Читать книгу Weird Tales #313 (Summer 1998) - Darrell Schweitzer - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE EYRIE, by the Editors

“That Is Not Dead Which Can Eternal Lie…”

We’re ba…a…ck!

Welcome, just in time for our 75th anniversary, to the pages of Weird Tales, The Unique Magazine, the greatest of all American pulp magazines, once home to H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Ray Bradbury, and even (believe it or not) Tennessee Williams.

To fill you in briefly: Terminus Publishing Company revived Weird Tales in 1988 and published nineteen issues, numbers 290 through 308, up until 1994. Then we lost our license when Hollywood came calling and offered Weird Tales Ltd., the owners of the title, scads of money for use of the title in a television project. Quite sensibly, WT Ltd. took the aforesaid scads. The television project, ultimately, failed to pan out. Now Terminus has been able to lease the title again and resume publication where we left off.

Have we ever been away?

You will notice that this issue is numbered 313 and the last “official” issue was #308, so that implies that the four issues of Worlds of Fantasy & Horror count as Weird Tales. For one thing, we find it enormously convenient to avoid renumbering everyone’s subscriptions. But there’s more to it than that.

When we lost our license back in 1994, we didn’t want to quit. The obvious alternative was to think up another title which fit behind the big red W on the cover and keep on publishing, with continuity, so that the letter column in the first Worlds of Fantasy & Horror referred back to the previous Weird Tales. But for the title on the cover and contents page, it was the same magazine. So, think of Worlds of Fantasy & Horror as Weird Tales-in-exile, a means of keeping the magazine alive until we could get the title back.

What’s in a name? If the name is Spicy Oriental Zeppelin Stories, maybe not very much, but Weird Tales has, for most of this century, commanded respect. We can only promise you that we intend to continue with a magazine worthy of that name.

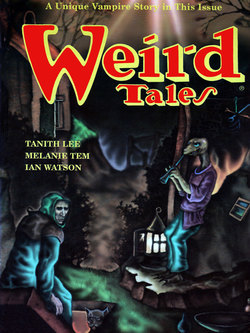

We are pleased to announce that we have also acquired a new publisher, Warren Lapine, of DNA Publications, who is one of the most successful and capable fiction magazine publishers in the business. His science fiction magazine Absolute Magnitude and his vampire-fiction magazine Dreams of Decadence actually make money in a time when most magazine publishers are feeling a sense of doom and gloom, and, particularly, small-press horror magazines seem to be dying like mayflies. We we have joined Warren Lapine’s stable and feel very comfortable there. Our future seems brighter than it has been in a long time. Quarterly publication of Weird Tales will resume, as of this issue. You will continue to see stories by your favorites—and by bright new talents—in future issues. We have some on hand by S.P. Somtow, Tanith Lee, Nicholas DiChario, and quite a few others.

One other change: since George Scithers is no longer officially Publisher, he and Darrell Schweitzer share the position of Co-Editorship, and the “Editorial We” becomes, once again, a genuine plural.

* * * *

Meanwhile, half of the aforesaid “We,” Darrell, found ourselves, flattered, honored, and more than a little surprised by events at the 1997 World Horror Convention in Niagara Falls, New York. We attended in the capacity of Editor Guest of Honor and found the whole thing decidedly eye-opening—

Let’s dispense with the formalities. This is Darrell here. The other guests of honor were writers Joe Lansdale, Poppy Z. Brite, and Ramsey Campbell, and artist Rick Berry. In such company the thought inevitably occurred to me that, after attending (by now) literally hundreds of other conventions in lesser roles, Maybe I Had Arrived.

But arrived at what? Conditions in the horror field have been so dire in the past few years that I was left wondering if there would be anything left to have a World Convention about.

“I have a feeling this may be either a pep rally—or a wake,’’ I said before the affair. It was neither. It was more like a visit to an intensive care ward. Reports of the patient’s demise may be a trifle exaggerated, but Horror is, right now, on the critical list.

Let me say right away that it was a pleasant weekend, everyone was very nice, the Falls are as wet as ever (though the Americans turn them off at night) and the twin towns of Niagara Falls themselves (New York and Ontario) retain that subtle atmosphere of down-at-the-heels tackiness so reminiscent of a somewhat run-down section of the Atlantic City boardwalk plunked down in the middle of the continent.

It might best be summed up in the fun-house maze called Dracula’s Haunted Castle on the Canadian side, which has an impressive exterior; loud, blaring speakers announcing the frightful delights within; and enormous, dripping fangs between which one walks to reach the entrance. But the inside is not quite as good—and scarcely more elaborate—than the “haunted house” you may have put together with your friends at Halloween when you were twelve.

In fact, the one the twelve-year-olds in my neighborhood put together, which scared the crap out of me when I was perhaps six, was considerably more imaginative. There was this girl dressed up as a witch in what might have been an old wedding gown. She glowed from the blue light behind her, and she offered me a jar of what I later realized were olives. “Reach in,” she said in an alluring, spooky voice, “and feel the eyes.” At that point I ran out screaming.

And she didn’t have to rely on a guy popping a paper bag behind your back to deliver the frights, which, I kid you not, the Niagara Falls Dracula castle did.

Delivering the frights is what the game is all about, and the impression I got at World Horror was that no one is delivering much of anything right now. The convention was notably lacking in professional activity, in stark contrast to the bustling World Fantasy Conventions, where authors, agents, editors, and publishers gather by the hundreds to make the deals that determine what you’ll be reading for the next year or so. Representatives of the major New York publishers were conspicuously absent.

I try to convince myself that the Niagara Falls Dracula castle isn’t quite the appropriate metaphor for the state of the horror field right now. And yet…

At the time of the convention, there was no “horror editor” at any publishing house in the United States. There was a time, ten or so years ago, when great quantities of black-covered, gold-embossed paperbacks with demon children or show-through drops of blood poured into the bookstores, when becoming a horror writer was actually a valid strategy for a beginning novelist who wanted to make a living. There was, admittedly, a flood of crud; but lots of good books got published too. The Dell Abyss line promised (and sometimes delivered) great things. The horror field gleamed with prosperity. Writers left fantasy or science fiction, hoping for greener pastures (and bigger paychecks) in the horror field. Editors gathered at conventions to court the writers. The writers gathered to court the editors. The New York publishing world spent lots of money on parties and promotional events.

That’s all gone. At the Niagara Falls convention there was talk that A Certain Publisher Who Shall Remain Nameless was starting a horror line with the worst possible contracts and might get away with it, as the only game in town.

The great Empire has fallen; and the surviving writers, if lucky, will be serfs.

Take a look in the horror section at your local chain bookstore. It’s a lot smaller. Once you take away the brand-name writers who don’t need a category to make their books sell—King, Koontz, McCammon, Brite, Campbell—you’ll discover that the whole section is filled by less than twenty writers, and some of those books are reprints, such as the recent Carroll & Graf edition of William Hope Hodgson’s 1908 classic The House on the Borderland.

And what about magazines? There was a lot of talk about magazines at the World Horror Convention. What particularly threw me for a loop was that I found myself regarded as a hugely-successful, senior figure. What this turned out to mean was that Worlds of Fantasy & Horror (the Once and Future Weird Tales) is one of two bookstore-distributed magazines in the field which has been around for more than a couple of years and has a circulation in four figures. (The other one is Richard Chizmar’s Cemetery Dance.) The editors on the magazine panel with me spoke of 200-copy print-runs. Writers told how wonderful it was to get a whole cent a word for fiction, and how they’d take just copies if need be, to get published. (Weird Tales and Cemetery Dance pay three cents a word and up.)

Now I had never seen ours as a large operation at all. But then I always saw us to be in the broader spectrum of fantastic-fiction magazines, along with The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s Science Fiction, and Interzone. In that company, yes, we are one among many. In the context of what was being accounted as “the horror field” in Niagara Falls, I guess WoF&H must have seemed a titan. Or, to use an architectural metaphor, after all the skyscrapers and castles and gigantic temples have crumbled into dust, two modest little cabins in the back woods—ours and Richard Chizmar’s—are the only things left standing, and therefore the most colossal edifices in the world. Perhaps the “field” is defined too narrowly.

I had another quite interesting conversation in Niagara Falls, with a fellow who ran a “horror” bookstore and boutique in California, one of those places where you can get, in addition to books and magazines, black t-shirts, skull jewelry, etc., etc.

The gentleman’s store moved a lot of books and magazines, he said, particularly anything about vampires. Would he want to carry Worlds of Fantasy & Horror? Well, no. It isn’t “horror.” But our title says “Horror,” and the current issue’s cover has a naked demoness popping out of an eyeball, and we publish Thomas Ligotti, Ramsey Campbell, David Schow, and any number of top horror names.

No, he explained. That’s not “horror.”

Well, by way of a thought experiment, I asked (knowing perfectly well where this was heading): Would his “horror” bookstore carry a book by Clark Ashton Smith, surely one of the most nighmarish writers of all time?

No. Smith has some “dark” elements, I was told, but isn’t horror.

Well how about Edgar Allan Poe? Not “The Masque of the Red Death”? Probably not. I don’t want to tell the bookstore owner his business. He knows better than I what he can and cannot move, but I think this is the heart of the problem: If we define “horror” as scary fiction (with no other emotional tones allowed) which exists only in a modern setting, perhaps only in a Generation-X frame of reference, and if a “horror magazine” is one which publishes such material, to the exclusion of all else, then the field is very small indeed. There is a very intense, very narrow audience for punk/Goth/vampire fiction, but this is—dare we say it?—a passing fad, likely last no longer than the “psychedelic” science fiction of 1967, or a story Henry Kuttner did in the late 1930s about space explorers who landed on the Planet of the Jitterbugs.

An editorial policy of all modern-scene horror—and nothing else—is limiting, especially for a magazine. Of the stories in our last issue, Ian Watson’s “My Vampire Cake” wouldn’t exactly do because it’s funny. The Tanith Lee and Darrell Schweitzer stories are not “horror” because they have imaginary settings. (Which was why the bookstore owner disqualified Clark Ashton Smith. The paradox is this: If the story’s about a Vile, Rotting Thing from beyond the grave, and it’s set in New Jersey in 1997, that’s “horror.” If it’s about a Vile Rotting et cetera and set on the Earth’s last continent in the far future, or in ancient Hyperborea, that is “fantasy.”) The Dunsany and Shipley stories in recent issues don’t quite make it either, leaving, at best, Ligotti’s “Teatro Grottesco” and R. Chetwynd-Hayes’s “The Chair.” So, in the eyes of that California store owner, our magazine isn’t “horror” enough for his clientele, and he may be right.

While we’d like to get our magazine into that California store, at the same time we have to stop and realize that there’s been a severe winnowing out, and we’re just about all that’s left standing. We must be doing something right. This isn’t the time for us to start emulating the losers.

Our magazine continues to be what it’s always been. Weird Tales, throughout its 75-year history, has presented a range of imaginative fiction, from Conan the Barbarian to H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos to the psychic-detective stories of Seabury Quinn. It found room for stories of childhood terrors by Ray Bradbury (most of the ones that make up his classic collection, The October Country,) and H. Rider Haggard-esque (or Indiana Jonesish) Lost Race novels by Edmond Hamilton. We intend the same, with a common denominator, which may be best expressed by a wonderful phrase, used by a correspondent several issues back, to describe the ideal Weird Tales story: “ominous and magical.”

Roll that phrase around in your mind. Balance both halves of it carefully. That’s what the whole field needs. Magic. Imagination. The ability to get out of a completely mundane frame of reference. Fantastic horror.

Too much horror has no imaginative content at all anymore. There’s only room for so many serial-killer books. If writers, booksellers, editors, and even readers start seeing horror only in terms of gore and crazy people with knives, then everyone will tire of it very quickly. By all indications, that’s already happened. The field is wasteland. Dare we suggest that the public is bored with more and more imitations of fewer and fewer books?

Good horror attracts as much as it frightens. It does not repel. It is a careful balance of wonder and terror—as Fritz Leiber so well articulated in various essays, and practiced superbly in his fiction. It does not, Stephen King’s disastrous advice to the contrary, “go for the gross-out,” something which King himself, fortunately, doesn’t do very often.

At the Convention, a small-press publisher was gleefully reading from a new novella which went for the gross-out as much as possible—in fact to a degree seldom seen in legally circulated literature.

Well, fine. This is all very amusing, even as small boys amuse themselves at camp with disgusting stories told in the dark. But that direction seems to me a dead end. It’s a great way to sell about four hundred copies in an expensive, limited edition and no more.

Meanwhile, H.P. Lovecraft sells in the hundreds of thousands of copies, all over the world. I’ve since suggested another topic for a convention discussion: “What Can the Horror Field Learn from Lovecraft?”

What indeed? Lovecraft was around before the rise of “Modern Horror” and he’s still there after its demise. So maybe he knew something too:

Wonder and terror, carefully balanced.

* * * *

Now we (lapsing imperious once again) admit we’re speaking from the position of a winner (or at least a survivor), but none of the foregoing is intended to suggest we’re happy with the state of affairs. We note with guarded optimism that horror books are still being published. As it was a couple decades ago, horror books now have to be slipped into other categories: mystery, science fiction, fantasy, and mainstream.

Bestsellers are bestsellers. King and Koontz still sell. They will continue to sell. Otherwise we suspect that horror fiction is going to have to hide out in the small presses for the next few years, until the buyers for the large bookstores forget just how badly all those horror paperbacks of the boom years sold. Then it will be time to start again, cautiously. We hope there will be more Wonder and less Gross-Out next time around.

More successful magazines will strengthen us all. One hopeful sign is Wetbones, a new magazine started by Paula Guran, who was at that World Fantasy Convention, with an attractive new issue, which, alas, hasn’t had much distribution so far. (Our first impulse was to help. We carried copies back on the plane, to test-market in Philadelphia.) Send her a subscription. See her ad elsewhere in this issue.

We’d like to see other editors and publishers try. If newcomers would like a little advice from such an August and Senior Figures as Ourselves, it is this: Emphasize good writing. Keep the imaginative and fantastic content high. Use covers which suggest, not psychopathology, but fantasy. Design a magazine which would sell on the same shelf with The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, or even Realms of Fantasy, rather than one that looks like a small-press horror magazine of the kind that distributors won’t touch. With a little camouflage, Horror can survive.

* * * *

We Get Letters and not enough of them. However, we were pleased to hear from Timothy Tucker, who comments that the cover on #4 was “sort of a ‘90s update on Margaret Brundage,” to which we suppose we’d agree, save that Douglas Beekman knows human anatomy far better than did the 1930s Weird Tales artist. Mr. Tucker continues:

S.T. Joshi’s essay on child prodigies was very interesting, especially his harsh criticism of Poppy Z. Brite. It would be interesting to hear a response. This is my first exposure to Joshi’s non-Lovecraftian criticism, but he shows himself to be just as astute here as he is in his massive Lovecraft biography.

It is hard to pick out one outstanding story this issue, because all of them were very fine indeed. Right now it appears to be a three-way tie for first among Tanith Lee’s “The Sequence of Swords and Hearts,” Thomas Ligotti’s “Teatro Grottesco,” and your own “The Sorcerer’s Gift.” Both your and Lee’s stories successfully evoke a certain air of ancient myth and folklore. This air is one of the reasons I read fantastic fiction, because it is one of the few places left where such archetypes can be used. In addition, “The Sorcerer’s Gift” is reminiscent of the works of one of my favorite authors, Clark Ashton Smith. I would gladly read more tales of Sekenre the Sorcerer, if you care to write them.

On the other hand, Ligotti’s story is a fine example of updating the first-person-paranoid fiction style used by Poe and Lovecraft. The strange world of the Teatro definitely produces its share of mystery and chills. This issue seems to be a good one for tales in the style of Poe, because “The Chair” by R. Chetwynd-Hayes (is this a pseudonym?) is in the same vein, with a touch of the British ghost story thrown in. A fine effort.

To which we reply variously: No, the author’s real name is R. Chetwynd-Hayes. The initial stands for Ronald. Mr. Chetwynd-Hayes is British, author of many published books, and recipient of a Bram Stoker Award for lifetime achievement.

You’re quite right about the direct use of archetype in fantasy. That is one of its chief appeals, something which any successful writer in this field must understand, and be able to accomplish. As for Sekenre the Sorcerer, he began his career in Weird Tales #303 with “To Become a Sorcerer,” which was expanded into a novel, The Mask of the Sorcerer, published by New English Library in 1995. (Alas, there is no American publisher yet.) The Sekenre story in the present issue is a “reprint” from the British magazine, Interzone, although it has never before been published in North America. Two more stories appeared in Interzone, which might be run in Weird Tales—if there is reader interest. One appears in the final (and 30th) issue of W. Paul Ganley’s Weirdbook, another in the second issue of the new British magazine Odyssey, and yet another is forthcoming in Adventures in Sword & Sorcery. Yes, we would like to write more of them.

Jeffrey Goddin quotes the Irish writer Padraic Collum about Lord Dunsany: “His fantasy is of the highest order. There’s not a social idea in it.” Which could be the basis for a whole new editorial sometime. Ursula Le Guin remarked once that one reads Dunsany for his prose, “since he was a dreadful reactionary,” so maybe it’s just as well.

We might get another editorial out of a clipping from the Philadelphia Inquirer, which reads “Fla. Girl and 4 Other Teens Accused of Killing Her Parents,” with a subtitle, “Police point to a ‘Vampire Clan’ A detective said: ‘They apparently like to suck blood.’” It all sounds much too much lot like the scenario of Christopher Lee Walters’s “The Renfields” in this issue. However, as we’ve had the story in inventory for quite a while, it must be a case art anticipating life.

Lelia Loban Lee writes:

In issue #4, your artist, Douglas Beekman, has outdone himself, with his fine painting of a winning moment in the annual Underworld Eyeball Rolling Competition, a sport too little appreciated on the surface, despite its large and loyal following of fans down below. It’s unfortunate that the competitor’s name does not appear in the credit, but I believe that Beekman depicts the 1988 champion from Eastern Stygia in the Middle-Distance Giant Eyeball Division. For those unfamiliar with Eyeball Rolling, this sport originated as an ancient feast-day ritual to tenderize the fruit of a week-long hunt. While the much smaller goat, human, and monkey eyeballs used in the Pixie Division do not require such treatment for culinary purposes (indeed, the modern style of competition frequently renders eyeballs unfit for consumption), a Cyclopean Giant Eyeball, such as the one shown in the Beekman painting, becomes quite a delicacy when rolled for six to ten miles, pressed, sliced thin, and served raw, with a generous slathering of bat-brain butter. The modern competitor must roll the eyeball (in a manner similar to log-rolling) with feet or equivalent appendages, depending on the athlete’s species, up a steep, rocky incline to a precipice. The athlete must not only balance on the swiftly rolling, wet, slick surface of the orb, but must conserve sufficient energy to break into the interior at the finish, to demonstrate that the eyeball is now palatable. You can see from Beekman’s painting what a rare degree of physical fitness Eyeball Rolling requires. I commend him for introducing this sport to the ignorant and frequently indolent dwellers on the surface.

Just how Ms. Lee came by her first-hand knowledge of this subject, she did not explain.

Franklyn Searight praises a new writer, Jonathan Shipley:

My selection for first place in the Winter 1996–7 issue goes to Jonathan Shipley’s “From the Shores of Tripoli.” I particularly enjoyed his effort because he comes across as an accomplished storyteller, and in my view the story is of the utmost importance. Shipley has not relied upon flowery prose to mask the absence of a decent yarn.

The Most Popular Story in issue #4 was Thomas Ligotti’s ominous and magical “Teatro Grottesco,” with Darrell Schweitzer’s “The Sorcerer’s Gift” a close second, and Jonathan Shipley’s debut story, “From the Shores of Tripoli” a strong third. And the late Margo Skinner’s poem “Prime” also attracted favorable notice.