ribbon around your wrist! And then she’ll cluck her tongue sadly, tskkk, and sigh. The anecdote, I am aware, is not just about my grandmother’s great devotion to me: her deep emotion in this story is meant to stand in contrast to the relative lack of interest in me shown by my father’s parents, who didn’t meet me until I was two years old as the result of one of the grim silences that occasionally arose between my father and his brothers and his parents.

It is difficult to resist the notion that there is something suggestive, programmatic, about making this particular adjective, “of many turns,” the first modifier in the first line of a twelve-thousand-line poem about a journey home. Odysseus, we know, is a tricky character, famed for his shady dealings and evasions and lies and above all his sly way with words; he is, after all, the man who dreamed up the Trojan Horse, a disguise that was also an ambush. So in one sense polytropos is figurative: this is a poem about someone whose mind has many turns, many twists, not all of them strictly legitimate. And yet there is a plainer sense of polytropos. For “of many turns” also refers to the shape of the hero’s motion through space: he is the man who gets where he is going by traveling in circles. In more than one of his adventures, he leaves a place only to return to it, sometimes inadvertently. And then of course there is the biggest circle of all, the one that brings him back to Ithaca, the place he left so long ago that when he finally comes home he and his loved ones are unrecognizable to one another.

The Odyssey narrative itself moves through time in the same convoluted way that Odysseus himself moves through space. The epic begins in a present in which Odysseus’ son, grown to manhood in his father’s absence, goes searching for news of his long-lost parent (Books 1 through 4); it then abandons the son for the father, zooming in on Odysseus at the moment when the gods, having decided that he has wandered enough and should be allowed to go home, free him at long last from the clutches of Calypso and bring him to the island kingdom of a hospitable people called the Phaeacians (Books 5 through 8); then, in a flashback that lasts four full books (9 through 12), Odysseus himself relates to the Phaeacians all of the adventures he has had since leaving Troy. The narrative then comes back to the son in the present, briefly picking up the tale of the youth’s adventures only to turn once more to Odysseus himself as he finally reaches home; then, at last, it brings the father and the son together as they work to reestablish mastery of their home and punish the Suitors and their accomplices (Books 13 through 22). Only after this does the poem reunite the husband and his wife (Book 23) and conclude, finally, with a vision of the men of the family, the son, the father, the grandfather, standing together after vanquishing the Suitors and their families (Book 24): the future and the present and the past juxtaposed in a single climactic moment as the epic draws to its close.

These elaborate circlings in space and time are mirrored in a certain technique found in many works of Greek literature, called ring composition. In ring composition, the narrator will start to tell a story only to pause and loop back to some earlier moment that helps explain an aspect of the story he’s telling—a bit of personal or family history, say—and afterward might even loop back to some earlier moment or object or incident that will help account for that slightly less early moment, thereafter gradually winding his way back to the present, the moment in the narrative that he left in order to provide all this background. Herodotus, for instance, often relies on the technique in his Histories, that sprawling account of the great war between the Greeks and the Persian Empire (a conflict that Herodotus himself saw as a latter-day successor to the Trojan War). At one point, for example, the historian digresses from his military saga to give a book-long history of Egypt, its government, culture, religion, and customs, because Egypt was part of the Persian Empire, whose invasion of Greece in 490 B.C. and the conflicts that ensued from it are the ostensible subjects of the Histories. The vast length of his Egyptian digression suggests that the ancients might have had a very different idea from our own about what it means for a book to be “about” something.

But ring composition undoubtedly arose much earlier than Herodotus and his Histories, clearly before writing was even invented. The most famous example of the technique is, in fact, to be found in the Odyssey: a passage in Book 19, which I shall discuss in greater detail later on, that begins with someone noticing a telltale scar on Odysseus’ leg, at a moment when he is trying to remain incognito. But when the scar is noticed, Homer pauses to tell us how Odysseus, as a youth, got the wound that would become the scar; then goes back even further in time to provide details about an episode in the hero’s infancy (featuring his mother’s father, a notorious trickster); then returns to the incident during which Odysseus got the wound; and finally circles all the way back to the moment when the scar is noticed. Only then, after all the history, does he describe the reaction of the character who noticed it to begin with. As complex as it is to describe this technique, the associative spirals that are its hallmark in fact re-create the way we tell stories in everyday life, looping from one tale to another as we seek to clarify and explain the story with which we started, which is the story to which, eventually, we will return—even if it is sometimes the case that we need to be nudged, to be reminded to get back to our starting point. For this reason, ring composition might remind you of nothing so much as a leisurely homeward journey, interrupted by detours and attractions so alluring that you might forget to stay your homeward course.

And so ring composition, which might at first glance appear to be a digression, reveals itself as an efficient means for a story to embrace the past and the present and sometimes even the future—since some “rings” can loop forward, anticipating events that take place after the conclusion of the main story. In this way a single narrative, even a single moment, can contain a character’s entire biography.

Hence the occurrence of the word polytropos, “of many turns,” “many circled,” in the first line of the Odyssey is a hint as to the nature not only of the poem’s hero but of the poem itself, suggesting as it does that the best way to tell a certain kind of story is to move not straight ahead but in wide and history-laden circles.

In twists and turns.

Fools!

The silence in which my father and I sat all those years ago, on the plane coming home from Miami Beach, was to become typical of what went on between us for a long time. For the first half of my life—until I was in my late twenties—there was a long quiet between us. Perhaps because I had once thought of him as all head, all cranium, the word that came to mind when I thought of him was “hard,” and this hardness made me afraid of him when I was a child and teenager and, indeed, a young man in my twenties. He could be hard on people, certain members of my family would say. He did, indeed, have exacting standards for virtually everything. Grades, certainly, where we children were concerned; but there were other things, too. As I was growing up, I came to understand that everything, for him, was part of a great, almost cosmic struggle between the qualities he would invoke when explaining why a certain piece of music we liked or a movie that was popular at the moment wasn’t really “great,” wasn’t really worth the time we were lavishing on it—those qualities being hardness and durability and, as I think he really meant, authenticity—and the weaker, mushier qualities that most other people settled for, whether in songs or cars or novels or spouses. The lyrics of the pop music we secretly listened to, for instance, were “soft.” A rhyme is a rhyme, you can’t approximate! For him, the more difficult something was to achieve or to appreciate, the more unpleasant to do or to understand, the more likely it was to possess this quality that for him was the hallmark of worthiness.

X is x. His sense that there is a deep and inscrutable essence to things, an irreducible hardness that he had intuited but which many if not most other people had failed to discern, informed his dealings with people, too. Because he had these hard standards—or, rather, because so few people ever met them—there were certain holes in his life, holes that had once been occupied by people: his parents, at one point, during those first two years of my life when he and my mother stopped speaking to his mother and father; each of his three brothers, too, for varying amounts of time, from weeks to years to decades, periods when he would simply not speak to this or that wayward sibling. I was in my thirties before I had a real conversation with Uncle Bobby, with whom some violent quarrel with my father (so we imagined: Daddy never discussed it) had exiled from our lives until the two of them reconciled in the 1990s, when they were in their seventies. And we didn’t even know that he had another older brother, the product of Poppy’s brief first marriage, until my grandfather lay dying and this strange new half-uncle, Milton, showed up in the hospital one day. Milton, Milton, where have you been? Poppy croaked from the high hospital bed as my father looked away in disgust.

So used was I to my father’s habit of silence that it didn’t occur to me until fairly recently to ask why, for him, the obvious way to deal with people who had disappointed his expectations was to act as if they no longer existed.

Hence I was afraid of him for a long time. When I was in grade school and middle school and was having trouble understanding my math homework, I would stand nervously in the doorway to his bedroom, where he would sit at the little teak desk going through bills or reading papers for work, getting up the nerve to ask for his help; once I did, his incredulity in the face of my inability to understand something as obvious to him as the math problem that I couldn’t solve would fill me with shame. This shamed feeling colored my dealings with him through much of the early part of my life, making me want to hide from him. It’s true that I was hiding from many things in those days: I was a gay teenager, it was the 1970s, and we were in the suburbs. I lived cautiously. But the fact is that my anguished, furtive grappling with my sexuality was the least part of my fear of my father back then. I knew well that he and Mother were open-minded and without prejudices on that subject. When I was in high school and a succession of charismatic gay teachers became mentors to me, my parents made efforts to demonstrate that they knew what these men were and had no problem with it. Indeed, my father reacted with surprising gentleness when, as a college junior, I finally came out to my parents. (Let me talk to him, I know something about this, he told my mother, although it would be many years—not until we were on the Odyssey cruise, in fact—before he explained himself.) No: it wasn’t that I was gay. I simply felt that everything about me was hopelessly mushy and imprecise, doomed to fail the x is x test. I didn’t even know what x was—didn’t know what I was or what I wanted, couldn’t account for the turbulent feelings, the heated enthusiasms and clotted fears to which I was prone. And so I hid—from many things, but above all from him, who knew so clearly what was what.

This was the reason, at least on my part, for the long period of quiet between us. What his reasons might be, I never asked.

My resentment of my father’s hardness, of his insistence that difficulty was a hallmark of quality, that pleasure was suspect and toil was worthy, strikes me as ironic now, since I suspect it was those very qualities that attracted me to the study of the Classics in the first place. Even when I was fairly young and first absorbed in books of Greek and Roman myths, I had an idea that beneath the flesh of the lush tales I was reading, with their lascivious couplings and unexpected transformations, there was a hard skeleton that represented some quality fundamental to both the culture that produced the myths and the study of that culture. When I was fourteen, my high-school English teacher instructed us to memorize a passage from a play. Among the austere boxed sets of books on the bookshelves downstairs near the black-upholstered oak rocking chair in which my father liked to read was one called The Complete Greek Tragedies; most of the others were collections of papers about mathematics. I opened one of the volumes in the four-volume set at random and read a speech that turned out to be from Sophocles’ Antigone, a play about a conflict between a headstrong young woman and her uncle, the king, who has issued a harsh new edict that she intends to defy. The speech to which I had randomly turned was one in which Antigone protests that the laws that she obeys are not those made by mortals but the eternal laws of the gods; she declares that she will follow those divine laws even though it means her death. “For me it was not Zeus who made that order, / nor did that Justice who dwells with the gods below / mark out such laws to stand among mankind.” When I read those words, I remember thinking that here at last was the bone beneath the flesh: a play in which x was x, a drama whose action revolves around stark choices between which there was no middle ground. Nothing soft here. When, a few years later, I began to study Greek, I found an equally satisfying flintiness not only in the myths or dramas themselves but in their own bones, the language itself: a syntax that was as stark as Antigone’s choices, that allowed for no messiness or approximation. The paradigms of nouns and adjectives that ran across the pages of the slim black textbook we used in Greek 101 were as crisp and unforgiving as theorems.

Much later I was pleased to learn that my instinct about the “hardness” of Classics itself had been right. The discipline traces its roots back to the late eighteenth century, when a German scholar named Friedrich August Wolf decided that the interpretation of literary texts—an undertaking that many people, among them my father, casually think of as subjective, impressionistic, a matter of opinion—should, in fact, be treated as a rigorous branch of science. For Wolf, many of the theories about education that were circulating at the time were deplorably sentimental and soft—for instance, those being promoted by John Locke in England and Jean-Jacques Rousseau in France, which emphasized the practical aims of education, its role in preparing students for “real life.” What, these philosophers were wondering, could studying the ancient classics possibly teach students in the present day? Locke, like many parents today, derisively wondered why a working person would need to know Latin. Wolf’s answer was, Human nature. For him, the object of his new literary “science”—“philology,” from the Greek for “love of language”—was nothing less than a means to a profound understanding of the “intellectual, sensual, and moral powers of man.” But to study the ancient texts and cultures properly, one had to approach them as scientifically as one did when studying the physical universe. As with mathematics or physics, Wolf argued, meaningful study of classical civilization could arise only from mastery of many essential and interlinked disciplines: immersion not only in Ancient Greek and Latin (and, often, in Hebrew and Sanskrit), in their vocabularies and grammars and syntaxes and prosody, but in the history, religion, philosophy, and art of the cultures that spoke and wrote those languages. To this immersion, he went on, there had to be added the mastery of specialized skills, such as those needed to decipher ancient papyri, manuscripts, and inscriptions, such mastery being as necessary, ultimately, to the study of ancient literature as the mastery of plane and solid geometry, of arithmetic and algebra, and, indeed, of calculus is to proper study of the field we call mathematics.

And so classical philology was born. When I learned about this in graduate school, I shared it with my father. He winced and shook his head and said, Only science is science.

The silence between my father and me started to thaw when I began my graduate study in Classics, when I was twenty-six. Yes, only science was science; but as time went by, it was as if the arduousness of the course of study to which I was devoting myself were eroding his resistance. Whatever he might think of the mushy, subjective business of literary interpretation, he had a grim respect for the classical languages themselves, their grammars as impervious to emotion or subjectivity as any mathematical proof; through mastering them, I had become worthier in his eyes. He started to ask me, with real interest, about the progress of my studies, about what I was reading and how the seminars were conducted. It was at this time, in fact, that he reminisced about his own Latin studies so many years before and shared with me the story of how he’d read Ovid in high school but quit before he’d been able to read Virgil.

During my first year of graduate school I took a seminar on the Aeneid. My father asked me to xerox some pages from Book 2 and send them to him; he wanted to have a go at them, he said. Now as it happens Book 2 is the part of the epic in which the Fall of Troy is recounted in harrowing detail: the awful climax to which the Iliad and Odyssey allude but never fully describe, the one peering into the future toward the devastating event, the other gazing backward at it. It is Virgil, the Roman, who gives us the whole story at last: the Greeks hidden within the gigantic Trojan Horse, which the Trojans have taken inside their city’s walls; then the ambush in the dark, the smoke from the burning city, the panic and the flames; the image of the headless trunk of the murdered Trojan king, Priam, a pitiable old man, the quintessential epic father, who is slain before the altar at which he desperately prays for the safety of his city by Neoptolemus, the son of the now-dead Achilles—a youth who, by killing the elderly king, seeks to outdo his own father in cruel bravery. My father wanted to see some pages from Book 2 because, he said, he was curious to know whether he’d be able to follow the Latin. But too much time had passed since those days decades earlier when he had read Oh-vid so fluently.

It’s no good, he told me over the phone one night, with that tight rueful tone he could sometimes have, a tone of voice that was the vocal equivalent of someone frowning and waving a hand dismissively, as if to say, Why bother?

It’s no use. I’m just no good at this anymore, he said after he’d had a go at Priam and Neoptolemus. It’s too late.

Oh, well, I said. It was so long ago. Nobody could remember all that.

To which my father replied, It’s okay. Now you’ll read it for me.