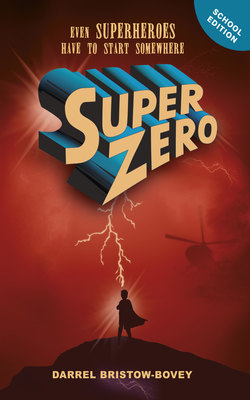

Читать книгу SuperZero (school edition) - Darrel Bristow-Bovey - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBefore reading

| 1. | Who are Clark Kent and Peter Parker? Who are their “alter egos” (super hero identities)? |

| 2. | Has someone made you feel a little nervous and frightened (given you “the creeps”) when you met them? Why? |

| While reading | |

| 3. | What message do the comics have for Zed? |

3. Ulric Chilvers

By the time Zed arrived at school the next day, his head was buzzing with his big idea. What if he’d been a superhero all along, and his father had known about it, and that’s why he’d left the comics for Zed? So that he could read them and learn about his own powers? He couldn’t have left a letter, because what if it was discovered? So he’d left the comics as a kind of code. A secret message.

It would explain so many things – why he felt so different to everyone, and why he was so klutzy. All superheroes are klutzy in their everyday lives, so that no one will ever suspect them. Look at Clark Kent, or Peter Parker. It was all starting to make sense.

He thought about asking his mom about it, but she was too upset about his ripped clothes and his scrapes and cuts. She’d cleaned him up and looked after him and made a fuss, and that had felt too good to spoil with questions about superheroes.

He decided to talk to Katey about it, see what she thought – she was always sensible, but she was also kind, so he knew she wouldn’t just laugh at him – but when he arrived at school he found a great buzz and chatter. Katey ran over to him.

“Zed! Have you heard? There was a fire at Bighton Primary over the weekend …!”

“What …?! Wow!”

“And because so much of the school was burnt down, some of the pupils from Bighton are joining our classes while theirs are being repaired.”

Zed looked around the courtyard and sure enough, among the green Wentville Primary blazers there were patches of kids wearing the bright red blazers of Bighton. Then Zed noticed the boy in a red blazer standing behind Katey, smiling calmly. He was about Zed’s age and he wore his straight black hair much longer than would have been allowed at Wentville. He nodded his head at Zed, and for no reason Zed shivered.

“Oh,” said Katey. “This is Ollrich … we just met.”

“It’s Ulric,” said the boy. “Ulric Chilvers.” He pronounced it “Ooohll-ric”, in a long, slow, drawn-out purr. “I’m pleased to meet you.”

“I’m Zachary,” said Zed. “But my friends call me Zed.”

Ulric Chilvers nodded, staring at him thoughtfully. “Well. Perhaps we’ll be friends,” he said. “You never know.”

He smiled. Zed felt another shiver. Something was wrong – cold electric currents were passing through the air around them. He couldn’t put his finger on it.

“Ulric is a musician,” said Katey. “I was telling him about the school talent show. He’s going to play some music for it, and he wants me to help him with the lyrics.”

“If you wouldn’t mind,” said Ulric Chilvers, bowing his head slightly to her. “I would be terribly grateful.”

It was weird, the way he spoke. He seeemed so confident, so grown-up. Katey looked up at Ulric and giggled. Zed frowned. Katey never giggled.

After school Zed trudged home, deep in thought. He hadn’t had any time to talk to Katey properly – she’d spent most of her free time showing Ulric Chilvers around and talking about his music. Zed was starting to feel a bit stupid about his idea, to tell the truth. How could he ever be a superhero? He wasn’t even as confident and slick and good-looking as someone like Ulric Chilvers. And what super-powers could he possibly have? He tried bending a steel pipe he found beside the road, but he just went red in the face, and the bar didn’t bend.

Zed looked up and realised that he was standing at the gates of Bighton Primary.

He blinked. What made me come here?

The smell of the fire was still in the air. Clearing up had begun and there were large piles of ash and rubble and charred wood.

He wandered across to the courtyard overlooking the upper playing field. What am I doing here? thought Zed. I should go home and try to fix my bike.

But as he turned to go something caught his eye. On the far side of the field were the long-jump pits and past the pits was a line of bushes and behind them a clump of trees. Behind the bushes, in the shade of the trees, were two boys in conversation.

There was something odd – you could see by how they were standing that they didn’t want to be seen or overheard. When people don’t want to be heard, that always makes you want to hear them. Zed tried listening with super-hearing. That was another super-power he didn’t have.

Zed trotted down the stairs and around the outside of the field. He stopped in front of the line of bushes and listened. Silence. Zed looked round, then stepped through the bushes.

The small gap was empty, but the grass had recently been trodden flat by two pairs of feet. There was an empty yellow can of Iced Tea on the ground.

Zed was holding the can and sniffing at it, looking for clues and feeling faintly silly, when there was a rustle of movement.

Zed looked up and his heart briefly ceased beating. Standing behind one of the trees, thick and solid enough to be a tree itself, was a shape in a red blazer. It was a big, scary, ugly shape, with a head like a flowerpot and a face so tough you could use it as a cricket bat. Zed recognised that face, and he recognised that shape. The last time he’d seen it, he’d been in the Wentville goal-mouth, saving a penalty.

It was Daniel Dundee, the captain of the Bighton team, the one whose penalty he’d saved, and who had snarled at him afterwards as though he wanted to tear off his head and use it as a football.

Daniel Dundee glared at Zed, breathing heavily though his mouth.

Maybe he won’t remember me. He must forget things all the time.

“Hey …” said Daniel Dundee, his mind working so slowly you could hear it creaking. “I know you … what are you doing here …?” A look of slow rage grew on his face.

Rats.

Daniel Dundee cracked his knuckles and started shuffling toward Zed, like a gorilla who has found a banana in the jungle.

Zed’s body froze, but his mind was working at super-speed. The bushes at his back were not deep but they were thick and tangly. Daniel Dundee would be on him before he could break clear. Behind Daniel Dundee and the row of trees the ground dropped down sharply, some forty or fifty metres, to the lower field.

Daniel Dundee took another step forward. He was even bigger than Zed remembered, and there was a strange glint in his piggy eyes.

Zed raised his hands, palms open in surrender, but instead of backing away he stepped forward.

“Look,” he said, “I’m really sorry, I think there’s some misunderstanding …”

Suddenly, with a bend of his knees, Zed leapt into the air. He gripped Daniel Dundee’s right shoulder with his own right hand and swung his right elbow forward as hard as he could. Zed was in midair when his forearm smashed into Daniel Dundee’s throat.

The throat is the most vulnerable part of an attacker.

The words echoed in his head. Where had he learnt that? Batman? The Punisher? Luke Cage, Power Man?

Daniel Dundee dropped to his knees, making a wheezing sound.

He vaulted off Daniel Dundee’s stooped shoulders, catching hold of one of the tree branches and swinging forward, twisting in the air to land on the very edge of the drop to the lower field. Below him the grassy bank fell away almost sheer.

Zed caught his breath. The blood sang through his body. Behind him Daniel Dundee lurched heavily to his feet, grunting.

I can do anything! thought Zed wildly. I am a superhero. I can do anything!

Zed didn’t look back, but spread out his arms and lifted his head and launched himself forward, off the grassy bank, out into the air.

I’m flying!

The ground disappeared and his body was suspended in the sky like a gull’s.

I’m flying, he thought again. He opened his mouth to shout it out: “I’m fly …”

That’s when he hit the ground.

Later, when he was washing sand and grass from his mouth, he would think: I learnt two very important things today. One: I can’t fly. Two: If you’re going to land face down in the dirt, you should do it with your mouth closed.

Fortunately, Zed hadn’t dived all the way down – he had simply dived headfirst down the bank and ploughed into it, bounced once and continued downwards, like a riderless surfboard falling down the face of a wave. Then he hit a clump of ferns and tumbled and bounced before fetching up in a heap of arms and legs.

Zed lay there and whimpered. For a few minutes the sky seemed red, then mustard-coloured, and then gradually it returned to blue. Zed whimpered again.

“Come, boy. Don’t cry.”

A pair of hands pulled him upright. He smelt sweat and tobacco and cut grass. Above him Daniel Dundee was silhouetted against the skyline, looming ominously. A figure in blue overalls stepped past him and shook a fist at the silhouette.

“Hayi! Suka! Hamba wena!”

The fearsome outline seemed to hesitate. Its fists clenched, then it turned and disappeared from the lip of the embankment.

Zed sat and slowly gathered himself. It took some time for the sky and the earth to stop spinning. “Thank you,” he said at last.

“I’m Jerome,” said the man. ‘I’m the caretaker here at the school.”

“Ngiyabonga, baba,” said Zed.

Jerome helped him to his feet, throwing another look up the embankment. “That one is no good,” he said, shaking his head.

Zed nodded, testing his limbs to see if anything was missing.

“I saw him,” said Jerome. “That night.”

Zed looked up sharply. “What night?”

“Saturday night,” said Jerome, mopping his brow with his sleeve. “Before the fire.” He nodded in the direction of the caretaker’s rooms. “It was dark, but I saw him. Outside the gates. I knew then there was trouble.”

“Do you think it was him who started the fire?’

Jerome didn’t answer, but his face seemed to darken.

“There has been trouble at this school,” he said. ‘There is something bad at this school. I could feel it. And when the fire came – I wasn’t surprised.”

Zed felt that same shiver pass through him that he’d felt earlier.

Zed left by the bottom gate and walked the long way home. He bundled his grass-stained shirt into the back of the cupboard where his mom might not find it for a while, and brushed his teeth, then brushed them again, but he could still taste grass and sand. His whole body ached. He was too tired even to go to the garage and read more comics.

There was a rattle against his window. Katey was balancing on the fence outside, throwing pebbles. She jumped down and landed neatly in his yard, like Catwoman. She should be the superhero, he thought glumly. She’d be much better than me.

“Hey, Katey,” he said.

“Zed! Why aren’t you dressed?”

“For what?”

“You haven’t forgotten the circus tonight, right?”

The circus!

For weeks they’d been looking forward to Buckman’s New-Worlde Circus. It wasn’t the usual kind of circus, with animals and trapezes and that sort of thing. Richard Finucchio had heard that there were bearded ladies and people who could swallow red-hot coals and Carvella, the world’s fattest woman.

His mom had given permission, and Katey’s folks were going to drop them off and pick them up, and Zed had been as excited about it as anyone. But now he just felt tired and sore, and he wanted to be alone to think about what had happened, and think about the fire at the school, and Daniel Dundee, and he wanted to think about being a superhero …

“Zed! You’re not thinking about flaking out of it, are you? I need someone to go with me!”

“What about Ulric Chilvers?” said Zed. “He’d go with you.”

“I don’t want to go with him,” said Katey. “I want to go with you.”

After reading

| 4. | Why do you think that Katey giggles – something she never does – when she first meets Ulric? |

| 5. | Zed appears to be losing confidence in his own superhero status. Why? Which super-powers does he not have so far? |

| 6. | What history is there between Zed and Daniel Dundee? |

| 7. | What does Zed learn about Bighton School from Jerome, the caretaker? Does this surprise you or not? |

| 8. | What is different about Buckman’s New-Worlde Circus? |

| 9. | What makes Zed say that Katey should go to the circus with Ulric Chilvers instead of him? |

| 10. | Write down an example of onomatopoeia from the first page of this chapter. |

| 11. | What does the expression “he couldn’t put his finger on it” mean? |