Читать книгу Crossing The Gates of Alaska: - Dave Metz - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

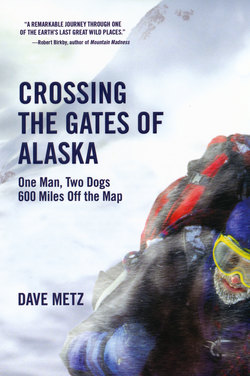

A LAND OF EPIC PROPORTIONS

ОглавлениеI’ve had a map of Alaska for years, displayed on my wall in epic proportions. It doesn’t simply display the names of towns and the length of rivers like most maps. It portrays the lowlands and the endless mountains in fine detail and vivid colors, starting with dark green at the lowest elevations where marshes, peat bogs, and woody forests lie, moving to yellow where the mountains begin to take shape, and finally golden brown where the peaks are highest. The Brooks Range is almost completely golden brown as it spans a thousand miles clear across the state horizontally like a corrugated barrier plopped down as if marking the end of the known world. To traverse the Brooks Range, you would have to follow the lay of the land and walk double that distance. The range is excessively wide and forms a subtle horseshoe shape with both east and west ends curving slightly farther north than the middle. Off the map, it’s really a world that shifts dangers with the extreme change in seasons, and you would have to be nearly insane to travel there in the dead of winter when biting wind and lung-blistering cold could kill you when your back is turned, and partly a fool to endure the height of the summer mosquito season. I stared at that map a lot, dreaming about the wilds of Alaska and when I was planning my trek across the range.

Only a handful of people are known to have traversed the entire length of the Brooks Range. Most made the trek from east to west. Only a small fraction made the trek in one unbroken push, and even less did it completely on foot. Of all the reading I’ve done about journeys there, no one traveled the exact route I planned to take. I didn’t choose my route because it had never been done before—it may have for all I know. I chose my route because it looked like one of the best ways to connect with villages where I could get food. I couldn’t afford a lot of charter planes flying me in food drops. I had to mail my food to villages along the way. I also picked the town of Kotzebue, Alaska, to start; it had a fairly large airport for the size of town it was, where I wouldn’t have to connect to a smaller, plane in Anchorage or Fairbanks. I could fly an Alaska Airline jet all the way from Portland, Oregon, to Kotzebue. This meant I didn’t have to spend time waiting for connecting flights that would expose my dogs to cold and unfamiliar surroundings longer than necessary.

Curious, I searched the Internet to find out who had traversed the entire range. Dick Griffith had the first documented crossing from 1959 to 1979 traveling west from the village of Kaktovik to Kotzebue by foot, raft, and kayak. Roman Dial was the first person to complete the traverse in one season, traveling from Kaktovik to Kotzebue in 1986 by skis, foot, pack raft, and kayak. He made another partial traverse in 2006, incredibly traveling east from Kivalina to the Dalton Highway in just under twenty-three days. Keith Nyitray, who appeared in the April 1993 issue of National Geographic, made the first continuous trek of the entire range, starting from Fort McPherson in the Northwest Territories, Canada, heading west to Kotzebue. He made the journey in about ten months by dogsled, foot, snowshoe, raft, and canoe. He nearly starved to death on the Noatak River and endured a couple of months without seeing another person. I read that article at least a dozen times and oft en left it on my nightstand to thumb through before I went to sleep. I considered Nyitray’s feat the greatest land traverse I had ever heard about. A foot traverse across the Brooks Range lacks the glamour of an expedition to the North Pole or a shot across Greenland because you can’t travel nearly as far and there isn’t really the danger of crossing vast reaches of ice. But the rainbow of colors on my map alone told me the rough and changing terrain could stop an army in its tracks. For a man alone, it could make him break down in despair. You’re also not likely to get much notoriety when you’re finished. When you’re done you will have to return to the niche in society you came from and it’s likely not too many people will give your accomplishment much of a glance. I didn’t care too much about that. The Brooks Range was the best frontier I could find, the best place to lose myself.

There were a few more remarkable crossings of the Brooks Range. I thought all of them were nearly impossible. Never did I think I would make it across the entire range in one season, mainly because I knew I was going to have to travel farther between food drops, which meant I would have to carry a larger load and travel slower than if I could have set up a dozen or so drops. There are only a few villages in the Brooks Range where I could mail food to, so I knew my pack was going to weigh close to a hundred pounds at some points, but I went into my journey with the single goal of remaining in wilderness for a few months. I needed some sort of goal to be able to stick it out for more than a couple of weeks. I added the trek so that I would have somewhere to walk toward, a sort of end point to reach, which I didn’t really care if I made it to or not. I simply wanted to reach the mountains and learn something about nature and myself. But I planned my trek out thoroughly over a thousand miles across the entire state, just in case the miles rolled by and I found myself doing better than I expected.

I prepared a long time to cross the Brooks Range and the Gates of the Arctic National Park, though most of the time I never realized specifically the long trek I would endure. From as young as ten when I learned that such a place like Alaska still existed in the world, I always had my sights set on it in some way, where rural woods were only a minute fraction of what true wilderness was supposed to be like. I wanted to be good at every aspect of moving through nature. I wanted to be able to sprint through the forest quickly and to run for long distances. I wanted to be flexible, strong, and able to climb trees like a gibbon, and most important, I wanted to develop a phantomlike sense of direction so I could never get lost.

I must have traveled to Alaska about a dozen times from the time I was eighteen until I began my trek. The land acted like a magnet on me and I couldn’t stay away. My first trip was when I was eighteen. I drove up to Denali National Park with a mutual friend of my grand-father’s. His plan was to drive up and learn how to become a bush pilot. My plan was to hitch a ride with him until I found a suitable place to step off the highway with my backpack and disappear into the backcountry. Well, I did that in Denali, and the reality of the land sank into me. It was mainly the immensity of Alaska and the absolute lack of people that struck me. I was instantly hooked on the place, but I wasn’t mentally ready to travel the land yet. There was no place to get more food if I ran out, and no one to help me if I were to get into trouble. The first night alone I was scared, camping in grizzly bear country without any protection at all. I didn’t really understand bears then, so it made my trip unnerving. I kept expecting some raging monster to rip through the wall of my tent and tear me to pieces. I didn’t understand that bears weren’t nearly as dangerous as I had been convinced, and that my hardwired primate brain amplified fears that were only mildly warranted, especially at night, especially alone. Satisfied that I had seen enough to realize that Alaska was the place where I wanted to come back to, I left a few days later and flew home to Oregon with my last $300 in the world. The enchantment of the last frontier had been permanently implanted within me, deeper than I could have imagined.

I conditioned myself to hike off trail, mainly because I always liked slipping through the foliage to get close to the copiousness of nature. And I always knew one day I would be going to some exotic wilderness still smoldering somewhere on the planet where humans had not yet slashed trails or roads across its fertile turf. I wanted to be ready. When I wasn’t traipsing off trail in the woods somewhere, I was training fanatically: running, cycling, lifting weights, or climbing trees. I love working out. Sometimes I would lift logs in the woods when I wasn’t near a weight room. I think most of the people who traversed the Brooks Range were athletic much of their lives. I can’t imagine anyone just one day deciding to go for an extended trek there without having some sort of a physical fitness base and the mental strength that comes after it. Sometimes I had doubts about why I was doing all those things and spending so much time in the woods. But I never once accepted that I could do without wilderness, even when I was a child.

It wasn’t until I was about thirty that my specific preparation for trekking across the Brooks Range took shape. I scanned a lot of maps over several years, always searching for the most efficient route. I pored over highly detailed maps, mile by mile, until I had a navigable route plotted out all the way across the state. I not only chose my route out of convenience, but also by picking the areas I liked the most. The route I finally mapped out for my 2007 adventure was mostly unique. I would be heading from west to east unlike most other adventurers whom I had read about who had traversed from east to west. I wouldn’t be floating any major rivers, either. Adventurers who travel east to west have the time-saving luxury of floating a couple hundred miles on either the Noatak River or the Kobuk River when they are thin and aching for the finish.

I wanted to spend much of my time in the taiga forests south of the Brooks Range crest. I craved those woody areas of the globe. My plan was to start in the village of Kotzebue on the northwest coast of Alaska in late March. I had to start that time of year when the weather was brutally cold so I could ski up the Kobuk River towing a sled. I had to start when the water along the coast was still frozen so I could cross it. Skiing part of the way would seem like a more rounded adventure and a great way to get in better shape before the torturous days of hiking began to beat me down. It would be faster to ski on a major river than it would be to hike across barren woodland, especially with the dogs helping me pull my gear. I could travel critical distance early in the season before the snow melted. To cross all of Alaska on foot in one season, I most likely would have to ski, snowshoe, or dogsled part of it. I didn’t want to float any rivers for a great distance. It seemed like cheating to me, not a pure on-foot adventure like I wanted.

I could have chosen the Noatak River to ski on, but it’s farther north where there are no trees, and where the weather is more severe. And there aren’t any villages along the Noatak once it gets away from the coast. I thought the Kobuk River would be a safer route and contain more forest cover. It would feel more like home to me while I was exploring that far-reaching land.

After the Kobuk River I planned to get more supplies in the village of Ambler, and I would then turn northeast up the Ambler River. I had to reach the headwaters of the Ambler River past all gnarled trees before the river thawed and broke apart in late April. At the headwaters I planned to begin hiking. It would be the point where I could begin traveling light and fast. Well, I hoped so anyway, but no one can ever be totally prepared for the harsh, uneven ground of Alaska.

Next I would hike over Nakmaktuak Pass to the Noatak River and cross it. Then I would head up Midas Creek and continue east on the Nigu River until I joined up with the Killik River. I would walk down the Killik for a few days and turn right onto Easter Creek, following it for several days until I hit the John River. Then I would follow the John into the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, where I was scheduled to meet Julie, my brothers Steve and Mike, my nephew Aaron, and two other friends. Then we would all hike to the village of Wiseman on the Dalton Highway together.

Trekking from Ambler to Anaktuvuk Pass was about 300 miles across some of the remotest country in the state, and the world. I could expect to be alone the entire time. I couldn’t find anything specific about people hiking all the way across that region, just general information about backpacking in Alaska and about the hardcore adventurers who had traversed the entire state. When most people go backpacking or hunting in the Brooks Range, like most of Alaska’s backcountry, they hire a private plane to fly them in and pick them up when they’re done. The distances are just too daunting. But I wasn’t going to do that. I was going to walk in from about as far away as I could get. In the Gates of the Arctic I knew I would be crossing an unknown, blurry void where I didn’t know the terrain. I had to study the maps to find a way through for myself. There were no guide books and no one was going to show me the way.

The Dalton Highway would be the likely end point of my journey, but in the back of my mind I hoped somehow I would make incredible time so I could continue east toward Arctic Village. Then I would proceed to the Canadian border. But that would be an epic feat and I was pretty sure I would be a bag of bones by the time I reached Anaktuvuk Pass. I concentrated on the first half of Alaska, from Kotzebue to the Dalton Highway. I knew that distance would take at least three months.

Three months before my departure, I spent hours a day at Julie’s house studying my maps, searching for the best gear on the Internet and loading food and gear into my boxes out in her garage. I got my journals ready and planned to log my miles as an estimate, following the curves of the river valleys. I had practiced using a GPS (global positioning system that uses satellites to pinpoint your location) unit and a compass before, which I would be bringing, so navigating would be more automatic when I got out there.

The first boxes I had were the largest and contained the most gear. I had to send items that I needed for coping with extreme cold and ice. One of the boxes I would send to Kotzebue had nothing but clothes. I found most of my clothes over a period of about six months. I always thought it was silly to spend a lot of money on clothes. Some high-tech gear is overrated and way overpriced. I found thick wool socks for a dollar a pair from an outdoors store in Portland. I found some expedition-weight bib pants there, too, to wear under my wind pants. I found a pile jacket, with a raised collar (critical for cold weather), from the Goodwill store in Corvallis, and several sweaters from the Salvation Army store in Roseburg for about three dollars apiece. Except for a T-shirt that I would wear in June, none of my clothes were made of cotton. They were either wool or some other synthetic fiber that wouldn’t absorb too much moisture. I bought only a few items brand new specifically for this trip. The rest I scrounged up from friends, borrowed, or bought at secondhand stores. One new item was a four-season tent, and another a pair of ski boots. I knew I needed the best boots I could find to keep my toes from freezing. The toes are always the first part of the body to fail in freezing temperature. They’re small and so far from the vital core of the body. I had to devote extra care to my feet. My boots were heavy-duty backcountry boots, with a thick insulated lining and a hard, outer plastic shell to keep out even the tiniest draft. Where you have to start out each morning from a tent in icy Alaska cold, you can never have boots that are too warm.

My brother Mike gave me two pairs of skis for my trip. One pair would be a backup. They were basically older style telemark skis, with a free heel so I could simulate walking. The skis were wide enough so I could manage the uneven snow surface without losing my balance, but still narrow and lightweight enough so I could make good time. Your ankles tend to bend over sideways on skis that are too thin, so you have to find the right width. On perfect flat snow I could use really narrow skis to make good time, but I would never find ideal conditions where I was going.

I had to be creative with my food since it would take up most of the weight. I packed a lot of lentil beans in bulk and stayed away from too many freeze-dried dinners. They’re ludicrously expensive, plus the packaging material would weigh too much on a trek where each saved ounce was precious. I had to be able to carry a month’s worth of food on my back once I started the hiking part of my journey, and the dogs had to carry about twenty-five pounds each in their packs. The main staple foods I packed were lentil beans, oats, large blocks of cheese, noodles, cocoa, coffee, powdered milk, and piles of snack food. I also packed toilet paper, matches, maps for the next leg of the journey, and mosquito repellent and sunblock on the later sections when the weather warmed up. I also packed toothpaste, dental floss, fishing line for fishing and for sewing up my clothes, and an extra shirt and hiking pants for the later sections.

As much as I stared at maps and prepared, I knew it would never be enough. The land looked immense even on my colorful wall map where instead of using two fingers, I had to use two hands to measure the distance between points. And there weren’t many names of the land features, mainly wide blank spaces of drawn-in creases and folds in the mountains and varying degrees of extravagant color. I would be hiking through regions where no modern human had ever traveled and likely would come across obstacles that I would have to go around to get by, and in the process lose valuable time and energy. And there were going to be the countless miles of indestructible mounds of grass called tussocks to slow me down and frustrate me like nothing else. I knew I would face excruciating loneliness and hours of physical exertion. I planned to take a shotgun with me, but I hoped to avoid violent confrontations with large animals. I would bring it just in case so I could sleep better at night. I worried about moose or wolves attacking my dogs, and of course some of the largest bears on the planet. To prepare for them, I figured I needed to know how to get along with them and stay out of their way. Everywhere else was mine for wandering. My eyes glimmered with joy when I came upon so much wild emptiness on such a small map. I knew the more uncharted space I saw on my wall map, the more there would actually be ahead when I got on the ground. I couldn’t wait.