Читать книгу Weirdbook #43 - Darrell Schweitzer - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

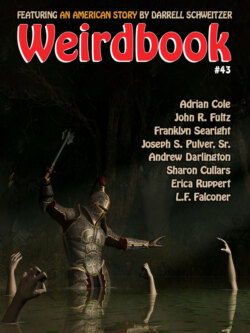

AN AMERICAN STORY, by Darrell Schweitzer

Оглавление“But I can’t tell an English club story,” I protested. “I’m an American.”

The circumstances were extraordinary enough that you might have thought that I could. Here I was, in this day and age, in one of those old-fashioned London gentlemen’s clubs of the sort most people think only exist in old books or BBC serials. I had travelled in Great Britain extensively, on both literary and business matters. I had many British friends. I had even made something of a hobby of British regional accents, which I could definitely hear, if not reproduce (nor would I insult my hosts by trying). In Yorkshire they speak in a distinct manner, in the Midlands quite another, in Devon, very differently, and none of these could be mistaken for the speech of London. Once, in Scotland, I had even asked a local about James Doohan’s accent on Star Trek and was told that 1) he was doing it very badly and 2) if Scotty were an engineer he would be an Edinburgh University man, and the first thing he would do would be lose that accent.

So I think it’s safe to say that I was that rare sort of American who understood just enough of British culture and ways to appreciate that the two societies are not the same, and that I had, just barely, glimpsed beneath the surface where tourists never see at all. It was enough to make me understand why I couldn’t tell a proper English club story. I couldn’t tell this audience what English life was about, when they knew more about every aspect of it than I did.

“Oh do go on, old chap!” my Brit friends said. They used such expressions as “Smashing!” and “Capital!” and “Jolly good!” which surely do not exist in living memory outside of a P.G. Wodehouse novel, and—here’s the important part—every last one of them rendered these phrases in a perfect imitation of a Hollywood fake English accent, which is not the same as an American snob’s fake English accent, or even an American theatre accent. That was when I realized I was helpless in the presence of ancient and inscrutable subtlety and cultivation, like a round-eyed barbarian surrounded by Chinese mandarins. These fellows could not only cross the divide between cultures, but turn around and look back from the other side.

They had me. I was after all, a guest. I despite my long acquaintance with some of them, I was only allowed in the club on the basis of a letter from my late father, and even then some will doubtless conclude that it was only two world wars and the loss of the empire which caused such a lowering of standards. But there I was, and as I sputtered and hesitated somebody pressed a fresh whiskey into my hand.

Right.

Blame the whiskey.

The fire in the fireplace burned low. Everyone leaned toward me attentively.

* * * *

You will have to excuse me for being vague about the geography and other details (I began), because I have this story second-hand at best. It happened to my father, before I was born. Now my late father, James Simpkins, was widely travelled, particularly in the company of his closest English friend, Frederick Darblethwaite—that’s not his real name, I hasten to add. Those two, I am sure, could have told many fine stories, and indeed my dad told me some of them, including, in confidence, the one I am about to relate now.

It seems that he and Freddy—that’s what he called him—were not only close pals—not mates, because an Englishman and an American can never really be “mates” in that sense—but colleagues during the Second World War. They engaged in top secret research and carried out certain missions, the nature of which I am not at liberty to divulge even now.

Let us just say that on a certain afternoon some while after the conclusion of the war, my dad was being driven in the pouring rain through what looked to him like very bleak English countryside, green enough to be sure, but grey with rain, a monotony of low, rolling hills, and little clusters of trees which doubtless have a name, a forester, and are recorded in the Domesday Book—one of the perceptions Americans have of England is that there is no empty, unused land there, any more than there are any serious distances—but I digress. It must have been weariness or the monotony of the ride which caused him to dose off.

He awoke to a thump, as the car’s wheel splashed in and out of a particularly large pothole as they passed through the narrow streets of one of those thatched-roofed villages which you only expect to see on National Geographic specials or on quaint postcards. He later learned the name of the place was—call it Nether Cheebleford. Where precisely it was, I suppose you could figure out on a map, but he didn’t and I haven’t.

Just before he reached the castle he fumbled about, because he had dropped the note he’d been holding in his hands onto the floor of the car. He found it, and glanced at it one more time before he put it in his pocket. It was a calling card which had been left at his hotel. There was a coat of arms on it, and a message scribbled on the reverse read:

Jim—

Come see me at once. I have something quite extraordinary to show you.

—Freddy.

The reason for the coat of arms, not to mention the perfectly maintained, ancient limousine which looked like it belonged in a museum, driven by a button-lipped, uniformed chauffeur who looked like he belonged in a museum, plus the castle which had been converted into a country-house sometime in the 18th century (“The best time to do it,” it was later explained) was that my father’s friend’s father had recently died and Freddy had inherited castle, grounds, limousine, chauffeur, coat of arms, and all. He was now Lord Cheebleford, and my dad—never mind all his long acquaintance with Englishmen, the safaris, and close cooperation during the war—by being on a first-name basis with an actual lord was definitely moving up in society.

The house was one of those establishments you think only exist on the BBC or in Wodehouse novels. There were servants lined up to greet him, a butler, several footmen, maids, the whole works. Then Freddy came bounding down the front stairs with something less than the customary English reserve, pumped my dad’s hand vigorously, and said, “How good of you to come! Splendid! Splendid! You must come see!”

Before my father was even settled in—the servants had made off with his luggage—Freddy, talking a mile a minute in a state of great agitation, conveyed him into the Conservatory, which was an ancient stone structure with a wall knocked out so it could expand out quite a distance onto the lawn into a series of greenhouses. It seemed that Freddy’s latest enthusiasm, in which with his newfound title and wealth he was fully able to indulge, was the collecting and raising of rare plants, particularly orchids. Now my father had only a passing interest in botany, and no particular fondness for flowers. In his generation, American men who liked flowers were either swishes or lounge lizards—although of course the English have always had their eccentrics, and that’s different. In any case Freddy was hardly the stereotypical orchid collector. You know: about four foot six, stoop-shouldered, ninety pounds, capable of speaking only in the tiniest, squeaky voice, and dominated by terrifying female relatives. Freddy was a tall, broad-shouldered man with a bristling, grey moustache. He had been a major during the war. His credentials as a scientist, of the wealthy, amateur variety, were impressive. He had been on expeditions. He had shot lions. He and my dad had saved each other’s lives a dozen times in tight situations. So if Freddy said a plant was worth seeing, if you will pardon the expression, it bloody well had to be.

It was too. At the far end of the greenhouses was a large, cleared area, in which had been placed a clay flowerpot the size of a small swimming pool. It was filled with earth, and there was a shovel handy, but nothing had been planted yet. There was something wrapped in a tarp, on a table nearby.

“I wanted you to see this before I put it in the ground,” said Freddy.

He unwrapped the tarp.

“My God!”

It was a bulb, or at least vegetable matter of some sort, about the size of a watermelon, ovoid, and covered with hairy tendrils or roots, which visibly writhed in the air. It may have been his imagination, but perhaps the thing even made a faint sound, like a teapot whistling in another room.

“Then you appreciate what this is,” said Freddy.

“Yes, I do.”

“It’s not totally without precedent, you know. There is a certain amount of literature on the subject.”

“But—Wells, Collier, Clarke—I thought that was all fiction.”

“Not entirely, old boy. Not entirely.”

“Where did you get it?”

All Freddy would say to this was, “We collectors of such things have connections. It’s an old system.” No more than that. There are some things the English will not reveal to foreigners, even if they happen to be close friends. It is the famous English reserve, you know.

As Freddy pulled on some quite ordinary gardening gloves and picked the thing up, fondly, gently, as if he were holding an infant—almost as if it were his own child, a thought my dad found decidedly disquieting—its tendrils reached up toward his face, but he pulled back before it could touch him.

My dad found it increasingly repulsive.

“It looks like it’s from outer space,” he said.

“It quite well could be,” said Freddy, and without further ado, he planted it, and then watered it with a watering can.

Some while later dinner was served in the great hall. One did dress for dinner. Freddy’s valet had laid out appropriate attire for my dad. They sat beneath rows of stuffed animal heads, many of which Freddy himself had shot; some of the others dated back to the late Middle Ages. There were suits of armor in the corners, shields and pole arms alternating with portraits of ancestors along the walls, and if a couple ghosts had tittered softly up in the dark above the heavy beams overhead, it would only have been appropriate. This was the kind of place where if there isn’t a ghost or two, you have the right to ask why not. Sitting there, my father realized, he could well have slipped back in time. This could have been 1900, or 1800, or even 1600, and if gentlemen in Tudor costumes accompanied by Queen Elizabeth the First had come thundering into the room, Dad might have been at a loss for the proper etiquette, but not wholly surprised.

The dinner was of course superb, and the evening very pleasant. They were the closest of friends. They reminisced for a while about their previous adventures. Lord Cheebleford—Freddy—inquired tactfully about my dad’s future plans, and when he said he expected to return to America soon and get married, Freddy congratulated him heartily. As for his own plans, Freddy expected to live here at Cheebleford Hall, as the place was called, cultivate plants and tenants (for in this part of England, the old sense of noblesse oblige was not a thing of the past) and take his father’s place in the House of Lords.

It seemed, my father began to suggest, that their adventuring days were over.

But Freddy’s attention was suddenly elsewhere. He was listening to something his guest couldn’t hear.

After dinner, they carried their drinks into the Conservatory. Freddy was all too eager to see how his prize plant was doing. My dad thought this a bit obsessive. How much could a plant have grown in just a few hours?

About five feet. When they got there, it had shot up several greenish yellow stalks in all directions, of a rather ghastly, unpleasant color somehow, but Freddy looked on the thing as if it were his darling and his treasure. He was even more interested in the bulbous area in the center, which had swelled into a mass like an artichoke waiting to open, only about three feet high.

Pale, greenish-white tendrils floated on the air, extending out from the artichoke.

My dad should have run screaming into the night at that point, and I am sure no one would have blamed him if he had, but he was no coward, Freddy was his close friend, and in any case Freddy didn’t seem the slightest bit alarmed.

Maybe it was just nerves. Delayed combat fatigue or something.

In fact, Freddy had become obsessed. In earlier times—1600 or so—they might have said he was bewitched.

By a plant.

In the days that followed, Freddy and my father went through the usual round of activities. They toured the countryside, visiting everything from Neolithic sites and Roman ruins to Norman churches, since my father was interested in that sort of thing. They called on the neighbors, who lived the castle across the valley, and even participated in a traditional fox hunt, for all my dad didn’t ride a horse very well and struggled to keep up. (“But I thought all you Americans were cowboys,” someone said. He reminded them that he was from Philadelphia. There are no cowboys in Philadelphia.)

But whenever he could, Freddy spent his time in the Conservatory, seated in front of the plant on a folding chair. Soon its bulbous center was over six feet tall. The tendrils could reach almost to the edge of the room. And there was no question that the plant was making noises, first whistling sounds, then something that sounded disturbingly like music, and finally like speech.

My dad tried to draw him away. He asked to be shown this or that local sight, and maybe he even came close to wearing out his welcome a couple times, but of course Freddy remained properly polite and accommodating. Sometimes, though, there was no help for it. Freddy was in the Conservatory with the plant, while my dad either wandered the grounds or sat in the library, looking for answers in some of the very curious volumes the lords of Cheebleford had accumulated over the centuries.

By the time he thought to take Blodgers, the butler, into his confidence and express his growing sense of alarm, it was too late.

The two of them discovered the inevitable result one morning, in the Conservatory. They found the folding chair, broken, and Freddy’s shoes, and the remains of his trousers, but that was all.

“Oh my God,” my father said. “We’ll have to call the police, or maybe the army, or MI5.”

“I don’t think that would be appropriate, Sir,” said Blodgers.

Dad looked at the plant with loathing. He reached for the shovel. “Well the least we can destroy the damned thing!” He swung the shovel into the field of waving tendrils, which caught hold of the shovel and yanked it out of his hands with surprising force and tossed it aside. Blodgers wrestled him away, into the corridor, well back among the more conventional greenery.

“Sir,” he said firmly. “You are a guest here, so I must ask you to observe certain proprieties. Nothing may be changed, much less destroyed, without the permission of Lord Cheebleford. His Lordship’s effects cannot be touched without specific instructions.”

“But your master has just been eaten by that goddamn cannibal plant—”

“Not, strictly speaking, ‘cannibal,’ Sir, I shouldn’t think, since it does not devour its own kind.”

“And you have time to worry about propriety, or even grammar.”

“More the correct vocabulary—”

“But your master has been eaten by the plant!”

“That is, admittedly, a bit awkward, Sir. He was unmarried, you see.”

“I know that!”

“That means he had no direct heir.”

“I know that!”

“Which means the ownership of the estate, and the preservation of Cheebleford Hall itself could be tied up in the courts for quite some time, during which time…where would the servants go?”

My dad stared at him in amazement. “Do you mean to tell me, that after your master has met what was no doubt a hideous fate, and all England, maybe even all the world may be in danger, you’re worried about your job?”

Very stiffly, he said, “There’s more to it than that, Sir. You Americans would not understand.”

And before my father could say anything more or do something desperate, the plant spoke up behind him.

“Very good, Blodgers. Quite right. You may go.”

In the few minutes while my father’s back was turned and he confronted Blodgers, the plant had grown perhaps another five or six feet, because now it towered over both of them. Dad turned back around and saw that the artichoke section was now at least ten feet tall and it was starting to open. At the top, inside a greenish-yellow, pulpy mass, was what was at least a startlingly realistic replica of the face of the late Frederick Darblethwaite, briefly Lord Cheebleford.

Maybe not so late.

It opened its eyes.

“Jim,” it said. “I know how this appears, but things are not quite what you think.”

“Really? What makes you say that?”

“If you will just come a bit closer, I will explain.”

Dad stepped closer, just a bit. The stalks rattled. The outermost tendrils brushed against his face. Instantly he hurled himself backwards.

“Oh, Jim, old chum, if only you were where I am now, it would be so much clearer. You would understand.”

“Well I don’t intend to be where you are,” he said. “Never.” He looked around for the shovel, but Blodgers, before leaving as instructed, had removed it.

That was the beginning of a tug-of-war of sorts, as my dad was before long just as bewitched or obsessed by the plant as his late friend had been. Because he was less and less sure his friend was entirely “late.” He got another folding chair and sat just outside of the reach of the tendrils, for hours, while the plant-thing tried to lure him closer. Blodgers, as long as the thing spoke with his master’s voice, considered it to be his master, and therefore took orders, saw to the running of the estate and the direction of the servants, and, to hear him tell it, all was placidly right with the world.

My dad listened endlessly, and spoke with the thing, as they went over old times and their old adventures. It knew all his jokes. It knew things he had confessed in intimate moments when they were such danger together that it seemed unlikely they would ever see another dawn. Even more strangely, it began to look more and more like Freddy. The face became clearer. Then as the artichoke-thing opened wider, the entire head emerged, and then his shoulders and upper body.

It was about that point that my dad had a very close call. He fell asleep in the chair, and while he slept the tendrils had grown even longer, wrapped themselves around the chair, and were ready to yank him into the thing’s gaping gullet, when he suddenly awoke and leapt free, and crashed into a table of potted plants, sending them spilling onto the floor. He lay half stunned and only slowly did he realize what the plant-thing that looked and spoke like Freddy was actually saying. It was repeating numbers, formulae, top secret stuff, the very things the two of them had worked on during the war, on which the security of the Free World now depended. So, for all he had yet another perfectly justified excuse to run screaming into the night in the conventional manner, it was his duty to stay here, for security reasons, to make sure that those secrets didn’t get out.

Shortly thereafter, the artichoke-like section opened all the way, and Freddy stepped free, onto the stone floor.

It wasn’t him, of course. It wasn’t human. It was green, and dripping, and comprised of fibers and leaves and tendrils, like one of those Renaissance paintings in which the human form is made up from fruits and vegetables, but it spoke with Freddy’s voice, and when Blodgers discovered it, he sent for the valet, and the two of them got the thing cleaned up, and touched up with a little makeup, and dressed in the proper clothes, and before long it could more or less pass, at least in a dim light, as Lord Cheebleford.

My dad had dinner with it on several occasions. There was a lot more meat on the menu than there had been previously. Freddy had been somewhat of a vegetarian, a preference he’d picked up in India. But now, it was meat and more meat, served almost raw. But he gradually came to look more human. The tendrils and fibers on his face blended together into something that looked more like skin, particularly if powdered with a bit of talc.

The tenor of the conversation changed. It was no longer about past adventures, or military secrets. Now, quite openly, the thing spoke of the trans-human condition, how, once he’d “passed over” Freddy had come to understand things from an entirely new and broader perspective. It spoke of conditions on other planets, and of vast intelligences which waited for us, out in space, and of the secrets soon to be revealed. It even conversed in alien languages, which no human ear had ever heard before, but which my father, perhaps more telepathically than through intellectual effort, was able to understand. He of all living men actually heard the haunting poetry of the Yh’ghai, which dwell on the outer three planets of star so far away it hasn’t even a name that you can find in astronomy books. There was much that I could not follow after that, as the tale was told to me, something about a mystical union of all intelligences in the cosmos and the awakening of a second “inner soul,” whatever that was, and so much more. I am sure that my dad would have been pulled in eventually, that he would have finally walked hand-in-hand into that Conservatory with the creature that had perhaps once been his friend Freddy, and confronted the plant-thing, and let it have its way with him. He knew his resistance was giving way. He could not escape. It was only a matter of time.

But, miraculously, he was saved, and the instrument of his deliverance was a telegram, from my future mother. It said simply:

WHY HAVEN’T I HEARD FROM YOU stop ARE YOU GOING TO MARRY ME OR NOT stop.

Dad could only show this to his host, who may have been a plant, but was still a gentleman. He said, “You’ve given her your word, haven’t you?”

“Yes, I have.”

“Well you can’t go back on your word. You’ll have to leave.”

So he left. He returned to America and married my mother, and a few years later produced me, the humble teller of this tale. He never returned to England for the rest of his life, though he told me much about it. He even confided some of the really strange things that he’d heard toward the end, though once he was out of the immediate proximity of Lord Cheebleford he could no longer call to mind a single word of the alien languages, or very much of what had been revealed. Yes, he made inquiries, and passed certain warnings through proper channels, and I when I got older could tell that he was on edge much of the time, and frustrated, very likely because he was not believed, or else there was some kind of conspiracy to cover up the truth. Despite this, we used to get Christmas cards from England, from Lord Cheebleford, and I even got some addressed to me, from “Uncle Freddy,” but I was not allowed to answer them, and my parents never answered theirs. Shortly before he died, Dad told me what he could, and I think what haunted him most was that, just before he left the estate, he had seen the plant one last time, and the artichoke section had blackened and collapsed in on itself, while the outer stalks had all quite definitely gone to seed.”

* * * *

Somebody started to laugh while sipping his drink and snorted.

There were a few polite murmurs as I finished my tale, and then the Club Skeptic tore into me.

“Now wait a minute,” he said. “What happened?”

“Apparently very little.”

“You would have us believe that sometime in the 1950s England was invaded by intelligent plants from outer space and nobody noticed?”

“Well there are certain accounts,” said another member. “Wyndham and all.”

“But those are fiction,” someone said.

“Yes, definitely, they are,” I put in. “It wasn’t like that at all.”

“Well then,” said the Skeptic, “how do you explain the incongruities between your account and the condition of Great Britain today? How do you account for it?”

Maybe this was where I made my fatal mistake. I paused, then held up my empty glass. The waiter filled it with whiskey. I took, not a sip, but a good stiff gulp. Yes, I think the whiskey was at fault. It clouded my judgment. It caused me to overestimate the value of my wit.

“Maybe there was nothing to explain,” I said. “Maybe my father got himself all worked up over nothing. This Freddy Darblethwaite inherited the estate and went through all the conventional motions as lord of the manor and lived out the kind of life expected of a member of his class, and he took his father’s seat in Parliament, and maybe one more vegetable in the House of Lords didn’t make any difference.”

I sat back, waiting to relish applause, but there was dead silence in the room. You could have heard a cliché drop.

And that was when I understood that I had gone too far, crossing some line of propriety that no American can ever cross. That was when I understood that I had been right to protest at the beginning, because I had no business trying to tell an English club story.

The rest of the evening passed with stiff politeness. There were other stories told. One elderly gentleman with white whiskers began, “When I was in In-jah, I was shooting tigers, until one of them shot back. Now that was a story,” and he told it, but I cannot remember the details, any more than I can recall what followed when another older member with a slightly Irish accent, who had clearly been awaiting his moment, began, “Ghosts? It is not so much a matter of what I believe but what I have seen.”

All the while the vast chasm between the condition of being American and that of being British gaped before me.

The whiskey clouded my mind. I fell asleep in the cab on the way back to my hotel.

I have been in the U.K. several times since. I have even spoken at conferences there, in the course of my business and literary career, but I have never had an opportunity to tell—or even hear—another English club story, because, unsurprisingly, they never invited me back.