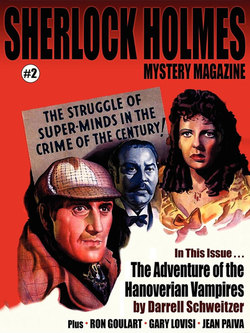

Читать книгу Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine #2 - Darrell Schweitzer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE ADVENTURE OF THE HANOVERIAN VAMPIRES, by Darrell Schweitzer

I found it. It was mine, a pretty, shiny thing, which I found amusing to swat about on the ground for several minutes, watching the evening sunlight gleam off the polished surface. Then, of course, I lost interest and left it where it lay. But it was still mine. So when one of the “street arabs”—verminous boys—snatched it up, I yowled in protest and gave the villain a fine raking on the calf.

He yowled right back and kicked me away. I landed nimbly and hissed, ready for another round of combat.

“What have you got there, Billy?” came another voice.

“I dunno, Mr. ’Olmes.”

“I’ll give you a shilling for it.”

The transaction was done, though the shiny object was still mine.

But now I was content, for the trouser leg I rubbed against belonged to the most perceptive of all human beings, the Great Detective himself, and the result of that encounter is the only Sherlock Holmes adventure ever narrated by a cat.

It is not possible for me to give you my name, for the true names of cats are never revealed outside our secretive tribe, and not even Sherlock Holmes may deduce them; whether the street arabs or Dr. Watson called me Fluffy or Mouser or something far less complimentary is, frankly, beneath notice. Suffice it to say that Holmes and I had a certain understanding by which we recognized and respected one another. You won’t read of any of this in the chronicles penned by the doltish Watson, an altogether inferior lump of clay, who once owned a bulldog pup, probably without appreciating the crucial distinction that one owns a dog but entertains a cat. A dog is a useful object, even as, I suppose, Watson at times was useful.

But he tried to shoo me away, hissing, “Scat!” and other ridiculous imprecations, before Holmes drew his attention to the object in hand.

“It is the clue we have been seeking,” said he. “Come Watson, we have much to do this night. It would be well if you brought your revolver.”

* * * *

Moments later, all three of us were clattering along the rapidly darkening streets of London in a Hansom. At first the driver, like the boorish Watson, objected to my presence, but Holmes gave the driver an extra coin. Watson, dog-like, acquiesced. Holmes would have found it useless to explain to him that cats partake of the most ancient mysteries of the dark, and so have a proper place in any night of intrigue and adventure.

It was indeed such a night.

As we wove through the narrow, filthy streets of the East End, past increasingly disreputable denizens, Holmes held up the shiny thing—which I now conceded I had loaned to Mr. Holmes.

“Deduce, Watson.”

I assume this was a game for Holmes, like swatting a ball of string.

“It is a very thin locket,” said Watson, “for I see that a spring-lock opens it—”

“Look out, Watson!” cried Holmes, for Watson had unthinkingly sprung open the locket, allowing a scrap of paper to flutter out. Deftly, Holmes snatched the paper out of the air.

“What is it, Holmes?”

“Momentarily, Watson. First, the locket.”

“It and its chain are gold-plated.”

“Not silver, Watson. Perhaps you will see the significance of that.”

“Obviously not.” Watson continued. “On one side, is a female portrait—not an attractive one, I dare say—”

“I shall entirely trust your judgment in that department, Watson. Pray, continue.”

“She wears a royal crown. The inscription is in German, and it reads: VICTORIA KAISERIN GROSS BRITANNIEN—Good God, Holmes!”

“Yes, Watson, it is the emblem of the current Hanoverian pretender, whose plottings against our king and country never cease, even after the failure—so ably chronicled by another writer—of the desperate scheme to place St. Paul’s Cathedral on rollers and wheel it into the Thames, back in the days of James the Fourth.”

“God save His Majesty, King James the Sixth, and all the House of Stuart!”

“A sentiment I echo, Watson, but we must hurry on and save the patriotism for our leisure. As you see, we are running out of time.”

I placed my paws on the high dashboard of the Hansom for a better view. We were near the London docks. A fog had settled in among the poorly-lit streets. The air was thick with strange smells. Many of the passers-by were foreigners of the most unsavory sort.

“Recall, Watson,” said Holmes, “that the notorious Dr. Moriarty, before he turned to crime, wrote, in addition to a curious monograph about an asteroid, a treatise on the possibility of an infinity of alternative worlds existing side by side, which may perhaps be realized by the use of certain potent objects—he actually used the word ‘numinous’—which suggest all manner of fantastic combinations, such as, for example, one in which Bonnie Prince Charlie was defeated at Culloden and England today is ruled by this same unhandsome Victoria of the House of Hanover—”

“Good God, Holmes!”

“You could as well imagine a world in which you, Watson, are Grand Panjandrum of Nabobistan, complete with harem. You would enjoy that, would you not?”

“I wouldn’t be with you, Holmes,” he said with some regret.

For an instant I almost admired Watson, though I knew his was mere dog-like loyalty.

“But to conclude,” said Holmes, “it was Moriarty’s theory, which I believe he has passed on to his Hanoverian confederates and which will perhaps be put to the test tonight, that with the use of such an object, which has been manufactured in one of the alternative worlds and conjured into ours, all manner of what the ignorant would call supernatural beings or creatures may be imposed—”

At that moment the Hansom came to a halt. We three debarked. The cab hurried off. I ran ahead of the two humans, into the gloom. The hideous smell of the river and of river rats was ahead of me.

Holmes and Watson hurried to keep pace with me, their great, clumsy feet thundering on the pavement. Dr. Watson gasped between breaths.

“This theory, Holmes, seems perfectly insane—”

“Watson, at such times it pays to be a little mad!”

“And you, the rationalist!”

Holmes made no reply to Watson’s taunt, for we had come to our destination, a deserted wharf amid tumbledown warehouses. The fog was so thick it seemed a solid thing. Even I shivered.

Holmes struck a match for light. He held the paper from inside the locket up so Watson could read it.

“It is a shipping document,” said Watson. “In receipt of five boxes of earth . . . what would anybody want with those, Holmes?”

“Observe the crest, Watson.”

“An odd one. With a bat—”

“It is the arms of a certain voivode of Transylvania, a Count Dracula, about whom many terrible things are whispered. Now all the pieces of the puzzle come together. This Dracula, in the employ of the Hanoverians, under the direction of Moriarty—”

“I don’t understand, Holmes.”

Impatiently, Holmes got out the locket and showed Watson the reverse.

“It’s the same crest, Holmes, to be sure, but—”

I let out a screech of challenge, and at this point Holmes had no time to deal with Watson’s thick-headedness. A low, flat barge drifted out of the fog toward the wharf, heavily laden with long, rectangular boxes.

“Quick, Watson! Under no circumstances must that vessel be allowed to touch land!”

* * * *

The two of them ran to the end of the wharf, and with a long leap all three of us landed squarely in the middle of the approaching barge. Watson’s thick head proved to be of some service at this point, I must admit, because even as we landed one of those disreputable foreigners arose from behind one of the boxes and clubbed Watson with a stout cudgel, which would have broken his skull had it not been so thick, but instead sent him tumbling back against his assailant, who was thus set off balance.

Sherlock Holmes, strikingly agile for a human, had all the advantage he needed. He dealt with the single live crewman on the barge, leaving him unconscious at his feet.

But even he could not quite grasp the true danger. I was the one who first appreciated the significance of the horrible carrion smell which wafted from the boxes, now all the more intense as the lids of those boxes creaked and rose up, opened from within.

In the struggle, Holmes dropped the gold locket. It gleamed even in the poor light.

The thing, which streaked out of one of the boxes far more swiftly than the other occupant could emerge, went straight for the locket, swatted it to one side, then to the other, then turned to confront me.

“Mine!” I communicated, in the secret language of cats, which no human may ever understand.

When I call it a cat, I use the term loosely, for though it had the form of a huge, black-furred tom, it was a dead thing with burning red eyes and glistening fangs. We struggled even as Holmes and his opponents did, both seeking to regain the shiny locket-and-chain, while we rolled right to the edge of the barge’s deck, mere inches above the noxious water.

That was when the inspiration came to me, though I paid a terrible price.

I let go of what was mine. Instantly my enemy grabbed hold of the chain with both forepaws and became entangled, and it took but a single swipe for me to knock him over the side into the water. The carrion-thing let out a hideous yowl, then exploded into steam upon contact with the water and was gone.

As was my pretty treasure.

* * * *

The rest is less interesting. Holmes, seeing a variety of carrion humans emerging from the wooden boxes, heaved first the barge’s anchor, then the semi-conscious Watson and the inert crewman over the side and leapt into the water himself. He stood up, awash to his shoulders. I might have been in a difficult situation had he not allowed me to ride atop his head all the way to shore, while he dragged Watson and the nautical thug.

Once on land, we watched the hideous spectacle of the carrion things stumbling about, seemingly unable to figure any way out of their present predicament.

“The vampires are rendered helpless by the running water of the good Thames,” Holmes explained. “So enfeebled, they cannot even raise the anchor. Daylight will force them back into their boxes, where they are easily destroyed.”

“What I don’t understand,” said Watson, the following morning, back in Baker Street, “is how the locket got there in the first place.”

While they spoke, I lapped a well-deserved saucer of milk, despite Watson’s disapproval.

“I think Count Dracula—who was not among the vampires destroyed, and has yet escaped us—was betrayed by his cat.”

Holmes got out the locket and dangled it by its chain.

Watson stuttered. Even I looked up in amazement.

Holmes laughed. “When the sun rose and the tide went out, I hired one of the Irregulars to splash around in the shallow water until he found it.”

The thought of a “street arab” immersing himself in the nasty element to recover my prize made me think that even boys have their uses.

“Dracula’s feline,” said Holmes, “must have passed from ship to shore many times, perhaps carried by a human agent, to serve as a scout. On one of those missions, it stole the crucial locket, hen, losing interest, abandoned it. The object is a perfect cat-toy, don’t you think?”

He dangled the beautiful thing on its chain. I watched, fascinated. But I continued with my milk. It was mine, after all, and I could play with it later.