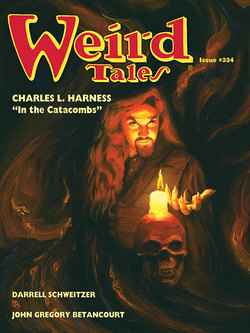

Читать книгу Weird Tales #334 - Darrell Schweitzer - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE DEN, by John Gregory Betancourt

Copyright law is something which affects all readers, but most of them never think about it. From the founding of the United States, Congress has protected authors’ rights. In 1790, copyright lasted 14 years—and could be renewed for 14 more, resulting in a 28-year period of copyright. After that, a work entered the public domain and could be published, edited, abridged, or adapted to other media free of charge. This (so the theory went) resulted in a vital culture, where one author could build upon another’s work.

Over the centuries, copyright laws changed. In 1909, a major copyright reform act expanded the U.S. copyright period to 56 years—an initial 28 years, which could be renewed for another 28 years. (If a work wasn’t renewed, it entered the public domain.) Meanwhile, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works in the Act of Berlin of November 13, 1908 recommended copyright for the author’s life plus 50 years (thus benefitting not just the work’s creator, but several generations of heirs). However, the Copyright Act of 1976 is the one that made the biggest change, adopting the author’s life-plus-50-years rule for works created or published after January 1, 1978. It was extended to life-plus-70-years in 1995 (and from 75 years to 95 years for corporate copyrights), thanks to the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. Why extend copyright so much? Think of the Mickey Mouse company, whose classic cartoons were about to start slipping into the public domain. Hundreds of millions of dollars were at stake, and Sonny Bono acted to benefit the corporate giant (and others like it).

Here is the official argument: “America exports more copyrighted intellectual property than any country in the world, a huge percentage of it to the nations of the European Union. Intellectual property is, in fact, our second largest export: it is an area in which we possess a large trade surplus. At a time when we face trade deficits in many other areas, we cannot afford to abandon 20 years worth of valuable overseas protection now available to our creators and copyright owners. We must adopt a life-plus-70-year term of copyright if we wish to improve our international balance. It just makes plain common sense to ensure fair compensation for the American creators whose efforts fuel this important intellectual property sector of our economy by extending our copyright term to allow American copyright owners to benefit from foreign users. By so doing, we guarantee that our trading partners do not get a free ride for their use of our intellectual property.” (Source: Senator Orrin Hatch, March 2, 1995, Introducing the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1995.)

Personally, I think copyright should be rolled back to the author’s life-plus-20-years. There is no reason to keep work in the public domain any longer than that. At the moment, all works published in 1922 and before are in the public domain in the U.S., which is why so many classics by writers like H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, and the like are remembered today. People can publish them cheaply, or make them available in other media like TV shows, movies, radio, films, etc. without going through a maze of contractual red tape. If these works hadn’t been so omnipresent thanks to the public domain, they might easily be forgotten now. Compare Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes to (say) the Charlie Chan character created by Earl Derr Biggers. Biggers wrote six Charlie Chan books (and more total wordage than Doyle wrote of Holmes). Both had popular film and radio series in the 1930s and 1940s. (There were 14 classic Holmes films with Basil Rathbone, versus 35 classic Chan films with Warner Oland and then Sidney Toler in the title role). Sherlock Holmes, in the public domain, remains popular today.

The Charlie Chan books, still in copyright, are out of print and likely to remain so until 2020. I have been trying to reprint Biggers’s novels through Wildside Press, but after two years of searching, I simply cannot locate the estate. (If anyone knows of it, please—drop me a note!) Biggers worked in the 1930s and his heirs renewed the copyrights to his work in the 1950s, so now, because of all the copyright extensions, the Charlie Chan novels cannot be reprinted until someone comes forward to claim ownership of the them, or until they lapse into the public domain.

It’s a shame.

Look for the copyright period to be extended again around 2019, when Disney’s œuvre is again threatened.

* * * *

This seems to be a special Neil Gaiman review column, albeit unintentionally. Gaiman is emerging as the top fantasist of the early twenty-first century, and he is prolific and varied in his output. Compare his presence in these disparate works:

Shadows Over Baker Street: New Tales of Horror, edited by Michael Reaves and John Pelan

Del Rey, 464 pp., $23.95 (hardcover)

The premise, from the Introduction, is simple: “What if Holmes and Watson were to be confronted by things outside the realm of human experience? What if the inconceivable proved to be true? What if there were places, entities, concepts in the cosmos that man not only did not, but could not understand?” By things they mean the supernatural forces of the Cthulhu Mythos. (Lovecraft’s Mythos is one of the most written-in fictional universes ever created.)

So: Sherlock Holmes. Cthulhu. A high concept collection.

Neil Gaiman leads off a fairly good collection with the short but excellent “A Study in Emerald.” Gaiman knows his Sherlockiana: it’s an early tale of Holmes & Watson, as Holmes uncovers a plot against the crown, investigates a singularly gruesome murder, and visits a play where the return of the Old Ones from R’lyeh and dim Carcosa is enacted as part of history. Gaiman knows his curbs from his kerbs and brings the era properly to life. Interstitial advertisements from the time, which make me think he wrote his story after contributing to The Thackery T. Lamshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, add to the colour. The characters ring true; Holmes is high-handed at times, and Watson is still haunted by his military duty in Afghanistan. Allusions to other works (Doyle’s among them) abound. (You get three bonus points if you pick up on the name Holmes went by while the world assumed he was dead following his trip over the Reichenbach Falls.)

My choice for the best in the book, however, is “The Drowned Geologist,” by Caitlin R. Kiernan. It’s among the least faithful to the Mythos theme, drawing more from Dracula than the Cthulhu Mythos. There are also solid contributions from both editors, Brian Stableford, and Richard A. Lupoff. The “Most Fun” award goes to F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre’s “The Adventure of Exham Priory,” in which Professor Moriarty plans a one-way trip to Yith for Holmes. (MacIntyre is just as well read as Gaiman, I think; he works in some Edgar Allan Poe references, ably pastiches some of Lovecraft’s excesses of style, and adds a third version of the “true events” at the Reichenbach Falls.)

The Thackery T. Lamshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, edited by Dr. Jeff VanderMeer and Dr. Mark Roberts

Night Shade Books, 298 pages, $24.00 (hardcover)

With contributions from a dream-team of discredited and would-be physicians (including Drs. Michael Bishop, Neil Gaiman, David Langford, Tim Lebbon, China Miéville, Michael Moorcock, Brian Stableford, Gahan Wilson, and far too many more to count), this is the medical quackery book of the year. Each doctor has glowingly chronicled the history and symptoms of a truly horrible and often horrifying disease. Among my favorites:

Bone Leprosy (or Saint Calamaro’s Leprosy), in which the bones rather than the flesh fall away from the extremities of the body;

Diseasemaker’s Croup, in which medical gibberish overcomes a physician;

Reverse Pinocchio Syndrome, in which the noses of people whose livelihood or happiness depends on lies (such as “priests, politicians, parents of unspeakable ugly babies”) grow inwardly into the skull.

You get the idea. This is a book best read in small gasps. Give one to your family practitioner as a reference.

The Wolves in the Walls, written by Neil Gaiman, illustrated by Dave McKean

HarperCollins, 56 pages, $16.99 (hardcover)

On first glance, this appears to be a children’s picture book. The words and storyline are fairly simple: Lucy keeps hearing sounds in the walls and comes to believe wolves are living there. Nobody believes her. Her mother blames mice. Her brother thinks she’s crazy. Her father says it’s rats—but adds the disturbing “If the wolves come out of the walls, you know it’s all over.”

Of course, the wolves do come out of the walls, but rather than being eaten, the household flees to the garden and the wolves simply take over the house, eating jam and playing video games. How Lucy gets her house back is the real story, with a nice reversal of the wolves’ original appearance.

What age is it appropriate for? My nine-year-old read it and enjoyed it by himself; my six-year-old loved it for a bedtime story. I enjoyed it as a quick preview-read in the bookstore before deciding it wasn’t too gruesome or scary. If you need a present for a child, this is a book you can give with confidence. It doesn’t talk down to them.

The Gashleycrumb Tinies, by Edward Gorey

Harcourt Brace, 64 pages, $9.00 (hardcover)

The Object-Lesson, by Edward Gorey

Harcourt Brace, 32 pages, $12.00 (hardcover)

Two reprints of note are from 1958. The Gashleycrumb Tinies (a macabre A to Z with verses like “E is for Ernest who choked on a peach” and “F is for Fanny sucked dry by a leech”) is definitely not what you’d want to read your children at bedtime…but it is more than worth having on your own bookshelf.

The Object-Lesson (inspired by Samuel Foote’s poem, “The Grand Panjandrum”) is a series of seemingly unrelated cartoons that still seem to flow into each other with a mesmerizing dream-logic. Strange, surreal, puzzling, and addictive; add it to your Gorey shelf, too.