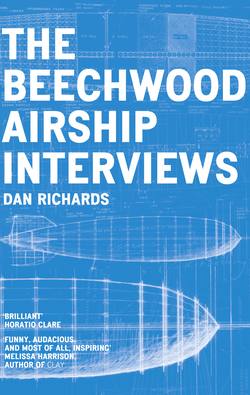

Читать книгу The Beechwood Airship Interviews - Dan Richards - Страница 9

ОглавлениеRICHARD LAWRENCE (1958– ) is a British letterpress printer based in Oxford.

He started printing at school in 1970 and bought his first press (a Heidelberg platen) in 1976. As well as commercial printing work, he teaches letterpress and linocut courses at the St Bride Foundation in London.

RICHARD LAWRENCE

Widcombe Studios, Bath

2008–2011

Returned home to Bristol from Norfolk, I found myself in a post-MA slump. Unsure of what to do next, I began working on a house renovation, returning life to a wreck, digging retrospective foundations where the Georgians hadn’t seen fit – claggy mud, army boots, two pairs of trousers, early dark starts, insipid rain … it wasn’t much like art school. ‘Well, at least I’m still working with my hands,’ I’d think, dubiously.

After a couple of months, around Christmas 2008, my father told me he’d met an interesting Bath-based letterpress printer who worked with a lot of old kit. I’d written nothing since talking to Bill (I’m not sure I’d even listened back to the tapes). Something about coming home had stumped me and I wasn’t sure where my idea for the book was headed. So I’d stopped. But something about the idea of talking to a printer brought thoughts of the brilliant time had in a Thames boat yard back to mind. I’d known very little about boat building but the craftsmanship and enthusiasm I’d discovered in Henley had inspired and re-energised the whole airship project – my MA too, perhaps – so I telephoned the printer, Richard Lawrence, and asked if I could talk to him about his work. He wasn’t keen, explaining it would likely be very disappointing and tedious for me since what he did was in no way arty, but we arranged to meet in any case after I’d explained that few things could be as disappointing as digging footings with a spade in the freezing cold.

Stood beside the River Avon, Richard’s workshop was a single-storey building with a pitched roof made of corrugated iron but held together with moss.

Mist from the river hung level with the gutters.

I remember the hefty padlock on the garage door was green and its long-term knocking had worn away a hollow in the wood behind it.

The first thing I saw once inside was a print of Fleet Street being consumed by fire and flood – one of a series of linocut visions by Stanley Donwood, an artist with whom Richard had worked for several years; the inky nous to the Donwood dash.*

At the time of my visit they’d recently finished work on a project called Six Inch Records and remnants of the printed sleeves and card inners were piled up on the printshop’s central bench.

Once sat with coffee, Richard explained the division of labour:

‘I do this because I love the machinery and am fascinated by the process of squashing ink onto paper. It’s nice if what you end up producing looks nice but that’s not actually why I do it. (Laughs) I mean, obviously it’s a lot more satisfying to produce something that looks good; and it really doesn’t take any more effort to produce something that looks good than something that looks bad.

Against which it’s very interesting dealing with Stanley. (He points up to a drying rack of prints) Those posters are very obviously made up of broken old wood type. If I had my printer’s hat on I’d go through and replace all the letters that are wonky and fiddle until it all printed solid and so on but that’s not what he wants, he wants it to look like that. That’s why it’s printed on brown paper. (Laughs) It’s rubbish!’

You’re the technician and Stanley’s the artist, then, but where’s the tipping point do you think? What is the difference?

‘In my case, the difference is that I do not have the artistic skill to produce an image that looks nice. So the tipping point between art and straight printing is probably the ability to produce a printing surface that is considered a piece of art. Recently I’ve fallen back on this theory: “I am someone who knows how to put ink on paper” … but it’s very interesting, this distinction between craft and art.

Printing is a design skill, a practical application of common sense.’

Editorial common sense.

‘Exactly. It’s a very difficult dividing line and there’s an enormous amount of expediency in what I do which I don’t think people appreciate. That’s something that Stanley is very good about, actually – he’ll have a vague idea of what he wants but then quite happily bend it or, you might say, be inspired by what’s available. That’s the essence of all the typography that I do. I have an idea of what it would be nice to do and then I think, “Well, what have I actually got with which I could do it?”

‘Somewhere along the way I spent some time at Reading University doing a History of Printing, Design & Typography degree and one of the things that people there say – and it’s very much the way I feel, working with letterpress – is that letterpress is extremely good training for typography and design simply because of the number of things that you can’t easily do. You’re constrained in all sorts of ways and you’re made to work with what there is. It’s a very interesting exercise.

‘A few years ago I had the order of service to do for a funeral and there was a lot of copy in it, a lot of words, and I found I’d only enough of one typeface to typeset the whole thing. You’re then confronted with the problem of how to distinguish all the instructional headings for the congregation, delineate between hymns and pieces of text and, armed with one size of one typeface in roman and italic you can actually produce something that is extremely … I mean, “functional” makes it sound boring but you can produce something that works extremely well and looks good, having started with one option.

If I’d been doing it on a computer it would have been very easy to have as many sizes of type as I wanted and as many fonts but it would have been less thought out – that’s the other constraint with letterpress, if you’re typesetting a lot of material, doing it by hand, it takes a long time and you can’t, at the end of it, say, “Oh, I think it would look better if it was a half a point bigger,” and click a button. It doesn’t work like that. You have to decide before you start what you are doing. It inspires you to plan.’

• • • • •

There are three presses in the printshop proper. An Albion hand-press stands in a corner with an air of solid menace. Next to this a black and chrome press runs the length of the workshop wall – shrouded by a greenish tarp. ORIGINAL HEIDELBERG CYLINDER. 1958. Wheels, handles, dials and levers poke out at intervals, like Dalek punctuation.

To the right sits HEIDELBERG 1965, a smaller machine which Richard now starts and lets run. As the paper in the feed is fed up to the hinged ink jaw – the myriad movements are crisp and hypnotic – I realise the noise is taking me back to my childhood and the top-left-hand corner of Wales.

‘Pish ti’coo; Pish ti’coo; Pish ti’coo; Pish ti’coo …’

Ivor the Engine reincarnated as a press* and, indeed, all the presses here are substantial, locomotive-like apparatuses – sat still and quiet now but potentially very loud and powerful. Richard resembles a lion tamer sat in their midst.

‘The thing that puts a lot of people off owning one of these is the sheer size – it weighs almost exactly a ton.

Like all letterpress machines, you need an inky surface and a piece of paper and you squash one against the other. That’s it. That’s printing.

This press achieves that by running ink rollers over the surface, and the really clever bit of this machine is the feed mechanism which, rather ingeniously, can suck just one piece of paper up, deliver it to the gripper-arms which then rotate, carrying the paper.’

He hands me a newly printed sheet, the slight indentations of the pressed type just visible if I hold it up at an angle to the light.

‘Most of the trick to running this is knowing how to make it pick up one sheet and not two and not none. What you get good at, after a while, is looking at the pile and listening to the noises the press makes so that, if it does do something wrong, you can very quickly figure out why. You can adjust the number of suckers turned on, you can adjust both the height and strength of the blow that comes through the pile, you can adjust the angle of attack of the suckers, you can adjust how fast the pile is driven upwards and, depending on the thickness of the paper, what height it’s picked from. By adjusting one or all of those things, you can get it to pick up one sheet of anything you want – from very thin paper right up to beer-mat board. Have you ever made balsa wood aeroplanes? They’re done on these, that’s how you print and cut out the pieces for the kits – die cutting. (Rummages through a box file on a shelf by the sink) That’s a cutting die and that’s what it does.’

Richard puts a rectangular piece of wood on the bench. A maze of metal blades project up from it, surrounded by small, close-fitting blocks of foam.

‘The important bit is the shaped cutting rule – it’s quite sharp. If you imagine pushing the die into a piece of card, it would tend to stick in it, so the foam is there to push it apart again.’

Are fold-lines made in the same way but with blunt rules?

‘Yes, the folding rules are rounded on top and very slightly lower than the ones which cut. These are made in Bristol. If you ask people, “What’s printed the most?” the bulk would say newspapers or books when, in fact, it’s packaging material. Cereal packets win hands-down. The vast majority of printing around the world is for packaging and along with packaging comes boxes and for those you need die cutting.’*

Rooting through another box, Richard pulls out a block comprising two interlocking parts. A piece of paper or card placed between these matched male and female dies* will emerge embossed – the design pressed through the page. This is blind embossing, he explains, ‘blind’ because it is an inkless process, the pressure of the press moulding the material into a relief – the definition wrought by the light.

The examples of the practice that he proffers have a wonderfully tactile quality. Fingertips trace the contours of a set of Stanley’s bears – stamped into a furrowed map for a Six Inch Record outer, a linear Braille-scape.

I hadn’t considered printing presses being put to work ‘dry’ in this way. The technique seems so elegant. I ask how Richard cleans his type and presses down.

‘White spirit. You can use paraffin but it leaves a slightly oily residue behind.

One thing I run into which irritates the hell out of me is that the whole letterpress printing thing has been taken over by “creative” people, artists and such, some of whom have, what I consider to be, absurd ideas about safety. There are aspects of this which are clearly very unsafe – don’t stick your head in a moving press; don’t take a handful of lead type and eat it, all that sort of thing – but a lot of people, particularly Americans, are terrified of solvents … and you can get inks that, instead of being based on linseed oil, are based on soya oil; you can use cooking oil or soya oil to clean down the machinery afterwards, you can … but it leaves it in the most foul, sticky, gunky condition – if you know what you’re doing, washing a machine up with white spirit, you’ll perhaps use two fluid ounces.’

Can you tell me a bit about your inks?

‘Oh, they’re all boring old linseed oil based inks – you take linseed oil and boil it, then grind pigment into it. I don’t personally do that, there’s an ink making company in South Wales who treat me extremely nicely. I started using them some while ago. I asked them, “Could you possibly, maybe … ?” and they said, “Oh yes, not a problem,” and now they produce six different pots of bespoke colours for about £20 apiece which was about a third of what I’d expected to have to pay. I subsequently looked them up on the internet and they turn out to be Britain’s major ink producers – they’re the people who supply Fleet Street – so what they’re doing piddling around producing pots of obscure colours for me I’ve no idea; but I love them for it.’

Richard crosses over to a shelf, takes a lid off a tin and holds it out. Inside the ink resembles emerald engine grease – sickly, fat and viscous.

‘Here is a tin of green that I bought the other day.’

He up-ends it. Nothing happens.

‘I could probably leave it upside down for an hour before any came out; but some inks are thinner than others. White is a problem.’

He opens a tin of white and lays it sideways on the bench. An ominous bulge begins to form, like angry custard.

‘As you can see, it’s almost able to flow. White is a notoriously difficult colour to work with because white, as a pigment, is lousy and getting enough of it into stuff is very difficult. That’s why, if you ever see white type on black in a magazine it was almost certainly printed black onto white paper rather than the other way round.’

How is white ink made?

‘It’s usually titanium and other stuff – aluminium oxide sometimes, depending upon what you want. Most of the pigments are inorganic chemicals.’

Gone are the days of beetles for blue and suchlike?

‘Um, mostly. (Laughs)

I don’t know what some of the pigments are that they use. Having said that, I bought all these tins of ink for the same price and some had noticeably less in than others because the pigments involved were just that bit more expensive. To this day, a kilogram of blue will cost you more than a kilogram of yellow.’

• • • • •

At this point we pause for more coffee and a Penguin biscuit. Richard sits framed by a stacked tower of drawers that rise floor to skylight, each one partitioned into myriad cells – packed with an unseen type, filed away; dormant words.

Tall, bearded, an L.S. Lowry figure in jumper and gilet, he seems quietly amused by most things – I suppose he’s what people would call diffident, but actually I think it’s another facet of his economy – he’s not one for small talk, reserves judgement. There’s nothing superfluous about him – he’s lean. A spare man.

‘It’s actually quite rare to find someone who is interested. As you’ve probably worked out by now, I’m interested in the technicalities of it. That’s what I get excited about.

The images are great and it’s nice working with people like Stan but it’s the whole business of “How does it work?” that actually excites me.’

Do many people track you down because you work with Stanley?

‘No, thankfully not, somehow it hasn’t happened. He’s very fair about giving me billings on things that I have helped him with but no one seems interested in me, for which I’m eternally grateful. But then, I’ve been to one or two of his launch events and he seems to have a habit of wandering around, not actually telling people who he is.*

Having said fiercely that I’m not an artist, I’m actually a scientist by training. I spent the best part of twenty years working for a publisher in various editorial functions producing maths and science books. I like printing because I can understand how it works – if this bit doesn’t work it’s because that bit isn’t connected to the lever that makes it wiggle … and I can then do something about it. I’m very happy with this lot and if something goes wrong I can fix it.’

Where did you get your presses?

‘Well, the Albion in the corner came from an artist, a genuine artist, who made linocuts and worked at the art school at Banbury. He was getting on to retirement and needed to get rid of it so he advertised in the back of a magazine that I read and I bought it from him.’

Can it be taken apart?

‘It can to a certain extent, yes, but the main casting remains unfeasibly heavy and awkward to move; and while nobody knows what Gutenberg’s press looked like, it was probably very similar – except of course that his was made out of wood rather than metal.

While letterpress continued they were very useful, practical things – they made excellent proof-presses. So, rather than locking something up in a machine forme* and all that – particularly on very large printing machines, terribly tedious – you could ink these by hand and print a sheet or proof very quickly.

‘The 1965 platen came from a printer in Oxford who was closing down. He’d made it to the age of eighty-something and his second replacement knee didn’t really take to it so he decided it was time to retire. I’d got to know him and, when it came time for the machine movers to come and take this away, he suggested that I had a word with them. They were essentially taking it away to recondition it and sell it on – probably for die cutting and blind embossing and that sort of thing. I think I gave them about £400 for it and they took it out of his workshop and dropped it at my house a mile up the road. £400!’

What is it worth now?

‘£400!’ (Laughs)

Really?

(Still laughing) ‘There’s a limited market for them; a limited number of people who know how to use them.

This 1958 Heidelberg came from a private press in Marlborough. I’m very lucky to have got it. They used it very little but kept it in very good condition so it hasn’t done many miles.’

It looks in amazing shape.

‘The longevity of these machines is mind-boggling; if you look in the back of trade magazines you’ll see “Heidelberg, six colour – only 70 million impressions.” If you look after them, oil them and replace the odd bits that do wear out they just go on and on. The one I had before was from 1940-something and it was a little rattly but, if you treated it with a small amount of care it would work absolutely fine. The one I used at school was built in 1920-something – that was definitely on the wrong end of rattly but still worked quite well.’

I imagine Richard using the old school press. I wonder what he was like as a child. He seems to embody a stoic enjoyment; a half-amused smile of concentration on his face. The flat smell of ink on his hands.

‘It’s interesting to see the reaction of people who do come in here. I’ve had quite a few in who used to work in the printing trade and they say, “Ooh, wonderful! The smells of ink!” and so on, and some people get excited by all the curiously shaped lumps of machinery and some get excited about all the bits of woodcut and type and I sort of understand that but what excites me is that “It’s machinery! It works! I can do something with it!”

People get a bit put out, frightened even, when I don’t react in the right way; when I don’t get enthusiastic about the “incredible texture and quality” of something … but I’m a creature from a mechanical world, really. That’s what excites me.’