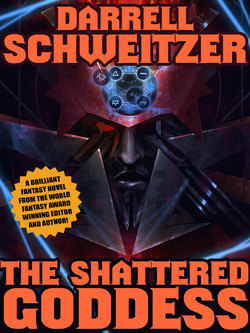

Читать книгу The Shattered Goddess - Darrell Schweitzer - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Like the Child

As the days went by, Kaemen turned out to be a veritable monster, the terror of his nurses, ill-tempered, foul-mouthed at an astonishingly early age, and wholly lacking the grace and moderation of his father. His teeth came in early. He learned how to use them. It nearly cost an old woman a finger.

Like the child, so shall the man be was a proverb of Randelcainé. Despite his name, tie was not the bright hope of anyone.

Ginna was ignored for the most part He was not brought to meals with the high-born children of court, nor did he eat in the kitchen with the servants. Occasionally someone would leave scraps by the door of his room. He was not even taught how to keep himself clean until the stench disturbed Kaemen.

All were forbidden to enter that bare room. Rumor had it a deformed monster was kept there. Once the boy learned to walk, this was to his advantage. He was properly shaped, if undersized, filthy, and pale for want of sunlight. When he wandered about he was often not recognized.

At first the only places he knew were a few musty rooms, a corridor, and the entrance to Kaemen’s nursery, beyond which he was not permitted to pass. He often heard cries and shrieks coming from the nursery, dishes crashing to the floor, and the bare feet of the servants padding back and forth. Those same feet would kick him whenever he tried to investigate, so after a time he learned to keep to himself.

There was a girl who came to play with him, who said she would pretend to be his big sister. She was very big, twice as tall as he. He didn’t know her age, all ages being unimaginable, but she was much wiser than he. She taught him many new words, and how to count on his fingers. He decided he was most happy when she was around, and wished she would be around always.

But then she came no more. Months later he saw her in the hall, straining under a yoke from which two buckets of water hung. A massive woman twice her size walked behind her and glowered. He called her name, but she turned her face away. He never saw her again.

One day a bird came to his window, stood between the bars, and began to sing. It seemed to Ginna that tins song was even more beautiful than any the girl had sung, and more mysterious for not having any words. This was surely the most wondrous creature he had ever encountered.

He stood on a stool and reached for it, but it vanished into the unknown blue void beyond, and then he had a new desire. He wanted to go where it had gone, away from things familiar.

He was three and a half then. He had heard of a world outside but knew nothing about it, and he was aware of his ignorance.

At the end of a certain hallway there was a huge door, too heavy for him to open. It was always kept shut, but sometimes someone was careless. Occasionally he caught glimpses of a stairway on the other side of it, spiraling down into someplace he had never been.

When the young prince bawled that his bathwater was too cold that night, and swore that he would have everyone flayed alive when he was a little older, Ginna saw his chance. There was much scurrying about, and two burly men came through the door with a new tub of steaming water. In their haste they left the door open.

Ginna found the steps too large for his short legs, so he went down backwards like a man on a ladder, dropping from step to step.

He knew he was in a tower from the way he was going down, down, farther than he had ever imagined he would go. The stairs curved away above him until he could no longer see the door. He had truly ventured out of his world.

* * * *

At last the stairway ended. There was a damp stone floor at the bottom, which was cold beneath his feet. A lantern hung from above on a chain, driving the darkness away from a doorway. Over this were two portraits of the same woman, but in each she was different. In one she wore a long black gown sprinkled with stars, and held a serpent in either hand. Lightning flickered above her head. At her feet was a boiling cloud in which hundreds of writhing figures were visible: homed men, serpents, toads with the heads and claws of lions. He had never seen such things. The girl had told him about many animals and described them, but these went well beyond the range of her descriptions. Many were just shapes to him.

The other picture showed the lady in brilliant white, astride a dolphin. Or Ginna thought it was a dolphin. It looked vaguely like a fish, and he had seen a fish before, swimming in a bottle being taken into Kaemen’s room. He was able to guess that the bright thing in the lady’s right hand was the sun. In the left was a tree.

He liked the lady of the second picture more than the other. He smiled at her. He pressed his hands together, as he had done so many times before, and opened them. A bubble of light floated up where the lady could see it. The girl had always seemed happy when he did that He hoped the lady would too.

* * * *

Just then the whole place was flooded with light. Someone had opened the door.

Ginna tumbled back and looked up at the most mountainous individual he had ever beheld, who peered down at him impassively from beneath a winged helmet He had a red moustache and a beard as big as a blanket

“Well, by The Goddess, what have we here?”

Ginna spoke a few of the words he knew, but the man didn’t seem to understand.

“You belong back upstairs, not down here.” The giant bent over to pick him up, and he stared, not sure whether to be afraid or not. To please the man he made a glowing ball which floated into his face.

The man recoiled before it touched him.

“Witchcraft!” he gasped, and backed away hurriedly.

Ginna had wondered many times before why no one else made lights in his presence, but he’d assumed they were too busy, or didn’t think him worth the bother. After all, they ignored him in every other way. It was the natural order of things, as far as he was concerned.

But now, for the first time, he understood that he was not like the others. Perhaps he was the only one who could do the thing.

Alone once more, he closed and opened his hands, and watched the light bubbles rise, then slowly drift to the floor. A draft from beneath the door made them roll in the air.

A while later he made his way back up the stairs. Fortunately the upper door was still open.

* * * *

Two years passed, and a serving woman came for him in his room and led him down those stairs again. It was an astonishing journey through many new corridors, and he caught glimpses of rooms vaster than any space he could imagine. There were pictures on the walls, often of the twin ladies, sometimes of men in winged helmets and armor, with battles going on in the background. He wanted to stop and look at everything, but 5ie woman dragged him on. Thick rugs lay underfoot in some stretches, muffling sound. For the most part the way was deserted. Twice he saw groups of wholly unfamiliar people going off on unimaginable errands.

The greatest wonder of all came when they emerged into an open courtyard beneath a bright blue sky. He had never seen the whole sky before, just pieces of it through small windows. He planted his feet firmly and refused to move until he had gazed more fully at this spectacle, but the woman slapped him on the ear, grabbed him under the arms, and carried him.

He was left in a new place, so distant from where he had been that he never saw anyone he had known before. He was among keepers of animals and workers of iron, and fascinated to watch both. The furnaces crackled merrily and were splendid if one kept a safe distance from them, and the animals were more so. Horses were mountains of flesh on legs, but huger still were creatures called katas, which stood on their hind legs twice as tall as any horse. They were hairless, greyskinned, with tiny forelimbs and even tinier seven-fingered hands, and small, narrow heads. He was never allowed near a kata, because they were rare and expensive and because one could smash him to mush with a flick of its tail, or so the keepers claimed. Where it joined the body, the tail was as thick as the man who warned him, and he was broad-shouldered. At the tip grew three spikes of white bone.

Ginna did not really know how to be a part of the society of stable hands and smiths. He didn’t know what to say. Their children played incomprehensible games. So he stayed out of the way and watched most of the time, learning, peeking out of corners until someone called him “The Mouse”. The name stuck.

He was better fed and clothed than before. Like everyone else he wore a simple tunic, and like the other children, he went barefoot.

He saw no one else making balls of light with their hands, so he thought it best to do this only in private. He did not like to draw attention to himself.

Eventually he made a friend. She was half a year older than he. Her name was Amaedig, which means Cast Aside. She did not seem to have any parents, but wandered from place to place as he did, sleeping wherever there was room. She was not good looking, and her back was slightly crooked, but he found her pleasant to be with. They played together among the metal scraps, and sometimes climbed atop something to watch the men feeding slices of meat to the Katas, or even trying to ride them in a small, fenced-off yard.

After a while he swore her into secrecy with as terrible an oath as he could think of (“If I tell this secret, I hope terror and doom will come upon me, and my arms and head fall off, and extra toes grow out of my empty neck!”), then took her into a closet and showed her how he made light balls.

“Can’t you do it?” he asked, as she gazed in amazement.

“No, but I wish I could.”

“Then try.”

She did. Nothing.

“How did you learn to do it?”

“I didn’t. I always could. I used to think everyone could, and then I thought maybe only grownups couldn’t, but now you can’t either. I don’t understand. Maybe I’m special.”

More spheres floated up, to the top of the closet. “They’re pretty,” she said.

* * * *

Ginna was seven when The Guardian first sent for him, and suddenly he was someone important. All faces were turned toward him. All hands helped as he was scrubbed and shorn and brought fresh clothing. All eyes looked after him as he was taken away and Amaedig ran up to him as he was leaving and said, “Will you come back? Will you?”

“I hope so,” was all he could say.

He came back. It was the first of many visits. Tharanodeth was in his declining years by then, and he sent for Ginna often. When the boy was still small he sat him on his knee and sang songs to him, or bade him sing other songs back. They traded riddles. The old Guardian even read to him from an ancient book, which from the date marked on its clasp had not been opened for fifty years. It told of the deeds of the remote forebears of the people of Ai Hanlo, how they had come out of the mountains and out of the desert to found the Holy City, which stood in the middle of a fertile plain in those days.

“It was a golden age,” said The Guardian of The Bones. “Men were content then, and the Earth was calm. It was before the death of The Goddess.”

“How did she die?”

“I don’t know, my boy. I don’t know. Does that surprise you? It has been prophesied that someone will find out, but all I can tell you is how it was discovered that she was dead. The age of peace ended. Suddenly all the world was in turmoil, even more than it is today. There were two suns in the sky and the land burned. Then winter lasted all the months of the year and it froze. The oceans froze too, but then they melted and rushed over the land. Invading hordes tore down cities mightier than our own. But this was not enough to let them know that The Goddess was dead. Pestilence, earthquake, and war had come before. No, it was discovered in this wise: a certain holy man, the holiest of all men living, who was sort of a guardian back before there were any bones to guard over, took a bone, an ordinary bone, the leg bone of one of his order who had died, and he wrote a message to The Goddess on it, begging for her help in the time of trouble. Then he cast the bone into a fire. The Bright Aspect of The Goddess could be made manifest through fire. But when he drew the bone out again, there were no cracks on it and the message was erased. No answers because there was no one to answer. By that he knew that The Goddess was dead.”

“But where did The Bones come from?”

“That, young man, is a holy mystery, which only I may know. I can’t tell even you. Now you are dismissed.”

Another year passed. The manner of the visits began to change. Ginna was brought in secret to The Guardian, and told not to speak of what went on. So he confided only in Amaedig.

It was during his eighth year that he was ushered into the private chambers of Tharanodeth and he found The Guardian dressed in heavy shoes and a travel cloak, with a staff in his hand.

“We are going somewhere,” the old man said. “We are going now, while I can still make the journey.”

Ginna’s heart leapt. So far in his life he had never been beyond the walls of the palace, and there was much within those walls he had never seen. Beyond the palace there was the lower city, beyond that—

He could not imagine what was beyond that. He had seen a little, but only from windows. It was very far away. So were the stars.

It was after midnight then, well into the stillest hours of the night Ginna no longer dressed in fine clothes to visit The Guardian, and he was in his usual plain tunic, and without shoes. He was not ready for any journey, but he went. Tharanodeth took him down a long, winding staircase, through a secret passage, until they had descended for so long he was sure they were at the center of the Earth.

The stone floor was intensely cold beneath his feet. Damp slime squished between his toes. Then the floor ended and there was only rough stone. He trod gingerly.

“Get up on my back,” said The Guardian. “I’ll carry you.”

He did, and the old man staggered and let out an “oompf!” but he carried him for miles. Once Tharanodeth looked up at the dripping stalactites and said, “We are no longer in the palace, but underneath the city itself.” Then the way sloped down sharply. “We are at the heart of the mountain,” he said. A long while afterwards, as they began to move up again, he said, “Now we are just barely in sight of Ai Hanlo. We are well beyond the walls.”

It was still dark when they emerged into the open air beneath the stars. The moon was bright and nearly full, and the old man pointed to the west, where it was nearing the horizon.

There stood a mountain revealed in the moonlight, surrounded by barren foothills and topped with crags and sheer cliffs. But all over the mountain, like ivy growing on it, were towers and walls, terrace after terrace of tiny houses, more walls ringed with towers from which pennons flew, and at the foot of the mountain still more levels of houses with a thicker wall encompassing the whole. Two huge gates were visible. Atop each tower, spread all the way up the mountain, watch-lights burned, and there were lanterns in many windows. The lights were a natural part of the city just as the city seemed a natural outgrowth of the mountain, and the sum of all seemed an enormous beast with glittering scales and a thousand eyes, crouching beneath the moon.

Tharanodeth set Ginna down, and bade him look for a long time. They stood there until the moon set.

“Now that you have seen the city of Ai Hanlo from the outside, as it sits upon Ai Hanlo Mountain, you will understand what I mean when I tell you that our ancestors did not build the city when they came here from far away. They carved its foundations out of the flesh of the stone.”

He pointed to the golden dome of the summit “Behold. That dome and the towers surrounding it comprise only that part of the palace which is visible from this side. And yet there is enough there for you to spend your whole lifetime exploring and even then you could not know it all in its fullness. And around the palace is the city, through which you could wander all your days, and still some of its ancient secrets would remain hidden. Yet consider how small they are seen from this distance. Just one mountain surrounded by hills, beyond which are wide plains and other lands. Now come. I want to show you something.”

He took the boy on his back again with difficulty. “You are supposed to be underweight. Have you gotten heavier without my permission?”

“No,” said Ginna meekly, too overwhelmed to be aware of the levity.

They traveled for hours over the sloping, rocky ground. Constantly Ginna looked back at the wonder of die city, and slowly, as he watched, the curvature of the terrain hid it from him. To be out of sight of Ai Hanlo was wholly incomprehensible, like being adrift between life and death. And yet there he was.

The eastern sky was reddening in front of them. In all directions nothing was visible except stones and scrubby underbrush.

Tharanodeth stopped and set Ginna down.

“Stand here and look,” he said. “Look, and you’ll see the Earth as it always was, even before the death of The Goddess. I come here sometimes to reflect, when the toils of my station are more than I can bear. I come out here to where it seems that mankind and all his works have made no more impression on the Earth than the passing shadow of a cloud. I tell myself not to worry, to face what I must face with courage and dignity, for nothing matters ultimately. I come out here to watch the sun rise.”

And they stood still as the glow in the sky increased and all the secret colors of the desert were revealed. Formerly dun brown hillsides suddenly flashed orange and crimson. There were furtive yellows and even a wink of blue. The colors and the long shadows cast by the stones shifted and flowed like a long, soft cloth being dragged across the land.

Ginna was sure he had never seen anything so beautiful.

“There is much more,” said The Guardian, and he took him on his back again.

It was well into the morning when they came to that ridge which had been a mere line on the horizon. As Tharanodeth made his way up the incline, one hand on his staff, the other behind the boy’s knee as he carried him, he turned his face from left to right and back.

There were mounds of crumbled stone all around them.

“You are in a city of ancient mankind,” he said.

“Where?”

“Here. In every direction. This is why we waited till dawn. At night the ghosts of the inhabitants would howl in our ears.”

Ginna did not know if he was joking or not.

When they topped the rise, Tharanodeth said between labored breaths, “And here is another city.”

Ginna got down, stared, and gasped.

All the way to the horizon, towers taller than any he had ever seen filled the land. They were hollow and broken off at the tops. Each had hundreds of empty windows. Sometimes slender bridges stretched between them. Sometimes these were broken halfway, and sometimes the towers themselves were little more than suggestions of shapes in heaps of rubble. And at the feet of them were shells of countless lesser buildings, all nearly buried beneath the talus of fallen masonry and sand. A few stranger shapes, taller than anything else, flickered over the city like shadows cast by a candle in a drafty tunnel, not substantial at all.

“It is one of the dead places,” the old man said. “I have heard that there are even larger ones elsewhere. This was a city as we cannot imagine a city, built by men we can scarcely think of as men. Surely The Goddess admired them. One legend has it that they created her, or some other one who came before her, to watch over the world after they were gone. No one can ever know what magic they possessed, or even what spells linger in a place like this. If you think our little mountain is vast, consider this. An immortal could spend all his days here and never examine it all.”

“But the people who built this? Where did they go?”

“I have taught you to read, Ginna, and I have a book I must show you sometime. It is by the philosopher Telechronos, who said that the ages of existence are like the times of the day. The cultures of the Dawn rose and built their cities, and those people imagined themselves to be all of history, and indeed they were in a way. But when their cities were as the mounds you have seen among the hills, when they moved no longer and their eyes were closed, then came the Morning, when works were mightier yet. In the brightness of Noon mankind climbed yet higher, attaining other realms and other worlds even. What you see before you is a city of the Afternoon, when the heights had been scaled and the spirit of man rested in the warmth of the sun.”

The boy was silent. He thought for a minute, puzzled. “But if this is so, where do we fit in?”

“Our place in the procession, the book says, is toward the end. We are creatures of the twilight. No more impression than the shadow of a cloud shall we leave behind, when both Ai Hanlo and this you see before you are dust. But while it stands, we can at least admire the corpse of something greater than ourselves. The spirit has passed from man, said Telechronos.”

“But what comes after us?”

“If there is another age, I think it will begin a whole new cycle. Perhaps there will be a place for mankind in it, perhaps not. I think even the laws and shapes of things, and the passing of time will be entirely different. In fact there is a curious prophecy—Telechronos himself made it when he lay dying. With his last breath he told of seeing a shining face looking down into his, saying that when at last one understands himself, the end will be the beginning and the beginning the end and the new age will open.”

Neither of them said a word as they returned to the city. Tharanodeth was too exhausted to carry him, so Ginna walked. He cut his feet on sharp stones but never complained. After a while the old man leaned on his shoulder. They rested often. After a long time, when both were faint from thirst and hunger, the towers of Ai Hanlo rose above the dry hills. It was nearly evening when they found their way into the tunnel, and the sun had set before they returned to The Guardian’s chamber. When they got there people were knocking on the outer door and ringing bells, calling out, “Dread Lord, Noble sovereign, urgent news. Pressing business.”

“It’s always urgent and pressing business,” sighed Tharanodeth. “Whenever I go away it piles up like water behind a dam.”

He let the boy out through a secret way, then went to face his courtiers. But just as he opened the door he fell down unconscious and they carried him to his bed, letting the affairs of state pile up even more.

* * * *

When he was twelve, Ginna saw Tharanodeth for the last time. The Guardian had not sent for him for several weeks, and he was disturbed by the silence. There was no message. But then The Guardian’s man came to him and nodded, and he knew how to go and where. He found the old man lying in his bed, and for the first time Tharanodeth seemed truly old to him. His long white beard seemed scraggly, no longer smooth and fine; his face was shrunken and pale; his bones were like a stark wooden frame over which a thin blanket of flesh had been draped.

Charms made from the skulls of men and animals hung from the bedposts. An intricately carven staff of polished ebony leaned against the wall where it could be easily reached.

The boy looked at the staff with dread. He knew what it was.

“Yes, it is for my last journey,” said Tharanodeth. “I have my walking shoes on, too.” He pulled up the blanket so Ginna could see them.

“Please... don’t...”

“Die? Please don’t die?” the Guardian laughed softly. Then he sighed. His breath was wheezing and tired. “I’m afraid none of us has much control over that, any more than we can prevent our epoch giving way to another. Telechronos said that He said it all, the old windbag. But listen to me, my friend. Yes, you are my friend. Guardians aren’t supposed to have friends. They can’t. Everybody wants something, or spies for this faction or is in the power of that lord. It is like a cave of spiders, each spinning webs to entrap the rest He who sits aloof, beyond all that, is the most alone. I have only you. You are the only one who is not tainted by intrigue. This is why I have tried to keep your comings and goings a secret. Of course a few people know. But they’ll keep quiet for a while yet, I hope.”

“But, why me?”

“There had to be someone. I think I would have gone mad without you. Some guardians have, you know, although their subjects interpret their madness as holy ecstasy. And why not you? You are mysterious enough to hold my interest Yes, very mysterious. I think there is more to you than the eye can see.”

“What? How am I so mysterious?”

“Who were your parents?”

Ginna was left speechless by the directness of the question. All he could utter was a babble of half-formed words. He sat down on a stool by the bedside and stared at his friend for a while in silence. All around him flickered scented candles, set there to attract the Bright Powers and drive off the Dark. Some sputtered. This and the old man’s dry breathing were the only sounds.

With a great heave The Guardian sat up, turned, and took the boy by the shoulders. He stared intently into his eyes.

“You didn’t have any parents,” he said. “You know that much already.”

“I was... found.”

“But do you know where?”

Ginna shook his head.

“In the same cradle with that horror of a son of mine. You didn’t know that, did you? Did you know that everyone said you were bewitched? My magician wanted you killed. He’s a fusty old buzzard, but he means well, so I think he really felt there was a danger to me. But I said no. I saw a destiny in you. I don’t know what. These things have a way of working themselves out. But something special.”

Exhausted at the strain of sitting up, he let go of the boy and dropped down onto his pillows.

Moved near to tears, wanting to open himself as fully to Tharanodeth as he had to him, Ginna did something he had never done before in The Guardian’s presence. He folded his hands together, then opened them, then folded them, until he had made a dozen balls of light and juggled them. They drifted slowly, none of them brighter than the candles. When he stopped they fell on the bed and the floor and winked out.

“Then it is true. You are magical.”

“I can do what you just saw. When I first came to you, I was afraid to. After that, I guess I never did.”

Tharanodeth smiled. “I never asked you to.”

“It’s as easy as talking or moving my fingers, but I don’t think there’s anyone else who can do it. I don’t know what it means.”

“I had really hoped you would,” said The Guardian, staring up at the ceiling, where the two aspects of The Goddess looked down on him. “I am going into a far country, from which I shall never return. They say that when we depart thence, when we walk the last long road, if we are brave and true and avoid all the perils, we come to paradise, and sit there listening to The Musician play beautiful songs for all of eternity. But this is uncertain, for no witness has ever come back to report it. I am afraid. I will tell you that much. I had hoped you could provide me with some insight, some comfort, some secret gained through your magical nature. Something. Have you ever had visions?”

Ginna spoke slowly, very carefully. “I have had dreams. You are usually in them. You are very wise and you lead me. Sometimes we walk in the dead city among the flickering towers, and I can see the faint outlines of the buildings as they looked when they were new. There are people hurrying back and forth. We try to talk to them, but they don’t stop. To them we’re invisible.”

“Then whatever secret is in you has not yet come out. Perhaps it shall when I am gone. That is why I fear for you.”

“For me?”

“Yes. If I could have things as I want them, you would be my heir and rule all of Randelcain6 after me. But I have made it clear from the start that you are not. I said so in front of witnesses when you were found, and for a very good reason. After I am dead, you must keep that quality which had endeared you to me. Stay out of politics. Don’t seek position or fame. Don’t get to know the right people. If you are part of even a little intrigue, a tiny stratagem, you are changed forever. Do you understand why I was so careful to disinherit you? If you had any claim to the throne, how long do you think you would be allowed to live? Kaemen has his followers already.”

“What shall I do, after—?”

“Just live. I hope you can do that. Then, if there is a destiny hovering about you, it will be fulfilled. If not, you’ll still be happier.” He took a ring from one of his fingers and gave it to Ginna. “Wear this always. It will tell people that anyone who harms you will face the curse of my ghost. It is my last command to you that you survive. See that it is carried out.”

“I love you,” the boy wept. He leaned over and put his head on the old man’s chest. He sobbed without restraint.

“I love you too.” Thin, pale fingers with skin dry as parchment stroked his hair. “I don’t believe guardians are supposed to love anyone. We’re supposed to be beyond all that”

Someone knocked on the door to the chamber.

“Holy Lord,” came a voice. “Are you awake?”

Ginna sat upright, stiff with terror.

“Go quickly,” whispered the old man. “It’s one of my accursed doctors. Very skilled, utterly useless now. A bore. You wouldn’t want to meet him.”

The boy left the bedside without another word. He drew aside a tapestry, pressed on a stone, and left the way he always did.

* * * *

Shortly before dawn, Ginna lay awake atop a heap of straw in his room in one of the short, squat towers overlooking the kata stables. The quiet of the night was broken only by the occasional snorts and whines of the beasts and the far off cries of the watch.

He chose to be alone then, but it occurred to him that most of the time he was alone anyway without any choice. Courtiers and soldiers ignored him as just another urchin. The stable folk, the trainers of the katas, the smiths, and the serving women were always polite. They tried to act naturally around him, as if he were no one special, but he knew, he could secretly sense that they were a little in awe of him and a little afraid. He sometimes overheard snatches of whispered conversations. He was, after all, so often led away by men of purpose and bearing. Someone was showing him more attention than he would normally merit, and trying to hide the fact He was, rumor had it, part of some intrigue, perhaps a child of high rank being hidden until some danger was past. But the gossipers could never possibly imagine the truth, that he was being summoned by The Guardian himself, that he was Tharanodeth’s friend.

His friend. It occurred to him that he had only two friends in the world. He knew so few people. He had been educated only by Tharanodeth, and spottily, learning whatever it had moved the old man’s fancy to teach him.

Tharanodeth and the girl Amaedig, whose name meant Cast Aside. And now Tharanodeth was dying. But he could weep no more. He had exhausted his supply of tears that evening, and there was only a hollow ache within him.

“Ginna.”

He sat up with a start. The straw rustled. He peered breathlessly into the gloom. The world was absolutely still. Something had shut out all the sounds of the night

“Ginna.”

“Here I am.” His heart pounded with bewilderment, then terror, then joy when he recognized the voice, followed by terror again. It was impossible that he was hearing that voice now, in this place.

“Ginna.”

Tharanodeth stood in the doorway to the room. He had the carven staff in his hand and he wore a travelling cloak and his walking shoes. His face shone brightly, as if a lantern were held up to it, and yet there was no lantern.

“Ginna, I am on the road now. It is a long way. Goodbye.”

“Wait! Where are you going? Don’t go!”

The light went out like a candle extinguished. The boy leapt up and stumbled out into the hallway which was filled only with the echoes of his shouting.

It was very dark every way he looked, and when he fell silent the night was still.

He walked the battlements until dawn in search of his friend, hoping for another glimpse, but he asked nothing of the few people he met. They couldn’t help him. He dared not tell them what he had seen.

The new day found him in a wide, high hall. The sun touched the blue glass of the skylight, flooding the room with color. On opposite walls were hung portraits for the bright and dark aspects of The Goddess. One, clothed in midnight, remained dark. The other, astride a dolphin, glowed with the brilliance of the sunrise.

Remembering when he had first met her, he placed his hands together, then parted them, and a ball of light rose up for The Goddess to see.

Suddenly trumpets sounded. Cymbals clashed. Many metal-shod feet tramped. Two huge doors swung wide in front of him, and suddenly the room was filled with people. First came the trumpeters, then a squadron of soldiers in full armor, with richly decorated shields and banners trailing from their spears. Drummers drummed. A line of boys Ginna’s age rang bells and chanted. Countless courtiers, lords, and ladies followed, all in their richest attire. In the midst of them was a chair on a platform, held aloft by eight burly men.

Ginna was so bedazzled by this intrusion that he just stood there in the middle of the floor, gaping.

“You there! Brat! Get out of here!” A captain in a scarlet cape and winged helmet came forward waving a sword.

“No. Let him stay. Let him be the first to congratulate me.”

Ginna looked up to see who had spoken. Everyone else looked up too. When that voice was raised, all others fell silent. He recognized the pudgy, pale figure on the platform, even though he had not seen him in years and certainly had never seen him like this, dressed in vestments which were black on one side and white on the other, and holding a golden staff in his hand.

It was Kaemen. He was only a month older than Ginna, but now he was the new Guardian, the holiest person in the world.

The great mass of people divided and flowed around Ginna like a stream around a boulder until the chair of Kaemen drew near him. Then the bearers set it down.

“Come forward,” said The Guardian, his girlish voice cracking in an attempt to be deep and commanding.

Ginna didn’t know what to do. Court etiquette was wholly strange to him. He had never spoken to a guardian in public before, or even with any noble lord.

He fell on his knees, keeping his eyes to the floor.

“You may kiss my hand,” said Kaemen. “Yes, Ginna, I know who you are. They say you are magical and were sent to bewitch me when I was a child.”

“Oh no! I wouldn’t—I could never do that—Dread Lord!”

“Of course you couldn’t. But you tried and you failed. Now it amuses me to see what you will do next”

“Holy One! I would never do anything. I didn’t! Please forgive me!” Ginna desperately hoped he had said the right things. Apparently he had.

“You may kiss my hand and look upon my face. Consider yourself greatly honored.”

Hastily he made one of the few court gestures he knew, that of Blessing Received, and to be sure he repeated it twice more. Then he raised his head, and took Kaemen’s sweaty, soft hand in his own and touched it to his lips.

The Guardian was doing his best to look on impassively, to demonstrate that this inferior did not concern him one way or the other, but he could not completely hide his astonishment when he noticed that Ginna wore Tharanodeth’s ring. And Ginna could not fail to see that flash of pure hatred on his face, even though he recovered almost at once.

Kaemen’s eyes were blue voids, revealing nothing.

The whole of the day and much of the evening were filled with the coronation of the new guardian and the funeral of the old. Countless rituals had to be observed, and officials, called Masters of the Act, oversaw each with scrupulous care. Kaemen alone was able to descend into a certain vault, while his attendants sang a hymn which could never be sung on any other occasion and were accompanied by instruments which could accompany no other song. He was the only one who could bring forth a certain reliquary containing a splinter of bone of The Goddess, and of all the living he alone among them was permitted to touch the inestimably holy corpse of his predecessor, to open the mouth, place the reliquary within, and close it again. This one act, with all its prayers, pauses at preordained stations, and pantomime re-enactments of the highlights of Tharanodeth’s reign, took hours.

Ginna was relieved that The Guardian let him go on his way after that first encounter. He watched the proceedings from a tree at the back of the crowd. The whole population of Ai Hanlo was present, this being the only time when the folk of the lower city were allowed within the forbidden precincts. He had never imagined there could be so many people alive in one place.

Tharanodeth lay on his bier with his travelling cloak wrapped about him, his death-staff in his hand, and his walking shoes on his feet. And yet Ginna knew that his friend had departed the previous night and was already well along his final, perhaps endless road.

He was left behind with his only remaining friend, Amaedig, and with Kaemen, who might be ignoring him for the moment, but had certainly not forgotten him.